Abraham and Israel/Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2014 Newslette – Summer

Newsletter August 2014 Israel's leading Tour Operator since 1976 with you all the way! SUMMER 2014 IN ISRAEL SUMMER 2014 IN ISRAEL ”לא יִשָּׁ מַעעֹוד חָמָס בְּאַרְצֵךְ דשֹׁ וָשֶׁ בֶר בִּגְבּולָיִךְ וְקָרָאת יְׁשּועָה חֹומתַיִךְּושְׁ עָרַיִךְ תְּהִלָּה” ”Violence shall no longer be heard in your land, neither robbery nor destruction within your borders, and you shall call salvation your walls and your gates praise.” Isaiah, Chapter 60, Verse 18 Back to Routine As September rolls in and summer fades, Amiel Tours, your Israel destination expert, is coming back better than ever! We have created this special newsletter just for you! Please scroll down and see the many attractions Israel has to offer! עם אחד בלב אחד ONE Nation ONE Heart SOLIDARITY MISSION TO ISRAEL September 8-13, 2014 Please join us in Israel and share the optimism and vision of the Israeli people with us as we stand united. This mission guarantees you an insight into the daily life and reality of living in the South under constant threat. ”THINGS THAT BRING US TOGETHER” Once in a Year Event: Amiel Tours brings 700 tourists to La Traviata Opera at the foothills of Masada! For the third year in a row, Amiel Tours, in collaboration with the The Israel Symphony Orchestra Rishon LeZion has had the privilege of operating the land arrangements for this amazing event. Guests to this landmark event were able to enjoy Verdi’s La Traviata, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 and 9 as well a special performance by internationally recognized Israeli artist, Idan Raichel. With the stars above, the desert wind blowing and the stellar performances by the soloists, this was a one-of-a-kind experience! Start gearing up for the Opera at Masada 2015: June 4, 6 11 & 13 – Tosca June 10 & 12 – Carmina Borana The Late Dr. -

INNOVATION AHEAD Abraham Path Initiative 2019 Annual Report Dear Friend of the Path

abrahampath.org INNOVATION AHEAD ABRAHAM PATH INITIATIVE 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friend of the Path, “Hope,” the great playwright Vaclav Havel take from this region and share with our own once observed, “is not the conviction that neighbors and friends. something will turn out well, but the While the walking paths themselves have certainty that something makes sense sometimes faded, and are divided by regardless of how it turns out.” Hope is the multiple borders, it is API’s privilege to quality we need in today’s times. And the highlight these ancient paths and the local Abraham Path is a path of hope. people with their warm-hearted hospitality. The story of Abraham’s journey has lasted Your encouragement and support helps turn in cultural memory for thousands of years strangers into friends. and inspired millions of people around the world. Abraham (Ibrahim in Arabic) is known With gratitude for bringing hope into our for his hospitality and kindness to strangers world, and that, astonishing as it may seem, is what you find when you walk in his footsteps. I William Ury often reflect on what deep lessons we can Founder and Chair Emeritus ABRAHAM PATH INITIATIVE (API) The Abraham Path Initiative promotes With local partners, API catalyzes API envisions a future in which this walking in Southwest Asia, commonly economic development, community- region may become best known for its called “the Middle East,” as a tool for based tourism, and cultural heritage spectacular walking trails and its warm, intercultural experiences and fostering preservation. Our Fellows recount welcoming people. -

