The Score (London, 1949-1961)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Tocc0298notes.Pdf

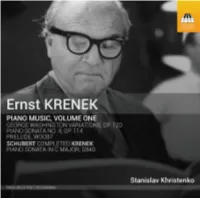

ERNST KRENEK AT THE PIANO: AN INTRODUCTION by Peter Tregear Ernst Krenek was born on 23 August 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and grew up in a house that overlooked the original gravesites of Beethoven and Schubert. His parents hailed from Čáslav, in what was then Bohemia, but had moved to the city when his father, an officer in the commissary corps of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army, had received a posting there. Vienna, the self-styled ‘City of Music’, considered itself to be the well-spring of a musical tradition synonymous with the core values of western classical music, and so it was no matter that neither of Krenek’s parents was a practising musician of any stature: Ernst was exposed to music – and lots of it – from a very young age. Later in life he recalled with wonder the fact that ‘walking along the paths that Beethoven had walked, or shopping in the house in which Mozart had written “Don Giovanni”, or going to a movie across the street from where Schubert was born, belonged to the routine experiences of my childhood’.1 As befitting an officer’s son, Krenek received formal musical instruction from a young age, in particular piano lessons and instruction in music theory. The existence of a well-stocked music hire library in the city enabled him to become, by his mid-teens, acquainted with the entire standard Classical and Romantic piano literature of the day. His formal schooling coincidentally introduced Krenek to the literature of classical antiquity and helped ensure that his appreciation of this music would be closely associated in his own mind with his appreciation of western history and classical culture more generally. -

Hercules: Celebrity Strongman Or Kindly Deliverer?

Hercules: Celebrity Strongman or Kindly Deliverer? BY J. LARAE FERGUSON When Christoph Willibald Gluck’s French Alceste premiered in Paris on 23 April 1776, the work met with mixed responses. Although the French audience loved the first and second acts for their masterful staging and thrilling presentation, to them the third act seemed unappealing, a mere tedious extension of what had come before it. Consequently, Gluck and his French librettist Lebland Du Roullet returned to the drawing board. Within a mere two weeks, however, their alterations were complete. The introduction of the character Hercules, a move which Gluck had previously contemplated but never actualized, transformed the denouement and eventually brought the opera to its final popular acclaim. Despite Gluck’s sagacious wager that adding the character of Hercules would give to his opera the variety demanded by his French audience, many of his followers then and now admit that something about the character does not fit, something of the essential nature of the drama is lost by Hercules’ abrupt insertion. Further, although many of Gluck’s supporters maintain that his encouragement of Du Roullet to reinstate Hercules points to his acknowledged desire to adhere to the original Greek tragedy from which his opera takes its inspiration1, a close examination of the relationship between Gluck’s Hercules and Euripides’ Heracles brings to light marked differences in the actions, the purpose, and the characterization of the two heroes. 1 Patricia Howard, for instance, writes that “the difference between Du Roullet’s libretto and Calzabigi’s suggests that Gluck might have been genuinely dissatisfied at the butchery Calzabigi effected on Euripides, and his second version was an attempt not so much at a more French drama as at a more classically Greek one.” Patricia Howard, “Gluck’s Two Alcestes: A Comparison,” Musical Times 115 (1974): 642. -

Programmheft 13.11.2015

Wider das Vergessen Freitag, 13. November 2015, 20 Uhr Spätgotische Stadtkirche Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 418. Konzert der MUSIK AM 13. 2 Am Ausgang erbitten wir Ihre Spende (empfohlener Betrag 10,- ¤). Herzlichen Dank dafür! Die MUSIK AM 13. wird wohlwollend unterstützt durch die Stadt- und Luthergemeinde, die Gesamtkirchengemeinde Bad Cannstatt, den Evangelischen Oberkirchenrat, die Jörg-Wolff-Stiftung, die Martin Schmälzle-Stiftung, die Stadt Stuttgart und das Land Baden-Württemberg. Allen Förderern gilt unser herzlicher Dank. 3 Programm Wider das Vergessen Anton Bruckner 1824-1896 Locus iste WAB 23 Os justi WAB 30 Christus factus est WAB 11 Motetten für vierstimmigen Chor a capella Luigi Nono 1924-1990 Ricorda cosa ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz (1966) (Erinnere dich, was sie dir in Auschwitz angetan haben) für Magnettonband Anton Bruckner Libera me für fünfstimmigen Chor und Orgel WAB 22 Totenlied »O ihr, die ihr heut mit mir zum Grabe geht« WAB 47,1 Iam lucis orto sidere für vierstimmigen Männerchor WAB 18 Tantum ergo für vierstimmigen Chor und Orgel WAB 42 Choral »Dir Herr, dir will ich mich ergeben« für vierstimmigen Chor WAB 12 Karlheinz Stockhausen 1928-2007 Gesang der Jünglinge im Feuerofen (1955) für Vierkanal-Elektronik Anton Bruckner Virga jesse für vierstimmigen Chor a cappella WAB 52 Tota pulchra es für vierstimmigen Chor und Orgel WAB 46 Ave Maria für siebenstimmigen Chor a cappella WAB 6 Ioanna Solomonidou Orgel Otto Kränzler Elektronik Cantus Stuttgart Jörg-Hannes Hahn Leitung 19.15 Uhr Einführung Prof. Dr. Rudolf Frisius 4 Zum Programm Größer könnten die Gegensätze kaum sein. Auf der einen Seite die Motetten Anton Bruckners, reduziert auf die menschliche Stimme und die physische Präsenz der Sänger im Raum. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Kolloquium 6 Sprachkomposition in Der Neuen Musik Seit 1945 Was

