Global Knowledge Futures: Articulating the Emergence of a New Meta-Level Field1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics of Designing Visions of the Future

DOI:10.6531/JFS.201903_23(3).0003 ARTICLE .23 Politics of Designing Visions of the Future Ramia Mazé Aalto University Finland Abstract Scenarios for policy and the public are increasingly given form by designers. For design, this means ideas about the future – futurity – is at stake, particularly in genres of ‘concept’, ‘critical’ and ‘persuasive’ design. While critical approaches are present in futures studies and political philosophy, design assumptions and preferences are typically not explicit, including gender norms, socio-ecological practices and power structures. Calling for further studies of the politics of design visions, I outline possible approaches and elaborate through the example ‘Switch! Energy Futures’. I reflect upon how competing visions and politics of sustainability become explicit through our process, aesthetics and stakeholders. Keywords: Futures Studies, Design, Design Theory, Visualization, Scenarios, Political Philosophy. Introduction The future – indeed, temporality – has only entered substantially into design discourse relatively recently. Design and other disciplines such as architecture, geography and geology have long been preoccupied with space rather than with time (Grosz, 1999; Mazé, 2007). Today, however, ideas about the future – or, in philosopher Elizabeth Grosz’ terms, futurity – is stake in many design arguments and practices. Assumptions about time, progress and futurity underlie popular rhetoric concerning ‘change’, ‘progress’, ‘transformation’ and ‘transition’, and design, along with many disciplines, is affected by the increasing hegemony of values framed as ‘newness’ and ‘innovation’ (e.g. Wakeford, 2014). Beyond mere rhetoric, design research and practice must further develop its approaches to futurity. Indeed, the future is itself might be conceived as a design problem (Reeves, Goulden, & Dingwall, 2016). -

Implication of Two New Paradigms for Futures Studies1 Éva HIDEG

Implication of Two New Paradigms for Futures Studies 1 Éva HIDEG Abstract The paper considers the emergence of two recent perspectives in futures work. One is evolutionary futures studies. The other is critical futures studies. After describing aspects of each, the paper considers them as alternative rival paradigms in relation to criteria that include: the role of the human being as a subject, the role of interpretation and differences in methodological premises. It concludes that both have contributed to the development of futures methods but that a number of theoretical and methodological problems still remain unsolved. 1. Antecedents and main theoretical-methodological problems What has most characterised the road covered by studies of futures up to the 1980s was its emergence as an independent and structured field of science and as an independent sphere of social activity. Despite the fact that the theory and methodology of futures research had crystallised and solidified, the studies of futures had by no means become united. The paradigmatic differences interpreted according to Kuhn remained palpable 2. This was most detectable in the cultivation of two differing systems of approaches, namely in futures research, which adopts the criteria of classical science, and in futures studi es , which is more culture-based. Futures research, which moulds the particular criteria of science it wishes to adhere to more and more, worked on developing and adapting new methods and on uniformly solidifying the process of forecasting in different areas. Futures studies, however, interpreted the determination of the future, the future-shaping role of culture and the methodology of futures studies through the filter of research into culture. -

Department of Futures Studies

DEPARTMENT OF FUTURES STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF KERALA M.Phil PROGRAMME IN FUTURES STUDIES SYLLABUS (Under Credit and Semester System w.e.f. 2016 Admissions) UNIVERSITY OF KERALA DEPARTMENT OF FUTURES STUDIES M.Phil Programme in Futures Studies Aim: The M.Phil Programme in Futures Studies aims to make the students to conceive and constitute objects for research that belong to interdisciplinary areas with special emphasis on science, technology and its relationship with society with a futuristic outlook. It also intends to equip the students with forecasting and futuristic problem solving methods in their basic areas of specialization. Objectives To introduce the students to advanced areas of research in their basic domain with a futuristic outlook. To make the students competent in literature collection pertaining to his/her study area. To make the students to do independent field work and data collection. To prepare the students for undertaking analysis with the help of computational tools and softwares. To prepare the students to undertake serious research and train the students in better scientific communication. Structure of the Programme Semester Course Code Name of the Course Number of No. Credits FUS-711 Interdisciplinary Research & Research 4 Methodology FUS-712 Scientific Computing and Forecasting 4 FUS-713(i) Technological Futures, Forecasting and 4 Assessment FUS-713(ii) Computational Chemistry 4 FUS-713(iii) Molecular Modeling and Molecular Dynamics 4 I FUS-713(iv) Optimization Techniques 4 FUS-713(v) Nonlinear Dynamics and -

