The 'Verismo' of Ruggero Leoncavallo: a Source Study of 'Pagliacci' Author(S): Matteo Sansone Source: Music & Letters, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

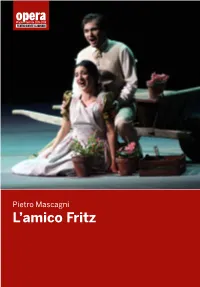

L'amico Fritz

opera Stagione teatrale 2015-2016 TEATRO DANTE ALIGHIERI Pietro Mascagni L’amico Fritz Fondazione Ravenna Manifestazioni Comune di Ravenna Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo Regione Emilia Romagna Teatro di Tradizione Dante Alighieri Stagione d’Opera e Danza 2015-2016 L’amico Fritz commedia lirica in tre atti di P. Suardon musica di Pietro Mascagni Teatro Alighieri 9, 10 gennaio con il contributo di partner Sommario La locandina ................................................................ pag. 5 Il libretto ....................................................................... pag. 6 Il soggetto .................................................................... pag. 23 L’amico Fritz, seconda opera di Mascagni di Fulvio Venturi ........................................................ pag. 25 Guida all’ascolto di Sara Dieci ................................................................ pag. 31 I protagonisti ............................................................. pag. 33 Coordinamento editoriale Cristina Ghirardini GraficaUfficio Edizioni Fondazione Ravenna Manifestazioni Si ringrazia il Teatro Municipale di Piacenza per aver concesso il materiale editoriale. Foto © Gianni Cravedi L’editore si rende disponibile per gli eventuali aventi diritto sul materiale utilizzato. Stampa Edizioni Moderna, Ravenna L’amico Fritz commedia lirica in tre atti dal romanzo omonimo di Erckmann-Chatrian musica di Pietro Mascagni libretto di P. Suardon (Nicola Daspuro) Casa Musicale Sonzogno personaggi e interpreti Suzel -

Composers Mascagni and Leoncavallo Biography

Cavalleria Rusticana Composer Biography: Pietro Mascagni Mascagni was an Italian composer born in Livorno on December 7, 1863. His father was a baker and dreamed of a career as a lawyer for his son, but following the good reception obtained by Mascagni’s first compositions was persuaded to allow him to study music at the Milan Conservatoire, where his teachers included Amilcare Ponchielli and Michele Saladino, and where he shared a furnished room with his fellow-student Giacomo Puccini. His first compositions won him financial support to study at the Milan Conservatory. He was of a rebellious nature and intolerant of discipline, and in 1885 he left the Conservatoire to join a modest operetta company as conductor. He became part of the Compagnia Maresca and, together with his future wife, Lina Carbognani, settled in Cerignola (Apulia) in 1886, where he formed a symphony orchestra. Here Mascagni composed at a single stroke, in only two months, the one-act opera Cavalleria rusticana, based on the short story by Verga, which was to win him the first prize in the Second Sonzogno Competition for new operas. The innovative strength of the opera and the resounding worldwide success which followed its first performance (1890, Teatro Costanzi, Rome) marked the beginning of an artistic life rich in achievements and satisfactions, both as composer and as conductor. He became increasingly prominent as a conductor and in 1892 conducted his opera I Rantzau around Europe. Further successes included Amica (1905) and Isabeau (1911), alongside such failures as Le maschere (1901). In 1915 he experimented with writing for cinema in Rapsodia satanicawith Nino Oxilia. -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

