The Gospel of Paul 3/17/10 1:27 PM Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCH 12, 2017 JMJ Dear Parishioners, This Second Week of Lent We Will Again Look at Why We Are Praying the Mass the Way We Are Here at Saint Mary’S

SECOND S UNDAY OF LENT MARCH 12, 2017 JMJ Dear Parishioners, This second week of Lent we will again look at why we are praying the Mass the way we are here at Saint Mary’s. Mass celebrated ver- sus populum has the danger of putting the gathered community and the priest himself, instead of the Eucharist, as the center of worship. At its worst, a cult of personality can be built up around whichever priest “presider” is funniest and most effusive. Like a comedian playing to an audience, the laughter of the congregation at his quirks and eccentricities can even build up a certain clerical narcissism within himself. The celebration of Mass versus populum places the priest front and center, with all of his eccentricities on display. Even priests such as myself who make every effort to celebrate Mass versus populum with a staidness and sobriety easily succumb to its inherent deficiencies. In fact, celebrating the Mass versus populum is just as distracting to the congregation as it is to the priest. While celebrating Mass ad orientem does not immediately cure every moment of distraction, it provides a concrete step in reorienting the focus of the Mass. It allows for a certain amount of anonymity for the priest, restoring the importance of what he does rather than who he is. By returning the focus to the Eucharist, ad orientem worship also restores a sense of the sacred to the Mass. Recalling Aristotle’s definition of a slave as a “living tool,” Msgr. Ronald Knox encouraged this imagery when thinking of the priest: “[T]hat is what the priest is, a living tool of Jesus Christ. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The churches and the bomb = an analysis of recent church statements from Roman Catholics, Anglican, Lutherans and Quakers concerning nuclear weapons Holtam, Nicholas How to cite: Holtam, Nicholas (1988) The churches and the bomb = an analysis of recent church statements from Roman Catholics, Anglican, Lutherans and Quakers concerning nuclear weapons, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6423/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Churches and the Bomb = An analysis of recent Church statements from Roman Catholics, Anglican, Lutherans and Quakers concerning nuclear weapons. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Nicholas Holtam M„Ae Thesis Submitted to the University of Durham November 1988. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Rene Matthew Kollar. Permanent Address: Saint Vincent Archabbey, 300 Fraser Purchase Road, Latrobe, PA 15650. E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 724-805-2343. Fax: 724-805-2812. Date of Birth: June 21, 1947. Place of Birth: Hastings, PA. Secondary Education: Saint Vincent Prep School, Latrobe, PA 15650, 1965. Collegiate Institutions Attended Dates Degree Date of Degree Saint Vincent College 1965-70 B. A. 1970 Saint Vincent Seminary 1970-73 M. Div. 1973 Institute of Historical Research, University of London 1978-80 University of Maryland, College Park 1972-81 M. A. 1975 Ph. D. 1981 Major: English History, Ecclesiastical History, Modern Ireland. Minor: Modern European History. Rene M. Kollar Page 2 Professional Experience: Teaching Assistant, University of Maryland, 1974-75. Lecturer, History Department Saint Vincent College, 1976. Instructor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1981. Assistant Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1982. Adjunct Professor, Church History, Saint Vincent Seminary, 1982. Member, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1981-86. Campus Ministry, Saint Vincent College, 1982-86. Director, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1983-84. Associate Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1985. Honorary Research Fellow King’s College University of London, 1987-88. Graduate Research Seminar (With Dr. J. Champ) “Christianity, Politics, and Modern Society, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1987-88. Rene M. Kollar Page 3 Guest Lecturer in Modern Church History, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1988. Tutor in Ecclesiastical History, Ealing Abbey, London, 1989-90. Associate Editor, The American Benedictine Review, 1990-94. -