Futures-Thinking Skills to Students and Educators Around the World and to Inspire Them to Influence Their Futures

Teaching about the Future Peter Bishop Sacramento CA 30 October 2030 We teach the future as we do the past. Our ASPIRATION is that every student is prepared to navigate an uncertain world and has the agency to imagine and create their preferred future. Our MISSION is to teach futures-thinking skills to students and educators around the world and to inspire them to influence their futures. We teach the future as we do the past. Today’s Purpose Enroll you in the campaign to accomplish something of significance “My name is Harvey Milk... And I am here to recruit you.” -- Milk, the movie, 2008 We teach the future as we do the past. The Invention of “the Future” • Ancient techniques, Delphic Oracle • Eschatology, End times • Enlightenment (Industrial revolution) – Sebastien Mercier, L’Ann 2440 (1770) – Marquis de Condorcet, Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind (1778) – Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) • Science fiction – Jules Verne (1865), H.G. Wells (1898) • Trends – William Ogburn (1933), H.G. Wells (1901) • Theory (1950s) – Herman Kahn, RAND Corp – Fred Polak, Bertrand de Jouvenel, Gaston Berger We teach the future as well as the past. The Professionalization of the Future • Forecasting – from the Delphic Oracle to… – Trend extrapolation: William Ogburn, Recent Social Trends, 1933 – Econometrics: Lawrence Klein, Wharton Econometric Model, 1969 • Planning – from L’Enfant, Wash DC to… – Budget planning: Programming, Planning, Budgeting Systems (PPBS), 1961 – Urban planning: American Planning Assoc, 1978 – Strategic planning: Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy, 1980 We teach the future as well as the past. -

Futures Studies: Theories and Methods Sohail Inayatullah >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

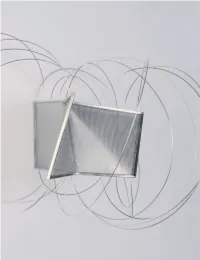

Futures Studies: Theories and Methods Sohail Inayatullah >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> INTRODUCTION Futures studies is the systematic study of possible, probable and preferable futures including the worldviews and myths that underlie each future. In the last fifty or so years, the study of the future has moved from predicting the future to mapping alternative futures to shaping desired futures, both at external collective levels and inner individual levels (Masini 1993; Bell 1996; Amara 1981; Sardar 1999; Inayatullah 2000; Saul 2001). During this period, futures studies has moved from focusing on the external objective world to a layered approach wherein how one sees the world actually shapes the future one sees (Inayatullah 2002). In this critical futures approach — the poststructural turn — the external world is informed by the inner and, crucially, a person’s inner world is informed by the reality of the external. While many embrace futures studies so as to reduce risk, to avoid negative futures, particularly the worst case, others actively move to creating desired futures, positive visions of the future (Masini 1983). The identification of alternative futures is thus a fluid dance of structure (the weights of history) and agency (the capacity to influence the world and create desired futures). As the world has become increasingly risky — at least in perception, if not in fact — futures studies has been eagerly adopted by executive leadership teams and planning departments in organizations, institutions and nations throughout the world. While futures studies sits comfortably as an executive function by providing the big picture, there Blanca Muñoz, Campo magnético triple (detail) remain tangible tensions between the planning and futures frameworks. -

Entropy and Immortality

ARTICLE .39 Entropy and Immortality Charles Tandy Fooyin University Taiwan Abstract In part one (of two parts) I show that any purely physical-scientific account of reality must be deficient. Instead, I present a general-ontological framework that should prove fruitful when discussing or resolving philosophic controversies; indeed, I show that the paradigm readily resolves the controversy "Why is there something rather than nothing?" In part two, now informed by the previously established general ontology, I explore the issue of immor- tality. The analysis leads me to make this claim: Entropy is a fake. Apparently the physical-scientific resurrec- tion of all dead persons is our ethically-required common-task. Suspended-animation, superfast-rocketry, and seg-communities (Self-sufficient Extra-terrestrial Green-habitat communities, or O'Neill communities) are identified as important first steps. Keywords: all/everything, biostasis/suspended animation, Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov, Kurt Gödel, knowl- edge, mind, Gerard K. O'Neill, ontology, paradigm, time travel Introduction: Caveat Emptor Futures studies or futuristic studies (or futuristics) is a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary enterprise. I myself happen to be both philosopher and futurist. Since most futurists and most read- ers of this article are not philosophers, I may need to briefly explain my style of presentation. Assertion, inference, and argument – used in a concerted, deliberative, disciplined way – are com- mon tools of philosophers past and present. Accordingly, a philosopher may sound unusually sure of herself for the purpose of professional discourse. In such way two philosophers may seem to be bitter enemies in their published works. But outside the publication world, the two may in fact be the closest of friends. -

