Doris Lessing. the Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and $19.25. Which She Added to the Golden Notebook, Protesting Against

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“A Small Voice for the Earth” – a Romantic and Green Reading of Doris Lessing's Shikasta

“A Small Voice for the Earth” – A Romantic and Green Reading of Doris Lessing’s Shikasta Riikka Siltaoja University of Tampere School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies English Philology Master’s Thesis December 2012 Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö SILTAOJA, RIIKKA: Ekokriittinen ja romanttinen luenta Doris Lessingin romaanista Shikasta Pro gradu-tutkielma, 73 sivua Syksy 2012 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Tutkielmassani tarkastelen Doris Lessingin science fiction-romaania Shikasta (1979) ekokriittisestä näkökulmasta. Pyrin myös osoittamaan sen yhteyden romanttisen luontokirjallisuuden ja pastoraalin perinteeseen. Doris Lessing on tullut tunnetuksi erityisesti vasemmistolaisena kirjailijana, mutta hän on myös tunnettu siitä, miten vaikea hänen töitään on kategorioida. Väitän tutkielmassani, että Shikastassa on havaittavissa paitsi Lessingin pettymys kommunismiin ja puoluepolitiikkaan, myös selkeä filosofinen siirtymä ’punaisesta vihreään’ politiikkaan. Ensin tarkastelen Shikastan sosialistisia piirteitä pohjautuen Terry Eagletonin etiikkaan teoksessa After Theory (2003), erityisesti suhteessa hänen käsitykseensä objektiivisuudesta ja Aristoteelisesta hyveestä, jotka ovat hänen moraalikäsityksensä perustana. Esitän, että Shikastan esittämä yhteiskuntamalli sekä moraalikäsitys ovat ideologialtaan utopistisen sosialistisia. Ne pohjautuvat erityisesti kollektiiviselle rakkaudelle, -

The Element of Life and Creation As It Lurks in Doris Lessing's the Golden Notebook

The Element of Life and Creation as it lurks in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook *Jitendra Dimri Ph.D.Research Scholar, Dept. of Humanities, NIT Raipur C.G. **Dr.Anoop Kumar Tiwari Asst. Professor, Dept of Humanities NIT Raipur C.G. & **Anil Manjhi, Ph.D.Research Scholar, Dept of Humanities, NIT Raipur C.G. Abstract Doris Lessing; the Nobel Laureate of literature 2007, is one of those most powerful and significant novelists of the twentieth and twenty first century who dominated the post- war English and has written on various themes like feminism, the battle of the sexes, individuals in search of wholeness, cultural clashes, racial discrimination and the dangers of science and technology. Apart from contributing to the contemporary themes, she has also placed herself successfully to be a power bearer of life and creation as an author. It is an author who gives life and sense to his or her characters literally and while doing so transfers some events, experiences and characteristics of his or her own self to characters, which exists in the work either in lurking or exposed form and The Golden Notebook is one of the masterpieces of Lessing in which such element of life and creation lurks till unveiled and this paper is an attempt for the same. Keywords: Author, character, life and creation, lurking. www.ijellh.com 218 A writer‟s works have a deep impact of his/her personal experiences. In his/her work, a writer can present the situations or characters which s/he faced or met. The impact of their life can be seen on their works as Lessing writes, “First novels are usually autobiographical” (WS 14). -