1 --=----~-- - - -- - 1 Kolloquium 6 Sprachkomposition in der Neuen Musik seit 1945 Rudolf Stephan Was bedeutet der Verzicht auf fixierte Tonhöhen? Überlegungen zur Situation der Sprachkomposition Der Titel dieses Kolloquiums, «Sprachkomposition in der Neuen Musik seit 1945», könnte den Eindruck erwecken, als markiere das genannte Jahr eine Zäsur in der Musikgeschichte, oder doch wenigstens in der Ent- wicklung des angesprochenen Problems. Dies ist jedoch nicht der Fall. Die serielle Musik, die doch die erste wirklich neue in der Zeit nach dem Kriege war, entstand erst um (vornehmlich nach) 1950, die Vokalwerke, deren Sprachbehandlung Veranlassung gegeben hat (und noch immer gibt) sie als neuartig zu betrachten, wurden erst in den Fünfzigerjahren geschaffen. Karlheinz Stockhausen begann denn auch seine vergleichende Betrachtung dreier einschlägiger Werke, die er unter dem Titel «Sprache und Musik» (zuerst) in den Darmstädter Beiträgen zur neuen Musik (1, 1958, S. 57-81) erscheinen ließ mit einem Hinweis auf die Urauffilhrungsdaten der drei besprochenen Werke: 1955/56. Gegenstand der Betrachtung waren die Werke Le marteau sans maitre von Pierre Boulez, II canto sospeso von Luigi Nono und der eigene Gesang der Jünglinge. Diese Werke sind, ebenso wie der genannte, vielfach nachgedruckte Aufsatz Stockhausens (z.B. in: Die Reihe 6, 1960, S. 36-58, abweichend in Karlheinz Stockhausen: Texte, 2, 1964), als Dokumente einer bestimmten Phase der Musikentwicklung (und der zugehörigen Überlegungen) allbekannt. Das mit ihnen beginnende Neue wird gewiß -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Bmus 1 Analysis Week 9 Project 2

BMus 1 Analysis: Week 9 1 BMus 1 Analysis Week 9 Project 2 Just to remind you: the second project for this module is an essay (c. 1500 words) on one short post-tonal work from the list below. All of the works can be found in the library; if they’re not available for any reason, ask me for a copy. (Most can be found online as well.) Béla Bartók, 44 Duos for Violin, no. 33: ‘Erntelied’ (‘Harvest Song’) Harrison Birtwistle, Duets for Storab, any two movements Ruth Crawford-Seeger, String Quartet, movt. 2: ‘Leggiero’ or movt. 3: ‘Andante’ György Kurtag, Játékok Book 6, ‘In memoriam András Mihály’ Elisabeth Lutyens, Présages op. 53, theme and variations 1-2. Olivier Messiaen, Préludes, no. 1: ’La Colombe’ Kaija Saariaho, Sept Papillons, movements 1 and 2 Arnold Schoenberg, 6 Little Piano Pieces, Op.19: No. 2 (Langsam) Igor Stravinsky, 3 pieces for String Quartet, no. 1 Anton Webern, Variations op 27: no. 2 What to cover You may format your essay as you wish, according to what best suits the piece you’ve selected. However, you should aim to comment on the following (interrelated) features of your chosen work: • Formal Design o How is this articulated? This may involve pitch / tempo / changes of texture / dynamics / phrasing and other musical features. • Pitch Structure o Use of interval / mode(s) / pitch sets / 12-note chords and other techniques • Nature and Handling of Melodic and Harmonic Materials o How is the material constructed, treated, developed and/or elaboration in the work? Do not forget the importance of rhythm as well as pitch. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Piano Tamara Stefanovich, Piano

Thursday, March 12, 2015, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano Tamara Stefanovich, piano The Piano Music of Pierre Boulez PROGRAM Pierre Boulez (b. 1925) Notations (1945) I. Fantastique — Modéré II. Très vif III. Assez lent IV. Rythmique V. Doux et improvisé VI. Rapide VII. Hiératique VIII. Modéré jusqu'à très vif IX. Lointain — Calme X. Mécanique et très sec XI. Scintillant XII. Lent — Puissant et âpre Boulez Sonata No. 1 (1946) I. Lent — Beaucoup plus allant II. Assez large — Rapide Boulez Sonata No. 2 (1947–1948) I. Extrêmement rapide II. Lent III. Modéré, presque vif IV. Vif INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Boulez Sonata No. 3 (1955–1957; 1963) Formant 3 Constellation-Miroir Formant 2 Trope Boulez Incises (1994; 2001) Boulez Une page d’éphéméride (2005) Boulez Structures, Deuxième livre (1961) for two pianos, four hands Chapitre I Chapitre II (Pièces 1–2, Encarts 1–4, Textes 1–6) Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ – Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsor Françoise Stone. Hamburg Steinway piano provided by Steinway & Sons, San Francisco. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES THE PROGRAM AT A GLANCE the radical break with tradition that his music supposedly embodies. If Boulez belongs to an Tonight’s program includes the complete avant-garde, it is to a French avant-garde tra - piano music of Pierre Boulez, as well as a per - dition dating back two centuries to Berlioz formance of the second book of Structures for and Delacroix, and his attitudes are deeply two pianos. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry.