Rambling in Palestine by Carey Davies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2014 Newslette – Summer

Newsletter August 2014 Israel's leading Tour Operator since 1976 with you all the way! SUMMER 2014 IN ISRAEL SUMMER 2014 IN ISRAEL ”לא יִשָּׁ מַעעֹוד חָמָס בְּאַרְצֵךְ דשֹׁ וָשֶׁ בֶר בִּגְבּולָיִךְ וְקָרָאת יְׁשּועָה חֹומתַיִךְּושְׁ עָרַיִךְ תְּהִלָּה” ”Violence shall no longer be heard in your land, neither robbery nor destruction within your borders, and you shall call salvation your walls and your gates praise.” Isaiah, Chapter 60, Verse 18 Back to Routine As September rolls in and summer fades, Amiel Tours, your Israel destination expert, is coming back better than ever! We have created this special newsletter just for you! Please scroll down and see the many attractions Israel has to offer! עם אחד בלב אחד ONE Nation ONE Heart SOLIDARITY MISSION TO ISRAEL September 8-13, 2014 Please join us in Israel and share the optimism and vision of the Israeli people with us as we stand united. This mission guarantees you an insight into the daily life and reality of living in the South under constant threat. ”THINGS THAT BRING US TOGETHER” Once in a Year Event: Amiel Tours brings 700 tourists to La Traviata Opera at the foothills of Masada! For the third year in a row, Amiel Tours, in collaboration with the The Israel Symphony Orchestra Rishon LeZion has had the privilege of operating the land arrangements for this amazing event. Guests to this landmark event were able to enjoy Verdi’s La Traviata, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 and 9 as well a special performance by internationally recognized Israeli artist, Idan Raichel. With the stars above, the desert wind blowing and the stellar performances by the soloists, this was a one-of-a-kind experience! Start gearing up for the Opera at Masada 2015: June 4, 6 11 & 13 – Tosca June 10 & 12 – Carmina Borana The Late Dr. -

INNOVATION AHEAD Abraham Path Initiative 2019 Annual Report Dear Friend of the Path

abrahampath.org INNOVATION AHEAD ABRAHAM PATH INITIATIVE 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friend of the Path, “Hope,” the great playwright Vaclav Havel take from this region and share with our own once observed, “is not the conviction that neighbors and friends. something will turn out well, but the While the walking paths themselves have certainty that something makes sense sometimes faded, and are divided by regardless of how it turns out.” Hope is the multiple borders, it is API’s privilege to quality we need in today’s times. And the highlight these ancient paths and the local Abraham Path is a path of hope. people with their warm-hearted hospitality. The story of Abraham’s journey has lasted Your encouragement and support helps turn in cultural memory for thousands of years strangers into friends. and inspired millions of people around the world. Abraham (Ibrahim in Arabic) is known With gratitude for bringing hope into our for his hospitality and kindness to strangers world, and that, astonishing as it may seem, is what you find when you walk in his footsteps. I William Ury often reflect on what deep lessons we can Founder and Chair Emeritus ABRAHAM PATH INITIATIVE (API) The Abraham Path Initiative promotes With local partners, API catalyzes API envisions a future in which this walking in Southwest Asia, commonly economic development, community- region may become best known for its called “the Middle East,” as a tool for based tourism, and cultural heritage spectacular walking trails and its warm, intercultural experiences and fostering preservation. Our Fellows recount welcoming people. -

