Introduction & Historic Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republicans Gather at Chicago

Republicans Gather at Chicago by Michael Burlingame http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/journal/2010/07/29/republicans-gather-at-chicago/ The convention opened on Wednesday, May 16, with David Wilmot of Pennsylvania serving as temporary chairman. Orville Browning called him “a dull, chuckle headed, booby looking man” who “makes a poor presiding officer.” The convention hall, specially built for the occasion, was known as the Wigwam because it resembled an Indian longhouse. A large, clumsy, solid, barn-like structure, measuring 100 x 180 feet, with a capacity of twelve thousand people, it was constructed “of rough timber, decorated so completely with flags banner, bunting, etc., that when filled it seemed a gorgeous pavilion aflame with color and all Inside the “The Wigwam” aflutter with pennants and streamers.” The interior resembled a Chicago, Illinois, 1860 huge theater whose stage was occupied by the delegates and the press. The acoustics were so good that an ordinary voice could easily be heard throughout the building. One journalist deemed it a “small edition of the New York Crystal Palace.” "Republicans Gather at Chicago " p. 2 An “overflowing heartiness and deep feeling pervaded the whole house,” John G. Nicolay remembered. “No need of a claque, no room for sham demonstration here! The galleries were as watchful and earnest as the platform. There was something genuine, elemental, uncontrollable in the moods and manifestations of the vast audience.” The city was awash with visitors, some of whom wound up sleeping on tables at -

On MONDAY, September 24, the Roundtable Welcomes MRRT Member Rufus K

VOL. LII, NO. 9 Michigan Regimental Round Table Newsletter—Page 1 September 2012 Last call to sign-up for the October 27-28 field trip to the battlefields of First and Second Bull Run. Should you have the time and inclination to join the thirty one members slated to go, contact one of the trip coordinators. You can find their contact information and all other particulars on our website at: www.farmlib.org/mrrt/annual_fieldtrip.html. On MONDAY, September 24, the Roundtable welcomes MRRT member Rufus K. Barton, III. Rufus will discuss the “Missouri Surprise of 1864, the battle of Fort Davidson”. The crucial struggle for control of Missouri has been neglected by most Civil War historians over the years. Rufus will explain that while President Lincoln said he had to have Kentucky, the Union occupation of Missouri saved his “bacon”. The Battle of Fort Davidson on September 27, 1864 was the opening engagement of Confederate Major General Sterling Price’s raid to “liberate” his home state. The battle’s outcome played a key role in the final Union victory in Missouri. Rufus grew up in the St. Louis, Missouri area and his business opportunities brought him to Michigan in 1975. Rufus was also an U.S. Army Lieutenant and a pilot for 30 years. Studying the Civil War is one of his hobbies. The MRRT would like to thank William Cottrell for his exceptional presentation, “Lincoln’s Position on Slavery—A Work In Progress”. Bill presented the MRRT a thoughtful and well researched presentation on the progression of Abraham Lincoln’s thinking on the slavery question and how it culminated in action during his Presidency. -

Schedule/Results (5-6) Fresno State Men's Basketball

2012-13 FRESNO STATE MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES FRESNO STATE MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES Men’s Basketball Contact: Stephen Trembley - Assistant Director of Communications 559-278-6178 (office) • 559-270-4291 (cell) • [email protected] Secondary Men’s Basketball Contact: Stephanie Juncker, Communications Intern 559-278-6187 (office) • 559-389-1901 (cell) • [email protected] GAME 12 • FRESNO STATE (5-6) AT UCLA (8-3) Dec. 22, 2012 • 8 p.m. PT • Los Angeles, Calif. - Pauley Pavilion (13,800) TV: Pac-12 Networks (Paul Sunderland & Don MacLean) Radio: KMJ 580 AM (Paul Loeffler & Randy Rosenbloom) Series record: UCLA leads 6-0 (overall) and 5-0 (FS road games) Last Meeting: UCLA 110, Fresno State 89 - Dec. 27, 1990 (Los Angeles, Calif.) FRESNO STATE UCLA TV VIEWING INFO: ABOUT THE UCLA BRUINS The Pac-12 Network is available in Fresno on Comcast Ch. 434 and Dish The UCLA Bruins are 8-3 this season and in the middle of a six-game TV Ch. 413. No other provider in Fresno carries the Pac-12 Network. homestand in the New Pauley Pavilion. UCLA head coach Ben Howland is in his 10th season and has guided the Bruins to the NCAA tournament BULLDOG BONES in six of nine seasons. The Bruins are led by superstar freshmen Jordan • This is the seventh meeting between Fresno State and UCLA. Adams and Shabazz Muhammad who have been the top scorers in nine • Fresno State has held each of its last six opponents to under 60 points. of their 11 games this fall. Muhammad, the 2012 Naismith Boys’ High • This season, MW teams are a nation-best 73-18 in non-conference School Player of the Year, leads the team in scoring with 17.8 ppg and adds games, with seven of the losses to opponents ranked in the Top 25. -

