Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before We Reach the End

ABSTRACT BEFORE WE REACH THE END This novel follows young tenacious Sybil as she navigates her traumatic past, and tumultuous present. Beginning in 1989 Tucson, AZ, Sybil contemplates her identity as a daughter through the lens of a motherless child. The story transitions to her present adolescence where she challenges her expectations of herself, as well as her role as a sister, friend, and daughter. Through her humorous voice which counteracts the overwhelming grief she experiences, we learn about love and loss, friendships and relationships, and the blurring of in-between moments where every end is a beginning, and every beginning, an end. Samantha Kim Rogers May 2017 BEFORE WE REACH THE END by Samantha Kim Rogers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2017 APPROVED For the Department of English: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Samantha Kim Rogers Thesis Author Steven Church (Chair) English Corrinne Hales English John Beynon English For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

* * * * Fat Wreck Chords

fanzine * webzine * Fat Wreck Chords * The Causey Way * The Gossip * Selby Tigers * Smogtown * Youth Brigade From the editors: You're probably wondering who the hell we are, right? Basically, a bunch of us used to write for a punk magazine called B-sides or something like that. Maybe Flipside? It was actually the longest continuously publishing punk rock magazine in America. It may still be. I can't say for sure. All I know PO Box 42124 from my personal experience is that I did an interview with Against All Authority sometime during the summer of 1999, and that interview is set to Los Angeles, CA 90042 run in the next issue. So if it does still come out, at least we know it's timely. www.razorcake.com Anyway, if you want to know more about Flipside and its possible demise, check out Todd's column. And now on to the things I do know about. I know Todd left Flipside and wanted to start a new magazine, so first he Email went to Tucson to meet with Skinny Dan and Katy. Together, the three of Sean <[email protected]> them came up with the name and the beginnings of a web zine. Shortly after Todd<[email protected]> that, Todd took a vacation to Florida to hang out with me and drink away his Rich Mackin <[email protected]> woes. While he was there, we started talking about the web zine and I said Nardwuar <[email protected]> something like, "What about poor fuckers like me who can only use the inter- Designated Dale<[email protected]> net in half hour intervals at the library?" Todd said something like, "You're Everyone else can be reached c/o Razorcake. -

Dustin Lynch Loretta Lynn

Dustin Lynch Singer/songwriter born 5/14/1985 in Tullahoma, TN. 2 40 1 Cowboys and Angels 02/15/12 10/03/12 bbr 18 22 2 She Cranks My Tractor 11/28/12 03/13/13 bbr 23 33 3 Wild In Your Smile 08/14/13 01/08/14 bbr 1(1) 27 4 Where It's At 04/09/14 09/17/14 bbr 1(1) 40 5 Hell Of A Night 12/17/14 09/02/15 bbr 1(1) 34 6 Mind Reader 10/21/15 05/18/16 bbr 1(1) 32 7 Seein' Red 07/27/16 02/08/17 bbr 1(3) 28 8 Small Town Boy 03/29/17 09/06/17 bbr 37 19 9 I'd Be Jealous Too 11/15/17 04/07/18 bbr 1(1) 30 10 Good Girl 05/12/18 01/12/19 bbr 1(2) 39 11 Ridin' Roads 04/27/19 12/28/19 bbr 13 38^ 12 Momma's House 04/11/20 12/26/20 bbr Loretta Lynn Singer/songwriter born Loretta Webb 4/14/1932 in Butcher Hollow, KY. Sister of Crystal Gayle and songwriter Peggy Sue Wright. 4 8 1 Hey Loretta 12/07/73 01/18/74 mca 6 9 2 They Don't Make 'Em Like My Daddy 05/31/74 06/14/74 mca 1(2) 11 3 As Soon As I Hang Up The Phone Conway Twitty 06/21/74 07/19/74 mca 1(1) 11 4 Trouble In Paradise 10/04/74 11/08/74 mca 7 10 5 Pill, The 02/21/75 03/07/75 mca 1(1) 14 6 Feelins' Conway Twitty 06/27/75 08/22/75 mca 8 10 7 Home 08/15/75 09/12/75 mca 2 11 8 When The Tingle Becomes A Chill 11/28/75 01/09/76 mca 19 7 9 Red White And Blue 04/30/76 05/21/76 mca 4 9 10 Letter, The Conway Twitty* 06/25/76 07/16/76 mca 1(1) 12 11 Somebody Somewhere 10/01/76 11/12/76 mca 1(2) 11 12 She's Got You 03/11/77 04/15/77 mca 2 12 13 I Can't Love You Enough Conway Twitty 06/10/77 07/22/77 mca 9 10 14 Why Can't He Be You 08/19/77 09/23/77 mca 1(1) 15 15 Out Of My Head And Into My Bed 12/09/77 01/27/78 -

