ECFG-Cameroon-2020R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2011 EPIGRAPH

République du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon Paix-travail-patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Ministry of Employment and Formation Professionnelle Vocational Training INSTITUT DE TRADUCTION INSTITUTE OF TRANSLATION ET D’INTERPRETATION AND INTERPRETATION (ISTI) AN APPRAISAL OF THE ENGLISH VERSION OF « FEMMES D’IMPACT : LES 50 DES CINQUANTENAIRES » : A LEXICO-SEMANTIC ANALYSIS A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of a Vocational Certificate in Translation Studies Submitted by AYAMBA AGBOR CLEMENTINE B. A. (Hons) English and French University of Buea SUPERVISOR: Dr UBANAKO VALENTINE Lecturer University of Yaounde I November 2011 EPIGRAPH « Les écrivains produisent une littérature nationale mais les traducteurs rendent la littérature universelle. » (Jose Saramago) i DEDICATION To all my loved ones ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Immense thanks goes to my supervisor, Dr Ubanako, who took out time from his very busy schedule to read through this work, propose salient guiding points and also left his personal library open to me. I am also indebted to my lecturers and classmates at ISTI who have been warm and friendly during this two-year programme, which is one of the reasons I felt at home at the institution. I am grateful to IRONDEL for granting me the interview during which I obtained all necessary information concerning their document and for letting me have the book at a very moderate price. Some mistakes in this work may not have been corrected without the help of Mr. Ngeh Deris whose proofreading aided the researcher in rectifying some errors. I also thank my parents, Mr. -

A Cameroonian Functional Food That Could Curb the Spread of the COVID-19 Via Feces

Functional Foods in Health and Disease 2020; 10(8):324-329 www.FFHDJ.com Page 324 of 329 Research Article Open Access The acceptability of ‘Star Yellow,’ a Cameroonian functional food that could curb the spread of the COVID-19 via feces Julius Oben1*, Jude Bigoga1,2, Guy Takuissu1, Ismael Teta3 and Rose Leke2 1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Yaoundé 1, Yaounde, Cameroon; 2Biotechnology Centre, University of Yaoundé 1, Yaoundé, Cameroon; 3Helen Keller International, Rue 1771, Derrière Usine Bastos, BP 14227, Yaoundé, Cameroon *Corresponding Author: Julius Oben, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Yaoundé 1, Yaounde, Cameroon Submission Date: April 18th 2020, Acceptance Date: July 22nd, 2020, Publication Date: August 5th, 2020 Please cite this article as: Oben J, Bigoga J, Takuissu G, Teta I and Leke R. The acceptability (Star Yellow), a Cameroonian functional food that could curb the spread of the COVID-19 via feces. Functional Foods in Health and Disease 2020; (10)8: 324-329 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31989/ffhd.v10i8.715 ABSTRACT Background: COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Despite the World Health Organization’s publication of different measures to curb the spread of COVID-19, new cases are reported daily. These protective control measures put in place assumed that transmission of COVID-19 was mediated essentially through droplets released from the nasal and respiratory secretions of infected persons. Recent scientific evidence however puts forward the occurrence and shedding of active COVID-19 virus in stools of infected persons. The present study tested the acceptability of an improved version of the ‘Yellow soup’ which contains ingredients/spices with known antibacterial/antiviral properties. -

