Tezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme Deity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aztec Mythology

Aztec Mythology One of the main things that must be appreciated about Aztec mythology is that it has both similarities and differences to European polytheistic religions. The idea of what a god was, and how they acted, was not the same between the two cultures. Along with all other native American religions, the Aztec faith developed from the Shamanism brought by the first migrants over the Bering Strait, and developed independently of influences from across the Atlantic (and Pacific). The concept of dualism is one that students of Chinese religions should be aware of; the idea of balance was primary in this belief system. Gods were not entirely good or entirely bad, being complex characters with many different aspects and their own desires and motivations. This is highlighted by the relation between Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. When the Spanish arrived with their European sensibilities, they were quick to name one good and one evil, identifying Quetzalcoatl with Christ and Tezcatlipoca with Satan during their attempts to integrate the Nahua peoples into Christianity. But to the Aztecs neither god would have been “better” than the other; they are just different and opposing sides of the same duality. Indeed, their identities are rather nebulous, with Quetzalcoatl often being referred to as “White Tezcatlipoca” and Tezcatlipoca as “Black Quetzalcoatl”. The Mexica, as is explained in the history section, came from North of Mexico in a location they named “Aztlan” (from which Europeans developed the term Aztec). During their migration south they were exposed to and assimilated elements of several native religions, including those of the Toltecs, Mayans, and Zapotecs. -

Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices

1 Multilingual Discourses Vol. 1.2 Spring 2014 Tanya Ball The Power of Death: Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices hrough an examination of Aztec death iconography in pre- and post-Conquest codices of the central valley of Mexico T (Borgia, Mendoza, Florentine, and Telleriano-Remensis), this paper will explore how attitudes towards the Aztec afterlife were linked to questions of hierarchical structure, ritual performance and the preservation of Aztec cosmovision. Particular attention will be paid to the representation of mummy bundles, sacrificial debt- payment and god-impersonator (ixiptla) sacrificial rituals. The scholarship of Alfredo López-Austin on Aztec world preservation through sacrifice will serve as a framework in this analysis of Aztec iconography on death. The transformation of pre-Hispanic traditions of representing death will be traced from these pre- to post-Conquest Mexican codices, in light of processes of guided syncretism as defined by Hugo G. Nutini and Diana Taylor’s work on the performative role that codices play in re-activating the past. These practices will help to reflect on the creation of the modern-day Mexican holiday of Día de los Muertos. Introduction An exploration of the representation of death in Mexica (popularly known as Aztec) pre- and post-Conquest Central Mexican codices is fascinating because it may reveal to us the persistence and transformation of Aztec attitudes towards death and the after-life, which in some cases still persist today in the Mexican holiday Día de Tanya Ball 2 los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. This tradition, which hails back to pre-Columbian times, occurs every November 1st and 2nd to coincide with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ day in the Christian calendar, and honours the spirits of the deceased. -

God of the Month: Tlaloc

God of the Month: Tlaloc Tlaloc, lord of celestial waters, lightning flashes and hail, patron of land workers, was one of the oldest and most important deities in the Aztec pantheon. Archaeological evidence indicates that he was worshipped in Mesoamerica before the Aztecs even settled in Mexico's central highlands in the 13th century AD. Ceramics depicting a water deity accompanied by serpentine lightning bolts date back to the 1st Tlaloc shown with a jaguar helm. Codex Vaticanus B. century BC in Veracruz, Eastern Mexico. Tlaloc's antiquity as a god is only rivalled by Xiuhtecuhtli the fire lord (also Huehueteotl, old god) whose appearance in history is marked around the last few centuries BC. Tlaloc's main purpose was to send rain to nourish the growing corn and crops. He was able to delay rains or send forth harmful hail, therefore it was very important for the Aztecs to pray to him, and secure his favour for the following agricultural cycle. Read on and discover how crying children, lepers, drowned people, moun- taintops and caves were all important parts of the symbolism surrounding this powerful ancient god... Starting at the very beginning: Tlaloc in Watery Deaths Tamoanchan. Right at the beginning of the world, before the gods were sent down to live on Earth as mortal beings, they Aztecs who died from one of a list of the fol- lived in Tamoanchan, a paradise created by the divine lowing illnesses or incidents were thought to Tlaloc vase. being Ometeotl for his deity children. be sent to the 'earthly paradise' of Tlalocan. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

