Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis Or Dissertation As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at the Breman Museum

William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History Weinberg Center for Holocaust Education THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES FOR SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY AT THE BREMAN MUSEUM MSS 250, CECIL ALEXANDER PAPERS BOX 1, FILE 10 BIOGRAPHY, 2000 THIS PROJECT WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF THE ALEXANDER FAMILY ANY REPRODUCTION OF THIS MATERIAL WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED WRITTEN CONSENT OF THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum ● 1440 Spring Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30309 ● (678) 222-3700 ● thebreman.org CubaFamily Archives Mss 250, Cecil Alexander Papers, The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at The Breman Museum. THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCIDTECTS October 2, 2000 Ben R. Danner, FAIA Director, Sowh Atlantic Region Mr. Stephen Castellanos, FAIA Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award C/o AlA Honors and Awards Department I 735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20006-5292 Dear Mr. Castellanos: It is my distinct privilege to nominate Cecil A. Alexander, FAIA for the Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award. Mr. Alexander is a man whose life exemplifies the meaning of the award. He is a distinguished architect who has led the effort to foster better understanding among groups and promote better race relations in Atlanta. Cecil was a co-founder, with Whitney Young, of Resurgens Atlanta, a group of civic and business leaders dedicated to improving race relations that has set an example for the rest of the nation. Cecil was actively involved with social issues long before Mr. Young challenged the AlA to assume its professional responsibility toward these issues. -

Archaeological Testing at Allenbrook (9Fu286), Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, Roswell, Georgia

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TESTING AT ALLENBROOK (9FU286), CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER NATIONAL RECREATION AREA, ROSWELL, GEORGIA Chicora Research Contribution 547 ARCHAEOLOGICAL TESTING AT ALLENBROOK (9FU286), CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER NATIONAL RECREATION AREA, ROSWELL, GEORGIA Prepared By: Michael Trinkley, Ph.D. Debi Hacker Prepared For: National Park Service Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area 1978 Island Ford Parkway Atlanta, Georgia 30350 Contract No. P11PC50748 ARPA Permit No. CHAT 2012-001 CHICORA RESEARCH CONTRIBUTION 547 Chicora Foundation, Inc. PO Box 8664 Columbia, SC 29202 803-787-6910 www.chicora.org December 3, 2012 This report is printed on permanent paper ∞ MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The investigations were conducted in saprolite rock that was designated Level 2 and compliance with ARPA Permit CHAT 2012-001 extended from 0.07 to 0.17m bs. This zone under contract with the National Park Service to represented fill and no artifacts were identified. examine archaeological features that may be associated with the foundation wall of the Level 3 was slightly deeper, extending Allenbrook House (9FU286, CHAT-98) and from 0.17 to 0.35m and consisted of identical determine if archaeological evidence of a previous compact mottled red (2.5YR 4/4) clay and porch on the south façade of the structure could saprolite rock that graded into a red clay (2.5YR be identified. 4/6) and saprolite rock. This fill was also sterile. The work was conducted by Dr. Michael Level 4 extended from 0.35 to 0.48m and Trinkley, RPA (who was on-site during the entire consisted of red clay (2.5YR 4/6) and saprolite project), Ms. Debi Hacker, and Mr. -

Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area Visitor Study Summer 2010

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area Visitor Study Summer 2010 Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/SSD/NRR—2011/636/106766 ON THE COVER Photograph courtesy of Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area Visitor Study Summer 2010 Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/SSD/NRR—2011/636/106766 Ariel Blotkamp, Nancy C. Holmes, Dr. Wayde Morse, Steven J. Hollenhorst February 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. Data in this report were collected and analyzed using methods based on established, peer-reviewed protocols and were analyzed and interpreted within the guidelines of the protocols. Views, statements, findings, conclusions, recommendations, and data in this report do not necessarily reflect views and policies of the National Park Service, U.S. -

