SFRA Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

Forte JA T 2010.Pdf (404.2Kb)

“We Werenʼt Kidding” • Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 By Joseph A. Forte Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Robert P. Stephens (chair) Marian B. Mollin Amy Nelson Matthew H. Wisnioski May 03, 2010 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Astounding Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr., sci-fi, science fiction, pulp magazines, culture, ideology, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, American exceptionalism, capitalism, 1939 Worldʼs Fair, Cold War © 2010 Joseph A. Forte “We Werenʼt Kidding” Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 Joseph A. Forte ABSTRACT In 1971, Isaac Asimov observed in humanity, “a science-important society.” For this he credited the man who had been his editor in the 1940s during the period known as the “golden age” of American science fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell was editor of Astounding Science-Fiction, the magazine that launched both Asimovʼs career and the golden age, from 1938 until his death in 1971. Campbell and his authors set the foundation for the modern sci-fi, cementing genre distinction by the application of plausible technological speculation. Campbell assumed the “science-important society” that Asimov found thirty years later, attributing sci-fi ascendance during the golden age a particular compatibility with that cultural context. On another level, sci-fiʼs compatibility with “science-important” tendencies during the first half of the twentieth-century betrayed a deeper agreement with the social structures that fueled those tendencies and reflected an explication of modernity on capitalist terms. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

Outworlds 61

DIANE and XENO From WingNuts Go Hawaiian Copyright © 1991 by Teddy Harvia ALL INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS THIS ISSUE ARE BY: EDITED & PUBLISHED BY BILL BOWERS POBox 58174 • Cincinnati • OH • 45258-0174 DAVID R. HAUGH 1513] 251-0806 COVERS: ALAN HUNTER (OUT)7tEDDY HARVIA (IN) OUTWORLDS is Available by Editorial Whim; or, for Contributions of Art &/or Words; and for Printed LoCs. This Issue: $4.00 § 0W62: $5.00, until 10/1/91 Subscriptions: 5 Issues for $20.00 Copyright (c) 1991, by Bill Bowers; for the Contributors This is My Publication #174 July, 1991 This Issue Dedicated, with Thanks, to: Richard Brandt; Patty Peters & Gary Mattingly; Dick & Leah Smith.... •SEUP u> IT H- BEMS for making Corflu Ocho possible, for me! 61:2003 Chris Sherman Dear Bill; P.O. Box 990 Solana Beach, CA 92075 Hah!’! April 29, 1991 Outworlds at last! Praise the lord, Bowers is alive and printing! Even though I'm familiar with The Saga from Xenolith, reading again about your ordeals provoked empathetic nausea quickly followed by vitriolic (I learned that word from Don Thompson) outrage. I'm not a violent person, but reading about the things you're forced to endure because of "Her" makes me want to... to... words can't express. Sometimes I wish you could subject people like that to surgical, aseptic flaying, the kind Gene Wolfe described in The Shadow of the Torturer. Have you read People of the Lie, by M. Scott Peck? Recommended if you're still seeking "understanding". Peck's conclusion: there are some genuinely evil people in the world. -

Exhibition Hall

exhibition hall 15 the weird west exhibition hall - november 2010 chris garcia - editor, ariane wolfe - fashion editor james bacon - london bureau chief, ric flair - whooooooooooo! contact can be made at [email protected] Well, October was one of the stronger months for Steampunk in the public eye. No conventions in October, which is rare these days, but there was the Steampunk Fortnight on Tor.com. They had some seriously good stuff, including writing from Diana Vick, who also appears in these pages, and myself! There was a great piece from Nisi Shawl that mentioned the amazing panel that she, Liz Gorinsky, Michael Swanwick and Ann VanderMeer were on at World Fantasy last year. Jaymee Goh had a piece on Commodification and Post-Modernism that was well-written, though slightly troubling to me. Stephen Hunt’s Steampunk Timeline was good stuff, and the omnipresent GD Falksen (who has never written for us!) had a couple of good piece. Me? I wrote an article about how Tomorrowland was the signpost for the rise of Steampunk. You can read it at http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/goodbye-tomorrow- hello-yesterday. The second piece is all about an amusement park called Gaslight in New Orleans. I’ll let you decide about that one - http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/gaslight- amusement. The final one all about The Cleveland Steamers. This much attention is a good thing for Steampunk, especially from a site like Tor.com, a gateway for a lot of SF readers who aren’t necessarily a part of fandom. -