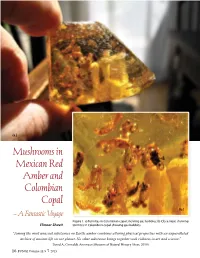

“Among the Most Unusual Substances on Earth, Amber Combines Alluring Physical Properties with an Unparalleled Archive of Ancient Life on Our Planet

(a.) (b.) Figure 1. a) Termites in Colombian copal showing gas bubbles; b) Close view, showing termites in Colombian copal showing gas bubbles. “Among the most unusual substances on Earth, amber combines alluring physical properties with an unparalleled archive of ancient life on our planet. No other substance brings together such richness in art and science.” David A. Grimaldi, American Museum of Natural History (Ross, 2010) 16 FUNGI Volume 11:5 2019 Figure 2. A rough piece of blue Dominican amber. y quest for mushrooms in Mushroom lovers were treated to a and so versatile. As a gemologist, amber amber and copal lasted about small, extremely rare piece of light- was an organic, semi-precious gemstone a decade, from the mid-1990s colored amber, inside which a tiny gilled for me, soft for a gemstone (only 2-2.5 Mto the early part of the 2000s. During mushroom was barely visible. Through on the Mohs scale), and with multiple this period of time, I found mushrooms a strategically placed magnifying glass, places of origin around the world. It in Mexican red amber from Chiapas, excited visitors could get a glimpse of came in multiple colors, and lended itself and in Colombian copal from the what the ancestor of today’s Mycena to carving and the creation of beautiful Santander region; these pieces make up looked like, down to its cap, delicate works of art. As a mycologist seeking the bulk of my collection. The unique gills, and stipe. Though an extinct mushrooms inside the amber, amber fossils of mushrooms, amber, and copal species and millions of years old, the was the fully polymerized tree resin that in this collection are still waiting to be fossilized mushroom looked fresh and formed millions of years ago in what studied. -

Imitation Amber Beads of Phenolic Resin from the African Trade

IMITATION AMBER BEADS OF PHENOLIC RESIN FROM THE AFRICAN TRADE Rosanna Falabella Examination of contemporary beads with African provenance reveals large quantities of imitation amber beads made of phenol- formaldehyde thermosetting resins (PFs). This article delves into the early industrial history of PFs and their use in the production of imitation amber and bead materials. Attempts to discover actual sources that manufactured imitation amber beads for export to Africa and the time frame have not been very fruitful. While evidence exists that PFs were widely used as amber substitutes within Europe, only a few post-WWII references explicitly report the export of imitation amber PF beads to Africa. However they arrived in Africa, the durability of PF beads gave African beadworkers aesthetic freedom not only to rework the original beads into a variety of shapes and sizes, and impart decorative elements, but also to apply heat treatment to modify colors. Some relatively simple tests to distinguish PFs from other bead materials are presented. Figure 1. Beads of phenol-formaldehyde thermosetting resins INTRODUCTION (PFs) from the African trade. The large bead at bottom center is 52.9 mm in diameter (metric scale) (all images by the author unless otherwise noted). Strands of machined and polished amber-yellow beads, from small to very large (Figure 1), are found today in the He reports that other shapes, such as barrel and spherical stalls of many African bead sellers as well as in on-line (Figure 2), were imported as well, but the short oblates stores and auction sites. They are usually called “African are the most common. -

