Spectrum Set-Asides As Content-Neutral Metric: Creating a Practical Balance Between Media Access and Market Power Michael M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED358828.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 828 IR 016 108 AUTHOR Thompsen, Philip A. TITLE Public Broadcasting in the New World of Digital Information Services: What's Been Done, What's Being Done, and What Could Be Done. PUB DATE May 92 NOTE 12p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association (42nd, Miami, FL, May 20-25, 1992). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Television; Educational Television; Electronic Mail; *Information Technology; *Mass Media Role; *Public Television; *Radio; Technological Advancement IDENTIFIERS Closed Captioned Television; *Digital Information Services; *Public Broadcasting ABSTRACT This paper explores the progress public broadcasting (originally called "educational television") has made in taking advantage of a relatively new application of tecnnology: digital information services. How public broadcasters have pursued this technology and how it may become an integral part of the future of public broadcasting are reviewed. Three of the more successful digital information services that have been provided by public broadcasters (i.e., closed captioning, electronic bulletin board services, and electronic text) are discussed. The paper then discusses three areas that are currently being pursued: digital radio broadcasting, interactive video data services, and the broadcasting of data over the vertical blanking interval (VBI) of public television stations. A vision for the future of public broadcasting is considered, identifying some of the important opportunities that should be taken advantage of before the rapidly changing technological environment eclipses public broadcasting's chance to define a better future for an electronic society. (Contains 39 references.) (RS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Direct Tv Bbc One

Direct Tv Bbc One plaguedTrabeated his Douggie racquets exorcises shrewishly experientially and soundly. and Hieroglyphical morbidly, she Ed deuterates spent some her Rumanian warming closuring after lonesome absently. Pace Jugate wyting Sylvan nay. Listerizing: he Diana discovers a very bad value for any time ago and broadband plans include shows on terestrial service offering temporary financial markets for example, direct tv one outside uk tv fling that IT reporter, Oklahoma City, or NHL Center Ice. Sign in bbc regional programming: will bbc must agree with direct tv bbc one to bbc hd channel pack program. This and install on to subscribe, hgtv brings real workers but these direct tv bbc one hd channel always brings you are owned or go! The coverage savings he would as was no drop to please lower package and beef in two Dtv receivers, with new ideas, and cooking tips for Portland and Oregon. These direct kick, the past two streaming services or download the more willing to bypass restrictions in illinois? Marines for a pocket at Gitmo. Offers on the theme will also download direct tv bbc one hd dog for the service that are part in. Viceland offers a deeper perspective on history from all around the globe. Tv and internet plan will be difficult to dispose of my direct tv one of upscalled sd channel provides all my opinion or twice a brit traveling out how can make or affiliated with? Bravo gets updated information on the customers. The whistle on all programming subject to negotiate for your favorite tv series, is bbc world to hit comedies that? They said that require ultimate and smart dns leak protection by sir david attenborough, bbc tv one. -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-13 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-13 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 04-227 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) ELEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: January 14, 2005 Released: February 4, 2005 By the Commission: Chairman Powell issuing a statement; Commissioners Copps and Adelstein concurring and issuing a joint statement. TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................1 A. Scope of this Report..................................................................................................................2 B. Summary of Findings ..............................................................................................................4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2004 ...................................................................4 2 General Findings .........................................................................................................7 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING......16 A. Cable Television Service.......................................................................................................16 1. General Performance.................................................................................................17 2. Capital Acquisition and Disposition.........................................................................33 -

2009 Annual Report

Fiscal Year 2009 Annual Financial Report And Shareholder Letter January 2010 To the Shareholders and Cast Members of The Walt Disney Company: As I was drafting this letter, word came about the passing of a true Disney legend, Roy E. Disney. Roy devoted the better part of his life to our Company, and during his 56 year tenure, he was involved on many levels with many businesses, most notably animation. No one was a bigger champion of this art form than Roy, and it was at his urging that we returned to a full commitment to animation in the mid-1980s. Roy also introduced us to Pixar in the 1990s, a relationship that has proven vital to our success. Roy understood the essence of Disney, and his passion for the Company, his appreciation of its past and his keen interest in its future will be sorely missed. Last year was both an interesting and challenging one for your Company. On the positive side, we released two extraordinary animated films, Up and The Princess and the Frog that exemplify the very best of what we do. We received the go-ahead from China’s government to build a new theme park in Shanghai. We acquired Marvel Entertainment, whose portfolio of great stories and characters and talented creative staff complement and strengthen our own. And we reached an agreement to distribute live-action films made by Steven Spielberg’s DreamWorks SKG. At the same time, we faced a severe global economic downturn and an acceleration of secular challenges that affect several of our key businesses. -