Sept 2012 #176.Indd

NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 Project1_Layout 1 8/30/12 12:32 PM Page 1 CD, DVD, & Tape Duplication, Replication, Printing, Packaging, Graphic Design, and Audio/Video Conversions we make it easy! Great prices Terrific turnaround time Hassle - free, first - class personal service Jewel case package prices just got even better! 500 CD Package starts at $525 5-6 business days turnaround 300 CD Package starts at $360 4-5 business days turnaround 100 CD Package starts at $170 3-4 business days turnaround. Or check out our duplication deals on custom printed sleeve, digipaks, wallets, and other CD/DVD packages Call or email today to get your project moving! 615.244.4236 [email protected] or visit wemaketapes.com for a custom quote On Nashville’s Historic Music Row For 33 Years 118 16th Avenue South - Suite 1 Nashville, TN 37203 (Located just behind Off-Broadway Shoes) Toll Free: 888.868.8852 Fax: 615.256.4423 Become our fan on and follow us on to receive special offers! NashvilleMusicGuide.com 2 NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 Taking Bluegrass to New Contents Audiences 31 Tommy Womack Letter from the Editor Editor & CEO Randy Matthews [email protected] Settling in to Americana Americana was our special is- ber issue of Nashville Music Guide for our Nashville Past & sue for the month of Septem- Present Issue. We will have stories from numerous contributors Managing Editor Amanda Andrews 34 Dallas Moore ber. We would like to thank and supporters of The Guide that have seen it transition over the [email protected] Independent & Loving It Jed Hilly of AMA for helping past eighteen years, along with numerous other stories about Dove Awards us with this issue and all of the Nashville past & present in the music industry. -

Listening for a Life

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2004 Listening for a Life Patricia Sawin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Sawin, P. (2004). Listening for a life: A dialogic ethnography of Bessie Eldreth through her songs and stories. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Listening for a Life 5/27/04 2:23 PM Page i Listening for a Life A Dialogic Ethnography of Bessie Eldreth through Her Songs and Stories Listening for a Life 5/27/04 2:23 PM Page ii Listening for a Life 5/27/04 2:23 PM Page iii Listening for a Life A Dialogic Ethnography of Bessie Eldreth through Her Songs and Stories Patricia Sawin Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Listening for a Life 5/27/04 2:23 PM Page iv Copyright © 2004 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the University Researcch Council at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sawin, Patricia. Listening for a life : a dialogic ethnography of Bessie Eldreth through her songs and stories / Patricia Sawin. -

2015 STREET DATES SEPTEMBER 25 OCTOBER 2 Orders Due August 28 Orders Due September 4 9/22/15 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

ISSUE 20 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com NEW RELEASE GUIDE 2015 STREET DATES SEPTEMBER 25 OCTOBER 2 Orders Due August 28 Orders Due September 4 9/22/15 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Beginner's Bible The Beginner's Bible (4DVD) TL DV 610583512397 31190-X $39.95 8/21/15 Beginner's Bible The Beginner's Bible: Volume 4 (DVD) TL DV 610583501995 30964-X $9.95 8/21/15 CPO Sharkey: The Complete 2nd CPO Sharkey TL DV 610583503593 31062-X $29.95 8/21/15 Season (3DVD) Harris, Emmylou Profile: Best Of Emmylou Harris (Vinyl) RRW A 081227952402 3258 $21.98 8/21/15 Last Update: 08/10/15 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Beginner's Bible TITLE: The Beginner's Bible (4DVD Box Set) Label: TL/Time Life/WEA Config & Selection #: DV 31190 X Street Date: 09/22/15 Order Due Date: 08/21/15 UPC: 610583512397 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 4 SRP: $39.95 Alphabetize Under: B ALBUM FACTS Genre: Children Packaging Specs: 4-DVD Box Set (4 regular amarays in a slip case); Dimensions: 7.5" x 5.5" x 2.5"; Running Time: 390 minutes Description: NOW GET THE COMPLETE BOX SET! FOUR VOLUMES OF THE BEGINNER’S BIBLE… TIMELESS STORIES OF FAITH, FORGIVENESS, COURAGE, COMPASSION & MORE! THE BEGINNER’S BIBLE is an animated children’s video series of timeless bible stories for preschoolers, based on the best-selling children’s book by the same name. -