157. Templo Mayor (Main Temple). Tenochtitlan (Modern Mexico City, Mexico)

157. Templo Mayor (main Temple). Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico City, Mexico). Mexica (Aztec). 1375-1520 C.E. Stone (temple); volcanic stone (The Coyolxauhqui Stone); jadeite (Olmec-style mask); basalt (Calendar Stone). (4 images) dedicated simultaneously to two gods, Huitzilopochtli, god of war, and Tlaloc, god of rain and agriculture, each of which had a shrine at the top of the pyramid with separate staircases 328 by 262 ft) at its base, dominated the Sacred Precinct rebuilt six times After the destruction of Tenochtitlan, the Templo Mayor, like most of the rest of the city, was taken apart and then covered over by the new Spanish colonial city After earlier small attempts to excavate - the push to fully excavate the site did not come until late in the 20th century. On 25 February 1978, workers for the electric company were digging at a place in the city then popularly known as the "island of the dogs." It was named such because it was slightly elevated over the rest of the neighborhood and when there was flooding, street dogs would congregate there. At just over two meters down they struck a pre-Hispanic monolith. This stone turned out to be a huge disk of over 3.25 meters (10.7 feet) in diameter, 30 centimeters (11.8 inches) thick and weighing 8.5 metric tons (8.4 long tons; 9.4 short tons). The relief on the stone was later determined to be Coyolxauhqui, the moon goddess, dating to the end of the 15th century o From 1978 to 1982, specialists directed by archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma worked on the project to excavate the Temple.[5] Initial excavations found that many of the artifacts were in good enough condition to study.[7] Efforts coalesced into the Templo Mayor Project, which was authorized by presidential decree.[8] o To excavate, thirteen buildings in this area had to be demolished. -

Save/View This Catalog in PDF Format

H O W A R D N O W E S A N C I E N T A R T www.howardnowes.com - 6 - www.howardnowes.com www.howardnowes.com HOWARD NOWES ANCIENT ART ANCIENT ART & ARTIFACTS Volume III, No. 2 Winter 2001 $5.00 Welcome to this Holiday edition of GALLERY SERVICES Ancient Art & Artifacts. This catalog contains Let us sell your antiquities! We can an excellent range of sculpture and ceramics, sell your collections in our gallery, through each piece chosen for their uniqueness and direct mail or at public auction, where the competitive bidding enviornment can be eye appeal. Objects are easily viewable in full suprisingly benificial. color online at www.howardnowes.com where condition reports are also available. If We offer restoration & conservation, which is preformed by trained professionals in New York City, please call to schedule an with more the 20 years experience. appointment for a viewing in person. We Go on-line to art-restoration.net for full recommend that you check the availability of details. items to avoid disappointment. Custom mounting is done by an 5 2 experience talented artist with more then 25 TERMS OF SALE years of experience. We offer appraisals for insurance pur- All items offered are unique and pouses and can help you with the valuation of subject to prior sale. Prices are in US dollars. objects. Just send us clear photos with sizes and 4 All sales are accompanied by a typed invoice, condition and follow up with a phone call. signed by our director, with all the relevant collection and provenance information. -

Curandera's Altar

5/16/2019 RUE, RESIN AND ROSE: SACRED AND MEDICINAL TRILOGY OF LATIN AMERICAN M A T E R I A MEDICA Mimi Hernandez, MS, RH(AHG) CURANDERA’S ALTAR 1 5/16/2019 RUE RUE 2 5/16/2019 SACRED RESINS 3 5/16/2019 RUE An herb of grace allowing us to screen out negative influences and clearly visualize and manifest our visionary potential. RUE At one time the holy water was sprinkled from brushes made of Rue at the ceremony usually preceding the Sunday celebration of High Mass, for which reason it is supposed it was named the Herb of Repentance and the Herb of Grace. 4 5/16/2019 RUE The fibrous roots of this herb reminded some people of the blood vessels in the eye, which may account for its use as an eyestrain treatment. Rue was once believed to improve the eyesight and creativity, and no less personages than Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci regularly ate the small, trefoil leaves to increase their own. RUE Rue is also used to give a person “second sight” and was believed to help see into the future. A potent remedy to ward off the “evil eye” or “mal ojo” 5 5/16/2019 RUE Also commonly known as the Herb of Fair Maidens in France, Rue has long been a symbol of virtue and purity. As part of traditional Lithuanian wedding rites, the bride wears a crown of Rue which is burned during the ceremony to symbolize her transition from the whimsy and virtue of childhood to the responsibilities of motherhood and adulthood. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of MEXICO the Classic Period to the Present

