Design and Implementation of a Novel Web-Based E-Learning Tool for Education of Health Professionals on the Antibiotic Vancomycin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Aims Methods Results Conclusions

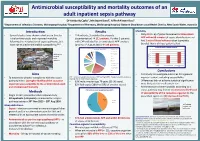

Antimicrobial susceptibility and mortality outcomes of an adult inpatient sepsis pathway Dr Kimberly Cipko1, Mr Stuart Bond2, A/Prof Alistair Reid1 1Department of Infectious Diseases, Wollongong Hospital; 2Department of Pharmacy, Wollongong Hospital, Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, New South Wales, Australia Introduction Results Mortality • Several studies have shown reductions in time to • 114 patients, 3 excluded (inadequate • Only 6% (n=6) of patients received antimicrobials initial antimicrobials and improved mortality documentation) 111 patients. Further 5 patients APP within 60 minutes of sepsis identification and following the introduction of sepsis pathways, but with CAP excluded for ‘antimicrobials APP’ analysis had 2 sets of blood cultures taken (complete have not studied antimicrobial susceptibility.1,2,3 (prior to 1st August 2016) 106 patients. bundle). None of those patients died. 30-day all-cause in hospital mortality Source of sepsis (%) Unkown origin 35 HAP low MRO 30 4 111 25 Wollongong 6 HAP high MRO 20 Hospital 5 CAP 33 15 NSW, Urine % mortality % mortality 10 Australia 9 Biliary/GI 5 Skin/surgical site 0 5 Diabetic foot Overall Antimicrobials APP Antimicrobials not APP Peri/postpartum 13 Other 23 Conclusions Neuro Aims • First study to investigate outcomes for a general CAP – community acquired pneumonia; HAP low/high MRO – Hospital acquired pneumonia inpatient cohort, including susceptibility. • To determine whether compliance with the sepsis low/high risk of multi-resistant organisms pathway led to: (1) Higher likelihood the causative • 63% male; median age 76 years (21-96 years). • Differences did not achieve statistical significance – organism was susceptible to the antimicrobials used • 82% had sepsis (18% had SIRS of another cause). -

Masterplan LAND ESTATE W

EDUCATION 1 The Little School Pre School 2 min 1km 2 Dapto Public School 8 min 7km 3 Mount Kembla Public School 15 min 12.6km 4 Kanahooka High School 7 min 5.8km 5 Illawarra Sports High School 10 min 9.2km 6 Dapto High School 9 min 6.3km 7 Five Islands Secondary College 18 min 4.6km 8 University of Wollongong 13 min 15.1km 9 TAFE Illawarra Wollongong Campus 14 min 15.7km RETAIL 1 Wollongong Central 15 min 14.9km 2 Figtree Grove Shopping Centre 11 min 10.1km 3 Dapto Mall 5 min 4.9km 4 Shellharbour Village 22 min 21.3km 5 Shellharbour Square Shopping Centre 22 min 18.5km 6 Shell Cove 20 min 20km (with Marina under construction) HEALTH 1 Wollongong Hospital 13 min 14km 2 Wollongong Private Hospital 13 min 13.7km 3 Dapto Medical Centre 5 min 4.9km 4 Illawarra HealthCare Centre 4 min 3.8km 5 Illawarra Medical Services 9 min 8.4km 6 Illawarra Area Health Service 15 min 15.4km 7 Lotus Wellbeing Centre 18 min 16.6km RECREATION 1 Kembla Grange Racecourse 5 min 4.5km 2 Fox Karting Centre 5 min 4.9km 3 The Grange Golf Club 6 min 5.3km 4 Ian McLennan Park 5 min 4.8km 5 Berkeley Youth & Recreation Centre 9 min 7.8km 6 Wollongong Surf Leisure Resort 16 min 19.5km 7 Windang Bowling Club 19 min 18.1km 8 Lake Illawarra Yacht Club 11 min 10.5km 9 Port Kembla Beach 16 min 16km 10 WIN Stadium 16 min 16km 11 WIN Entertainment Centre 17 min 16.9km 12 Jamberoo Action Park 22 min 20.7km 13 Wollongong Golf Club 18 min 17km 14 Killalea State Park 23 min 21.7km TRANSPORT 1 Kembla Grange Train Station 4 min 4.2km 2 Dapto Train Station 6 min 5.1km 3 Unanderra Train Station 9 min 8km 4 Coniston Train Station 14 min 15.1km 5 Wollongong Train Station 16 min 16.5km Stockland Shellharbour Shopping Centre University of Wollongong Nan Tien Temple City of Wollongong Proudly marketed by: Simon Hagarty - Sales Manager REGISTER HERE: C 0405 175 416 BRAND NEW E [email protected] Masterplan LAND ESTATE www.KemblaGrangeEstate.com.au W www.ulh.com.au Disclaimer: This is a sales plan only. -