The Anglophone Cameroon Crisis: by Jon Lunn and Louisa Brooke-Holland April 2019 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8331, 17 April 2019 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: By Jon Lunn and Louisa April 2019 update Brooke-Holland Contents: 1. Overview 2. History and its legacies 3. 2015-17: main developments 4. 2018: main developments 5. Events during 2019 and future prospects 6. Response of Western governments and the UN www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: April 2019 update Contents Summary 3 1. History and its legacies 5 2. 2015-17: main developments 8 3. 2018: main developments 10 4. Events during 2019 and future prospects 12 5. Response of Western governments and the UN 13 Cover page image copyright: Image 5584098178_709d889580_o – Welcome signs to Santa, gateway to the anglophone Northwest Region, Cameroon, March 2011 by Joel Abroad – Flickr.com page. Licensed by Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 17 April 2019 Summary Relations between the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon and the country’s dominant Francophone elite have long been fraught. Over the past three years, tensions have escalated seriously and since October 2017 violent conflict has erupted between armed separatist groups and the security forces, with both sides being accused of committing human rights abuses. The tensions originate in a complex and contested decolonisation process in the late-1950s and early-1960s, in which Britain, as one of the colonial powers, was heavily involved. Federal arrangements were scrapped in 1972 by a Francophone- dominated central government. Many English-speaking Cameroonians have long complained that they are politically, economically and linguistically marginalised. -

Directory of Agricultural R&D Agencies in 31 African Countries

sustainable solutions for ending hunger and poverty Supported by the CGIAR ASTI Directory of Agricultural R&D Agencies in 31 African Countries April 2011 ABOUT ASTI The Agricultural Science and Technology Indicators (ASTI) initiative compiles, processes, and disseminates data on institutional developments and investments in worldwide agricultural R&D, and analyzes and reports on these trends. Tracking these developments in ways that facilitate meaningful comparisons among different countries, types of agencies, and points in time is critical for keeping policymakers abreast of science policy issues pertaining to agriculture. The main objective of the ASTI initiative is to assist policymakers and donors in making better informed decisions about the funding and operation of public and private agricultural science and technology agencies by making available internationally comparable information on agricultural research investments and institutional changes. Better-informed decisions will improve the efficiency and impact of agricultural R&D systems and ultimately enhance productivity growth of the agriculture sector. The ASTI initiative is managed by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and involves collaborative alliances with many national and regional R&D agencies, as well as international institutions. The initiative, which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation with additional support from IFPRI, is widely recognized as the most authoritative source of information on the support for and structure of agricultural R&D worldwide. ASTI data and associated reports are made freely available for research policy formulation and priority-setting purposes (http://www.asti.cgiar.org). ABOUT IFPRI The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI®) was established in 1975 to identify and analyze alternative national and international strategies and policies for meeting food needs of the developing world on a sustainable basis, with particular emphasis on low-income countries and on the poorer groups in those countries. -

Full Spectrum Capabilities

Full Spectrum Capabilities ISR Operations Manned ISR Operations Operate and maintain multi-mission manned airborne ISR platforms with complex mission systems Unmanned ISR Operations Operate, maintain and evaluate all sizes of Unmanned Aircraft Systems C2 Systems & Operations Operate, maintain, manage and evaluate Command & Control and ISR network systems Data Dissemination/GIS Provide video, network, geospatial and software engineering solutions, simulation and assessments Integration & CLS Execute, inspect, and certify the installation of surveillance systems on wide range of special operations vehicles 12730 Fair Lakes Circle, Suite 600 Fairfax, VA 22033 Manned ISR Training NSRW Unmanned Trainng +1 (703) 376-8993 Provide training for fixed-wing and Unmanned Aircraft Systems ISR operations, as well as Non-Standard Rotary Wing (NSRW) flight and maintenance training Specialty Aviation serve. win. perform. Rotary Wing Fixed Wing Provides full spectrum rotary and fixed wing transport flight services for passengers www.magaero.com and cargo worldwide MAKING THE WORL MAKING United Kingdom UK MOD Kosovo MENA (18 locations) Afghanistan IGO USG / DCS & FMS USG Canada Canadian OMNR Pakistan our global footprint Taiwan Jordan Jordanian Armed Forces USA (27 locations) Philippines USG Philippines Armed Forces Mauritania Mauritania Armed Forces Indonesia North Carolina Nigeria South Sudan USG Nigeria Armed Forces United Nations Malaysia Chad Royal Malaysia Police D Caribbean Chad Armed Forces Somalia US Dept. of State USG / FEMA / Fluor Cameroon Seychelles Integration Cameroon Armed Forces Seychelles Defense Force Central America, Democratic Republic Solomon Islands South America of the Congo IGO USG United Nations SMALLER AND New Zealand Mozambique NZ Defense Force MAG Australia Uganda Government of Kenya ISR Operations Uganda Armed Forces Mozambique Kenya Armed Forces Rotary W ing 12,298 UAS 47,274 118,738 flight hours SA Fixed Wing 59,165 FE R. -

Violations of Indigenous Children's Rights in Cameroon

Convention on the Rights of the Child Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Children’s Rights in Cameroon Prepared for 75th Session, Geneva, 15 May - 02 June 2017 Submitted by Cultural Survival Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org Convention on the Rights of the Child Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Children’s Rights in Cameroon I. Reporting Organization Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. II. Background Information “These peoples [the “Pygmies” and pastoralist peoples] still suffer discrimination experienced through the dispossession of their land and destruction of their livelihoods, cultures and identities, extreme poverty, lack of access to and participation in political decision-making and lack of access to education and health facilities.”1 Cameroon is home to one of the most diverse environments in Africa, with regions that have an equatorial monsoon climate, regions with a tropical humid climate, and regions with a tropical arid climate. Cameroon became an independent, sovereign nation in 1960 and a united one (when East and West Cameroon were united) in 1961.2 Cameroon has a population of over 22 million people. -

The Sheng Identity, Cultural Background and Their Influence on Communication in Academic Endevours: the Case of Machakos University College

International Journal of Social Science and Economics Invention(IJESSI) Volume 02 Issue 05 July 2016, page no. 6 to 12 Available Online at - www.isij.in Peer Review Article e-ISSN 2455 -6289 Open Access The Sheng Identity, Cultural Background and Their Influence on Communication in Academic Endevours: The Case of Machakos University College *1Mmbwanga Florence Wanguba, 2Simiyu Evelyn Etakwa Machakos University, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Linguistics and Languages, Machakos, Kenya Abstract: Young people in Kenya want to be identified with Sheng and some, in addition, want to be identified with their cultures. Sheng is a slang language originating in Nairobi, Kenya, spoken by the youth all over the country. It is a mixture of several languages, mainly English, Kiswahili and Kenyan languages. It is coined in the eastern part of the city. Youths from other parts of the country also come up with their own vocabulary which may be at variance with this Sheng. At Machakos University College there are various types of Sheng used which become a hindrance in the communication process between the students themselves and in academic discourse. Cultural background, which is manifested in incorrect pronunciations, coupled with dissimilar interpretations of the varieties of sheng also affects communication in academic discourse. The objectives of this study are designed to answer the question of whether the use of Sheng and the cultural background of the students have an impact on communication between the lecturer and the students and among students themselves. Purposive sampling will be used to get the respondents. Qualitative methods will be used to analyze the data. -

(2019) Suitability of Different Processing Techniques And

Volume 4 No : 4 (2019) Suitability of Different Processing Techniques and Sales Options for Irish Potato (Solanum Tuberusum) Cultivars in Cameroon Woin Noe, Tata Ngome Precillia, Nain Caroline Waingeh, Adjoudji Ousman, Nossi Eric Joel, Simo Brice, Yingchia Yvette, Nsongang Andre, Adama Farida, Mveme Mireille, Dickmi V. Claudette, Okolle Justine January 2019 Citation Woin N., Tata Ngome P., Waingeh N. C., Adjoudji O., Nossi E. J., Simo B., Yingchia Y., Nsongang A., Adama F., Mveme M., Dickmi V. C., Okolle J. (2019). Suitability of Different Processing Techniques and Sales Options for Irish Potato (Solanum Tuberusum) Cultivars in Cameroon. FARA Research Report. Volume 4(4): PP 83. Corresponding Author Dr.Tata Ngome ( [email protected] ) FARA encourages fair use of this material. Proper citation is requested Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) 12 Anmeda Street, Roman Ridge PMB CT 173, Accra, Ghana Tel: +233 302 772823 / 302 779421 Fax: +233 302 773676 Email: [email protected] Website: www.faraafrica.org Editorials Dr. Fatunbi A.O ([email protected]); Dr. Abdulrazak Ibrahim ([email protected] ), Dr. Augustin Kouevi([email protected] ) and Mr. Benjamin Abugri([email protected]) ISSN: 2550-3359 About FARA The Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) is the apex continental organisation responsable for coordination and advocating for agricultural research-for-development. (AR4D). It serves as the entry point for agricultural research initiatives designed to have a continental reach or a sub-continental reach spanning more than one sub-region. FARA serves as the technical arm of the African Union Commission (AUC) on matters concerning agricultural science, technology and innovation. -