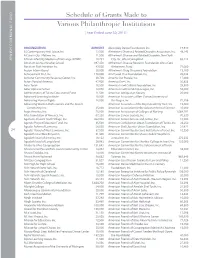

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions

2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL Schedule of Grants Made to Grants Various Philanthropic Institutions American Folk Art Museum 127,350 American Friends of the College of American Friends of Agudat Shetile Zetim, Inc. 10,401 Management, Inc. 10,000 [ Year ended June 30, 2011 ] American Friends of Aish Hatorah - American Friends of the Hebrew University, Inc. 77,883 Western Region, Inc. 10,500 American Friends of the Israel Free Loan American Friends of Alyn Hospital, Inc. 39,046 Association, Inc. 55,860 ORGANIZATION AMOUNT All 4 Israel, Inc. 16,800 American Friends of Aram Soba 23,932 American Friends of the Israel Museum 1,053,000 13 Plus Chai, Inc. 82,950 Allen-Stevenson School 25,000 American Friends of Ateret Cohanem, Inc. 16,260 American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic 52nd Street Project, Inc. 125,000 Alley Pond Environmental Center, Inc. 50,000 American Friends of Batsheva Dance Company, Inc. 20,000 Orchestra, Inc. 320,850 A.B.C., Inc. of New Canaan 10,650 Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, Inc. 44,950 The American Friends of Beit Issie Shapiro, Inc. 70,910 American Friends of the Jordan River A.J. Muste Memorial Institute 15,000 Alliance for Children Foundation, Inc. 11,778 American Friends of Beit Morasha 42,360 Village Foundation 16,000 JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Aaron Davis Hall, Inc. d/b/a Harlem Stage 125,000 Alliance for School Choice, Inc. 25,000 American Friends of Beit Orot, Inc. 44,920 American Friends of the Old City Cheder in Abingdon Theatre Company 30,000 Alliance for the Arts, Inc. -

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

2010 Report on International Religious Freedom » Near East and North Africa » Syria

Syria Page 1 of 8 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » International Religious Freedom » 2010 Report on International Religious Freedom » Near East and North Africa » Syria Syria BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2010 November 17, 2010 The constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, the government imposes restrictions on this right. While there is no official state religion, the constitution requires that the president be Muslim and stipulates that Islamic jurisprudence is a principal source of legislation. The constitution provides for freedom of faith and religious practice, provided that religious rites do not disturb the public order; however, the government restricted full freedom of choice on religious matters. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the government during the reporting period. The government continued to prosecute persons aggressively for their alleged membership in the Muslim Brotherhood or Salafist movements and continued to outlaw Jehovah's Witnesses. In addition the government continued to monitor the activities of all groups, including religious groups, and discouraged proselytizing, which it deemed a threat to relations among religious groups. The government reportedly tolerated Shi'a representatives, paying Sunnis to convert. There were occasional reports of minor tensions among religious groups, some of which were attributable to economic rivalries rather than religious affiliation. Muslim converts to Christianity were sometimes forced to leave their place of residence due to societal pressure. The U.S. government discusses religious freedom with civil society, religious leaders, and adherents of religious groups as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. -

Compete Project Quarterly Report

Compete Project Quarterly Report January 1, 2014 – March 31, 2014 April 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI 1 COMPETE PROJECT QUARTERLY REPORT January 1, 2014 – March 31, 2014 DAI Contract Number: AID-294-C-12-00001 The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID COMPETE PROJECT QUARTERLY REPORT, JANUARY 1 – MARCH 31, 2014 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 5 KEY ACCOMPLISHMENTS ............................................................................................................................. 7 PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS ................................................................................................................................ 14 UPDATE ON COMPONENT B ...................................................................................................................... 18 SUMMARY OF PROGRESS BY SECTOR ....................................................................................................... -

Bay Path Launches Program in Negotiation, Leadership

Talking Points George O'Brien on July 1, 2014 in Education Bay Path Launches Program in Negotiation, Leadership Joshua Weiss was talking about the difference between being assertive and being aggressive. And while doing so, he made it clear that, in the worlds of leadership and negotiation, these terms that appear to be synonymous are anything but. “When you’re assertive, you’re standing on your own two feet, and when you’re aggressive, you’re standing on the other person’s toes, and people often don’t make that distinction,” said Weiss, co- founder of something called the Global Negotiation Initiative at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. He’s also an acclaimed author and consultant in the field who now has a new title on his business card, although they haven’t actually arrived from the printer yet. Joshua Weiss says negotiation isn’t a lost art, but simply one that too many people haven’t taken the Indeed, he is the director of Bay Path College’s time and trouble to master. newest program, the Master of Science in Leadership and Negotiation, or MSLN This fully online initiative is the first of its kind — in this country and probably on a global basis as well, said Weiss, adding quickly that understanding the difference between assertive and aggressive is just one of many things students will learn in this program, which will begin this fall. They’ll also learn how to deal with the concept of power and how to wield it, understand how men and women approach leadership and negotiation differently, learn about the many psychological dimensions of leadership and negotiation, understand the role of emotions in these realms and how to control them, and grasp the importance of relationships and how they go on after the negotiations are over. -

