(Hint: the Films Are) Disney Channel Franchises &A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Disney Letar Ny Stjärna I Sverige

Disney letar ny stjärna i Sverige I höst är det premiär för ungdomsserien Violetta på Disney Channel i Sverige. Tv-serien har på kort tid etablerat sig som ett ungdomsfenomen på flera internationella marknader där programmets musik spelas flitigt även utanför tv-rutan. Inför premiären i Sverige söker Disney nu tillsammans med Universal MusiC oCh Spinnup en lokal talang för att spela in seriens svenska ledmotiv. Tv-serien Violetta följer huvudpersonen med samma namn i allt det som hör tonårstiden till; kompisar, kärlek, familj och drömmar om framtiden. En stor del av historien utspelar sig på den sång- och dansskola som ’Violetta’ går på och musik är en integrerad del i berättelsen där varje avsnitt innehåller flera specialskrivna låtar. - Det känns fantastiskt roligt att Violetta snart kommer hit. Efter succéerna med Hannah Montana och High School Musical har vi väntat på nästa serie med lika stor potential och att döma av vad vi sett på andra marknader har vi nu det i Violetta. I ett sådant sammanhang känns det extra kul att kunna vidareutveckla vårt samarbete med Universal Music för att hitta rätt sångtalang, säger Anna Glanmark, Marknadsdirektör, The Walt Disney Company Nordic. Arbetet med att identifiera rätt talang för det svenska ledmotivet görs i samarbete med Universal Music genom Spinnup som är en digital distributionstjänst för osignade artister. Det som gör Spinnup unikt är att de osignade artisterna som distribuerar sin musik via tjänsten har tillgång till ett dedikerat team av Spinnup Scouter som söker nya talanger att jobba med, nu även med fokus att hitta Disneys nya stjärna. -

On the Disney Channel's Hannah Mont

Tween Intimacy and the Problem of Public Life in Children’s Media: “Having It All” on the Disney Channel’s Hannah Montana Tyler Bickford Contradictions of public participation pervade the everyday lives of con- temporary children and those around them. In the past two decades, the children’s media and consumer industries have expanded and dramat- ically transformed, especially through the development and consolida- tion of “tweens”—people ages nine to thirteen, not yet “teenagers” but no longer quite “children”—as a key consumer demographic (Cook and Kaiser 2004). Commentators increasingly bemoan the destabilization of age identities, pointing to children’s purportedly more “mature” taste in music, clothes, and media as evidence of a process of “kids getting older younger” (Schor 2004), and to adults’ consumer practices as evidence of their infantilization (Barber 2007). Tween discourses focus especially on girls, for whom the boundary between childhood innocence and adolescent or adult independence is fraught with moral panic around sexuality, which only heightens anxieties about changing age identities. Girls’ consumption and media participation increasingly involve per- formances in the relatively public spaces of social media, mobile media, and the Internet (Banet-Weiser 2011; Bickford, in press; Kearney 2007), so the public sphere of consumption is full of exuberant participation in mass-mediated publics. Beyond literal performances online and on social media, even everyday unmediated consumption—of toys, clothes, food, and entertainment—is fraught with contradictory meanings invoking children’s public image as symbols of domesticity, innocence, and the family and anxiety about children’s intense affiliation with peer com- munities outside the family (Pugh 2009). -

Tv Guide Pg1b 9-27.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, Sept. 27, 2011 1b All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening September 27, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 ABC 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark Dancing With Stars Body of Proof Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles Unforgettable Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD FOX Glee New Girl Raising Local 2 PBS KOOD 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land 23 ESPN 2 47 Food Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Wars Local 4 ABC-KLBY AMC The Mummy The Mummy Local 5 KSCW WB 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM Madagascar River Monsters Madagascar Local 6 ABC-KLBY 6 Weather BET 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV Preacher's Kid The Perfect Man Wendy Williams Show Prchr Kid Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Rachel Zoe Project Rachel Zoe Project Rachel Zoe Project Rachel Zoe Project Most Eligible Dallas 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Extreme Makeover Grumpier Old Men Angels 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 John King, USA Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Local 35 NFL 64 Oxygen 9 Eagle COMEDY Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Work. -

Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000S

SECRET SUPERSTARS AND OTHERWORLDLY WIZARDS: Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000s By © 2017 Christina H. Hodel M.A., New York University, 2008 B.A., California State University, Long Beach, 2006 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Germaine Halegoua, Ph.D. Joshua Miner, Ph.D. Catherine Preston, Ph.D. Ronald Wilson, Ph.D. Alesha Doan, Ph.D. Date Defended: 18 November 2016 The dissertation committee for Christina H. Hodel certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: SECRET SUPERSTARS AND OTHERWORLDLY WIZARDS: Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000s Chair: Germaine Halegoua, Ph.D. Date Approved: 25 January 2017 ii ABSTRACT Conformity messaging and subversive practices potentially harmful to healthy models of feminine identity are critical interpretations of the differential depiction of the hiding and usage of tween girl characters’ extraordinary abilities (e.g., super/magical abilities and celebrity powers) in Disney Channel television sitcoms from 2001-2011. Male counterparts in similar programs aired by the same network openly displayed their extraordinariness and were portrayed as having considerable and usually uncontested agency. These alternative depictions of differential hiding and secrecy in sitcoms are far from speculative; these ideas were synthesized from analyses of sitcom episodes, commentary in magazine articles, and web-based discussions of these series. Content analysis, industrial analysis (including interviews with industry personnel), and critical discourse analysis utilizing the multi-faceted lens of feminist theory throughout is used in this study to demonstrate a unique decade in children’s programming about super powered girls. -

Disney (Movies)

Content list is correct at the time of issue DISNEY (MOVIES) 101 Dalmatians (1996) 101 Dalmatians Ii: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmatians 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Absent-Minded Professor, The Adventures Of Bullwhip Griffin, The Adventures Of Huck Finn, The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad, The African Cats African Lion, The Aladdin (1992) Aladdin (2019) Aladdin And The King Of Thieves Alexander And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Alice In Wonderland (1951) Alice In Wonderland (2010) Alice Through The Looking Glass Alley Cats Strike (Disney Channel) Almost Angels America's Heart & Soul Amy Annie (1999) Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The Apple Dumpling Gang, The Aristocats, The Artemis Fowl Atlantis: Milo's Return Atlantis: The Lost Empire Babes In Toyland Bambi Bambi Ii Bears Bears And I, The Beauty And The Beast (1991) Beauty And The Beast (2017) Beauty And The Beast-The Enchanted Christmas Bedknobs And Broomsticks (Not In Luxembourg) Bedtime Stories Belle's Magical World (1998) Benji The Hunted Beverly Hills Chihuahua Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3: Viva La Fiesta! Big Green, The Big Hero 6 Biscuit Eater, The Black Cauldron, The Content list is correct at the time of issue Black Hole, The (1979) Blackbeard's Ghost Blank Check Bolt Born In China Boy Who Talked To Badgers, The Boys, The: The Sherman Brothers' Story Bride Of Boogedy Brink! (Disney Channel) Brother Bear Brother Bear 2 Buffalo Dreams (Disney Channel) Cadet Kelly (Disney Channel) Can Of Worms (Disney Channel) Candleshoe Casebusters -

Central Times

Central Times Volume 4 No. 3 Central Times Staff Red Ribbon Week Charlie A. Josh B. By: Rebecca R. Will C. Central School has a Red Ribbon Week every year to Matt C. teach kids that drugs are bad for your mind and your Bob H. body. Central has students dress up in different ways Kelvin H. that represent why you shouldn’t do drugs. On Monday students dressed in Shelby J. sweats (being drug free is no sweat!), on Tuesday students wore a hat (put a Jonathan K. cap on drugs!), on Wednesday students wore their favorite team shirt (team Dylan K. up against drugs), on Thursday students dressed in blue (drugs give you the Matthew K. blues) and on Friday students wore mismatched clothes (drugs and I don’t Eric K. mix). The advisory with the most participation wins a party. The snowflake Alex L. members also made posters. Ben L. But how did Red Ribbon week start? It all started with a man named Emma M. Spencer M. Enrique Camarena. He grew up in a dirt floored house and dreamed to one Will N. day make a difference. Camarena worked hard to go through college and then Erik P. served in the Marines. He decided to become a police officer and then joined Celeste P. the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. His mom didn’t want him to go. Rebecca R. He told her he went to make a difference. He was sent undercover to Emma R. Mexico to investigate a major drug cartel that Brian R. -

Illustration by Martha Rich

ILLUSTRATION BY MARTHA RICH 50 SEPT | OCT 2009 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE By Robert Strauss Mixing up-to-the-minute marketing techniques, tried-and-true entertainment formulas, and engaging young stars and stories, Disney Channels Worldwide President Richard Ross C’83 is helping ensure that the company remains supreme in the kid-entertainment universe. her popular Disney Channel IN cable television show, Hannah Montana (if you live anywhere in the vicinity of a nine-year-old girl, you have surely seen it), Miley Cyrus plays a teenager with two identities— one as a famous rock star and the other as the daughter of a single fa- ther just trying to make it through what passes on TV for a normal life. Miley Stewart (Cyrus’s regular-girl identity) and her wacky older brother Jackson live in a Malibu beach house with their widowed father, played by Cyrus’s real-life father Billy Ray Cyrus, previously best known for his 1990s-era country music hit “Achy Breaky Heart.” The show’s comedy is a cheerful mix of teen misunderstandings and I Love Lucy slapstick revolving around Miley’s halfhearted efforts to keep her identities separate, with plenty of time left over for “Hannah” to perform her latest hit. CHANNELER THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE SEPT | OCT 2009 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE SEPT | OCT 2009 51 51 Since premiering on the Disney “That guy Ross” is Richard Ross C’83, entertainment phenomenon. Disney has Channel in March 2006, the series has president of Disney Channels Worldwide immediate name recognition for parents become a consistent top-rated show (a since April 2004, and an executive with and children, and the Disney Channel is new episode was the most watched cable the company since 1996. -

