Rock Climbing Practices of Indigenious Peoples In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Individual Executive Member Decision

NOTICE OF INDIVIDUAL EXECUTIVE MEMBER DECISION ITEM NO. IMD 2008/21 TITLE Wokingham Borough Council response to consultation from Bracknell Forest Borough Council on Issues and Options for the Development Management Housing and Commercial Policies and Sites Development Plan Document DECISION TO BE MADE BY Gary Cowan, Executive Member for Local & Regional Planning DATE OF DECISION 27 March 2008 REPORT TO BE PUBLISHED ON 17 March 2008 INDIVIDUAL EXECUTIVE MEMBER DECISION REFERENCE IMD: 2008/21 TITLE Wokingham Borough Council response to consultation from Bracknell Forest Borough Council on Issues and Options for the Development Management Housing and Commercial Policies and Sites Development Plan Document FOR CONSIDERATION BY Gary Cowan Executive Member for Local & Regional Planning DATE 27 March 2008 WARDS Finchampstead South, Hurst, Westcott and Wokingham Without REPORT PREPARED BY Graham Ritchie on behalf of Heather Thwaites, Acting Corporate Head of Strategy & Partnerships SUMMARY Wokingham Borough Council (WBC) needs to agree its response to the consultation underway by Bracknell Forest Borough Council (BFBC) on the Issues and Options for the Development Management Housing and Commercial Policies and Sites Development Plan Document (the BFBC DPD). The BFBC DPD applies to the whole of Bracknell Forest and amplifies the guidance set out in its approved Core Strategy which was the subject of consultation with this authority. It will when finalised provide more detailed policies on the issues for the management and delivery of new housing, retail and employment development. It will also identify sites for these activities beyond that committed for Amen Corner, Binfield and north of Whitegrove/Quelm Park, Bracknell. Further details on the Issues and Options consultation are available at www.bracknell-forest.gov.uk/dmh. -

Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 5, Issue 3– Pages 301-318 After the “Starchitect:” Wright Finds his Voice after Being Fired By Michael O'Brien * The term ―Starchitect‖ seems to have originated in the 1940’s to describe a ―film star who has designed a house‖ but of late has been understood as an architect who has risen to celebrity status in the general culture. Louis Sullivan, like Daniel Burnham, might have been considered a ―starchitect.‖ Starchitects are frequently associated with a unique style or approach to architecture and all who work for them, adopt this style as their own as a matter of employment. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of these architects, working under and in the idiom of Louis Sullivan for six years, learning to draw and develop motifs in the style of Louis Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright’s firing by Louis Sullivan in 1893 and his rapidly growing family set him on an urgent course to seek his own voice. The bootleg houses, designed outside the contract terms Wright had with Adler and Sullivan caused the separation, likely fueled by both Sullivan and Wright’s ego, which left Wright alone, separated from his ―Lieber Meister‖1 or ―Beloved Master.‖ These early houses by Wright were adaptations of various styles popular in the times, Neo-Colonial for Blossom, Victorian for Parker and Gale, each, as Wright explained were not ―radical‖ because ―I could not follow up on them.‖2 Wright, like many young architects, had not yet codified his ideas and strategies for activating space and form. How does one undertake the search for one’s language of these architectural essentials? Does one randomly pursue a course of trial and error casting about through images that capture one’s attention? Do we restrict our voice to that which has already been voiced in history? Wright’s agenda would have included the merging of space and enclosure with site and nature structured as he understood it from Sullivan’s Ornament. -