S67-00091-N201-1992-11.Pdf

The SFRA Review Published ten times a year for the Science Fiction Research Association by Alan Newcomer, Hypatia Press, 360 West First, Eugene, Oregon, 97401. Copyright © 1992 by the SFRA. Editorial correspondence: Betsy Harfst, Editor, SFRA Review, 2326 E. Lakecrest Drive, Gilbert, AZ 85234. Send changes of address and/or inquiries concerning subscriptions to the Trea surer, listed below. Note to Publishers: Please send fiction books for review to: Robert Collins, Dept. of English, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431-7588. Send non-fiction books for review to Neil Barron, 1149 Lime Place, Vista, CA 92083. Juvenile-Young Adult books for review to Muriel Becker, 60 Crane Street, Caldwell, NJ 07006. Audio-Video materials for review to Michael Klossner, 41 0 E. 7th St, Apt 3, Little Rock, AR 72202 SFRA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President Peter Lowentrout, Dept. of Religious Studies California State University, Long Beach, CA 90840 Vice-President Muriel Becker, Montclair State College Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 Secretary David G. Mead, English Department Corpus Christi State University, Corpus Christi, Texas 78412 Treasurer Edra Bogle Department of English University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-3827 Immediate Past President Elizabeth Anne Hull, Liberal Arts Division William Rainey Harper College, Palatine, Illinois 60067 SFRA Review #201 November 1992 In This Issue: President's Message (Lowentrout) ................................................... 4 News & Information (Barron, et al) ............................................... -

By Lee A. Breakiron ONE-SHOT WONDERS

REHeapa Autumnal Equinox 2015 By Lee A. Breakiron ONE-SHOT WONDERS By definition, fanzines are nonprofessional publications produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, such as a literary or musical genre, for the pleasure of others who share their interests. Readers themselves often contribute to fanzines by submitting their own articles, reviews, letters of comment, and fan fiction. Though the term fanzine only dates from 1940 when it was popularized within science fiction and comic book fandom, the first fanzines actually date back to at least the nineteenth century when, as a uniquely American development, literary groups formed amateur press associations or APAs in order to publish collections of poetry, fiction, and commentary. Few, if any, writers have had as many fanzines, chapbooks, and other ephemera dedicated to them as has Robert E. Howard. Howard himself self-published his own typed “zine,” The Golden Caliph of four loose pages in about August, 1923 [1], as well as three issues of one entitled The Right Hook in 1925 (discussed later). Howard collaborated with his friends Tevis Clyde “Clyde” Smith, Jr., and Truett Vinson in their own zines, The All-Around Magazine and The Toreador respectively, in 1923 and 1925. (A copy of The All-Around Magazine sold for $911 in 2005.) Howard also participated in an amateur essay, commentary, and poetry journal called The Junto that ran from 1928 to 1930, contributing 10 stories and 13 poems to 10 of the issues that survive. Only one copy of this monthly “travelogue” was circulated among all the members of the group. -