Doris Lessing At

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS Shikasta presents a revised version of Earth in the titular planet. Reports written by colonial servants of the galactic empire Canopus, historical texts, accounts and case studies create a diffuse narrative. There are echoes of Southern Rhodesia, where white settlers had seeded themselves at the end of the nineteenth century: Lessing described it as “a very nasty little police state”. For instance, native people on Rohanda (a col ony that reappears in the more sociological BILD VIA GETTY SCHIFFER-FUCHS/ULLSTEIN third book, The Sirian Experiments) are subjected to “an allout booster, TopLevel Priority, ForcedGrowth Plan”, an explicit imperialist project. The second book, The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five, set in ‘zones’ of civilization circling Shikasta, is an intense and explosive explo ration of gender dynamics and stereotypical interactions between men and women. In The Making of the Representative for Planet 8, Lessing examines human behaviour in the face of a brutal ice age. The inhabitants of Planet 8 must ultimately accept climate based extinction, aided by a Canopean Doris Lessing, photographed in 1990. official, Doeg. This mythic apocalyptic par able was influenced by Anna Kavan’s 1967 FICTION scifi novel Ice, as well as the death of British explorer Robert Falcon Scott in Antarctica in 1912, which fascinated Lessing. Towards the end, echoing current perceptions of plane Doris Lessing at 100: tary fragility, an inhabitant notes that “what we were seeing now with our new eyes was that all the planet had become a fine frail web roving time and space or lattice, with the spaces held there between the patterns of the atoms”. -

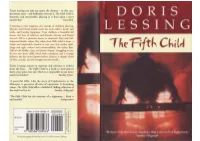

Lessing the Fifth Child.Pdf

Doris Lessing was born of British parents in Persia (now Iran) in 1919 and was taken to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) when she was five. She spent her childhood on a large farm there and first came to England in 1949. She brought with her the manuscript of her first novel, The Grass is Singing, which was published in 1950 with outstanding success in Britain, in America, and in ten European countries. Since then her international repu- tation not only as a novelist but as a non-fiction and short story writer has flourished. For her collection of short novels, Five, she was honoured with the 1954 Somerset Maugham Award. She was awarded the Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 1981, and the German Federal Republic Shakespeare Prize of 1982. Among her other celebrated novels are The Golden Notebook, The Summer Before the Dark, Memoirs of a Survivor and the five volume Children of Violence series. Her short stories have been collected in a number of volumes, including To Room Nineteen and The Temptation of Jack Orkney; while her African stories appear in This Was the Old Chief's Country and The Sun Between Their Feet. Shikasta, the first in a series of five novels with the overall title of Canopus in Argos: Archives, was published in 1979. Her novel The Good Terrorist won the W. H. Smith Literary Award for 1985, and the Mondello Prize in Italy that year. The Fifth Child won the Grinzane Cavour Prize in Italy, an award voted on by students in their final year at school. -

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Lessing, Doris, 1919-2013 Title: Doris Lessing Papers Dates: 1943-2008, undated Extent: 76 document boxes (31.92 linear feet), 1 oversize folder (osf), 9 galley files (gf) Abstract: The Doris Lessing Papers document the English author's creative life through artwork, clippings, correspondence, galley proofs, journal pages, libretti, manuscripts, notes, objects, page proofs, photographs, play scripts, printed material, screenplays, and sound recordings. The focus of the collection is on her professional rather than personal life. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-2460 Language: Predominantly English , with some (mostly printed) material in Dutch, French, German, Japanese, Norwegian , Portuguese, and Spanish Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Acquisition: Purchases, 1999 (R14457, R16015); 2015 (15-01-012-P) Processed by: Processed by: Liz Murray, 1999; Richard Workman, 2016 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Lessing, Doris, 1919-2013 Manuscript Collection MS-2460 Biographical Sketch Doris Lessing was born in 1919 to English parents who were resident in Persia (now Iran) at the time. Her father, Alfred Tayler, was a bank employee. The family lived in Persia until Doris was five years old, when her father bought a farm in what was then Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Lessing spent the next 25 years in Africa, marrying and divorcing twice and having three children before she took her youngest child, Peter, and moved to England in 1949. The next year her first novel, The Grass Is Singing, was published. She supported herself and her son by writing poetry, articles, stage plays, screenplays for television and film, short stories, and novels, including the Children of Violence novel series (1952-1969). -