Draft Desk Study Biodiversity Conservation and Community Development in Al-Makhrour Valley in Bethlehem, Palestine

Draft Desk Study Biodiversity Conservation and Community Development in Al-Makhrour Valley in Bethlehem, Palestine 1 Table of Contents Page Preface 3 1-Introduction 4 2. Study area 4 2.1 General 4 2.2 Valley and Battir as a UNSCO World Heritage Site 6 3-Literature review 11 3.1 Introduction 11 3.2 Geology 12 3.3 Geography, Climate, and Ecology 12 3.4 Vertebrate 14 3.4.1 Reptiles and Amphibians 14 3.4.2 Birds 15 3.4.3 Mammals 15 3.5 Invertebrate 16 3.5.1 Gastropods 16 3.5.2 Arachnids 17 3.5.3 Insects 18 3.6 Flora 19 3.7 Anthropological issues incl Agriculture 21 3.8 Ecotourism 29 3.9 Threats and conservation issues 36 3.10 Exploratory trips to the valley and map re-focus 41 4-References 43 5-Preliminary list of Relevant Websites (under development) 54 2 Preface This project titled “Biodiversity Conservation and Community Development in Al-Makhrour Valley in Bethlehem, Palestine” is a British and Palestinian collaboration to conserve biodiversity in Al-Makhrour Valley of Bethlehem (Palestine) benefitting the local communities through sustainable use of ecosystem services. The area is recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site. The objectives included (a) full biodiversity assessment including producing a management plan, (b) promoting agriculture/green practices and ecotourism, and (c) reducing human impact via environmental awareness and education programs while promoting sustainable lifestyles. Project outputs delivered will focus on biodiversity conservation, traditional farming reviving, eco-tourism enhancement, and capacity building. All activities will be done supported with project committees’ consultation, gender inclusion, media coverage, and evaluation. -

Abraham and Israel/Palestine

Journal of Sustainable Tourism ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsus20 Exploring a unifying approach to peacebuilding through tourism: Abraham and Israel/Palestine Jack Shepherd To cite this article: Jack Shepherd (2021): Exploring a unifying approach to peacebuilding through tourism: Abraham and Israel/Palestine, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1891240 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1891240 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 26 Feb 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsus20 JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1891240 Exploring a unifying approach to peacebuilding through tourism: Abraham and Israel/Palestine Jack Shepherd European Tourism Research Institute (ETOUR), Mid Sweden University, Ostersund,€ Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This work emerges from the encouragement of peace studies scholars Received 28 August 2020 to seek out commonalities that can unite rival sides in a conflict. Based Accepted 10 February 2021 on this call, I propose the unifying approach to peacebuilding through KEYWORDS tourism as one where tourism initiatives use unifying points (such as fig- Peacebuilding; guiding ures, sites, stories and symbols) that help conflicting sides see common- fiction; creative analytic alities and thus facilitate cross-cultural understanding. In particular, I practice; Abraham’s Path; look at how the story of Abraham (communal father of Jews, Christians Abraham Hostels; Hostels and Muslims) appears to be used as a guiding fiction for the work of two tourism initiatives in Israel and Palestine. -

Promoting the Holy Family Trail As a Niche Religious Tourism Destination .Papers, Posters, and Presentations

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Papers, Posters, and Presentations 2021 Post Covid-19 Tourism: Promoting the Holy Family Trail as a الترويج ل مسار العائلة /Niche Religious Tourism Destination السياحة بعد 19 المقدسة كوجهة للسياحة الدينية -COVID: Hend Elbehary [email protected] Mona Elsayed [email protected] Nada Abdelghany [email protected] Yasmine Mandour [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/studenttxt Part of the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, and the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Recommended Citation Elbehary, Hend; Elsayed, Mona; Abdelghany, Nada; and Mandour, Yasmine, "Post Covid-19 Tourism: -COVID: الترويج ل مسار العائلة /Promoting the Holy Family Trail as a Niche Religious Tourism Destination .Papers, Posters, and Presentations. 83 .(السياحة بعد 19 المقدسة كوجهة للسياحة الدينية" (2021 https://fount.aucegypt.edu/studenttxt/83 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers, Posters, and Presentations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Post Covid19 Tourism: Promoting the Holy Family Trail as a Niche Religious Tourism Destination A Policy Paper Prepared by: Hend Elbehary Mona Elsayed Nada Abdelghany Yasmine Mandour Under the supervision of: Dr. Hamed Shamma Associate Professor of Marketing & BP Endowed Chair at the School of Business, The American University in Cairo June 2021 *Names are listed in alphabetical order* Published by: The Public Policy HUB The School of Global Affairs and Public Policy (GAPP) The American University in Cairo (AUC) Project Director: Dr. -