Mascagni E Il Teatro Goldoni: Un Binomio Indissolubile

Mascagni e il Teatro Goldoni: un binomio indissolubile di Alberto Paloscia, Direttore artistico stagione lirica Fondazione Teatro della Città di Livorno “Carlo Goldoni” INTERVENTI Un’altra immagine positore, dopo gli anni di oscura gavetta del giovane Pietro Mascagni prima come direttore di una compagnia girovaga di operette e successivamente come animatore della vita musicale della provincia pugliese nelle veste di fonda- tore e responsabile della Filarmonica di Cerignola, abbatteva le quinte e i fondali del melodramma un po’ imbalsamato del XIX secolo e fondava, con il crudo ed ele- mentare realismo mediterraneo ereditato da Verga, un nuovo stile operistico: quello del verismo e della “Giovine Scuola Italia- na” a cui si sarebbero affiliati, di lì a poco, i nuovi ‘campioni’ del teatro musicale italia- Mascagni e il Teatro Goldoni Teatro il e Mascagni no: Leoncavallo, Puccini, Giordano, Cilèa. Dal 1890 al 1984: quasi un secolo di spettacoli storici Pietro Mascagni e la sua musica possono nel nome di Mascagni essere considerati a buon diritto i più au- Il 14 agosto 1890, infiammato dalla calura tentici protagonisti della gloriosa storia della riviera labronica, Cavalleria approda operistica del Teatro Goldoni di Livorno. nel maggiore teatro della città di Livorno, Il primo importante capitolo è la première appena tre mesi dopo il trionfo arriso nel- per Livorno dell’opera ‘prima’ del giovane la prestigiosa sede del Teatro Costanzi di astro nascente livornese, destinata a dare Roma all’atto unico vincitore del Concor- una svolta decisiva -

Cavalleria Rusticana I Pagliacci Usporedno Sa Sve Brojnijim Izvedbama Prvi Su Put Zajedno Izvedeni 22

P. Mascagni CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA R. Leoncavallo: I PAGLIAccI Nedjelja, 3. svibnja 2015., 18:30 sati. Foto: Metropolitan opera P. Mascagni CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA R. Leoncavallo: I PAGLIAccI Nedjelja, 3. svibnja 2015., 18:30 sati. THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Pietro Mascagni CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA Opera u jednom činu Libreto: Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti i Guido Menasci prema istoimenoj noveli Giovannija Verge NEDJELJA, 3. SVIBNJA 2015. POčETAK U 18 SATI I 30 MINUTA. Praizvedba: Teatro Costanzi, Rim, 17. svibnja 1890. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Druga operna stagiona, Zagreb, 29. svibnja 1893. Prva izvedba ansambla Metropolitana 4. prosinca 1891. u Chicagu Premijera ove izvedbe u Metropolitanu: 14. travnja 2015. ZBOR I ORKESTAR METROPOLITANA SANTUZZA Eva-Maria Westbroek ZBORovođa Donald Palumbo TURIDDU Marcelo Álvarez DIRIGENT Fabio Luisi ALFIO George Gagnidze REDATELJ David McVicar LUCIA Jane Bunnell SCENOGRAF Rae Smith LOLA Ginger Costa-Jackson Tekst: talijanski Stanka poslije Cavallerije rusticane. Titlovi: engleski Svršetak oko 22 sata. Ruggero Leoncavallo I PAGLIACCI Foto:Metropolitan opera Opera u dva čina s prologom Libreto: skladatelj NEDJELJA, 3. SVIBNJA 2015. POčETAK U 18 SATI I 30 MINUTA. Praizvedba: Teatro Dal Verme, Milano, 21. kolovoza 1892. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Treća operna stagiona, Zagreb, 22. travnja 1894. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 11. prosinca 1893. Premijera ove izvedbe u Metropolitanu: 25. travnja 2015. KOSTIMOGRAF Moritz Junge CANIO/PAGLIACCIO Marcelo Álvarez OBLIKOVATELJICA RASVJETE Paule Constable NEDDA/COLOMBINA Patricia Racette KOREOGRAF Andrew George TONIO/TADDEO George Gagnidze KONZULTANT ZA VODVILJ Emil Wolk BEPPE/ARLECCHINO Andrew Stenson SILVIO Lucas Meachem Tekst: talijanski Titlovi: engleski CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA Radnja se događa na Uskrs u sicilijanskom selu. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