WATERING GEORGIA: the State of Water and Agriculture in Georgia

WATERING GEORGIA: The State of Water and Agriculture in Georgia A Report by the Georgia Water Coalition | November 2017 About the Georgia Water Coalition Founded in 2002, the Georgia Water Coalition’s (GWC) mission is to protect and care for Georgia’s surface water and groundwater resources, which are essential for sustaining economic prosperity, providing clean and abundant drinking water, preserving diverse aquatic habitats for wildlife and recreation, strengthening property values, and protecting the quality of life for current and future generations. The GWC is a group of more than 240 organizations representing well over a quarter of a million Georgians including farmers, homeowner and lake associations, business owners, sportsmen’s clubs, conservation organizations, professional associations and religious groups who work collaboratively and transparently with each other to achieve specific conservation goals. About Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, Inc. Chattahoochee Riverkeeper’s (CRK) mission is to advocate and secure the protection and stewardship of the Chattahoochee River, including its lakes, tributaries and watershed, in order to restore and conserve their ecological health for the people and wildlife that depend on the river system. Established in 1994, CRK is an environmental advocacy education organization with more than 7,300 members dedicated solely to protecting and restoring the Chattahoochee River Basin. CRK was the 11th licensed program in the international Waterkeeper Alliance, now more than 300 organizations strong. CRK is also a founding member of the GWC. Acknowledgements We wish to thank the C. S. Mott Foundation for its support of this project. Additionally, Gordon Rogers (Flint Riverkeeper) Written by Dr. Chris Manganiello- provided assistance throughout this project. -

Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area Geologic

GeologicGeologic Resource Resourcess Inventory Inventory Scoping Scoping Summary Summary Chattahoochee Glacier Bay National River NationalPark, Alaska Recreation Area Georgia Geologic Resources Division PreparedNational Park by Katie Service KellerLynn Geologic Resources Division October US Department 31, 2012 of the Interior National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior The Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) Program, administered by the Geologic Resources Division (GRD), provides each of 270 identified natural area National Park System units with a geologic scoping meeting, a scoping summary (this document), a digital geologic map, and a geologic resources inventory report. Geologic scoping meetings generate an evaluation of the adequacy of existing geologic maps for resource management. Scoping meetings also provide an opportunity to discuss park-specific geologic management issues, distinctive geologic features and processes, and potential monitoring and research needs. If possible, scoping meetings include a site visit with local experts. The Geologic Resources Division held a GRI scoping meeting for Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area on March 19, 2012, at the headquarters building in Sandy Springs, Georgia. Participants at the meeting included NPS staff from the national recreation area, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, and the Geologic Resources Division; and cooperators from the University of West Georgia, Georgia Environmental Protection Division, and Colorado State University (see table 2, p. 21). During the scoping meeting, Georgia Hybels (NPS Geologic Resources Division, GIS specialist) facilitated the group’s assessment of map coverage and needs, and Bruce Heise (NPS Geologic Resources Division, GRI program coordinator) led the discussion of geologic features, processes, and issues. Jim Kennedy (Georgia Environmental Protection Division, state geologist) provided a geologic overview of Georgia, with specific information about the Chattahoochee River area. -

A River Runs Through It : a 100-Year History of the Columbus Water Works

f� CONTENTS \' 1.-�\ /\ 0 -- 11 Cl\s \..0 v ' � ?\J Acknoi11ledg1nent .....................................................2 Introduction ........................................................3 Pre-History ........................................................4 A Water Works Of Our Own ........................................... 11 WorldWarI:1914-1918 ..............................................16 WorldWarII: 1941-1945 ............................................ 20 A Flood ofGrowth andImprovement ..................................... 24 Fluoridation Question Here ToStay ...................................... 25 Adding Sewage ToThe Mix ............................................ 26 Water: Pure, Not Simple .............................................. 35 January 1, 1971: Columbus Becomes Georgia's First Consolidated City and County Government; One ofSixteen in Nation! ....................... 37 Getting Awards, Still Fighting Battles ......................................3 9 Making Lemonade From Lemons .........................................42 Rolling On ........................................................47 Put Our Service to the Test ..............................................48 Board ofWater Commissioners .......................................... 51 Columbus WaterWorks Presidents .........................................53 ColumbusWater Works Employees .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .5 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS "There are stories all around you here, open up your ears and eyes. There are antebellum remnants near that -