School Sample Itinerary

Eighth Grade Israel Trip April 16 - May 1, 2015 Itinerary by Keshet: The Center for Educational Tourism in Israel This itinerary was created to give the Barrack students a meaningful and memorable Israel experience, one that complements the education that they receive in their respective schools. Through site visits, encounters with Israeli peers, tikun olam programs, and, to whatever extent possible, utilization of the Hebrew language, we hope to enable the participants to strengthen their Jewish commitment and to inspire them to greater identification Israel and the Jewish people. We hope to expose students to the beauty of the ancient, historical narrative while at the same time inspire them with a glimpse of modern, innovative, creative 21st century Israel, on the cutting edge of technology and contributing to a better world today. DATE PROGRAM MEALS/OVERNIGHT Thursday April 16 DEPARTURE ● Depart the US, on flight LY 028 at 1:30 PM Friday, Snack Breakfast lirpA 17 Bruchim Habaim – Welcome to Israel ● 7:00 AM Arrival at Ben Gurion Airport . TC Lunch ● Celebrate our arrival in Israel with Shechehiyanu and the magnificent views of the city of Jerusalem from Mount Scopus. ● Shacharit and breakfast overlooking the old city. ● Visit Ammunition Hill explore issues of the city divided and Shabbat Dinner re-united. ● Head to the Machaneh Yehudah outdoor market for shopping and cash lunch on your own as Jerusalem prepares for Shabbat. ● Check in at the hotel to prepare for Shabbat. Overnight: ● Kabbalat Shabbat at the Kotel. (on the roof in the old city) Jerusalem Tower ● Return to hotel for Shabbat dinner and Oneg Shabbat. -

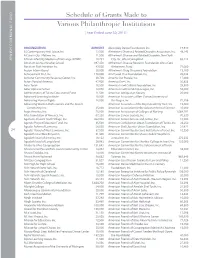

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions

2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL Schedule of Grants Made to Grants Various Philanthropic Institutions American Folk Art Museum 127,350 American Friends of the College of American Friends of Agudat Shetile Zetim, Inc. 10,401 Management, Inc. 10,000 [ Year ended June 30, 2011 ] American Friends of Aish Hatorah - American Friends of the Hebrew University, Inc. 77,883 Western Region, Inc. 10,500 American Friends of the Israel Free Loan American Friends of Alyn Hospital, Inc. 39,046 Association, Inc. 55,860 ORGANIZATION AMOUNT All 4 Israel, Inc. 16,800 American Friends of Aram Soba 23,932 American Friends of the Israel Museum 1,053,000 13 Plus Chai, Inc. 82,950 Allen-Stevenson School 25,000 American Friends of Ateret Cohanem, Inc. 16,260 American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic 52nd Street Project, Inc. 125,000 Alley Pond Environmental Center, Inc. 50,000 American Friends of Batsheva Dance Company, Inc. 20,000 Orchestra, Inc. 320,850 A.B.C., Inc. of New Canaan 10,650 Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, Inc. 44,950 The American Friends of Beit Issie Shapiro, Inc. 70,910 American Friends of the Jordan River A.J. Muste Memorial Institute 15,000 Alliance for Children Foundation, Inc. 11,778 American Friends of Beit Morasha 42,360 Village Foundation 16,000 JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Aaron Davis Hall, Inc. d/b/a Harlem Stage 125,000 Alliance for School Choice, Inc. 25,000 American Friends of Beit Orot, Inc. 44,920 American Friends of the Old City Cheder in Abingdon Theatre Company 30,000 Alliance for the Arts, Inc. -

Israel's Tourism Industry: Recovering from Crises and Generating Growth Stefanie Levit Pace University

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 5-27-2008 Israel's Tourism Industry: Recovering from Crises and Generating Growth Stefanie Levit Pace University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Levit, Stefanie, "Israel's Tourism Industry: Recovering from Crises and Generating Growth" (2008). Honors College Theses. Paper 78. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Israel’s Tourism Industry: Recovering from Crises and Generating Growth By Stefanie Levit E-Mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Graduation Date: May 2008 Major: Hospitality and Tourism Management Advisor: Professor Claudia Green, Hospitality and Tourism Management Table of Contents Précis 3 Introduction to Tourism and its Economic Impact 4 Israel’s Tourism Industry 7 Factors Affecting Tourism to Israel 13 Improving Tourism to Israel 23 Conclusion 27 Works Cited 29 2 Précis In many countries tourism is a vital component of the economy and is an industry in which the home country is proud to show itself off to visitors. Israel is one country in which the tourism industry is still developing and has yet to reach its capacity for visitors. The economic role of tourism in Israel has not always been a major one but over time the industry has grown and become a significant source of revenue. -