Catalogue XVI

Catalogue XVI Welcome to our 16th catalogue, and we think, our finest. 108 items of rare speculative fiction from 1795 right up to 2016. The earth is around 108 sun-diameters from the sun, and in a strange quirk of the cosmos, the earth is around 108 moon-diameters from the moon. This is why the sun and moon are basically the same size in the sky, relative sizes varying by the orbital eccentricities of the earth and moon around the sun and earth respectively. When the sun, moon and earth are in syzygy (yep) this ratio allows for a total solar eclipse. In 1915 Einstein published his paper on general relativity. Despite the fact that Einstein’s theory accounted for the precession of Mercury’s orbit, a flaw with Newtonian physics first identified sixty years earlier, there was general distrust in the notion of spacetime with many of Einstein’s contemporaries preferring the more evidently empirical laws of Newton. Proof was desirable. To measure the warping of spacetime a massive body is needed. Stars are pretty massive, and the sun ain’t too shabby (it’s no Arcturus, but it’s still pretty impressive). In 1919, an experiment was devised to prove general relativity by comparing the relative positions of stars when their emitted light passes close to a massive object to their position when much further away from the massive object. The expected result was that the stars passing close to the sun would have their light warped by the sun’s bending of spacetime. The only problem with testing this was that it’s really difficult to observe stars just over the rim of the sun because, well, the sun’s pretty bright. -

Exhibition Hall Issue 8

exhibition hall issue 8 exhibition hall issue 8 - april 2010 chris garcia - editor, james bacon - london bureau chief ariane wolfe - fashion editor, cover artist: diana vick! What’s the most fine things. This is our at- Steampunk Museum in the tempt, and while they nev- world? The Science Muse- er seem to come up with um of London might have anything, why do I hold a claim with the fact that out hope this time? Be- they’ve got all that Babbage cause I think we’re differ- stuff and steam trains and ent in a way. We still have so on, but I’ll say that it’s the same problems, the the Victoria & Albert Mu- same dealings, but we also seum, just down the way have a bunch of advan- from the Science Museum. tages. We’re a fandom that It’s full of costumes, an- grew on the net. We’re also cient musical instruments, doing all of this earlier in beautiful art, the Hereford our cycle. Also, and maybe Screen, the Cast Courts, Metal work, wood I’m being naive, I think we’re more open stuffs, all sorts of things that the Steampunk and hard-thinking than many other groups might well go nuts over. I love the V&A, and that have tried. You can find the debate at now, a week and a half away from leaving for greatsteampunkdebate.com starting on May the Sceptered Isle of Britain, I’m all a-twitter 1. for the V&A and can’t wait until I make my You’ll read all about my experience at way there. -

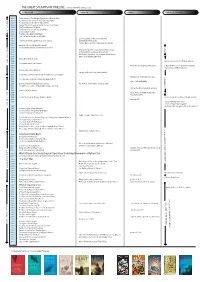

Download the Timeline and Follow Along

THE GREAT STEAMPUNK TIMELINE (to be printed A3 portrait size) LITERATURE FILM & TV GAMES PARALLEL TRACKS 1818 - Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus (Mary Shelley) 1864 - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (Jules Verne) K N 1865 - From the Earth to the Moon (Jules Verne) U P 1869 - Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne) - O 1895 - The Time Machine (HG Wells) T O 1896 - The Island of Doctor Moreau (HG Wells) R P 1897 - Dracula (Bram Stoker) 1898 - The War of the Worlds (HG Wells) 1901 - The First Men in the Moon (HG Wells) 1954 - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Disney) 1965 - The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (Joan Aiken) The Wild Wild West (CBS) 1969 - Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (MGM) 1971 - Warlord of the Air (Michael Moorcock) 1973 - A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (Harry Harrison) K E N G 1975 - The Land That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) U A 1976 - At the Earth's Core (Amicus Productions) P S S 1977 - The People That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) A R 1978 - Warlords of Atlantis (EMI Films) B Y 1979 - Morlock Night (K. W. Jeter) L R 1982 - Burning Chrome, Omni (William Gibson) A E 1983 - The Anubis Gates (Tim Powers) 1983 - Warhammer Fantasy tabletop game > Bruce Bethke coins 'Cyberpunk' (Amazing) 1984 - Neuromancer (William Gibson) 1986 - Homunculus (James Blaylock) 1986 - Laputa Castle in the Sky (Studio Ghibli) 1987 - > K. W. Jeter coins term 'steampunk' in a letter to Locus magazine -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R.