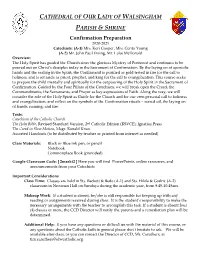

Confirmation Preparation 2020-2021 Catechists: (A-1) Mrs

CATHEDRAL OF OUR LADY OF WALSINGHAM PARISH & SHRINE Confirmation Preparation 2020-2021 Catechists: (A-1) Mrs. Keri Cooper, Mrs. Cerita Young (A-2) Mr. John Paul Ewing, Mr. Luke McDonald Overview: The Holy Spirit has guided the Church since the glorious Mystery of Pentecost and continues to be poured out on Christ’s disciples today in the Sacrament of Confirmation. By the laying on of apostolic hands and the sealing in the Spirit, the Confirmand is purified as gold tested in fire for the call to holiness, and is set aside as priest, prophet, and king for the call to evangelization. This course seeks to prepare the child mentally and spiritually for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the Sacrament of Confirmation. Guided by the Four Pillars of the Catechism, we will break open the Creed, the Commandments, the Sacraments, and Prayer as key expressions of Faith. Along the way, we will consider the role of the Holy Spirit as Guide for the Church and for our own personal call to holiness and evangelization, and reflect on the symbols of the Confirmation rituals – sacred oil, the laying on of hands, naming, and fire. Texts: Catechism of the Catholic Church The Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version, 2nd Catholic Edition (RSVCE), Ignatius Press The Creed in Slow Motion, Msgr. Ronald Knox Assorted Handouts (to be distributed by teacher or printed from internet as needed) Class Materials: Black or Blue ink pen, or pencil Notebook Commonplace Book (provided) Google Classroom Code: [ 2mzeki2 ] Here you will find PowerPoints, online resources, and announcements from your Catechists Important Considerations Class Time: Classes are held in Sts. -

Iraqi Archbishop Freed Unharmed After Kidnapping

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 5 Editorial . 4 Question Corner . 15 Sunday and Daily Readings . 15 Serving the ChurchCriterion in Central and Souther n Indiana Since 1960 www.archindy.org January 21, 2005 Vol. XXXXIV, No. 15 75¢ Iraqi archbishop freed unharmed after kidnapping VATICAN CITY (CNS)—A Catholic captors had treated him well and freed “This morning, they came to tell me Vatican’s nuncio in Baghdad, Iraq, said it archbishop was freed unharmed in Mosul, him soon after they discovered he was a that even the pope had asked for my was difficult to say whether the kidnap- Iraq, less than 24 hours after he was kid- Catholic bishop. release, and I answered, ‘Thank God.’ On ping was part of a wave of terrorism napped by unidentified gunmen. “I’m very happy to the basis of the conversations I had with before the Jan. 30 national elections or Pope John Paul II thanked God for the be back in the arch- them, I don’t think they wanted to strike simply “an episode of common criminal- happy ending to the ordeal, and the bishop’s residence, the Church as such,” he said. ity.” Vatican said no ransom was paid for the where many friends and Although there were reports that the Asked whether Iraq was ready for the prelate’s release. faithful gathered to kidnappers had asked for a ransom, elections, Archbishop Casmoussa said: “I Syrian-rite Archbishop Basile Georges meet me,” Archbishop Archbishop Casmoussa said he was freed don’t think this is the right moment. The Casmoussa of Mosul was released on Jan. -

The Catholic Church and Conversion

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND CONVERSION BY G. K. CHESTERTON Nihil Obstat: Arthur J. Scanlan, S.T.D. Censor Librorum. Imprimatur: Patrick Cardinal Hayes +Archbishop, New York. New York, September 16, 1926. Copyright, 1926 by MacMillan Company EDITOR'S NOTE It is with diffidence that anyone born into the Faith can approach the tremendous subject of Conversion. Indeed, it is easier for one still quite unacquainted with the Faith to approach that subject than it is for one who has had the advantage of the Faith from childhood. There is at once a sort of impertinence in approaching an experience other than one's own (necessarily more imperfectly grasped), and an ignorance of the matter. Those born into the Faith very often go through an experience of their own parallel to, and in some way resembling, that experience whereby original strangers to the Faith come to see it and to accept it. Those born into the Faith often, I say, go through an experience of scepticism in youth, as the years proceed, and it is still a common phenomenon (though not so often to be observed as it was a lifetime ago) for men of the Catholic culture, acquainted with the Church from childhood, to leave it in early manhood and never to return. But it is nowadays a still more frequent phenomenon-- and it is to this that I allude--for those to whom scepticism so strongly appealed in youth to discover, by an experience of men and of reality in all its varied forms, that the transcendental truths they had been taught in childhood have the highest claims upon their matured reason. -