WN90N COUNT/, ALAZAMA MIL IZAOCBK Nbmlhiek

,1 WN90N COUNT/, ALAZAMA MIL IZAOCBK NBMlHieK lists: »s Sillssslssi siissSS si MARCH 2003 PRISON CAMPS Blue vs. Gray by Peggy Shaw The Civil War gave a new meaning to the term "Prisoner of War". Never before had there such a large number of soldiers held in an area; filled to such extreme over capacity. In 1861, the Confederate Army fired on Fort Sumter. Under the command of Gen. Pierce Beauregard, prisoners were paroled on their honor not to return to battle. He allowed the Union Soldiers to vacate Fort Sumter and take all the arms and personal belongings they could carry. He allowed paroled soldiers to give 100 gun salute to the American Flag before their departure. Gen. Beauregard had been a student of Maj. Anderson, commander at Fort Sumter, at West Point, and serving as Anderson's assistant after graduation. In July of 1862, Representatives Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill (Confederate) and Gen. Maj. John H. Dix (Union) held negotiations for prisoner exchanges. They agreed that first year officers would be allowed to return to their units. Officers were to be traded rank for rank and enlisted men exchanges were similar. Both incurred that all prisoners were to treated humanly, and the injured cared for just as those of the regular army. The war continued and the exchange system started to break down. Both sides began arguing with one another over alleged violations of parole agreements. Ulysses S. Grant stated, "Exchanging prisoners only prolongs the war. The war would be won only when the confederates could not replace their men as they lost them due to death, injury or capture". -

Confedera Cy

TheThe SourceSource Teaching with Primary Sources at Eastern Illinois University Reasons behind war are complex and there is rarely only one issue causing conflict. The Civil War is no different, there had been disagreements between the North and South for years. Slavery is considered the main reason for the Civil War and while the major issue, it was not the only one. The North and South had different economies. The North was moving towards the industrial revolution where factories used paid labor.1 The South was based in agriculture where crops, especially cotton, were profitable. Cotton was sold to mills in England and returned to the United States as manufactured goods.1 The North was able to produce many of these same items and northern politicians passed heavy taxes on imported goods trying to force the South to buy northern goods.1 These taxes seemed unfair to southerners. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed, allowing new states in the west to decide if they would be free or slave states. If either side could bring new states with the same beliefs, into the Union they would have more representation in government.1 Citizens of the southern states believed the rights of individual states had priority over federal laws. In 1859, at Cooper Union in New York City, Abraham Lincoln gave a speech outlining his policy at the time on slavery, “We must not disturb slavery in the states where it exists, because the Constitution, and the peace of the country both forbid us.”3 Lincoln opposed slavery and the prospect of the western states becoming slave states. -

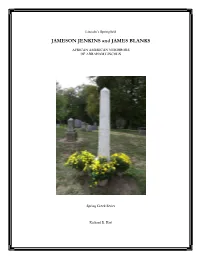

JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS

Lincoln’s Springfield JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Jameson Jenkins’ Certificate of Freedom 1 Recorded With the Recorder of Deeds of Sangamon County, Illinois on March 28, 1846 1 Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds, Deed Record Book 4, p. 21, Deed Book AA, pp. 284-285. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks Front Cover Photograph: Obelisk marker for graves of Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks in the “Colored Section” of Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. This photograph was taken on September 30, 2012, by Donna Catlin on the occasion of the rededication of the restored grave marker. Back Cover Photograph: Photograph looking north on Eighth Street toward the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson streets from the right of way in front of the lot where the house of Jameson Jenkins stood. Dedicated to Nellie Holland and Dorothy Spencer The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum is a not-for-profit organization founded in February, 2006, for the purpose of gathering, interpreting and exhibiting the history of Springfield and Central Illinois African Americans life in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We invite you to become a part of this important documentation of a people’s history through a membership or financial contribution. You will help tell the stories that create harmony, respect and understanding. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks: African American Neighbors of Abraham Lincoln Spring Creek Series. -