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Programa De Pós-Graduação Em História Social MAGNO PAGANELLI DE SOUZA a História Recente Do Turi

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Social MAGNO PAGANELLI DE SOUZA A história recente do turismo religioso brasileiro e seu papel no conflito Israel-Palestina São Paulo 2018 MAGNO PAGANELLI DE SOUZA A história recente do turismo religioso brasileiro e seu papel no conflito Israel-Palestina Tese apresentada a banca examinadora do Programa de Pós-Graduação do Departamento de História da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências, área de concentração em História Social. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Peter R. Demant São Paulo 2018 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. PAGANELLI, Magno. A história recente do turismo religioso brasileiro e seu papel no conflito Israel-Palestina. Tese apresentada a banca examinadora do Programa de Pós- Graduação do Departamento de História da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências, área de concentração em História Social. Aprovado em: Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr. __________________________ Instituição: ___________________________ Julgamento: ________________________ Assinatura: __________________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________ Instituição: ___________________________ Julgamento: ________________________ Assinatura: __________________________ -

Download the PDF File

Alternative TourismJournal Staged Authenticity The Israeli ‘Annexation’ of Palestinian Religious Tourism in the 1967 Occupied Territory 1 Alternative Tourism Journal is an initiative of the Alternative Tourism Group-Study Center Palestine (ATG). It is a journal which offers an alternative narrative of the situation in Palestine and the way it impacts on tourism. ATG is a Palestinian NGO specializing in tours and pilgrimages that include a critical examination of the history, culture, and politics of the Holy Land. ATG operates on the tenets of “justice tourism” and seeks empowerment of the local community through affirmation of Palestinian cultural identity, and protection of eco-rights. Above all, ATG seeks to promote justice in the Holy Land with tourism as one of its instruments. Copyright© ATG-2016 Published in Palestine by the Alternative Tourism Group-Study Center (ATG) Written and Researched by: Dr. Manar Makhoul Design and Layout: Lisa Salsa Kassis Printing: IDEAS - Bethlehem 2 Table of Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 Zionism and Tourism 9 Erasure 9 Appropriation 13 Pilgrimage and Religious Tourism in Palestine 18 Back Stage 23 Performance 34 Conclusion 39 Bibliography 40 3 Introduction Staged Authenticity The Israeli ‘Annexation’ of Palestinian Religious Tourism in the 1967 Occupied Territory 4 Introduction Preface In this study, ATG reinforces the views it has propagated in its previous journals. In the main, we make the claim that Israel’s validation for promoting tourism under its current strategy is two-fold. The study is multi-faceted and, therefore, is intended to attract a variety of readers, researchers, and justice-oriented travelers whose primary reasons for being in the Holy Land is to explore the truth alongside seeing the sites. -

Touristic Entanglements

TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS ii TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS Settler colonialism, world-making and the politics of tourism in Palestine Dorien Vanden Boer Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in the Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences Ghent University July 2020 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Christopher Parker iv CONTENTS Summary .......................................................................................................... v List of figures.................................................................................................. vii List of Acronyms ............................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements........................................................................................... xi Preface ........................................................................................................... xv Part I: Routes into settler colonial fantasies ............................................. 1 Introduction: Making sense of tourism in Palestine ................................. 3 1.1. Setting the scene: a cable car for Jerusalem ................................... 3 1.2. Questions, concepts and approach ................................................ 10 1.2.1. Entanglements of tourism ..................................................... 10 1.2.2. Situating Critical Tourism Studies and tourism as a colonial practice ................................................................................. 13 1.2.3. -