Futures Studies Jim Dator Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies Department of Political Science University of Hawaii at Manoa

Futures Studies Jim Dator Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies Department of Political Science University of Hawaii at Manoa Published as "Futures Studies ," in William Sims Bainbridge, ed., Leadership in Science and Technology. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Reference Series, 2011, Vol. 1, Chapter Four, pp. 32-40. Who Are Futurists, and What Do They Do? It is a common cliché to assert that all humans are futurists. Without a doubt a distinct human capability is to dream, scheme, plan ahead, and then create the technologies necessary to strive for and perhaps attain the dream. But many other species do so as well. Humans are not unique in this except for the scope of their dreams and the power of their technologies. But if all humans are futurists, then humans are also chemists, physicists, historians, priests and everything else. Yet we still needed physicists and engineers to get to the Moon in spite of eons of dreams and stories about space flight, and it seems even the most fundamental and protestant among us still feel the need for some kind of priests to keep us out of hell, and so it probably is the case that futurists can be useful in helping us think more clearly about the causes and consequences of our dreams and fears about the futures. No one can accurately "predict" exactly what "the future" of anything of consequence will be, though there are many charlatans who say they can, and who are paid big bucks for their "predictions", almost all of which prove not only to be false, but dangerously so. -

Counseling and the Future: Concepts, Issues, and Strategies. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services, Ann Arbor, Mich

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 195 922 CG 014 939 AUTHOR Hays, Donald G. TITLE Counseling and the Future: Concepts, Issues, and Strategies. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services, Ann Arbor, Mich. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 81 CONTRACT 400-78-0005 NOTE 46p. AVAILABLE FROMERIC Counseling and Personnel Services Clearinghouse, 2108 School of Education, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 ($6.001. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Counseling: *Counseling Techniques: Counselor Attitudes: Counselor client Relationship; *Counselor Role; Counselors: *Futures (of Society): Helping Relationship: *Long Range Planning; Models: Prediction: *Social Indicators; State of the Art Reviews; Trend Analysis ABSTRACT Futurists and counselors both deal with the concept of change. This monograph examines some strategies counselorscan use to help themselves adopt a future orientation and to assist their counselees it meeting the future confidently. The writings of Cornish, Fletcher and Conboy bring some focus to concepts and dimensions held by futurists and whichare related to the counseling profession. It is suggested that counselors hold a set of beliefs (e.g., Change over time is an integral part of understanding the future) in order to aid counselees in developing guiding images about their personal and social futures. Some problems need to bedealt with in this context, including: economics, politics and government, science and.toachology, individuals and society. Several strategies are discussed for teaching the futurist / counselors' beliefs: (1) a wheel of consequences is used to illustratea holistic approach to the universe: (2)a "Backward Think" approach illustrates the "integralnesse of change: (3) image-building of the future is examined through a "what if?" approach:(4) alterliatiVe choices are highlighted using a decision tree; and (5)purposeful action using a scenario or a future timetable is discussed. -

The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies 2020

Purchase link: https://www.apf.org/store/ViewProduct.aspx?id=16603386 The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies 2020 Editors Richard Slaughter & Andy Hines Washington, DC, USA Brisbane, Australia Copyright © 2020 Association of Professional Futurists and Foresight International All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies 2020 is edited by Richard A. Slaughter and Andy Hines. For questions regarding this publication, please write [email protected]. This book is licensed for your personal study only. It may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use, then please visit https://www.apf.org/ and buy your own copy. Thank you for respecting the work of these authors and editors. For details of the earlier 5-volume USB Legacy Edition of the KBFS please go to: https://foresightinternational.com.au/kbfs/ To purchase go to: https://foresightinternational.com.au/shop/usb/knowledge-base-of-future-studies-usb/ Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-0-9857619-3-6 (print) ISBN: 978-0-9857619-2-9 (ebook) The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies 2020 CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................................... -