The United States Navy Looks at Its African American Crewmen, 1755-1955

“MANY OF THEM ARE AMONG MY BEST MEN”: THE UNITED STATES NAVY LOOKS AT ITS AFRICAN AMERICAN CREWMEN, 1755-1955 by MICHAEL SHAWN DAVIS B.A., Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 1991 M.A., Kansas State University, 1995 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2011 Abstract Historians of the integration of the American military and African American military participation have argued that the post-World War II period was the critical period for the integration of the U.S. Navy. This dissertation argues that World War II was “the” critical period for the integration of the Navy because, in addition to forcing the Navy to change its racial policy, the war altered the Navy’s attitudes towards its African American personnel. African Americans have a long history in the U.S. Navy. In the period between the French and Indian War and the Civil War, African Americans served in the Navy because whites would not. This is especially true of the peacetime service, where conditions, pay, and discipline dissuaded most whites from enlisting. During the Civil War, a substantial number of escaped slaves and other African Americans served. Reliance on racially integrated crews survived beyond the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, only to succumb to the principle of “separate but equal,” validated by the Supreme Court in the Plessy case (1896). As racial segregation took hold and the era of “Jim Crow” began, the Navy separated the races, a task completed by the time America entered World War I. -

South Street Journal News for and Serving: Grand Boulevard, Douglas, Oakland, Kenwood, Woodlawn, Washington Park, Hyde Park, Near South

THE PEOPLE P&PIR South Street Journal News for and serving: Grand Boulevard, Douglas, Oakland, Kenwood, Woodlawn, Washington Park, Hyde Park, Near South. Gao. Fuller Park Armour Sous Volumn 4 Number 5 February 28 - March 13„ 1997 esidenfs dismayed at Mid-South meetings Mayor's The State off the Washington Pk. Residents seeks Blue Ribbon Black Developers - outraged over Committee Empowerment Zone For over two years the fed million citywide,. Member [report alienates Meetineral Empowermeng reflectt Zones organization the bottom's of Mid Souts hou tdemolitio n at Troutman s meeting project has bexen looked at as say it's not enough. Bronzeville a major tool to rebuilt the Meetings throughout the Mid-South communi- city has address the "State of (Residents ties.The $100 million is to the Zone", from the West- Douglas- Approximately 80 people empower the people at the side to the South Side. | turned out for a report by Mayor Da- bottom of the economic The Community Work Iley's Blue Ribbon Committee on level to revitalize blighted shop onlxonomic Develop Bronzeville at the Illinois College of area through pubic/private ment JfcWED), a city wide Optometry auditorium on 32nd and In partnerships, using tax organization worked with diana in mid February. breads, loans and grants to organizations in winning the I The committee was appointed last low-income communities. national competitive award. lyear by the mayor to support commu- After meetings and meetings It has been part of the pro nity organizations initiatives in restor- the project has done a flip- cess for two years, providing Iing the "Bronzeville" community con- flop, favoring those at the technical assistance and fo jcept. -

Views of the Wigwam Convention: Letters from the Son of Lincoln's

Views of the Wigwam Convention: Letters from the Son of Lincoln’s 1856 Candidate JOHN T. ELLIFF Abraham Lincoln was nominated as a candidate for president on May 18, 1860, at the Republican convention in the Chicago Wigwam. On each of the three days before the roll calls, Cincinnati lawyer Nathan- iel C. McLean wrote letters from Chicago to his wife. He was neither a delegate nor a politician, but he was hoping for a deadlock that could result in nomination of his father, Associate Justice John McLean of the United States Supreme Court, to whom he referred affectionately as “the Judge.” He knew members of the Ohio delegation and gained inside knowledge of the deliberations of other state delegations. The candid observations he shared with his wife provide insights into the Wigwam convention from a newly available perspective.1 Justice McLean was a long-shot candidate from Ohio before whom Lincoln had practiced law in Illinois federal courtrooms.2 His long- standing presidential ambitions dated back to his service as postmas- ter general under Presidents Monroe and John Quincy Adams; he reluctantly accepted appointment to the Supreme Court by Andrew Jackson.3 When McLean sought the Whig presidential nomination 1. The letters were acquired recently by the Library of Congress where they were examined by the author. Letters from N. C. McLean to Mrs. N. C. McLean, May 15, 16, and 17, 1860, Nathaniel McLean Accession 23,652, Library of Congress. 2. “Of the many cases Lincoln handled in his twenty-four years at the bar, none was more important than Hurd v. -