Champion Trees in Atlanta and Georgia.Pages

Champion Trees in Atlanta and Georgia This list is a mashup of information from the 2016 champion tree lists for both Atlanta and Georgia. 48 species are included. Some trees are on both the Atlanta list and the Georgia list. circum height Atlanta List Georgia List (in) (ft) location rank year rank ref # GA county Ash, White 172 133 Louise G. Howard Park/Northside BeltLine trail 1 2010 1 1870 Fulton 169 90 587 Ridgecrest Rd, Atlanta, GA 2 2010 165 64 Agnes Scott College- circular front drive 3 2011 Baldcypress 395 78 Ebenezer 1 1650 Effingham 119 132 Atlanta Memorial Park- fplain past playground 1 2013 Basswood 139 113 Louise G. Howard Park 1 1898 Fulton 85 136 Fernbank Museum 1 2010 1 3463 Dekalb Beech, American 169 115 Lawrenceville 1 1385 Gwinnett 149 122 Lullwater Conservation Park 1 2010 2 1970 Fulton 167 105 Intersection of hwy 36 & 162 3 1945 Newton 138 130 845 Clifton Rd, Atlanta, GA 30307 2 2016 156 103 799 Clifton Rd NE, Atlanta, GA 30307 2 2014 145 121 1275 Beech Valley Rd, Atlanta, GA 2 2014 174 86 860 Barnett St (or Drewry?), Atlanta, GA 2 2011 142 116 1263 Beech Valley Rd, Atlanta, GA 2 2014 126 122 Decatur Cemetery 3 2010 146 77 468 Florida Ave, Atlanta, GA 4 2014 Birch, River 190 85 Covington 1 1386 Newton 120 74 Atlanta Memorial Park- just west of Nside Drive 1 2014 along 103 84 East Palisades, Chattahoochee River NRA 2 2010 104 68 Emory University - Wesley Woods ctr at creek 3 2012 97 72 Medlock Park along PATH 3 2012 Boxelder 161 56 Duluth 1 1600 Gwinnett Cherry, Black 196 83 Ellijay 1 1470 Gilmer 90 111 Herbert Taylor -

Emory University

Georgia’s 2020 CLEAN WATER HEROES Emory University CHATTAHOOCHEE & SOUTH RIVERS WaterHub Relieves Pressure on Water & Sewer Infrastructure INTRODUCTION: In the summer of 2008, Atlanta was reeling from two years of drought. As water use restrictions tightened, water supplies creeped perilously close to running dry. It was a frightening wake up call for a metro region of some six million residents that depended on the diminutive Chattahoochee for its primary water supply. Of course, Emory University in DeKalb County, known as one of the leading research EMORY universities in the nation, was already ahead of the curve. Three years prior to UNIVERSITY that epic drought, the university had already set a goal of cutting its water use in half. By Earth Day 2015, officials were dedicating the school’s WaterHub, an on-campus water treatment/recycling facility that during the past five years has helped supply 40 percent of the school’s water needs. The first of its kind facility in the U.S., it now serves as a model for other communities looking to conserve water and reduce stress on water and sewer infrastructure. THE WATER BODY: Atlanta’s water supply and wastewater treatment systems rely heavily on the Chattahoochee and South rivers. The Chattahoochee supplies drinking water for 40 percent of Georgia’s citizens, including most of those living in metro Atlanta. In fact, no other major city in the U.S. depends upon a smaller river basin for its primary water source. Meanwhile both the Chattahoochee and South are the primary destination for effluent from sewage treatment facilities in DeKalb and Fulton counties. -

Chattahoochee River: # State Fails to Ensure Critical Minimum Flows 7 at Atlanta

2012’s Worst Offenses Against GEORGIA’s WATER CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER: # State Fails to Ensure Critical Minimum Flows 7 at Atlanta Twice in 2012, Bull Sluice Lake, a reservoir on the Chattahoochee River formed by Morgan Falls Dam near Atlanta, nearly disappeared, stranding boaters on mudflats. The sudden drop in Bull Sluice’s elevation was the result of a communication glitch between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), #7 which operates Lake Lanier’s Buford Dam upstream, and Georgia Power Co., which operates Morgan Falls Dam. As a result of the glitch, Chattahoochee River flows below Buford and Morgan Falls dams dipped to unprecedented Chattahoochee River lows with unknown water quality consequences, underscoring an ongoing problem on the river: the lack of timely flow and water quality monitoring. In the 1970s, Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division (EPD) established a minimum flow of 750 cubic feet per second (cfs) in the Chattahoochee River below Morgan Falls Dam at Peachtree Creek in order to dilute discharges from sewage treatment plants in metro Atlanta and to protect the health of the river. Unfortunately, EPD has yet to provide real-time monitoring at this critical location, making compliance with this flow requirement impossible to verify. In addition, since implementing the minimum flow standard more than 30 years ago, EPD has yet to conduct a comprehensive, scientific study to confirm that 750 cfs is adequate to assimilate metro Atlanta’s sewage and protect water quality. THE RIVER: Flowing 436 miles from its headwaters in the North Georgia mountains to its confluence with the Flint River in southwest Georgia, the Chattahoochee is the most heavily used river in the state. -

