4 Three Manifestations of Spatiality in Ambient Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit N9.2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE ALL THE MUSE TI:AT FITS THE PITCH ISSUE NO. 10 JULY -AUGUST 1981 LeRoi, John CaIe, Stones, Blues, 3 Friends, Musso. Give the gift of music. OIfCharlie Parleer + PAGE 2 THE PENN:Y PITCH mJTU:li:~u-:~u"nU:lmmr;unmmmrnmmrnmmnunrnnlmnunPlIiunnunr'mlnll1urunnllmn broke. Their studio is above the Tomorrow studio. In conclusion, I l;'lish Wendy luck, because l~l~ lPIITC~1 I don't believe in legislating morals. Peace, love, dope, is from the Sex Machine a.k.a. (Dean, Dean) p.S. Put some more records in the $4.49 RELIGIOUS NAPOLEON group! 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Dear Warren: (Dear Sex Machine: Titles are being added to (816) 561-1580 I recently came across something the $4.49 list each month. And at the Moon I thought you might "Religion light Madness Sale (July 17), these records is excellent stuff keeping common will be $3.99! Also, it's good to learn that people quiet." --Napoleon Bonaparte the spirit of t_he late Chet Huntley still can Editor ..............• Charles Chance, Jr. (1769-1821). Keep up the good work. cup of coffee, even one vibrated Assistant Editors ...•. Rev. Frizzell Howard Drake Jay '"lctHUO':V_L,LJLe Canyon, Texas LOVE FINDS LeROI Contributing Writers and Illustrators: (Dear Mr. Drake: I think Warren would Dear Warren: Milton Morris, Sid Musso, DaVINK, Julia join us in saying, "Religion is like This is really a letter to Donk, Richard Van Cleave, Jim poultry-- you gotta pluck it and fry it LeRoi. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Informationen Als

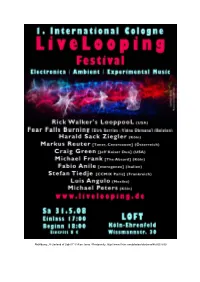

Abbildung: „A Garland of Light II“ © Alan Jaras / Reciprocity, http://www.flickr.com/photos/alanjaras/465037590 Pressemitteilung 1. Internationales Kölner LiveLooping - Festival 31. Mai 2008 im LOFT (Köln), Eintritt 8 Euro, Einlaß 17 Uhr, Beginn 18 Uhr Kontakt und Information: Michael Peters, [email protected], Tel. 02207-912144 Was ist denn „Livelooping“? Livelooping-Musiker sind meist Solo-Musiker, die digitale Loop-Geräte (im Prinzip Echogeräte mit u.U. sehr langer Laufzeit) benutzen, um sich selbst in Echtzeit zu „multiplizieren“, d.h. die live erzeugten Klänge zu wiederholen und zu komplexen Klangschichten aufzutürmen. Das können rhythmische Gebilde sein, aber auch dichte Wolken von Ambient-Klängen. Auch ganze Songstrukturen können live mit Loops aufgebaut und dann als Grundlage für Soli benutzt werden. Der erste Livelooper (damals noch mit Hilfe von Tonbandgeräten = Tape Loops) war der amerikanische Minimalist Terry Riley, der in den späten 60ern mit seinem psychedelischen Loop- Stück „A Rainbow in Curved Air“ und nächtelangen loop-basierten „All Night Flights“ weltbekannt wurde. Später brachte der Ambient-Musik-Erfinder Brian Eno, dessen erstes Ambient-Werk "Discreet Music" mit Tape Loops realisiert wurde, dem King-Crimson-Gitarristen Robert Fripp diese Technik bei. Fripp erzeugte dann in den späten 70ern mit seiner elektrischen Gitarre und seinem „Frippertronics“- Tonbandsystem ungewöhnliche Klanggebilde und machte die Möglichkeiten des Livelooping vor allem Gitarristen bewußt, die nach neuen musikalischen Wegen suchten. Seit den 80ern kann Livelooping mit Hilfe von analogen, später digitalen Loop-Delays erzeugt werden; es gibt mittlerweile eine reichhaltige Auswahl an einfachen und komplexen Loop-Geräten sowie an Software für das Livelooping aus dem Computer. Eine wachsende weltweite Community von Loop-Musikern diskutiert seit über 10 Jahren die technischen und musikalischen Aspekte des Livelooping auf der Loopers Delight-Internet-Mailingliste, und in Amerika, Europa und Japan finden regelmäßig Festivals für Loop-basierte Musik statt. -