Illawarra & Shoalhaven Sexual Health & Blood Borne Infections Directory

Illawarra & Shoalhaven Sexual Health & Blood Borne Infections Directory Intention of the directory: What is sexual health? According to the World Health Organisation sexual health is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity, but rather, sexual health includes a holistic state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being. As such, sexual health requires a respectful approach to sexuality and relationships, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Who is HARP? The HARP Health promotion team promote prevention, early intervention, treatment and management of HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C and Sexually Transmitted Infections. The HIV and Related Programmes Unit (HARP) activity is guided by National, State and Local Health District strategies that aims to improve sexual health and reduce the harm associated with Sexually Transmissible Infections (STIs), HIV and Hepatitis C. The HARP team partner with community organisations who engage and represent people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD), young people, Aboriginal people, sex workers, gay men, men who have sex with men (MSM), people living with HIV, people who inject drugs, and heterosexuals with a recent change in partner. HARP provide a range of free resources, work in collaboration with partner organisations on projects and develop awareness raising and capacity building training sessions. What is the intention of HARP? Our intention is to create a positive environment in which the community feel comfortable to approach the issues of HIV, STIs and Blood Borne Infections (BBIs) and acknowledge the realities of their impact both within our own communities and globally. We work towards creating an environment where HIV, STIs and BBIs can be discussed, accepted and ultimately prevented without fear, myth, stigma or discrimination. -

Feasibility of a Multi-Generational Birth Cohort Study Michelle L

Townsend et al. Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2019) 5:32 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0418-5 STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Illawarra Born cross-generational health study: feasibility of a multi-generational birth cohort study Michelle L. Townsend1,2, Megan A. Kelly1,7, Judy A. Pickard1,2, Theresa A. Larkin1,3, Victoria M. Flood5,6, Peter Caputi1,2, Ian M. Wright1,3,4, Alison Jones1,3 and Brin F. S. Grenyer1,2* Abstract Background: There is a strong interest in the concept of developmental origins of health and disease and their influence on various factors “from cradle to grave”. Despite the increasing appreciation of this lifelong legacy across the human life course, many gaps remain in the scientific understanding of mechanisms influencing these formative phases. Cross-generational susceptibility to health problems is emerging as a focus of research in the context of birth cohort studies. The primary aim of the Illawarra Born study is to make scientific discoveries associated with improving health and wellbeing across the lifespan, with a particular focus on preventable chronic diseases, especially mental health. This birth cohort study will follow and collect data from three cohorts representing different stages across the lifespan: infants, adults (parents) and older adults (grandparents). The multi-generational, cross-sectional and longitudinal design of this birth cohort study supports a focus on the contributions of genetics, environment and lifestyle on health and wellbeing. The feasibility of conducting a multi-generational longitudinal birth cohort project was conducted through a small pilot study. Methods/design: The purpose of this paper is to report on the feasibility and acceptability of the research protocol for a collaborative cross-generation health study in the community and test recruitment and outcome measures for the main study. -