Download the Monthly Film & Event Calendar

SAT 2:00 Film SAT 7:00 Film SAT 7:00 Film 4:00 Film Hale County Ugetsu. T3 Suzakumon. T2 The Devil’s Temple. Film & Event Calendar 7 This Morning, This 14 21 T2 Events & Programs 7:00 Film 10:20 Family Evening. T1 10:20 Family 10:20 Family WED An Evening with 6:30 Film Gallery Sessions Explore This! Activity Stations Tours for Fours. Tours for Fours. Tours for Fours. 4:30 Film Shannon Plumb. T2 Gonza the Spearman. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Sat, Apr 7 & Sun, Apr 8, Education & Education & Education & 25 The Nothing Factory. T2 Museum galleries 1:00–3:00 p.m. Floor 5 Research Building Research Building Research Building 1:30 Film T2 Mr. Blandings Builds 7:00 Film Join us for conversations and Explore art through fun and 10:20 Family 10:20 Family 10:20 Family His Dream House. T2 In the Last Days of activities that offer insightful and engaging activities for all ages. A Closer Look for MON A Closer Look for A Closer Look for SUN WED the City. T1 unusual ways to engage with art. Kids. Education & Kids. Education & Kids. Education & 4:30 Film Free with admission 1 4 Research Building 9 Research Building Research Building Gonza the Spearman. Limited to 25 participants SUN See moma.org for TUE T2 Family Films: Yum! Films 10:20 Family 7:30 Event 1:00 Family 1:30 Film 12:00 Family up-to-date listings. 29 Art Lab: Nature About Food Tours for Fours. -

OPERA GLOSSARY – the CULTURE CONCEPT CIRCLE Aficionado - a Devoted Fan Or Enthusiast

OPERA GLOSSARY – THE CULTURE CONCEPT CIRCLE aficionado - A devoted fan or enthusiast. apron - The front part of the stage between the curtain and the orchestra pit. aria - Italian word for "air." a song for solo voice with instrumental accompaniment. baritone - The medium male voice. lies between the low bass voice and the higher tenor voice. baroque - The period of music from the early to mid 1600's to the mid 1700's. Baroque operas are characterized by emotional, highly stylized and flowery presentations. bass - The lowest of the male voices. bass-baritone - A male voice which combines the quality of the baritone with the depth of the bass, avoiding the extremes of either range. basso profundo - The most serious bass voice. bel canto - Italian for "beautiful singing." In a bel canto style opera, the beauty of singing is more important than the plot or the words. bravo! - Bravo is the Italian word for expressing appreciation to a male performer. brava! - Bravo is the Italian word for expressing appreciation to a female performer bravi! - Bravo is the Italian word for expressing appreciation to two or more performers. cadenza - Near the end of an aria, a series of difficult, fast high notes that allow the singer to demonstrate vocal ability. classical - The period in music from roughly the mid 1700's to the early 1800's. coloratura soprano - A very high pitched soprano. also the description of singing which pertains to great feats of agility - fast singing, high singing, trills, and embellishments. commedia dell'arte - A style of dramatic presentation popular in Italy from the 16th century on; the commedia characters were highly stylized and the plots frequently revolved around disguises, mistaken identities and misunderstandings. -

Repertoire Performed Or Recorded Sorted by Composer Birth Year

Robbie Padilla: Repertoire Performed or Recorded Sorted by composer birth year. This list is current as of February 27, 2021. Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625) b. 1580s Voice The Silver Swan (1612) Henry Purcell (1659-1695) b. 1650s Alto Saxophone Two Boureés (trans. Sigurd Rascher) Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) b. 1680s Bassoon Sonata in E-flat Major, TWV 41:EsA1 (1728, ed. Közreadja) Bassoon/Trombone Sonata in F Minor, TWV 41:f1 (1728, ed. Robert Veyron-Lacroix) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Solo Prelude and Fugue in C Major, BWV 846 (1722) Prelude and Fugue in C# Major, BWV 848 (1722) Prelude and Fugue in C# Minor, BWV 849 (1722) Prelude and Fugue in D Major, BWV 850 (1722) Prelude and Fugue in E Major, BWV 854 (1722) Prelude and Fugue in F Minor, BWV 881 (1742) Viola Sonata in B Minor, BWV 1014 (1723, ed. Eric Gustafson) George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Voice Sì, tra i ceppi from Berenice, HWV 38 (1737) Flute Sonata in E Minor, Op. 1, No. 1b, HWV 359b (1724) Benedetto Marcello (1686-1739) Oboe Concerto in D Minor, S D935 (1715, ed. Richard Lauschmann) (I. Allegro…) Euphonium/Tuba Sonata No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 1, No. 2 (1732, arr. Michael D. Blostein) Padilla Repertoire List, page 1 Johann Ernst Galliard (1687-1747) Trombone Sonata No. 1 (1733, ed. Keith Brown) Tuba Galliard Suite (arr. Michael J. Coldren) Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) b. 1730s Solo Sonata in C Major, Hob.XVI:50 (1795) Jean-Paul-Égide Martini (1741-1816) b. 1740s Voice Plaisir d’amour (1784) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) b. -