Catholic Truth League

Catholic Truth League [Date]1 September 2017 Induite vos arma Dei Ineffable Creator, who from the treasures of your wisdom, have established three hierarchies of angels, have arrayed them in marvelous order above the fiery Heavens, and have marshaled the regions of the universe with such artful skill, You are proclaimed the True Font of Light and Wisdom, and the primal origin raised high beyond all things. Pour forth a ray of your brightness into the darkened places of my mind; disperse from my soul the twofold darkness into which I was born: sin and ignorance. You make eloquent the tongues of infants. Refine my speech, and pour forth upon my lips the goodness of your blessings. Grant to me keenness of mind, capacity to remember, skill in learning, subtlety to interpret and eloquence in speech. May you guide the beginning of my work, direct its progress, and bring it to completion. You who are True God and True Man, who live and reign world without end. Amen. (St. Thomas Aquinas) Our Lady of Fatima, Pray for Us! This Week in CTL Meeting Schedule* Topic : Introduction September 1 Callout What is CTL?: September 8 Communion of 1. Our mission is to defend, to live, and to Saints propagate our Catholic faith with fidelity September 15 Divinity of Christ and orthodoxy September 22 Existence of God 2. We meet on Fridays to discuss different topics of study within Catholicism September 29 Purgatory 3. We do host some PCS seminars and a October 13 Marian caroling event at the end of this semester Devotions/Private Revelations Apologetics: October 20 Resurrection of the 1. -

The Holy Spirit and the Early Church: the Experience of the Spirit

Page 1 of 7 Original Research The Holy Spirit and the early Church: The experience of the Spirit Author: Firstly, the present article explored the occurrence of special gifts of the Holy Spirit (charismata) Johannes van Oort1,2 both in the New Testament and in a number of early Christian writers (e.g. Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian and Augustine). Secondly, it indicated how this experience of special Affiliations: 1Radboud University charismata exerted its influence on the formulation of the most authoritative and ecumenical Nijmegen, The Netherlands statement of belief, viz. the Creed of Nicaea-Constantinople (381). 2Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa Introduction My previous article in this journal (Van Oort 2011) gave an outline of the development of the Note: 1 Prof. Dr Johannes van Oort doctrine about the Holy Spirit , with specific reference to ecclesiastical writers of both the Eastern is Professor Extraordinarius and Western traditions. In that article, I also examined the development of early Christian in the Department of Church confessions, during which it was noticed that early Christian creedal formulas always display History and Church Polity of a tripartite structure. The reason for this structure was mainly that baptismal candidates were the Faculty of Theology at the University of Pretoria, immersed three times, each immersion coinciding with a question and answer about each of South Africa. the three persons of the Trinity respectively. These formulas eventually developed into fixed symbols. As such, it is understandable why creeds from both the West and the East, such as Correspondence to: the so-called Apostle’s Creed or Symbolum Apostolorum, as well as the Creed of Nicaea of 325 Hans van Oort (which was endorsed and supplemented at the council of Constantinople in 381 and should Email: therefore officially be termed the Creed of Nicaea-Constantinople), all speak of the Holy Spirit [email protected] in their third sections. -

Course Description Course Rationale

Notre Dame Seminary School of Theology SL 602 – Liturgical Space and Time Spring 2013 Professor: Rev. Nile C. Gross Phone: 504-866-7426 (x3919) Email: [email protected] Office Hours: SJ 109, by appointment Classroom: 3 Class Time: Thurs., 1:30-3:15PM Course Description “As sacrament, the Church is Christ’s instrument. ‘She is taken up by him also as the instrument for the salvation of all,’ ‘the universal sacrament of salvation,’ by which Christ is ‘at once manifesting and actualizing the mystery of God’s love for men’” (CCC 776). The Church is the sacramental instrument employed by Christ her Head for the sanctification of the world. Most considerations of this theme of the Church’s sanctifying role rightly emphasize man’s sanctification through her. However, mankind alone is not the object of salvation; all of creation must be brought together in Christ. In this course, we will discuss how the Church, who shares Christ’s mission to “make all things new,” participates in the sanctification of created space and time. Firstly, we will examine how the Church’s prayer itself serves to consecrate time. This investigation will have three main foci – the Divine Office (daily), Sunday worship (weekly), and the Liturgical Year (yearly). Secondly, we will examine how the Church sanctifies space. Here, we will concern ourselves primarily with our church buildings, their architecture and décor. As this is a class in liturgical theology, we will remain focused on the principles established by the Church which allow us, as her members, to more fully recognize and participate in this action of sanctifying the world. -