The Washington Park Fireproof Warehouse and Its Architect, Argyle E

Published by the Hyde Park Historical Society The Washington Park Fireproof Warehouse and its Architect, Argyle E. Robinson By Leslie Hudson building in Hyde Park is turning one Ahundred years old this year. This building doesn't call much attention to itself. Driving by you might notice its bright orange awning but, unless you have rented a space within it, you may never have stopped to study the structure. But the next time you pass by, do stop-it's a unique and important building that deserves a good long look. It is the Hyde Park Self Storage building at 5155 Sou th Cottage Grove Avenue, originally called the Washington Park Fireproof Warehouse. Construction of the Washington Park Fireproof Warehouse began in 1905 during a period when many household storage buildings were being erected in Chicago, especially in its southern residential areas. Other warehouses built during this storage building heyday were once located nearby on Cottage Grove and Drexel Avenues. Although these other warehouses have been demolished, the Washington Park Fireproof Warehouse survives, and even continues to operate as a storage warehouse-its original function. And, thanks to the building's sturdy design and construction, and careful stewardship by its owners over the years, the building's original exterior has The Washington Park Fireproof Warehouse in 1905. The building doubled in size and remained intact. Today the building looks took on its current appearance with the north addition, built in 1907. almost identical to its appearance in ~8 2 ~ «0 photographs from the early 1900s. most noteworthy features of the building and was The Washington Park Warehouse was constructed probably the work of northern European immigrants, in two phases. -

Ira B. Sadler, Private, Co. A, 7 TX Infantry, C.S

Ira B. Sadler, Private, Co. A, 7 TX Infantry, C.S. 1841 June 20: Sadler was born. 1861 October 1: Enlisted in the C.S. Army in Marshall, TX. 1862 February 16: Captured at Fort Donelson. Sent to Camp Douglas, Chicago. March 12: Admitted to U.S.A. Prison Hosp., Camp Douglas, Chicago. Returned to “duty” on March 17th. July 9: Admitted to U.S.A. Prison Hosp., Camp Douglas, Chicago. Returned to “duty” on July 21st. August 1: Appeared on a roll of prisoners of war at Camp Douglas, Chicago, IL. September 6: Appeared on a roll of prisoners of war sent from Camp Douglas to Vicksburg to be exchanged. October 31: Company Muster Roll. Present. 1863 January to October: Company Muster Rolls. Present. November & December: Company Muster Roll. Present. Remarks “15 Rounds Ammunition.” 1864 January & February: Company Muster Roll. Present. Remarks “Reenlisted for the war.” April 19: Married Rebecca Chism in McLennan County, TX. April 28: Appeared on a roster of commissioned officers, Provisional Army Confederate States. Ira was listed as an Ensign. July 22: Wounded in the left hand during The Battle of Atlanta. July 24: Admitted to Ocmulgee Hospital in Macon, GA. August 15: Appears on a register of Floyd House and Ocmulgee Hospitals Macon, Ga.. Disease “G.S.W. left hand causing amputation of the thumb.” August 17: Furloughed till September 16. November 7: Appeared on a report of staff and acting staff officers serving in Cheatham’s Corps, Army of Tennessee in Tuscumbia Alabama. Remarks “Granbury’s Brigade” November 30: Fought in the Battle of Franklin under Granbury. -

Greater Little Zion Baptist Church 10185 Zion Drive Fairfax, VA 22032 Phone: 703-239-9111 Fax: 703-250-2676 Office Hours: 9:30 A.M

Greater Little Zion Baptist Church 10185 Zion Drive Fairfax, VA 22032 Phone: 703-239-9111 Fax: 703-250-2676 Office Hours: 9:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Email: [email protected] Website: www.glzbc.org Communion Sunday Sunday, November 18, 2018 2018 Theme: "The Year of the Warrior" Isaiah 59:17 & Ephesians 6:10-17 Church Vision: The vision of GLZBC is to reach the unsaved with the saving message of Jesus Christ. Matthew 28:19-20 Church Mission: The mission of GLZBC is to lead everyone to a full life of development in Christ. Luke 4:18-19 Rev. Dr. James T. Murphy, Jr., Pastor E-mail: [email protected] Worship on the Lord’s Day This is my Bible. I am what It says I am. I have what It says I have. I can do what It says I can do. Today I will 7:45 a.m. Service be taught the Word of God. I boldly confess that my mind is alert, my heart is receptive and I will never be the same. In Jesus’ name. Amen. Today’s Music Leaders Sermon Notes Musicians .…....... Bishop Paul Taylor and Minister Keith Exum Message Notes 7:45 a.m. Minister of Music .…...………….……… Brother Robert Fairchild Scripture (s): Sermon Text: Call to Worship ……………….……………………………………………….... Invocation ..……………………......……...….………..…………... Minister Musical Selection (2) ………………….…......................….… Church Choir The Spoken Word/Sermon ……………...... Rev. Dr. James T. Murphy, Jr. Sermon Title: "At the Table" Luke 22:14-23 Invitation to Salvation ………….……..….... Rev. Dr. James T. Murphy, Jr. Worship of Giving/Prayer …………..……...… Board of Directors/Deacons (Bring Prayer Request As Well With Offering) Welcoming of Visitors ….…...…………………………….