1.2 Futures Studies As Applied Knowledge Jim Dator This Paper

1.2 Futures studies as applied knowledge Jim Dator This paper was derived from one originally prepared for the First World Futures-Creating Seminar "Renewing Community as Sustainable Global Village," organized by Kaoru Yamaguchi, August 16-19, 1993, Goshiki-cho, Awaji Island, Japan Published in Richard Slaughter, ed., New Thinking for a New Millennium. London: Routledge, 1996, and in Kaoru Yamaguchi, ed., Sustainable Global Communities in the Information Age. Visions from Futures Studies. London: Adamantine Press, 1997. FUTURES STUDIES, ACADEMIA, AND DECISION MAKING At the present time, futures studies is to modern academia and societal decision making what Science was to academia and societal decision making in the late Middle Ages. Because of this, I am no more likely to get most successful academicians, politicians, and business persons to take futures studies seriously (and thus to help them and their organizations to think and act more helpfully about the future), than Copernicus was in getting the powers that were in his time to recognize that the earth isn't the center of the universe. Because futures studies is not like other established fields in academia, it is constantly being misunderstood and misused. The traditional academic world in the West (as revealed by the organization of its major universities--especially those of the United States) knows of only five kinds of academic pursuits: First and foremost are the so-called 'natural' sciences (disciplines like physics, astronomy, chemistry, and biology with their necessary handmaiden, mathematics; more recently also earth, atmospheric and marine sciences, and their newer handmaiden, computer and information science). These are the 'real' sciences, based (by and large) on positivistic, reductionistic methods and assumptions. -

A Stitch in Time? Realising the Value of Futures and Foresight

Funded by A stitch in time? Realising the value of futures and foresight Adanna Shallowe, Aleksandra Szymczyk, Ella Firebrace, Ian Burbidge and James Morrison A stitch in time Realising the value of futures and foresight Adanna Shallowe Aleksandra Szymczyk Ella Firebrace Ian Burbidge James Morrison October 2020 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Acknowledgments Contents Page no. We thank our interviewees, listed in About the authors Appendix B, who unfailingly gave up i. About us 2 their time and energy to answer our We all have an interest in foresight often naive questions around the topic and futures and how change happens. and openly shared with us the benefit of Adanna Shallowe has a background in ii. Foreword by Prof Chris Fox 4 their expertise, insights and hindsights, international relations and development often introducing us to others who and is responsible for harnessing iii. Notes on reading this report 6 offered expertise in different aspects global insights in the RSA’s research. of the field. We appreciate you all for Aleksandra Szymczyk is a research iv. Foreword by Matthew Taylor 7 engaging so openly with us. Many of our associate at Manchester Metropolitan interviewees were also RSA Fellows, University’s Policy Evaluation and 1. Introduction 8 confirming to us what a rich body of Research Unit with a background in thought and experience there is in the social anthropology. Ella Firebrace 2. Executive summary 11 Fellowship. In the interests of reciprocity has a background in international we will endeavour to support this group migration and works across a range to connect and convene as appropriate, of RSA programmes including Cities 3. -

History of the World Futures Studies Federation, April 2008

A Brief History of the World Futures Studies Federation Background for the Spring 2008 Refreshing Exercise by Roger Caldwell and Ruben Nelson Revised May 11, 2008 (Original April 15, 2008) The World Futures Studies Federation (the Federation) membership is engaging in a series of questions during our “refreshing exercise” for assessing the state of the Federation. This brief history is in two parts: 1) three pages of brief descriptions of the formation, activities, and recent events of the Federation, and 2) four pages of brief excerpts from the June 2005 issue of Futures, which is entirely devoted to 10 papers and which give various perspectives on the history and significance of the Federation. We are Operating in Crisis Mode The Federation has been faced with some difficult operating conditions in recent years and this history is intended to be brief but to highlight material so all members have some reminders of times past. Some examples of the changes include: 1) the world had changed since the formation 35 years ago ( more futures organizations, new ways of communicating, and constraints on travel and available time for members, 2) Federation changes were made at the Turku World Conference in 1993, including a revision in the constitution and a modification in the selection of Executive Council members (the executive council replacements were previously named by the executive council, rather than through the current election process), 3) the operational difficulties of managing the Federation have increased (bookkeeping, web support, organizations that contribute support or meeting sponsorships), and 4) people sense there is a problem ( a series of resignations of Executive Board members, a series of critical concerns identified by the President, and a general organizational malaise within the membership).