Prayers Before & After

PRAYERS BEFORE & AFTER WELCOME TO THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS PRAYER OF SAINT AMBROSE PRAYER OF SAINT BONAVENTURE BEFORE HOLY MASS: AFTER HOLY MASS: CATHOLIC CHURCH I draw near, loving Lord Jesus Christ, to the table of Pierce, O most Sweet Lord Jesus, my your most delightful banquet in fear and trembling, a inmost soul with the most joyous and healthful sinner, presuming not upon my own merits, but wound of Thy love, with true, serene, and most trusting rather in your goodness and mercy. I have a holy apostolic charity, that my soul may ever heart and body defiled by my many offenses, a mind languish and melt with love and longing for TWENTIETH SUNDAY OF ORDINARY TIME - AUGUST 18TH, 2019 and tongue over which I have kept no good watch. Thee, that it may yearn for Thee and faint for Therefore, O loving God, O awesome Majesty, I Thy courts, and long to be dissolved and to be Musings from your Parish Priest: turn in my misery, caught in snares, to you the with Thee. Grant that my soul may hunger after The Blessed Virgin Mary’s bodily Assumption into heaven makes clear to us that there is room for our humanity in heaven. fountain of mercy, hastening to you for healing, Thee, the bread of angels, the refreshment of Mary’s Assumption assures us that what Jesus accomplished in rising from the dead and ascending into heaven was not limited to flying to you for protection; and while I do not look holy souls, our daily and supersubstantial bread, his own Person—even though we are not divine, we too are meant to be in heaven with the Incarnate Son, in his home with the forward to having you as Judge, I long to have you having all sweetness and savor and every delight Father and the Holy Spirit. -

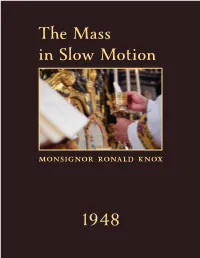

The Mass in Slow Motion 1948

The Mass in Slow Motion MONSIGNOR RONALD KNOX 1948 To purchase a hard copy of this book: http://www.ccwatershed.org/kids/ NIHIL 0BSTAT: E. C. MEssENGER, Ph.D. CENSOR DEPUTATUS lMPRIMA TUR: E. MoRROGH BERNARD Vrc. GEN. WESTMONASTERH, DIE 24A MAn, 1948 To NicOLA ... To learn more about the Campion Hymnal, please visit: CCWATERSHED.ORG/CAMPION PREFACE IF I HAVE a public, this book, I fear, will be a severe test of its patience. That a priest should put on record his private thoughts about the Mass-there is nothing extravagant in that. But mine were put on record in a highly specialized art-form, that of sermons to school-girls; and this form they still impenitently wear. There are films which a child can frequent only by pretending to be an adult. Here are pages which an adult can enjoy only by pretending to be a child. Nisi efficiamini sicut parvuli . The sermons were preached to the convent school of the Assumption Sisters, which was " evacuated " during the late war from Kensington to Aldenham Park in Shropshire. They appeared afterwards in The Tablet, much abridged; by reducing them to less than half their original size, it was possible to give them the air of a contribution designed for that paper. They are now offered to the public almost in their original form. The few excisions which have been made were made reluctantly; no word I had written but recalled some memory not lightly exor cised, and I will not pretend to have finished the business of proof-reading altogether dry-eyed. -

Marriage and the Family (Catholic Truth Society, 1979)

“The Heart of the Deepest Truth” Consultative Document: Marriage and the Family Issued by the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, 15 December 1979 Table of Contents Marriage and the Family: A Consultative Document Foreword Introducing the Theme 1. The Panorama A. Economic Factors B. Social Factors C. Relationship Problems 2. Some Aspects of the Church’s Teaching on Marriage and the Family A. Marriage B. The Family C. Particular Issues 3. The Pastoral Response A. The Family Apostolate B. Needs Of The Family C. Church Initiatives Foreword In October 1980 the International Synod of Bishops will discuss family life. To prepare for that meeting the Synod has already published a preliminary working paper to discover the reactions of Bishops’ Conferences throughout the world. Consequently the bishops have decided to seek the views, experience and findings of people in England and Wales, particularly those with experience of marriage, and of those clergy and laity who have made special study of the many aspects of marriage and family life today. This, then, is not a teaching document; instead its modest purpose is to focus attention on the questions already proposed by the Synod’s preparatory working paper. As it happens, many of these issues are already being discussed in preparation for the National Pastoral Congress in May 1980. The questions raised by the Synod are in some ways wider and more fundamental, and will, of course, prove to be of importance for the Congress itself. The bishops, however, have to respond to the Synod consultation by the end of this year, so the enquiry must be made now; the results will further the Congress discussions in the spring.