Doris Lessing's the Grass Is Singing

International Journal of English and literature Vol. 4(1), pp. 11-16, January 2013 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ijel DOI: 10.5897/IJEL11.119 ISSN 2141-2626 ©2013 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Doris Lessing’s The Grass is Singing: Anatomy of a female psyche in the midst of gender, race and class barrier Mohammad Kaosar Ahmed Department of English Language and Literature, International Islamic University Chittagong, Dhaka Campus, Bangladesh. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 20 December, 2012 One of the founder mothers of feminism, Doris Lessing made her debut as a novelist with The Grass is Singing (1950). The novel examines the relationship between Mary Turner- a white farmer’s wife and her black servant. The novel does not unswervingly explore the feminist causes. Still, Lessing’s portrayal of Mary Turner warrants a closer examination because of the unique perspective Lessing brings to unfold the female psyche in the midst of gender, race and class barrier. Key words: Gender, psyche, race, sexism. INTRODUCTION The Grass is Singing is a tale of subjection of a woman 1952), a semiautobiographical five-novel series featuring who was defeated and thwarted by the bullying of race, the character Martha Quest (Rosen, 1978), reflects her gender and other social discriminations. Mary Turner, the African experience and is among her most substantial victim of such oppression, is unlike the other characters works. The Golden Notebook (2007), her most widely of Lessing, as she was never been given any freedom. read novel, is a feminist classic. Her masterful short Isolation, mental and economic sterility and emotional stories are published in several collections. -

D.H. Lawrence and Doris Lessing

1 Proposal for Collaborative Session MLA Vancouver 2105 Panel Organizer: Nancy L. Paxton, Dept. of English, Northern Arizona University This proposal was developed in collaboration with Alice Ridout, current president of the Doris Lessing Society, and Holly Laird, current president of the D. H. Lawrence Society of North America. It is a revision of the proposal for a collaborative session submitted by Holly Laird for MLA ‘14. (See MLA Reference number A067A) Description of Session In recognition of Doris Lessing’s death on Nov. 17, 2013, the Doris Lessing Society and the D. H. Lawrence Society of North America propose a collaborative session to compare these two writers’ complex narrative responses to trauma, war, and madness. Much of the earlier scholarship comparing Lawrence’s and Lessing’s writing focused on their representations of gender identity, sexuality, or conflicts in their views of feminism. Mark Spilka’s “The Battle of the Sexes” (Contemporary Literature, 1975) and Paul Schlueter’s The Novels of Doris Lessing (1973) are two examples, among many. Inspired in part by Doris Lessing’s preface to the 2006 Penguin edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and her 2002 article on Lawrence’s The Fox for The New York Review of Books, this session will explore how Lawrence and Lessing responded in their fiction to the traumas of war, displacement, and madness. D. H. Lawrence was profoundly traumatized by the death and destruction of World War I and by the banning of The Rainbow in 1915; his subsequent writing presents evidence of these traumas, as Mark Kinkead-Weekes, Jill Franks, and many others have shown. -

Science-Fictionalization of Trauma in the Works of Doris Lessing

Science-fictionalization of trauma in the works of Doris Lessing Paulina Kamińska (Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce) Abstract. The aim of this paper is to show Doris Lessing’s literary endeavors into the world of science fiction from the perspective of trauma theory. Lessing’s preoccupation with modern reality is clearly visible in even the most experimental of her later narratives. Trauma theory finds justification for setting narratives in another dimension: science fiction mode allows for multiple perspectives on the same events, as well as a faithful representation of psychological states experienced by the protagonists. This paper traces science-fictional developments in Lessing’s fiction from the watershed Four-Gated City to the Canopus in Argos: Archives series: Lessing’s first literary adventure fully set in a space-fictional dimension. Key words: science fiction, traumatic experience, working through 1. INTRODUCTION Doris Lessing has been noted for her interest in the “big ideas” such as “the end of imperialism, the hope and failure of communism, the threat of nuclear disaster and ecocide” (Greene 1994, 1), or “colonialism, politics, the roles of women in relation to men and to each other” (Whittaker 1988, 4), to name a few. Such commitment to serious social issues naturally led her to fascination with realism, which is an acknowledged primary mode of representation in her early writing such as The Grass Is Singing or the Children of Violence series. However, what has also been frequently noted and criticized is Lessing‟s transgression of the conventional realist form. Already in her early fiction Jeanette King (1989) finds “tensions between the novel‟s themes and the realist form” ( 14), which are demonstrable by the lack of closure in The Grass Is Singing (4), or an unusual ending to the bildungsroman narrative in the story of Martha Quest. -