Wollongong Hospital Nurses' Home

Wollongong Hospital Nurses’ Home Heritage Significance Assessment Final Report Report prepared for NSW Health Infrastructure September 2011 Report Register The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Wollongong Hospital Nurses’ Home—Heritage Significance Assessment, undertaken by Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system. Godden Mackay Logan operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008. Job No. Issue No. Notes/Description Issue Date 10-0466 1 Draft Report June 2011 10-0466 2 Final Report September 2011 Copyright Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced at the end of each section and/or in figure captions. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners. Unless otherwise specified or agreed, copyright in this report vests in Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd (‘GML’) and in the owners of any pre-existing historic source or reference material. Moral Rights GML asserts its Moral Rights in this work, unless otherwise acknowledged, in accordance with the (Commonwealth) Copyright (Moral Rights) Amendment Act 2000. GML’s moral rights include the attribution of authorship, the right not to have the work falsely attributed and the right to integrity of authorship. Right to Use GML grants to the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title) an irrevocable royalty-free right to reproduce or use the material from this report, except where such use infringes the copyright and/or Moral Rights of GML or third parties. -

Free Gong Shuttle Saved! Thanks to You Wollongong, Together We Have Saved the Gong Shuttle

JULY 2018 JULY PAUL SCULLY’S WOLLONGONG WRAP UP Office & Mail: Suite 2S, Rear Ground Floor, 111 Crown Street, Wollongong, NSW 2500 Phone: (02) 4226 5700 Fax: (02) 4226 9963 Web: paulscullymp.com.au paulscullymp Email: [email protected] PaulScullyWollongong Free Gong Shuttle saved! Thanks to you Wollongong, together we have saved the Gong Shuttle. We signed petitions and held a public rally in the Wollongong Mall, to tell the Berejiklian Government just what we all thought of its plan to introduce Opal fares on the free Gong Shuttle service. After months of hard work and negotiations, an agreement has finally been reached where the Gong Shuttle will remain free and continue to operate 7 days a week on its existing routes, which includes stops at the University of Wollongong, Innovation Campus, Wollongong CBD and Wollongong Hospital. There will be minor changes to the timetable on Sundays and public holidays. On these days, Gong Shuttle services will run between 9.40am and 5.20pm, instead of starting at 8am and finishing at 6pm. Buses will continue to run every 20 minutes. The agreement between Transport for NSW, the University of Wollongong and Wollongong City Council makes sure that the Gong Shuttle service remains free. Does the NSW Government have some of your money? There’s more than $380 million of your money, waiting to be claimed from deceased estates, dividends, bonds and overpayments, according to Revenue NSW. So what are you waiting for? Go to www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/ucm/search to see if any of the unclaimed money is yours. -

Port Kembla Berth 103, Stage 2 Development Project

PORT KEMBLA BERTH 103, STAGE 2 DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Total # of Pages 34 DOCUMENT COVER SHEET (incl. Doc Cover Sheet) Proponent Document No Revision No Document Title Emergency Response Plan Enquiry/Contract/Order No NSWP 2013-05 (Purchase Order – PO000527-1) Scope Dredging and Spoil Disposal Works CONTRACTOR Document 036-10211-02-004 Contractors Rev No 02 No CONTRACTOR shall ensure that Prepared D. Inger Checked L. Barratt Approved C. Tombolato documents have been fully checked and approved prior to submittal to Proponent. Date 22/12/2014 Date 23/12/2014 Date 23/12/2014 CONTRACTOR Name, Address and Notes: Logo Boskalis Australia Pty Ltd Suite 802, Tower A, Zenith Centre 821 Pacific Highway, Chatswood NSW, 2067 02 13.06.2015 Updated with EPL Requirements 01 22.12.2014 Initial plan for comment REV DATE ISSUE PURPOSE No Revision History to Company’s Document Number Berth 103 Stage 2 Extension - Dredging and Spoil Disposal Works Emergency Response Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. DEFINITIONS & ABBREVIATIONS 4 1.1 Definitions 4 1.2 Abbreviations 5 2. PROJECT INTRODUCTION 6 2.1 General 6 2.2 Project Overview 6 2.3 Purpose and Applicability 8 3. REFERENCES 9 3.1 Controlled Legislation 9 3.2 Codes of Practice and Standards 9 3.3 PROPONENT Documents 9 3.4 CONTRACTOR Documents 10 3.5 PROJECT Documents 11 4. EMERGENCY RESPONSE - OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS 12 4.1 Management Objectives 12 4.2 Targets 12 5. EMERGENCY RESPONSE ORGANISATION AND RESPONSIBILITIES 13 5.1 Crisis Manager (CM) 13 5.2 Incident Controller (IC) 13 5.3 Emergency Response Team (ERT) 14 5.3.1 Emergency Drills 14 6. -