Déclaration Sur L'honneur

On the historical traces of Saint James in the Holy Land and the discovery of the cradle of monotheistic religions with the path of Abraham in Palestine Why : Contact during the “Hector Project” – Cultour + (Institute) Assisi and Bethleem are twinned Palestine is “Democracy partner” Assembly parliamentary of Council of Europe Region AuvergneRhoneAlpe is partnership with Masar Ibrahim al Khalil French Agency of Development + French and regional ONG Tetrakys- AFRAT + World Bank -+ EU project . Meet in February and September in Le Puy-en-Velay – In july in Santiago de Compostela Piotr ROZAK (Poland) contacts the St James Cathedral (Jerusalem) - Armenia Church. Intereligious dialogue. St James is born and death in Palestine. His body left the port of Jaffa. We are in the historical roots. Abraham is the foundator father of monotheistic religious. The project Abraham Path is similar to the objectifs of european federation : democracy - cultural and tourism development - Sustainable tourism - High historical value - Heritage and landscape. Exchange of good practice. St James Way is a bridge between Europe and Middle East. Intercultural Dialogue. Program for the delegation of the European Federation Saint James Way - 9th – 14th March 2018 23 persons of 7 countries Day 1: Friday 9th March During day: Arrival to Tel-Aviv airport/Israel 20:00 Introduction meeting and dinner for the delegations arrived Day 2: Saturday 10th March 7:30 : Breakfast 8h00: Walking private tour to Al-Aqsa Mosque – Temple Mount. 9: 00 : Walking – Old City – 05/03/18 1/3 10h00: Meeting at the Armenian church – Saint James Cathedral - Presentation and dialogue; who is Saint James? - Historical presentation - - Visit of the Armenian church Saint James - Meet 13h00: Lunch 14h30 : City tour of Jerusalem old city + Panoramic view – Quaters of Old City Via Dolorosa - Holy Sepulter – Jaffa Gate – Abbey of Dormition – Coenaculum – Cardo - The Western Wall – MT of Olives – Gethsemani – Mary’s Tomb - …. -

The Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School Annual Report

The Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School Annual Report Academic Year 2014-2015 PON Annual Report Index Part One: Report of Activities A. Summary of Academic Year 2014-2015 1. Executive Summary 2. Research, Scholarship and Project Activities a. Areas of Inquiry – Research Program’s Mission Statement b. Projects / Research & Scholarship i. Harvard Negotiation Research Project ii. Harvard Negotiation Project 1. The Harvard International Negotiation Program 2. The Global Negotiation Initiative iii. American Secretaries of State Project iv. The Middle East Negotiation Initiative (MENI) v. MIT-Harvard Public Disputes Program vi. Program on Negotiations in the Workplace vii. PON Research Seminar viii. Leadership and Negotiation c. Clinical Work d. Publications and Other Activities i. Publications 1. Negotiation Journal 2. Negotiation Briefings 3. Harvard Negotiation Law Review 4. Teaching Negotiation 5. Books published by PON-affiliated faculty in 2014- 2015 ii. Conferences iii. Workshops iv. Events 1. American Secretaries of State Project 2. The Herbert C. Kelman Seminar Series on Negotiation, Conflict and the News Media 3. Middle East Negotiation Initiative 4. PON Lunchtime Talks 5. PON Film Series 6. Other Events e. Fellows, Visiting Researchers, Research Assistants and Interns i. 2014-2015 Visiting Scholars and Researchers ii. 2014-2015 PON Graduate Research Fellows iii. PON Summer Research Fellowship Program iv. Student Teaching and Research Assistants v. 2014-2015 PON Interns and Student Assistants 3. Teaching (Contributions to HLS Teaching Program) a. Courses at Harvard Law School b. Teaching Materials and Curriculum Development: The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center c. Negotiation Pedagogy at the Program on Negotiation d. The Harvard Negotiation Institute at the Program on Negotiation (HNI) e.