Appropriating the Past – Israel's Archaeological Practices in The

Appropriating the Past Israel’s Archaeological Practices in the West Bank << | < | 1 | > December 2017 Table of Contents Researched and Written by: Ziv Stahl | Legal consulting and assistance with writing Introduction | 3 chapter on the legal background: Atty. Shlomy Zachary | Comments and Editing: Yonathan Mizrachi, Lior Amihai, Miryam Wijler, Yonatan Kanonich, Gideon Suleimani, and Chemi Archaeology in Occupied Territory - Legal Background | 5 Shiff | Legal Consulting: Atty. Ishai Shneydor | Geographic Information and Maps: Hagit Ofran | Hebrew Editing: Anat Einhar | English Translation: Dana Hercbergs | English The Staff Officer for Archaeology - Background for the Management Editing: Talya Ezrahi and Jessica Bonn | Graphic Design: Lior Cohen of Archaeology in the West Bank | 12 Archaeology as a Means for Taking Over Palestinian Lands | 14 Emek Shaveh is an Israeli NGO working to defend cultural heritage rights To whom does the Archaeology Belong? Archaeology as a Tool for and to protect ancient sites as public assets that belong to members of all Dominating the Narrative | 23 communities, faiths and peoples. We object to the fact that the ruins of the past have become a political tool in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict Case Study: Tel Shiloh-Khirbet Seilun on the Lands of Qaryut and work to challenge those who use archaeological sites to dispossess disenfranchised communities. We view heritage site as resources for Village | 32 building bridges and strengthening bonds between peoples and cultures and believe that archaeological sites cannot constitute proof of precedence Conclusion | 39 or ownership by any one nation, ethnic group or religion over a given place. Yesh Din – Volunteers for Human Rights is an Israeli NGO that defends the human rights of Palestinians living in the West Bank under Israeli military rule. -

Tourism in the Mediterranean: Scenarios up to 2030 Robert Lanquar MEDPRO Report No

Tourism in the Mediterranean: Scenarios up to 2030 Robert Lanquar MEDPRO Report No. 1/July 2011- (updated May 2013) Abstract From 1990 to 2010, the 11 countries of the south-eastern Mediterranean region (Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey, hereafter SMCs) recorded the highest growth rates in inbound world tourism. In the same period, domestic tourism in these countries also increased rapidly, which is astonishing given the security risks, natural disasters, oil prices rises and economic uncertainties in the region. Even the 2008 financial crisis had no severe impact on this growth, confirming the resilience of tourism and the huge potential of the SMCs in this sector. The Arab Spring brought this trend to an abrupt halt in early 2011, but it may resume after 2014 with the gradual democratisation process, despite the economic slowdown of the European Union – its main market. This paper looks at whether this trend will continue up to 2030, and provides four different possible scenarios for the development of the tourism sector in SMCs for 2030: i) reference scenario, ii) common (cooperation) sustainable development scenario, iii) polarised (regional) development scenario and iv) failed development – decline and conflict – scenario. In all cases, international and domestic tourist arrivals will increase. However, three main factors will strongly influence the development of the tourism sector in the SMCs: security, competitiveness linked to the efficient use of ICT, and adjustment to climate change. Keywords: Mediterranean, domestic tourism, international tourism, security, climate change, tourism indicators, tourism's economic contribution, tourism competitiveness, tourism prospects, tourism scenarios. -

2010 Report on International Religious Freedom » Near East and North Africa » Syria

Syria Page 1 of 8 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » International Religious Freedom » 2010 Report on International Religious Freedom » Near East and North Africa » Syria Syria BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2010 November 17, 2010 The constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, the government imposes restrictions on this right. While there is no official state religion, the constitution requires that the president be Muslim and stipulates that Islamic jurisprudence is a principal source of legislation. The constitution provides for freedom of faith and religious practice, provided that religious rites do not disturb the public order; however, the government restricted full freedom of choice on religious matters. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the government during the reporting period. The government continued to prosecute persons aggressively for their alleged membership in the Muslim Brotherhood or Salafist movements and continued to outlaw Jehovah's Witnesses. In addition the government continued to monitor the activities of all groups, including religious groups, and discouraged proselytizing, which it deemed a threat to relations among religious groups. The government reportedly tolerated Shi'a representatives, paying Sunnis to convert. There were occasional reports of minor tensions among religious groups, some of which were attributable to economic rivalries rather than religious affiliation. Muslim converts to Christianity were sometimes forced to leave their place of residence due to societal pressure. The U.S. government discusses religious freedom with civil society, religious leaders, and adherents of religious groups as part of its overall policy to promote human rights.