Checklist for SSA Submissions to The

Checklist for Site Specific Assessment submissions to the Research Governance Officer Site Specific Assessments (SSA) can be submitted before or after receiving Ethics approval, however both submissions are encouraged to be done in parallel. Please include 1 copy of each of the documents submitted for Research Ethics Approval and 1 original of the following documents: Cover Letter: Outline if study has been or is being considered by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) Identify if HREC approval has been granted (include date) or is pending If available, include the HREC reference number List all documents enclosed Site Specific Assessment Form (SSA) – www.ethicsform.org/au Signed and dated by ALL investigators named in the SSA Signed by the relevant ISLHD Head(s) of Department(s) – Principal Investigators who are Heads of Department must not sign their own SSA applications but must obtain the signature of their direct manager. Signed by relevant ISLHD Head(s) of Supporting Department(s) (eg. Pharmacy if dispensing drugs) (if applicable) Signed by Data Provision (if applicable) Documents to be included with the SSA submission: Short CV for all Investigators (Principal and Associate) named in the SSA form Site Specific Participant Information Sheet and Consent Form (must include the ISLHD logo and each page must have the date and version number in the footer) Letter of approval from the HREC HREC Amendment Approval Letters (if applicable) National Ethics Application Form (NEAF) or Low/Negligible Risk Ethics Application -

Message from the Dean

Issue 4 August to October - 2012 Message from the Dean As we all know China is a power house of the world’s economy and Australia’s leading trading partner. Even regular visitors to China are continually astounded at the rate and quality of China’s advancement. It seems that every few months China’s landscape visibly changes as it improves the living standards of its vast population by developing and implementing technologies and infrastructure to provide energy, water, housing, health, transport and other services that many other countries take for granted, but which in China have only recently become practically available on a large scale. The energy, creativity and dynamism required to implement such massive change is immense, but Chinese Universities, Industries and Central and Provincial Governments are determinedly rising to these challenges. Welcome to the Engineering Comprehending the scale of China’s achievements and ambitions is not an easy matter. China has to build about 4 United States of America’s to offer its newsletter for 2012 population a similar standard of living as in USA. In 2010, Chinese expenditure Featured in this issue: on research and development was over $US149 billion and some estimates for 2012 suggest it will be $US199 billion. This will be greater than Germany, . Editorial France and the UK combined. .Discover Engineering Day .Canadian Geotechnical Award Australia is well placed to partner with China in R&D. At a recent China- .CESE2012 Australian alumni celebration I attended in Shanghai a few weeks ago, attended .CME Student Success by over 300 Chinese born graduates of Australian Universities, it was clear that .Between a rock and a hard place there was tremendous goodwill towards Australia from these very high .Race In2Uni achieving people across all walks of Industry, Commerce, Government, Science .IRMMW‐THZ 2012 and Engineering. -