Catalogo Nov2003.Pdf

Via Savona 12, 20144 Milano - tel/fax 02.89401623 - e-mail: [email protected] CATALOGO - POP / ROCK > A-G < novembre 2003 AUTORE/GRUPPO TITOLO ANNO CASA DISCOGRAFICA CODICE STAMPA N/U/O PREZZO A-HA Hunting high and low 1986 REPRISE 9204830 Tedesca LP-U MIX 5,5 ABBA Greatest hits vol.2 1979 ATLANTIC 16009 Americana LP-U 8 ABBA Arrival 1976 POLYDOR 2310483 Olandese LP-U 10,5 ADAM AND THE ANTS Prince charming 1981 CBS 85268 Italiana LP-U 5,5 ADAM AND THE ANTS Strip 1983 CBS 25705 Italiana LP-U 5,5 AEROSMITH Rocks 1976 CBS 32360 Olandese LP-U 6 AFRIKA BAMBAATAA AND FAMILY Decade of darkness 1991 D.F.C. 57705 Italiana LP-U 5,5 ALABAMA Just us 1987 RCA 86495 Italiana LP-U 5,5 ALARM Eye of the hurricane 1987 I.R.S. 42061 Canadese LP-U 5,5 ALBION BAND Rise up like the sun 1978 ATTIC 1047 Canadese LP-U 15,5 ALBION BAND Under the rose 1984 SPINDRIFT 110 Inglese LP-U 5,5 ALIEN SEX FIEND R.i.p. 1984 ANAGRAM 18 Francese LP-U MIX 8 ALLEN DAEVID Now is the happiest time.... 1977 AFFINITY 3 Inglese LP-U 13 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND Wipe the check the oil .... 1976 CAPRICORN 2637103 Americana DBL LP-U 31 ALPHA BAND Spark in the dark 1977 ARISTA 4145 Americana LP-U 10,5 ALVIN DAVE Romeo’s escape 1986 EPIC 40921 Canadese LP-U 8 AMEN CORNER Greatest hits 1978 IMMEDIATE(LINEA TRE) 33059 Italiana LP-U 5,5 AMERICA Homecoming 1972 WARNER 46180 Francese LP-U 10,5 AMERICA History greatest hits 1975 WARNER BROS 56169 Italiana LP-U 5,5 AMERICA The very best 1991 FIVE RECORDS 30002 Italiana LP-U 5,5 AMERICA Hliday 1974 WARNER BROS. -

Introduction: on Not Singing and Singing Physiognomically

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00426-9 - Opera Acts: Singers and Performance in the Late Nineteenth Century Karen Henson Excerpt More information Introduction: On not singing and singing physiognomically Here you are, my dear Berty, an When the French baritone Victor Maurel wrote this image of the Don Giovanni your old to his son from New York City in 1899, he had just papa just presented to the New York enjoyed an extraordinary ten years performing public. In spite of squalls and storms around the world as Giuseppe Verdi’s first Iago and endured on land and sea, the ravages ff of time don’t seem to show up too Falsta , but was heading into the twilight of his much on my physiognomy, which I career, into a last half-decade of appearances in the think has the chic and youthfulness repertory. The note is written on the back of a appropriate to the character. photographic postcard (or “cabinet card”) that cap- ... What do you think? When I tures him on the occasion of one of those appear- have the full set [of photographs] I’ll ances, as Don Giovanni at the Metropolitan Opera. send them to you; in the meantime ’ accept the affectionate kisses of a The image, which is indeed part of a set by the Met s father who loves you dearly.1 first regularly employed photographer, Aimé Dupont, is well known to specialists of historical singing, but Maurel’s personalization of his copy is striking and unique. Along with the wistful reference to his age and the affectionate greeting, the baritone manages to offer a miniature disquisition on the character of Mozart’s anti-hero, whom he hopes to have presented with “chic” and “youthfulness” (Figure 0.1).