The Theme of Alienation in the Major Novels of Doris Lessing

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 6, Issue 1, January 2018, PP 40-42 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0601006 www.arcjournals.org The Theme of Alienation in the Major Novels of Doris Lessing Narendra Kumar Singh1*, Dr. Chhaya Jain2 1Research Scholar, C.S.J.M. University, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh 2Asso.Prof. Dept.of English, V.S.S.D.College, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh *Corresponding Author: Narendra Kumar Singh, Research Scholar, C.S.J.M. University, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh Abstract : This paper aims to conduct a detailed thematic analysis of Doris Lessing’s major novels. The term alienation is currently used to describe objectively observable state of separateness occurring in human group. An older usages viewed alienation as a subjective, an individual condition. It is defined variously in different eras. It depends on the ideologies and classificatory system widespread at the time. People, who are alienated, will often reject loved ones or society and feel distant. Alienation, a sociological concept developed by several classical and contemporary theorists is “A condition in social relationship reflected by a low degree of integration or common values and a high degree of distance or isolation between individuals.” In short, the alienation is the inconsistency between man and attitude. Such inconsistency can be frequently seen in the novels of Lessing. Many writers have made significant contribution on the theme of alienation. A lot of research work has been done on the very theme with reference to different poets, dramatists and fiction writers but the theme of alienation and estrangement in the novels of Doris Lessing is yet to be explored. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at~the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9111699 Fluid bodies: Narrative disruption and layering in the novels of Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison and Margaret Atwood Epstein, Grace Ann, Ph.D. -

<I>Descent Into Hell</I> and Doris Lessing's

Volume 4 Number 1 Article 4 9-15-1976 A Briefing for Briefing: Charles Williams' Descent Into Hell and Doris Lessing's Briefing orF a Descent into Hell Ellen Cronan Rose Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Ellen Cronan (1976) "A Briefing for Briefing: Charles Williams' Descent Into Hell and Doris Lessing's Briefing orF a Descent into Hell," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Asserts that “Doris Lessing’s naming of her book and its protagonist was both intentional and ironic, and that it acknowledges her indebtedness to the form of Williams’ fiction and her [...] futile gesture toward the Romantic amalgam of appearance and reality.” Additional Keywords Lessing, Doris. -

Doris Lessing's «Passage» to England

Universitas Tarraconensis. Revista de Filologia, núm. 11, 1987 Publicacions Universitat Rovira i Virgili · ISSN 2604-3432 · https://revistes.urv.cat/index.php/utf DORIS LESSING'S «PASSAGE» TO ENGLAND Cristina ANDREU It is the aim of this paper to consider some of the social and biographical aspects that form the background to Doris Lessing's literary career. Her political commitment, her rejection of academicism and conventional education, the constant shifts of her fiction, appear less confusing when we read about Lessing's experience in Africa, a long period of her life which we have chosen to call her «passage» to England. Doris Lessing arrived in England, from South Africa, in 1949. This year is an important landmark in her novelistic career since she was able to fulfil her desire of becoming a writer. Her first novel The Grass Is Sin ging, which she had written in Africa, was published in 1950. The book was a success of acceptance and criticism; something quite amazing for a woman writer —especially given the subject-matter of the novel. But what had happened before that? Who was this woman coming from a British colony who dared to take such a tough stand against British colonialism and the morals of white civilization? Answers to these questions can be traced in her following novels, especially the Children of Violence series (1952-1969), which provide a rich biographical source as well as a moral portrait of western civilization and a historical document of pre- and post-Second World War life in white dominated Southern Rhodesia. Doris Lessing brought her African experience and African writing to London at a timely moment.