Roedelius Bio Engl

ROEDELIUS: JARDIN AU FOU CD and Vinyl Release date: March 27th 2009 Cat No BB23 CD 927892/LP 927891 The essentials: ► Hans-Joachim Roedelius: born 1934; first record release in 1969 with Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Konrad Schnitzler), and active ever since as a solo artist and in various collaborations (amongst others with Moebius/Cluster, Moebius and Michael Rother/Harmonia, as well as with Brian Eno). One of the most prolific musicians of the German avant-garde and a key figure in the birth of Krautrock, synthesizer pop and ambient music. ► Jardin au Fou was first released on the French EGG label in 1979 ► produced by Peter Baumann (Tangerine Dream) ► liner notes by Asmus Tietchens ► CD features six bonus tracks: three remixes, three new tracks One of the most remarkable albums of the so-called Krautrock scene has to be Jardin au Fou by Hans-Joachim Roedelius (Cluster, Harmonia), issued in 1979. All the more noteworthy as it bore no resemblance whatsoever to what was expected of avant-garde electronica and displayed none of the typical Krautrock characteristics. Rhythm machine, sequencer and abstract sounds are conspicuous by their absence. Indeed, listeners were stunned by one of the most beautiful, charming, ethereal and peaceful albums in the history of German rock music. It was produced by Peter Baumann at his own Paragon Studios in 1978, a year after he left Tangerine Dream to concentrate on a solo career and production work. At the time, he was charged by the French label EGG with delivering three productions from the German electro/avant- garde/Krautrock cosmos. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

Icebreaker: Apollo

Icebreaker: Apollo Start time: 7.30pm Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston looks into the history behind Apollo alongside other works being performed by eclectic ground -breaking composers. When man first stepped on the moon, on July 20th, 1969, ‘ambient music’ had not been invented. The genre got its name from Brian Eno after he’d released the album Discreet Music in 1975, alluding to a sound ‘actively listened to with attention or as easily ignored, depending on the choice of the listener,’ and which existed on the, ‘cusp between melody and texture.’ One small step, then, for the categorisation of music, and one giant leap for Eno’s profile, which he expanded over a series of albums (and production work) both song-based and ambient. In 1989, assisted by his younger brother Roger (on piano) and Canadian producer Daniel Lanois, Eno provided the soundtrack for Al Reinert’s documentary Apollo: the trio’s exquisitely drifting, beatific sound profoundly captured the mood of deep space, the suspension of gravity and the depth of tranquillity and awe that NASA’s astronauts experienced in the missions that led to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong taking that first step on the lunar surface. ‘One memorable image in the film was a bright white-blue moon, and as the rocket approached, it got much darker, and you realised the moon was above you,’ recalls Roger Eno. ‘That feeling of immensity was a gift: you just had to accentuate the majesty.’ In 2009, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of that epochal trip, Tim Boon, head of research at the Science Museum in London, conceived the idea of a live soundtrack of Apollo to accompany Reinert’s film (which had been re-released in 1989 in a re-edited form, and retitled For All Mankind. -

An Introduction to Vocal Recording, Sampling, Looping and Effects (Unit 1)

An Introduction to Vocal Recording, Sampling, Looping and Effects (Unit 1) Students will explore and learn the skills required to create music using new sampling, effects and looping technology. The main focus of the scheme of work is to develop an increased awareness of sound through the manipulation of vocally generated sounds. Students will compose and perform pieces of music in conjunction with various pieces of technology. This unit should be studied prior to Unit 2 (Vocalise) and Unit 3 (Film Music) and is written primarily for Year 7 students. This can be adapted for other year groups. Key Concepts: sampling, editing, effects, recording, synthesis, looping Featured Technologies: RC-300, ME-25, DR-30, HPD-10 Age Level: 11 – 14, Year 7 Download Unit Further Resources PPT for Activity 3: BailaBaila vocal samples [link to Unit 1_activity3 folder here] Sample Image for Activity 6 [insert link to comic.jpg here] Sample Image for Activity 7 [insert link to hpd10.jpg here] PPT for Activity 7: Drum Kit [insert link to Unit 1_activity7.ppt here] Vocalise (Unit 2) Students will learn how to use their voices as musical instruments in conjunction with a range of performance and sound processing technologies. They will create ‘sound poetry’, a form of musical and literary composition, within which the phonetic aspects of human speech and noise making are highlighted. Sound Poetry is a performance based activity and, as such, will provide an ideal way to meet the National Curriculum’s new demand for using technologies to support processes of musical performance. The vocal skills that students will learn in this unit are transferable into singing activities and will also generate confidence for future lyric/song writing. -