Candler Park Brook Waterbody Improved in the 1950S, Candler Park Brook Was Piped Into Underground Culverts and Confined in a Surface Concrete Channel

NONPOINT SOURCE SUCCESS STORY Stream Daylighting Restores Atlanta’sGeorgia Candler Park Brook Waterbody Improved In the 1950s, Candler Park Brook was piped into underground culverts and confined in a surface concrete channel. Decades later, the concrete channel was deteriorating and the biological health of the stream was very poor. Neighborhood partners and the City of Atlanta used grant funding from the Clean Water Act (CWA) Section 319(h) Program to remove the underground culverts and surface concrete channel, restore the stream to its natural channel, plant native vegetation and re-establish a narrow floodplain. The health of the stream and its ecosystem improved and now supports small fish, wading birds, beavers and other wildlife. Problem Candler Park Brook is a headwaters stream that drains into Lullwater Creek, Peavine Creek, Peachtree Creek, the Chattahoochee River, and ultimately into the Gulf of Mexico. The brook flows through a public park and golf course in Atlanta (Figure 1). In the 1950s, Candler Park Brook was contained in an underground pipe and a surface concrete channel (Figure 2). After 50 years, the culverts that had housed Photo: MeandersPhoto: River Restoration, Inc. the stream were collapsing, leading to sink holes in the ground surface. The surface concrete channel was also deteriorating. In addition, the brook was impacted by illegal dumping, stormwater overflows and urban runoff. The biological health of the stream was very poor, supporting only fly larvae and aquatic worms, and Figure 1. The restored Candler Park Brook flows through the riparian habitat was virtually nonexistent. Biological an Atlanta park. monitoring and assessment of Candler Park Brook in 1999 indicated impaired biological condition, and removed approximately 850 feet of concrete culvert habitat assessments indicated a poor rating. -

Stakeholders Move to End Water War

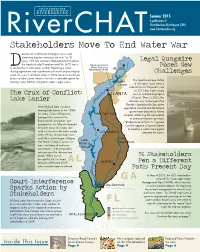

Summer 2015 A publication of Chattahoochee Riverkeeper (CRK) RiverCHAT www.chattahoochee.org Stakeholders Move To End Water War ecades of conflict over Georgia’s most used waterway may be coming to an end. For 21 years, CRK has worked collaboratively throughout Legal Quagmire the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) basin Poses New toD resolve the tri-state water conflict. Reaching a water sharing agreement that is protective of human and ecological Challenges needs for users in all three states is critical because continued access to Lake Lanier remains the most sustainable option for The legal landscape shifted meeting metro Atlanta’s long-term water supply needs. in Georgia’s favor when a federal Court of Appeals ruled in 2011 that water supply The Crux of Conflict: was an authorized purpose of Lanier. Then, in 2013, this Lake Lanier decision was challenged when Florida’s Apalachicola Bay oyster When Buford Dam was built, population crashed and the federal forming Lake Lanier in the 1950s, government declared a fishery the Army Corps of Engineers disaster. Attributing the devastation managed the reservoir for to overconsumption upstream, flood control, navigation and Florida turned to the U.S. Supreme hydropower. As Atlanta’s demand Court to appoint a Special Master for water grew, the Corps also to develop a water-sharing plan used the reservoir for water supply. between the states. In the 1970s, downstream users in all three states began alleging that North Georgia’s water use was unauthorized and over consumptive, with inequitable consequences for downstream needs. When severe 56 Stakeholders drought hit the Southeast between 2006 and 2009, Pen a Different these tensions came to a head. -

Atlanta Heritage Trails 2.3 Miles, Easy–Moderate

4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks 4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks A Comprehensive Guide to Walking, Running, and Bicycling the Area’s Scenic and Historic Locales Ren and Helen Davis Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Copyright © 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All photos © 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is a revised edition of Atlanta’s Urban Trails.Vol. 1, City Tours.Vol. 2, Country Tours. Atlanta: Susan Hunter Publishing, 1988. Maps by Twin Studios and XNR Productions Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Cover design by Maureen Withee Composition by Robin Sherman Fourth Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in August 2011 in Harrisonburg, Virgina, by RR Donnelley & Sons in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Davis, Ren, 1951- Atlanta walks : a comprehensive guide to walking, running, and bicycling the area’s scenic and historic locales / written by Ren and Helen Davis. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56145-584-3 (alk. paper) 1. Atlanta (Ga.)--Tours. 2. Atlanta Region (Ga.)--Tours. 3. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta-- Guidebooks. 4. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta Region--Guidebooks. 5.