P104-121 Discography Section 4

P104-121_Discography4-NOV14_Lr1_qxd_P104-121 12/9/14 4:26 PM Page 104 {}MIKE CURB : 50 Years DISCOGRAPHY “NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE” ARTIST: GLORIA GAYNOR WRITER: CLIFTON DAVIS PUBLISHER: JOBETE “BACK IN THE COUNTRY” ARTIST: ROY ACUFF WRITER: EDWARD FUTCH PUBLISHER: SONY/ATV MILENE 1M2USIC1 CO, INC. TIME: 2:56 PRODUCER: MECO MONARDO, TONY BONGIOVI AND JAY ELLIS SPECIAL THANKS: STAN 1M2USIC5 (ASCAP) TIME: 2:14 MORESS MGM 2006 463, 1974 Roy Acuff was born in 1903 in Maynardsville, had the privilege of working with him in the 1970s, Gloria Gaynor’s version of “Never Can Say Goodbye” The song was originally recorded by the Jackson 5; Tennessee, and was known as the King of Country including his Billboard Country chart recording of “Back was a multi-genre hit; number one (for five weeks) on the Gaynor’s version came out as disco was becoming Music. Acuff is a member of the Country Music Hall of In The Country.” Dance Sales chart, number one (for four weeks) on the accepted by major labels. “This record was the first Fame and won a Lifetime Achievement Grammy. Curb Club chart in Billboard ; number 11 on the Adult number one hit on Billboard ’s Dance chart and the first Contemporary, number nine on the Hot 100, and it major dance hit,” said Mike Curb. “Gloria actually made the Billboard R&B charts in the fall and winter of became the first Disco Diva before Donna Summer took 1974-1975. that title one year later.” “TOO FAR, TOO LONG” ARTIST: DEGARMO AND KEY WRITER: EDDIE DEGARMO, DANA KEY PUBLISHER: “THINGS” ARTIST: RONNIE DOVE WRITER: BOBBY DARIN PUBLISHER: HUDSON BAY MUSIC (BMI) TIME: 2:31 1©2 19882 , 1989 DKB MUSIC (ADMIN. -

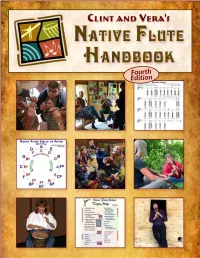

Clint & Vera's Native Flute Handbook

Clint & Vera’s Native Flute Handbook 1 2 July 22, 2016 Clint & Vera’s Native Flute Handbook Fourth Edition Course materials for participants of Native Flute Schools, Retreats, Workshops, and Gatherings facilitated by Clint and Vera by Clint Goss and Vera Shanov July 22, 2016 Private electronic distribution Not for sale or distribution Copyright ©2016 by Clint Goss, All Rights Reserved. For information, contact Clint Goss at . Clint & Vera’s Native Flute Handbook 3 For our current workshop schedule: To sign up for our monthly newsletter: http://www.ClintGoss.com/calendar.html http://www.ClintGoss.com/newsletter.html 4 July 22, 2016 Clint & Vera’s Native Flute Handbook 5 Table of Contents Rhythmic Chirping ..................... 45 You can click on any of the page numbers to FluteCasts .................................. 47 take you directly to that chapter. Technology and Headphones ........ 49 Random Melodies ...................... 51 Preface ......................................... 9 The Heavenly Rut ...................... 55 Right in Tune, Revisited .............. 59 Part 1 – Flute Playing Back to Back .............................. 65 One-Breath Solos ........................ 15 Active Listening .......................... 67 Long Tones ................................. 17 Playing (from the Heart) Over Changes ............................. 71 The Scale Song ........................... 19 Alternate Scales .......................... 75 Right in Tune .............................. 23 A Scale Codex ............................ 89 No Pain, -