ARCHAEOLOGY the Newsletter of the Berkshire Archaeological Society

ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Berkshire Archaeological Society Summer 2012 Vol.14, No.2 Summer Walks and Visits Eagle House Visit: Thursday 21 June Meet at 7.00 pm at Eagle House, the prep school for Wellington College (post code GU47 8PH), for a tour of the grounds, a visit to the very interesting ‘Tudor House’ (www.tudorhouse.org), a talk about the history of the house and, perhaps, cookies to finish. The leader will be Doug Buchanan, the former head teacher at the school. Numbers are limited so please book a place with Anne Harrison at [email protected] or tel. 0118 978 5520. There will be a small charge of £3. Knowl Hill Walk: Wednesday 4 July Meet at 7.00 pm in the Seven Stars lay-by at Knowl Hill on the A4. We will walk over Knowl Hill Common, through the lanes past Lovetts, Frogmore and Ffiennes Farms, to end with a drink at The Cricketers on Littlewick Green. En route we will pass the sites of past, present and future geophysical investigations by BAS members. Walking shoes are recommended and return by car to the lay-by will be arranged. No booking is required but please contact Ann Griffin for more details at [email protected] Warfield Historic Walk: Thursday 19 July Meet at 7.00 pm at Larks Hill car park (opposite Quelm Park), Harvest Ride, Bracknell. Warfield has an ancient but little known history, starting with Iron Age farmsteads. The walk will explore many facets of its past, including a former priory, a gibbet and a brick works, and will be led by Hugh Fitzwilliams. -

The Wren of Warfield

Allotments for Warfield! Jealott’s Hill Community Landshare – Queen’s As many of you will be aware Award for Voluntary Service Warfield Parish Council currently has no allotment sites within The Wren Warfield, despite the Parish Council’s best attempts to acquire land for such. However, as part of Warfield of the new development in Warfield, we are delighted to Newsletter of Warfield Parish Council announce that a first parcel of land has now been made February 2016 (issue 70) available for allotments. The new Quelm Allotments site Parish Office: 7 County Lane, Warfield, RG42 3JP is located close to the Quelm Park roundabout, being Tel: 01344 457777 bounded to the north by Watersplash Lane and the new Open Monday - Friday 9.30am - 12.30pm primary school, to the south by Harvest Ride, to the east Email: [email protected] by the new link road and to the west by Quelm Lane. www.warfieldparishcouncil.gov.uk Planning has started for the site, and Congratulations to Warfield-based Jealott’s Hill Twitter: @WarfieldPC we hope to invite interested residents Community Landshare which, on 13 October, was Facebook: Warfield Parish Council to join us in this work – look out for one of only four Berkshire groups presented with the further information in the next issue of prestigious Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service New Warfield Development the Wren. by the Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire. The Community Land to the west of Avery Lane (known as area 2) Landshare project’s ambition is to share the joy – construction continues on phase 1 of the Berkeley Warfield Community Hub of practical horticulture by recognising the power Homes’ site, including the building of 87 homes at the As part of the development taking place within Warfield, gardening has to enrich people’s lives, especially south western corner of the site towards Frampton’s developer contributions are being made available to those who have a disability or are disadvantaged. -

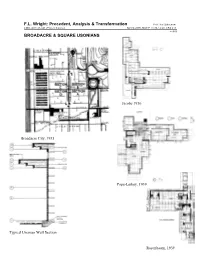

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright 1. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g04297 5. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.il0039 Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Frederick C. Robie House, 5757 Woodlawn Avenue, Lloyd Wright, architect Chicago, Cook County, IL 2. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g01871 House ("Bogk House") for Frederick C. Bogk, 2420 North Terrace Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Stone lintel] http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?pp/hh:@field(DOCID+@lit(PA1690)) Fallingwater, State Route 381 (Stewart Township), Ohiopyle vicinity, Fayette County, PA 3. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/gsc.5a25495 Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction III. 6. 4. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11252 http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?ammem/alad:@field(DOCID+@lit(h19 Frank Lloyd Wright, Baroness Hilla Rebay, and 240)) Solomon R. Guggenheim standing beside a model of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum] / Midway Gardens, interior, Chicago, IL Margaret Carson #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 PREVIOUS NEXT RECORDS LIST NEW SEARCH HELP Item 10 of 375 How to obtain copies of this item TITLE: Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, architect CALL NUMBER: Illus in NA737.W7 A4 1917 (Case Y) [P&P] REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZC4-4297 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZ62-116098 (b&w film copy neg.) SUMMARY: Silhouette of building with steeples on cover of Japanese journal issue devoted to Frank Lloyd Wright, with Japanese and English text. MEDIUM: 1 print : woodcut(?), color. CREATED/PUBLISHED: [1917] NOTES: Illus. -