1925 Greens Cunningham 6.Indd

CUNNINGHAM NEWS Newsletter of the Federal Member for Cunningham, Michael Organ MP New Office - Globe Lane Wollongong ISSUE 6 JUNE 2004 Web - www.michaelorgan.org.au IN THIS NEWSLETTER • Federal Budget BUDGET PROVIDES • Employment • Lower East Crown Street • Industrial Manslaughter SLIM PICKINGS FOR • Royal Commission • Global Warming THE ILLAWARRA • ATSIC Rally Treasurer Peter Costello’s latest budget lending right scheme which will allow • Port Kembla Expansion is a lost opportunity for the community local authors to continue to receive • Superannuation with tax cuts favoured over urgent royalty payments when their books spending needs in health care and are borrowed from public libraries. • 50th Wedding Anniversary job creation for the Illawarra and is We should also be expecting to receive nothing more than old-fashioned, pre- • ‘Oilies’ Surfing Spot a slice of the $45 million per year election pork-barrelling tagged for accident black spots to be • Bulli Hospital The government’s decision to allocate spent on the Princes Highway. Emergency Department a paltry $7.2M over 4 years for the With the imminent release of the continuation of the voluntary work • Sports Awards government’s Auslink white paper, initiative program is a far cry from a the jury is still out on the prospect of • May Day job creation scheme the community federal funding to expand Port Kembla has been asking for by anyone’s and its rail links. • Medical Retrieval Unit measure. Overall this budget provides slim • Public Education The would-be PM, Treasurer Peter pickings for the Illawarra. • Inviting Michael to Functions Costello, is continuing to turn a blind- eye to the unemployment crisis in the The Government’s decision to only • Constituent News Illawarra. -

Related Presentations in an Australian Teaching Hospital Siyu Qian University of Wollongong, Illawarra and Shoalhaven Local Health District, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online University of Wollongong Masthead Logo Research Online Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 2019 Investigating the management of alcohol‐related presentations in an Australian teaching hospital Siyu Qian University of Wollongong, Illawarra and Shoalhaven Local Health District, [email protected] Mudar Irani Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Renee M. Brighton University of Wollongong, [email protected] Wilfred W. Yeo University of Wollongong, Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, [email protected] David Reid Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, Drug And Alcohol Service See next page for additional authors Publication Details Qian, S., Irani, M., Brighton, R., Yeo, W., Reid, D., Sinclair, B., Bresnahan, S., Lynch, P., Feng, X. & Yu, P. (2019). Investigating the management of alcohol‐related presentations in an Australian teaching hospital. Drug and Alcohol Review, 38 (2), 190-197. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Investigating the management of alcohol‐related presentations in an Australian teaching hospital Abstract Introduction and Aims: Alcohol‐related morbidity is estimated to range from 10-38% of the presentations to hospital emergency departments. This study aims to investigate the actual management process for alcohol‐related presentations in a teaching hospital in Australia. Design and Methods: Retrospective audit was conducted on the electronic medical records of 210 presentations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of 'alcohol use disorder' at discharge between November 2016 and February 2017. -

The Illawarra Shoalhaven Health Care System

Working Together Building Healthy Futures The Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health Care Services Plan 2012-2022 October 2012 Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health Care Services Plan 2012–2012 Locked Bag 8808 SOUTH COAST MAIL CENTRE NSW 2521 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part to inform people about the strategic directions for health care services in the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, and for study and training purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. It may not be reproduced for commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires written permission from the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District. Website: http://www.islhd.health.nsw.gov.au/ Prepared by the Planning Team - part of the Planning, Performance and Redesign Unit, Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District. For further information, please contact the Planning Team on (02) 4221 6710. i Our Health Care Services Plan 2012-2022 FOREWORD WORKING TOGETHER BUI LDING HEALTHY FUTURE S Our Health Care Services Plan 2012 to 2022 “Working Together Building Healthy Futures” sets out an ambitious vision for the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District’s future health service delivery. It clearly articulates the reform areas we need to focus on if we are to create a sustainable and integrated service system for the future. The Plan provides direction for the development of our health care service over the next ten years, building on our successes and creating a platform for continuous improvement that will lay firm foundations for excellence in service delivery for many years to come.