D-Signed for Girls: Disney Channel and Tween Fashion

1 Blue, Morgan G. (Final Draft: June 2013) Published with images in Film, Fashion & Consumption Special Issue: TV & Fashion, Ed. Helen Warner, volume 2, number 1 (2013). D-Signed for Girls: Disney Channel and Tween Fashion During the 2010 back-to-school retail season, the Walt Disney Company introduced the first in a growing collection of fashion lines for tween girls under the umbrella label D- Signed, available at Target stores throughout the United States. The initial line was based on the costumes of lead character Sonny Munroe of Sonny with a Chance (Marmel et al. 2009–2011), played by Demi Lovato. This was not Disney’s first foray into fashion for pre-teen and teen girl markets. Previous lines include a multitude of character licensing deals throughout Disney’s history and, more recently, a line inspired by Raven-Symoné’s character Raven Baxter of That’s So Raven (Poryes et al. 2003–2007), and fashion lines promoting Disney stars Miley Cyrus of Hannah Montana (Poryes and Peterman 2006– 2011) and Selena Gomez of Wizards of Waverly Place (Greenwald et al. 2007–2012) as designers, not to mention Hilary Duff’s independently produced fashion and consumer products collection, Stuff by Hilary Duff (2004). The introduction of the D-Signed collection, however, marks an unprecedented expansion of synergistic marketing strategies for comprehensive lifestyle branding to the tween girl market in the United States. The production and exponential growth of this particular fashion collection allow girls to literally (at Target stores or at home) and virtually (via sponsored online dress-up games and social networks) try on the ‘edgy’ fashions of Sonny Munroe, among other Disney Channel characters. -

Blue Crime “Shades of Blue” & APPRAISERS MA R.S

FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 9, 2018 5:07:40 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of June 16 - 22, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 6/30/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. Ray Liotta and Jennifer Lopez star in COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS Blue crime “Shades of Blue” & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 15 WATER STREET DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Det. Harlee Santos (Jennifer Lopez, “Lila & Eve,” 2015) and her supervisor, Lt. Matt The LawOffice of Wozniak (Ray Liotta, “Goodfellas,” 1990) will do all that they can to confront Agent STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Robert Stahl (Warren Kole, “Stalker”) and protect their crew, which includes Tess Naza- Auto • Homeowners rio (Drea de Matteo, “The Sopranos”), Marcus Tufo (Hampton Fluker, “Major Crimes”) 978.739.4898 Business • Life Insurance Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com and Carlos Espada (Vincent Laresca, “Graceland”), in the final season of “Shades of 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] Blue,” which premieres Sunday, June 17, on NBC. -

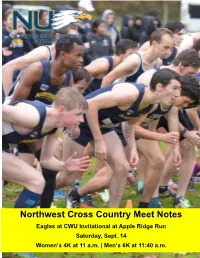

CWU XC INV. @ APPLE RIDGE RUN Sat

Northwest Cross Country Meet Notes Eagles at CWU Invitational at Apple Ridge Run Saturday, Sept. 14 Women’s 4K at 11 a.m. | Men’s 6K at 11:40 a.m. CWU XC INV. @ APPLE RIDGE RUN Sat. September 14, 2019 We invite you to join us for this year’s CWU Invitaonal at Apple Ridge Run! Thanks to a generous donaon of land, funds, and me by Strand Fruit of Cowiche, WA, the creaon of a top‐notch running/racing venue in Central Washington has been realized. Our courses are essenally the same as previous years, and a map will be provided closer to the meet date. Location: Apple Ridge Run Cross Country Facility – 5000 Naches Heights Road, Yakima, WA Direcons: From Ellensburg or Tri‐Cies, take I‐82 to Yakima, and then change to Hwy 12 toward Naches. Aer passing the 40th Ave. exit, take the next le (Ackley Rd.). At the end of Ackley (a very short road), take a le onto Powerhouse Rd., followed by an immediate right onto Naches Heights Road. Aer several miles, Naches Heights Rd. is split by a stop sign. Take a le at the sign, and then the very next right to connue on Naches Heights. Aer a bit over a mile the road will curve le and you will come to the Naches Fire Staon. Take a le into the fire staon lot and proceed slowly down the dirt road between the orchards. Parking is alongside the course at the boom of the hill. Buses can return to the fire staon lot to park aer dropping teams off if there is not room next to the course.