311 Thm-R0311 Love Song 311 Thmr0406 I Still Love Y

#1 Nelly PS1560-09 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 THM-R0402 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 THM-R0311 LOVE SONG 311 THMR0406 I STILL LOVE YOU 702 THM-H0307 Where My Girls At 702 Sound Choice ALMOST HOME Morgan, Craig THM-C0307 Voices Carry ´til Tuesday Sound Choice Through The Iris 10 Years THM-T0606 Wasteland 10 Years THM-T0512 Dreadlock Holiday 10cc ZGY78-10 I´m Not In Love 10cc ZGY75-06 FAR AWAY 12 Stones THM-R0411 1,2,3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. SC8191-11 Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down THM-T0608 Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down THM-T0507 Duck and Run 3 Doors Down CBE4-11-11 Here Without You 3 Doors Down FH3208-03 HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 Doors Down THM-R0310 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Sound Choice Kryptonite 3 Doors Down THM-T0512 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down FH3208-01 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down FH7302-01 Landing In London 3 Doors Down THM-T0603 Let Me Go 3 Doors Down THM-T0503 Live For Today 3 Doors Down THM-T0511 THE ROAD I´M ON 3 Doors Down THM-R0306 When I´m Gone 3 Doors Down Sound Choice When I´m Gone 3 Doors Down FH3208-02 The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars THM-T0606 What´s Up 4 Non Blondes Sound Choice We´re In The Money 42nd St. SC8127-10 We´re In The Money 42nd Street KA LEB1010-01 SURRENDER 4Him THM-S0304 Candy Shop 50 Cent THM-T0505 Disco Inferno 50 Cent THM-T0504 IN DA CLUB 50 Cent THM-H0305 Just a Lil Bit 50 Cent THM-T0508 Outta Control 50 Cent THM-T0511 P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Artist

Chansons en anglais - Songs in English ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE 10 Years Through The Iris 21 Demands Give Me A Minute Wasteland 2Unlimited No Limit 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun More Than This Be Like That These Are The Days Duck And Run Trouble Me Every Time You Go 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody'S Been Sleepin Here By Me 101 Dalmations Cruella De Vil Here Without You 10Cc Donna It'S Not My Time Dreadlock Holiday Krypnotite I'M Not In Love Landing In London Rubber Bullets Let Me Be Myself The Things We Do For Let Me Go Love Live For Today The Wall Street Shuffle Loser 112 Come See Me Road I'M On Dance With Me The Road I'M On It'S Over Now Train Only You When I'M Gone Peaches And Cream 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 12 Stones We Are One Love Is Enough 1910 Fruit Gum Co. 1,2,3 Red Light 30 Seconds To Mars The Bury Me Kill Simon Says The Kill 2 Live Crew Doo Wah Diddy 30H!3 & Katy Perry Starstrukk Me So Horny 30H!3 And Katy Perry Starstrukk We Want Some Pussy 311 All Mixed Up 2 Pac Changes Down Thugz Mansion I'Ll Be Here Awhile Until The End Of Time You Wouldn'T Believe 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 38 Special Caught Up In You 2 Pistols And Ray J You Know Me Hold On Loosely 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If I'D Been The One Page 1 of/de 329 Chansons en anglais - Songs in English ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night 50 Cent And Ayo Technology Timberlake Second Chance 50 Cent Feat.Ne-Yo Baby By Me Wildeyed Southern Boys, -

Miscellaneous Songs (Country Music Lyrics, Volume 8)

MISCELLANEOUS SONGS (COUNTRY MUSIC LYRICS, VOLUME 8) 23 OCTOBER 2008 UPDATED 27 NOVEMBER 2020 ALL IN KEY OF A, UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED © 2008-2020 Joseph George Caldwell. All rights reserved. Posted at Internet website http://www.foundationwebsite.org. May be copied or reposted for non-commercial use, with attribution to author and website. FOREWORD This is an eighth volume of lyrics to popular songs, to assist learning to play the guitar by ear, as described in the article, How to Play the Guitar by Ear (for Mathematicians and Physicists), posted at Internet website http://www.foundationwebsite.org. As discussed in the foreword to Volume 1, the purpose of assembling these lyrics is to provide the student with a large number of songs from which he may choose ones for which he knows the melody and enjoys singing. Since everyone’s taste is different, and the student may not be familiar with the songs that I know (many from decades ago), it is the intention to provide a large number of popular songs from which the student may choose. I believe that learning the guitar is facilitated by practicing a number of different songs in a practice session, and playing each one only a couple of times, perhaps in a couple of different keys. In order to do this, it is important to have a large collection of lyrics available. This volume is a miscellaneous collection of songs, mainly older popular songs from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. As in Volume 1, I have deliberately omitted noting the chords to be played on each song, if it is my opinion that the beginning student should be able to figure them out easily – e.g., chords are omitted for most two-chord or three-chord songs.