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright's Destruction of the Box And

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Destruction of the Box and Modern Conceptions of Space Late 19th-early 20th century America was an era of confluence of science, phi- losophy and religion: a contemporary polemic that equated religion (belief based on faith) with science (knowledge based on empirical data of physical phe- nomena). Modernity in 20th century America would be shaped by a pervasive theosophical atmosphere that coupled science with religion to cause a recon- sideration of mental/spiritual relationships and a redefinition of space/time concepts. Theosophy’s introduction of Eastern metaphysics to Western culture revealed possibilities of an inner self with respect to the outer being and opened the way to conceive of inner space, or interiority, and as a result interior space in buildings. To follow is a reconsideration of Wright’s work with respect to the theosophical and occult influences that guided his thinking. His contribution to today’s notion of architecture as a space of continuity will be demonstrated through case studies of his work beginning with the early Dana House (begun in 1899) to the Guggenheim Museum (completed after his death in 1959). EUGENIA VICTORIA ELLIS THE RED SQUARE Drexel University Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) began his practice in 1893 after being fired for “moonlighting” near the end of his five year contract with Adler and Sullivan, one of the then-preeminent Chicago architecture firms. Originally hired to draw the delicate ornamental details of the Auditorium Building interior, another ornamental masterpiece Wright had detailed just debuted at the World’s Columbian Exposition. -

A Retrospective on the Journey

| | EDUCATIONFRANK LLOYD ADVOCACYWRIGHT BUILDING PRESERVATION CONSERVANCY SPRING 2014 / VOLUME 5 / ISSUES 1 & 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE A Retrospective on the Journey Guest Editor: Ron Scherubel Past, Present, Future: The Conservancy at 25 2014 CONFERENCE Phoenix, Arizona | Oct. 29 – Nov. 2 Stay for a great rate in the legendary Wright- influenced Arizona Biltmore. Tour seldom-seen houses by Wright and other acclaimed architects. Get a private behind-the-scenes look at Taliesin celebrating years of saving wright West. Attend presentations and panels with world- 25 renowned Wright scholars, including a keynote speech by New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman. And cap it all off with a Gala Dinner, silent auction, Wright Spirit Awards ceremony, and much more! Register beginning in FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY June at savewright.org or call 312.663.5500 C ON T Editor’s Welcome: OK, What’s Next? 2 EN 2 Executive Editor’s Message: The Power of Community President’s Message: The Challenge Ahead 3 TS 4 Wright and Historic Preservation in the United States, 1950-1975 11 The Origins of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy 16 A Day in the Conservancy Office 20 Retrospect and Prospect 22 The ‘Saves’ in SaveWright 28 The Importance of the David and Gladys Wright House PEDRO E. GUERRERO (1917-2012) 30 Saving the David and Gladys Wright House The cover photo of this issue was taken by 38 A New Book Explores Additions to Iconic Buildings Pedro E. Guerrero, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 42 A Future for the Past trusted photographer. Guerrero was just 22 46 Up Close and Personal in 1939 when Wright took an amused look at his portfolio of school assignments and 49 Executive Director’s Letter: For the Next 25 hired him on the spot to document the con- struction at Taliesin West. -

Film and Architecture: Discovering the Self-Reflection of Frank Capra And

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2000 Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis Marie Lynore Kohler University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Kohler, Marie Lynore, "Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis" (2000). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1120. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/c7iq-fh8b This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiaice, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Quelm Park Annex C