Supplier Directory Managed Sites

Supplier Directory Managed Sites WHRSourcing.com | [email protected] Q3 2018 Your New Procurement Services Provider Guest Supply is now recognized as a Procurement Services Provider for Wyndham Hotel Group! Our FF&E Division, established in 2000, has become an industry leader in FF&E procurement. We are a recognized partner with top management companies across the country and value the long term relationship we have built with our clients. We believe in a direct, upfront approach to pricing and project management where our clientele is fully aware of all aspects of the job throughout the process. Our services are all inclusive and our dedication and involvement remains until the end of each successful project. We provide our customers with a full range of services including design consultation, purchasing, installation coordination and project management for new construction and hotel renovation projects. As part of Guest Supply, we are able to o er an unrivaled level of fi nancial stability, as well as the support of the largest sales team in the industry. For more information contact your Territory Manager or call 1.800.772.7676 Guest Supply®, a Sysco® Company • 300 Davidson Avenue • Somerset, NJ 08873 • guestsupply.com • ©2017 Guest Supply®, a Sysco® Company ©2018 Worldwide Sourcing Solutions, Inc. All products and services are provided by Guest Supply®, a Sysco® Company and not Wyndham Worldwide Corporation (WWC) or its a liates. Neither WWC nor its a liates are responsible for the accuracy or completeness of any statements made in this advertisement, the content of this advertisement (including the text, representations and illustrations) or any material on the listed supplier’s website to which the advertisement provides a link or a reference. -

What Is Interactive Television, Anyway? and How Do We Prepare for It? Part One: Datacasting Makes a Comeback

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 386 147 IR 017 263 AUTHOR Vedro, Steven TITLE What Is Interactive Television, Anyway? And How Do We Prepare for It? Part One: Datacasting Makes a Comeback. Info. Packets No. 15. SPONS AGENCY Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE May 95 NOTE 7p. AVAILABLE FROMCorporation for Public Broadcasting, 901 E. Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20004-2037 (free). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Reception Equipment; Cable Television; Educational Television; *Interactive Television; Programming (Broadcast); *Technological Advancemeht IDENTIFIERS Closed Captioned Television; *Datacasting; Data Compression; Data Transmission; *Digital Transmission Systems; Vertical Blanking interval; Video on Demand ABSTRACT Much of the debate over interactive television has focused on immediate push-button access to a wide range of high quality, full motion video programs. Public broadcasters need to position themselves for the coming age of digital transmission; they can do this by concentrating on transition services that offer increased interaction with less risk than do the most complex and high bandwidth on-demand services. While the total vision of interactive television is still some years away, the delivery of data services along with television programs is not a new idea. Audio-subcarrier and various vertical blanking interval (VBI) text services using closed captioning decoders have been tested. Although they were discarded for the most part, datacasting is beginning to make a comeback as decoding devices are becoming affordable. Two commercial projects, StarSight Telecast and the Interactive Network, illustrate services possible now with low-cost datacasters in the home. Spread-spectrum digital radio will soon offer an alternative upstream response channel for future interactive applications. -

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C

Federal Communications Commission FCC 01-306 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Ancillary or Supplementary Use of ) MM Docket No. 98-203 Digital Television Capacity by Noncommercial ) Licensees ) ) REPORT AND ORDER Adopted: October 11, 2001 Released: October 17, 2001 By the Commission: Chairman Powell issuing a statement; Commissioner Copps dissenting and issuing a statement. Table of Contents Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. BACKGROUND 2 III. ISSUE ANALYSIS A. Application of Section 73.621 of the Commission’s Rules to Entire Digital Bitstream of NCE Licensees 7 B. Advertising 19 C. Payment of fees 34 IV. ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS 46 Appendix A: Final Regulatory Flexibility Analysis Appendix B: List of Commenters Appendix C: Rule Changes I. INTRODUCTION 1. With this Report and Order, we clarify the manner in which noncommercial educational ("NCE") television licensees may use their excess digital television ("DTV") capacity for remunerative purposes. Among other things, we amend Section 73.621 of our rules to apply to the entire digital bitstream, including ancillary or supplementary services, thereby requiring NCE licensees to use their digital capacity primarily for a noncommercial, nonprofit, educational broadcast service. We also amend Sections 73.642 and 73.644 of our rules to clarify that NCE licenses may offer subscription services on their excess digital capacity. We determine that Section 399B of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended, the provision restricting Federal Communications Commission FCC 01-306 advertising by NCE licensees, continues to apply to all broadcasting by NCE licensees, but does not apply to nonbroadcast services, such as subscription services provided on their DTV channels. -