Download Brian Eno's Another Green World PDF

Download: Brian Eno's Another Green World PDF Free [002.Book] Download Brian Eno's Another Green World PDF By Geeta Dayal Brian Eno's Another Green World you can download free book and read Brian Eno's Another Green World for free here. Do you want to search free download Brian Eno's Another Green World or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Brian Eno's Another Green World | #8242559 in Books | 2017-01-24 | 2017-01-24 | Formats: Audiobook, MP3 Audio, Unabridged | Original language: English | PDF # 1 | 6.75 x .50 x 5.25l, | Running time: 3 Hours | Binding: MP3 CD | |1 of 1 people found the following review helpful.| especially since the book is short (a little over 100 pages) and I wanted to pledge to be Dayal's patron if I liked her book (an | By Christopher Tower |Dayal's book gripped me, and I found that I wanted to keep reading and finish sooner rather than later, especially since the book is short (a little over 100 pages) and I wanted to pledge to be Dayal's patron if I liked her book ( | | "Dayal's unique and fresh take, which also delves into Discreet Music, is a must read for Eno fans and makes a great primer for the uninitiated." -Flagpole Magazine The serene, delicate songs on Another Green World sound practically meditative, but the album itself was an experiment fueled by adrenaline, panic, and pure faith. -

Progressive House: from Underground to the Big Room

PROGRESSIVE HOUSE: FROM UNDERGROUND TO THE BIG ROOM A Bachelor thesis written by Sonja Hamhuis. Student number 5658829 Study Ba. Musicology Course year 2017-2018 Semester 1 Faculty Humanities Supervisor dr. Michiel Kamp Date 22-01-2017 ABSTRACT The electronic dance industry consists of many different subgenres. All of them have their own history and have developed over time, causing uncertainties about the actual definition of these subgenres. Among those is progressive house, a British genre by origin, that has evolved in stages over the past twenty-five years and eventually gained popularity with the masses. Within the field of musicology, these processes have not yet been covered. Therefore, this research provides insights in the historical process of the defining and popularisation of progressive house music. By examining interviews, media articles and academic literature, and supported by case studies on Leftfield’s ‘Not Forgotten’ en the Swedish House Mafia’s ‘One (Your Name)’, it hypothesizes that there is a connection between the musical changes in progressive house music and its popularisation. The results also show that the defining of progressive house music has been - and is - an extensive process fuelled by center collectivities and gatekeepers like fan communities, media, record labels, and artists. Moreover, it suggests that the same center collectivities and gatekeepers, along with the on-going influences of digitalisation, played a part in the popularisation of the previously named genres. Altogether, this thesis aims to open doors for future research on genre defining processes and electronic dance music culture. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 - On the defining of genre ....................................................................... -

Formal Devices of Trance and House Music: Breakdowns

FORMAL DEVICES OF TRANCE AND HOUSE MUSIC: BREAKDOWNS, BUILDUPS AND ANTHEMS Devin Iler, B.M. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2011 APPROVED: David B. Schwarz, Major Professor Thomas Sovik, Minor Professor Ana Alonso-Minutti, Committee Member Lynn Eustis, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Iler, Devin. Formal Devices of Trance and House Music: Breakdowns, Buildups, and Anthems. Master of Music (Music Theory), December 2011, 121 pp., 53 examples, reference list, 41 titles. Trance and house music are sub-genres within the genre of electronic dance music. The form of breakdown, buildup and anthem is the main driving force behind trance and house music. This thesis analyzes transcriptions from 22 trance and house songs in order to establish and define new terminology for formal devices used within the breakdown, buildup and anthem sections of the music. Copyright 2011 by Devin Iler ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF EXAMPLES……………………………………………………………………iv CHAPTER 1—INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………......1 Definition of Terms/Theoretical Background…………………………………......1 A Brief Historical Context………………………………………………………...6 CHAPTER 2— TYPICAL BUILDUP FEATURES……………………………………...9 Snare Rolls and Bass Hits…………………………………………………………9 Bass + Snare + High Hat Leads and Rest Measures……………………………..24 CHAPTER 3— BUILDUPS WITHOUT TYPICAL FEATURES……………………...45 Synth Sweeps…………………………………………………………………….45