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MEXICO The Classic Period to the Present Created by Steve Maiolo Copyright 2014 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Section 1: The Maya The Mayan Creation Myth ........................................................................ 1 Ollama ..................................................................................................... 1 Mayan Civilization Social Hierarchy ....................................................................................... 2 Religion ................................................................................................... 3 Other Achievements ................................................................................ 3 The Decline of the Mayans ...................................................................... 3 Section 2: The Aztecs The Upstarts ............................................................................................ 4 Tenochtitlàn ............................................................................................. 4 The Aztec Social Hierarchy Nobility (Pipiltin) ....................................................................................... 5 High Status (not nobility) .......................................................................... 5 Commoners (macehualtin) ....................................................................... 6 Slaves ...................................................................................................... 6 Warfare and Education ........................................................................... -

Aztec Festivals of the Rain Gods

Michael Graulich Aztec Festivals of the Rain Gods Aunque contiene ritos indiscutiblemente agrícolas, el antiguo calendario festivo de veintenas (o 'meses') de la época azteca resulta totalmente desplazado en cuanto a las temporadas, puesto que carece de intercalados que adaptan el año solar de 365 días a la duración efectiva del año tropical. Creo haber demostrado en diversas pu- blicaciones que las fiestas pueden ser interpretadas en rigor sólo en relación con su posición original, no corrida aún. El presente trabajo muestra cómo los rituales y la re- partición absolutamente regular y lógica de las vein- tenas, dedicadas esencialmente a las deidades de la llu- via - tres en la temporada de lluvias y una en la tempo- rada de sequía - confirman el fenómeno del desplaza- miento. The Central Mexican festivals of the solar year are described with consi- derable detail in XVIth century sources and some of them have even been stu- died by modern investigators (Paso y Troncoso 1898; Seler 1899; Margain Araujo 1945; Acosta Saignes 1950; Nowotny 1968; Broda 1970, 1971; Kirchhoff 1971). New interpretations are nevertheless still possible, especially since the festivals have never been studied as a whole, with reference to the myths they reenacted, and therefore, could not be put in a proper perspective. Until now, the rituals of the 18 veintenas {twenty-day 'months') have always been interpreted according to their position in the solar year at the time they were first described to the Spaniards. Such festivals with agricultural rites have been interpreted, for example, as sowing or harvest festivals on the sole ground that in the 16th century they more or less coincided with those seasonal events. -

2 REMARKS on a NAHUATL HYMN Xippe Ycuic, Totec. Yoallavama

N68 IV : 2 REMARKS ON A NAHUATL HYMN Xippe ycuic, totec. Yoallavama. Yoalli tlavana, yztleican timonenequia, xiyaquimitlatia teucuitlaque- mitl, xicmoquentiquetl ovia. Noteua, chalchimamatlaco apanaytemoaya, ay, quetzalavevetl, ay quetzalxivicoatl. Nechiya, yquinocauhquetl, oviya. Maniyavia, niavia poliviz, niyoatzin. Achalchiuhtla noyollo; a teu- cuitlatl noyolcevizqui tlacatl achtoquetl tlaquavaya otlacatqui yautla- toaquetl oviya. Noteua, ce intlaco xayailivis conoa yyoatzin motepeyocpa mitzalitta moteua, noyolcevizquin tlacatl achtoquetl tlaquavaya, otlacatqui yau- tlatoaquetl, oviya. —so runs an ancient Mexican hymn to the god Xipe Totec, preserved in a manuscript of the 1580's when the memory of the old faith had not been far submerged beneath the Christian. It was, however, of a far older date than the generation which saw the Conquest. By even that time the meaning had become so obscure through alteration of the language that it required a marginal gloss, which will aid us in 1 This study was found among the late R. H. Barlow's unpublished papers, now preserved at the University of the Americas. The work possibly dates back as early as 1943.44, when he first began to study Náhuati literature. It seems to be typical of his early style, more imagina- tive, less reserved, than his later, more scholarly, manner of writing. It is evident that Barlow had planned to re-write the study in later years. On the first page the following pencil-written words appear: "This would have to be revised some if you're interested. R.H.B." On the back of the last leaf the following criticism (not in the author's handwriting) may be read: "Was the poem the work of 'a poet'? Should be asked if not answered.