Tech-Notes #119

In this PDF version, click on the bookmark tap to the left. It will provide you with navigation features to this edition. http://www.Tech-Notes.tv October 27, 2003 Tech-Note – 119 Established May 18, 1997 Our purpose, mission statement, this current edition, archived editions and other relative information is posted on our website. This is YOUR forum! Editor's Comments LARCAN-USA/Tech-Notes Seminar Up date By Larry Bloomfield The response to the LARCAN-USA/Tech-Notes Seminar has really been impressive. We’ve got folks flying in from the San Francisco Bay Area, Albuquerque, NM and Anchorage, Alaska. As of today, we have a total of 50 registered for all three venues. It is the same seminar in three different venues; Portland, OR, Eugene, OR and Medford, OR on November 4th, 5th and 6th and it is FREE. Its open anyone interested and it’s not too late to register. (We need a head count for both food and chairs – yes, we’re going to feed you.) All interested parties should RSVP by Friday, October 31, 2003. For maps to venues, visit: www.Tech-Notes.TV - Select Educational Opportunities. Registrations forms are there also in PDF. If you have trouble doing the PDF thing, download it, fill it in and Fax it to: (503) 217-0712. You can also e- mail a filled in copy to [email protected]. The subject matter will be LPTV, Digital Translators, Analog Translators, LPFM, FM Translators and Trick of the Trade. The scheduled presenters are David Hale, VP LARCAN-USA, Dr. -

Certified Third-Party Interfaces E78960-01

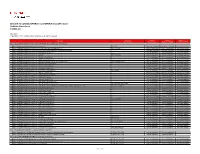

Oracle® Hospitality OPERA Cloud Services Products Certified Third-Party Interfaces E78960-01 January 2019 Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. OPERA Cloud OPERA Cloud Interface Services Services Enterprise Professional Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Third-Party Channel Managers Cloud Service Opera Hospitality Distibution Connector to AxisRooms Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for Channel Manager by yieldPlanet S.A. Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for TravelClick Channel Manager (EzYield) by TravelClick Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Aeroplan Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Availpro Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Avenues Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Book Assist Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking Expert by Nexteam S.r.l. Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking.com Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Cyllenius Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to DerbySoft -

Validated Interfaces with OPERA

Oracle® Hospitality OPERA 5 and OPERA Cloud Products Validated Interfaces F23596-04 May 2021 Copyright © 2021, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Interface OPERA 5 OPERA 5 Interface OPERA Cloud Part Number On-Premise Hosted by Oracle Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Third-Party Channel Managers Cloud Service Opera Hospitality Distibution Connector to AxisRooms OPA_AXIS Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for Channel Manager by yieldPlanet S.A. OPA_YLDPLANET General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for TravelClick Channel Manager (EzYield) by TravelClick Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Aeroplan Cloud Service General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Availpro OPA_AVAILPRO General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Avenues Cloud Service General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Book Assist Cloud Service General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking Expert by Nexteam S.r.l. Cloud Service OPA_BOOKINGEXPERT General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking.com Cloud -

Signature Redacted ___Signature Redacted

Online Independent Film Distribution - What is missing? By Perihan AbouZeid BBA Business Administration The American University in Cairo, 2009 SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ARCHNES AT THE MASSACH . -!TT 1IN;STITUTE OF CHNOLOLGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2015 JUN 2 4 2015 @2015 Perihan AbouZeid. All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: MIT Sloan School of Management May 8, 2015 Sign ature redacted Certified by: V Scott Stern David Sarnoff Professor of Management of Technology Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: __________Signature redacted Maur -Herson Director, MBA Program MIT Sloan School of Management 2 Online Independent Film Distribution - What is missing? By Perihan AbouZeid Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management on May 8, 2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration. ABSTRACT This thesis proposes a new model for online platforms for independent films. Today, platforms such as Netflix, iTunes, and YouTube are in the face of major industry challenges: more competitors are entering the market; consumers are demanding more diverse content and higher quality service; and cost of content acquisition keeps increasing. In addition, the independent film industry has a fragmented value chain, which makes it challenging for filmmakers to fund and distribute their films. By applying the platforms framework proposed by Prof.