Annexe C Consultation objection details and Bracknell Forest Council’s responses Objector Verbatim Objection Objection Summary BFC response Carol Doran I am writing to object to the appropriation of Objection 1 – There will be an There has been an intention to build the road for 15.09.13 6,010m of land which is currently open unacceptable loss of open many years dating right back to the original recreational land, for the use of building a road. I space/open spaces must be construction of the North Distributor Road (now have looked carefully at the map and it is quite protected. called Harvest Ride) during the 1990's. That was unacceptable to build a road there. I understand planned for along with the residential development that it is Council owned land, but given the huge at Whitegrove and Quelm Park and its associated amounts of development that are planned in the open space. It was included in the North Bracknell Borough, it seems that taking even more land for Local Plan. However that section of the road was an access road is wrong. I also note that the land not built but the section of the road was for the new development was part of the SADPD, safeguarded for the future in the Bracknell Forest but I can find no mention of the use of this open Borough Local Plan. The Council then promoted land or of an access road, in the Land Allocation development in the area via the Core Strategy Documents. DPD and the site was allocated through the Site If I am wrong, perhaps you would be kind enough Allocations Local Plan (SALP). -

Changes to Council Supported Bus Services from 13 July 2015

To get this information, you can: you information, this get To plan their journeys better. better. journeys their plan arrive at each stop, and allows passengers to to passengers allows and stop, each at arrive possible to predict when the bus is likely to to likely is bus the when predict to possible are driven round their routes. This makes it it makes This routes. their round driven are facilities. health local to get to easier technology so they can be tracked as they they as tracked be can they so technology it make and services rail to links improve *Example QR code QR *Example Courtney’s buses are fitted with special special with fitted are buses Courtney’s borough, the in places key other and centre will still allow you to get to Bracknell town town Bracknell to get to you allow still will Real Time’ information Time’ Real and get better value for money. The changes changes The money. for value better get and network to improve services where possible possible where services improve to network charges) the revise to opportunity the taken have cost 12p per minute plus standard network network standard plus minute per 12p cost We 2015. July 12 Sunday, on end services that stop. that information, or call 0871 200 22 33 (calls (calls 33 22 200 0871 call or information, bus supported for contracts existing The website showing real time information for for information time real showing website at www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk to get get to www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk at your smart phone to be taken directly to a a to directly taken be to phone smart your changes? making we are Why You can also visit the Traveline website website Traveline the visit also can You code* at your bus stop. -

Land at Manor Farm Binfield Road Binfield Bracknell Berkshire Proposal: Erection of 24No

Unrestricted Report ITEM NO: 05 Application No. Ward: Date Registered: Target Decision Date: 12/01008/FUL Warfield Harvest Ride 3 January 2013 4 April 2013 Site Address: Land At Manor Farm Binfield Road Binfield Bracknell Berkshire Proposal: Erection of 24no. dwellings with vehicular access from Binfield Road, and associated parking, bin and cycle storage and open space following the demolition of existing outbuildings (resubmission, with amendments, of scheme originally submitted under reference 12/00596/FUL) Applicant: Millgate Homes Agent: (There is no agent for this application) Case Officer: Martin Bourne, 01344 352000 [email protected] Site Location Plan ( for identification purposes only, not to scale ) © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Bracknell Forest Borough Council 100019488 2004 Planning Committee 23rd May 2013 1 RELEVANT PLANNING HISTORY (If Any) 12/00596/FUL Validation Date: 25.07.2012 Erection of 24 dwellings with vehicular access from Binfield Road, and associated parking, bin and cycle storage and open space following the demolition of existing outbuildings. Refused 2 RELEVANT PLANNING POLICIES Key to abbreviations BFBCS Core Strategy Development Plan Document BFBLP Bracknell Forest Borough Local Plan RMLP Replacement Minerals Local Plan WLP Waste Local Plan for Berkshire SPG Supplementary Planning Guidance SPD Supplementary Planning Document MPG Minerals Planning Guidance DCLG Department for Communities and Local Government NPPF National Planning Policy Framework Plan Policy Description (May be