AFR 17/16/97 Cameroon

CAMEROON Blatant disregard for human rights Amnesty International, 16 September 1997 AI Index: AFR 17/16/97 2 Cameroon: Blatant disregard for human rights Table of Contents Introduction 1 Political developments in Cameroon 2 Cameroon's obligations under international human rights law 4 Arrests and detention of critics and opponents of the government 5 Legal restrictions on the right to freedom of expression 5 Arbitrary detention 6 Political opponents 7 Social Democratic Front (SDF) 7 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 12 Union nationale pour la démocratie et le progrès (UNDP) 13 Other political opponents 15 Journalists 16 Detention and imprisonment 16 Harassment and physical assault 20 Human rights activists 21 Students at the University of Yaoundé 22 Illegal detention and ill-treatment by traditional rulers 24 Torture and ill-treatment 27 Students at the University of Yaoundé 28 Detainees arrested in North-West Province in March and April 1997 29 Torture and ill-treatment in Cameroon’s prisons 31 Harsh prison conditions 33 AI Index: AFR 17/16/97 Amnesty International, 16 September 1997 Cameroon: Blatant disregard for human rights 3 Use of excessive and lethal force by the security forces 34 The death penalty 37 Cameroon and the international community 38 Amnesty International, 16 September 1997 AI Index: AFR 17/16/97 4 Cameroon: Blatant disregard for human rights Introduction Fundamental human rights are persistently violated in Cameroon. In many cases these violations occur when the law is deliberately ignored or contravened by the authorities. There is little accountability for human rights violations and the perpetrators generally act with impunity. -

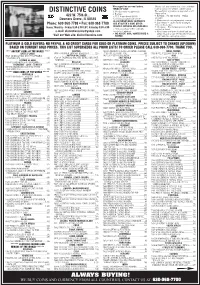

Distinctive Coins |

We suggest fax or e-mail orders. Please call and reserve the coins, and then TERMS OF SALE mail or fax us the written confirmation. DISTINCTIVE COINS 1. No discounts or approvals. We need your signature of approval on all 2. Postage: charge sales. 422 W. 75th St., a. U.S. insured mail $5.00. 4. Returns – for any reason – within b. Overseas registered $20.00. 21 days. Downers Grove, IL 60516 5. Minors need written parental consent. ALL INTERNATIONAL SHIPMENTS 6. Lay Aways – can be easily arranged. Phone: 630-968-7700 • Fax: 630-968-7780 ARE AT BUYER’S RISK! OTHER Give us the terms. Hours: Monday - Friday 9:30-5:00 CST; Saturday 9:30-3:00 INSURED SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE. 7. Overseas – Pro Forma invoice will be c. Others such as U.P.S. or FedEx mailed or faxed. e-mail: [email protected] need street address. 8. Most items are one-of-a-kind and are 3. WE ACCEPT VISA, MASTERCARD & subject to prior sale. Distinctive Coins is Visit our Web site: distinctivecoins.com PAYPAL! not liable for cataloging errors. PLATINUM & GOLD BUYERS: NO PAYPAL & NO CREDIT CARDS FOR GOLD OR PLATINUM COINS. PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE (UP/DOWN) BASED ON CURRENT GOLD PRICES. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR LISTS! TO ORDER PLEASE CALL 630-968-7700. THANK YOU. **** ANCIENT COINS OF THE WORLD **** AUSTRIA 1891A 5 FRANCOS K-12 NGC-AU DETAILS CLEANED INDIA, MEWAR GREECE-CHIOS 1908 5 CORONA K-2809 NGC-MS63 60TH .............225 1 YR TYPE PLEASANT TONE .................................380 1928 RUPEE Y-22.2 NGC-MS64 THICK ...................110 (1421-36) DUCAT NGC-MS61 -

The Use of Camfranglais in the Italian Migration Context

Paper The use of Camfranglais in the Italian migration context by Sabrina Machetti & Raymond Siebetcheu (University of Foreigners of Siena, Italy) [email protected] [email protected] May 2013 SABRINA MACHETTI, RAYMOND SIEBETCHEU University of Foreigners of Siena (Italy) The use of Camfranglais in the Italian migration context 1. INTRODUCTION It is nearly ten years since the concept of lingue immigrate (Bagna et al., 2003), was formulated. To date, immigrant minority languages are poorly investigated in Italy. Actually, when referring to applied linguistics in the Italian context, research tends to focus on Italian language learning and acquisition by immigrants but it does not take into consideration contact situations between Italian and Immigrant languages. The linguistic mapping of these languages (Bagna, Barni, Siebetcheu, 2004; Bagna, Barni, 2005; Bagna; Barni, Vedovelli, 2007) so far undertaken empowers us to consider them as belonging to a linguistic superdiversity in Italy (Barni, Vedovelli 2009). Consequently, rather than being an impediment, immigrant languages shall enrich research in this area of study, without disregarding the complexity at both individual and collective levels. Bagna, Machetti and Vedovelli (2003) distinguish Immigrant languages from Migrant languages. For these authors, unlike Migrant languages which are languages passing through, Immigrant languages are used by immigrant groups that are able to leave their mark on the linguistic contact in the host community. A clear example of such immigrant language is called Camfranglais, an urban variety that stems from a mixture of French, English, Pidgin English and Cameroonian local languages (Ntsobé et al., 2008). On the basis of this backdrop, we present a case study started in 2008 across various Italian cities that focuses on the outcome of the interaction between Italian and Camfranglais. -

Introduction

Introduction There are few art forms as intrinsically political as palace architecture. As both residence as well as the structure within which political decision-making occurs, the palace commonly constitutes the public identity of a ruler. Palaces in northern Cameroon also provide venues for judicial proceedings and con- tain prison cells, amongst other potential functions. In addition to the ruler himself, the palace is generally inhabited by his wives and concubines, their female servants, and a number of male guards. The vast majority of these resi- dents usually derive from local, indigenous populations, while the ruler is of the ruling Fulɓe ethnicity.1 It is through the lens of ethnicity that the archi- tecture of this region has largely been viewed. In contrast, by focusing on the late nineteenth-century palace of Ngaoundéré, capital of Adamaoua Region, and with subsidiary research conducted at fourteen other palaces constructed since the early nineteenth century in Adamaoua and North Regions, this study considers the palace architecture of northern Cameroon as central to the for- mation of political authority in ways that cross ethnic boundaries. The majority of the research area for this study may be divided into a series of political entities, commonly referred to as lamidats, with Fulɓe leaders at the helm. The specific communities ruled by these leaders, or laamiiɓe (pl., sing. laamiiɗo) are composed of a politically dominant Fulɓe population, but who are a numeric minority amongst a number of other local identities, in- cluding most notably the Mboum, Dìì, Gbaya, Vouté, Namchi, Fali, Péré, and Bata. The suzerainty of the Fulɓe was established in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries after they arrived in the region from what are now northeastern Nigeria and southern Tchad.