The Holden-Marolt Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TO: Aspen Historic Preservation Commission Frovf: Amy Guthrie, Historic Preservation Officer

{@s7 EMORAI\DUM TO: Aspen Historic Preservation Commission fROVf: Amy Guthrie, Historic Preservation Officer RE: Ute Cemetery National RegisterNomination DATE: July 11,2001 SUMMARY: Please review and be prepared to comment on the attached National Register nomination, just completed for Ute Cemetery. We received a grant to do this project. The author of the nomination is also under contract to complete a management plan for the cemetery. He, along with a small team of people experienced in historic landscapes and conservation of grave markers, will deliver their suggestions for better stewardship of the cemetery in September. The City plans to undertake any necessary restoration work in Spring 2002. USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 4 UTE CEMETERY PITKIN COUNTY. COLORADO Name of Property CountY and State 1n Aannrnnhinol l)ata Acreage of Property 4.67 acres UTM References (Place additional UTM references on a continuation sheet) 2 1 13 343s00 4338400 - Zone Easting Northing %16- A-tns Nortffis z A Jee continuation sheet Verbal Boundary Description (Describe the borndaries of the property on a continuation sheet ) Bounda ry Justification (Explain wtry the boundaries were selected on a continuation sheet.) 1 1. Form Prepared Bv NAME/titIE RON SLADEK. PRESIDENT organization TATANKA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATES. lNC. date 28 JUNE 2001 street & number P.0. BOX 1909 telephone 970 / 229-9704 city or town stateg ziP code .80522 Additional Documentation Submit the fdloaing items with $e completed form: Continuation Sheets Maps A USGS map (7.5 or l5 minute series) indicating the property's location. A Sketch mapfor historic districts and properties having large acreage or numerous resources. -

M COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF

/!?"' . P »!» n .--. - •" - I A ^UL. STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Colorado COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Pitkin INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) UN 1 2 W5 COMMON: pitkin county Courthouse AND/OR HISTORIC: pitkin County courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Aspen STATE Colorado 08 pitkin 051 BliMsfiiiiiiQi CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSH.P STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District jg Building 89 Public Public Acquisition: (X) Occupied Yes: ,, .1 CH Restricted Q Site Q Structure D Private Q In Process Unoccupied r— i D • d— Unrestricted D Object D Both [~] Being Considered |-j p reservat|on w in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [~1 Agricultural ps| Government | | Park Q Commercial CD Industrial ( | Private Residence C] Educational 1 1 Military [ | Religious Q Entertainment l~l Museum [~1 Scientific OWNER'S NAME-. ffffyws Pitkin county, Colorado Colorado STREET AND NUMBER: —NATIONAL 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Aspen Colorado m j~i 08 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Clerk and Recorder, Courthouse COUNTY: Pitkin STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE Aspen Colorado 08 TITUE OF SURVEY: City and Townsite of Aspen DATE OF SURVEY: |~] Federal n State County Q Loca -J.A DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: County Engineer STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Aspen Colorado 08 (Check One) Excellent Q Good Q Fair Deteriorated Q Roins Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Chock One) D Altered D Unaltered Q~] Moved Q Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL ("// Jcnoivn.) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Pitkin County acquired Lots K, L, M, N, and O, Block 92 of the Original Aspen Townsite in May of 1890. -

Financial Statements

2017 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017 Pitkin County, Colorado Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Prepared by the Finance Department of Pitkin County Prepared by the Finance Department Ann Driggers, Finance Director Connie Baker, Budget Director Liz Woods, Controller Ben Ferrara, Procurement & Contracts Manager Valerie Wahlstrom, Financial Analyst Susie Atwood, Financial Analyst Gabriel Galicia, Accounts Payable Supervisor Megan Douglass, Payroll Specialist Chris Davis, Procurement Specialist Daniela Angelova, Accounts Payable Technician If you have any questions regarding this report, call or fax us at: Phone: 970-920-5220 • Fax: 970-920-5230 Our mailing address is: Pitkin County Finance Department 530 East Main Street, Suite 304 Aspen, CO 81611 Contact us through our website: www.pitkincounty.com Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Pitkin County, Colorado December 31, 2017 Table of Contents Introductory Section: Page Letter of Transmittal i ‐ v GFOA Certificate of Achievement vi Organizational Chart vii List of Principal Officers viii Financial Section: Independent Auditor’s Report A1 ‐ A3 Management’s Discussion and Analysis B1 ‐ B16 Basic Financial Statements: Government‐wide Financial Statements Statement of Net Position C1 Statement of Activities C2 Fund Financial Statements Balance Sheet ‐ Governmental Funds C3 Reconciliation of the Governmental Funds Balance Sheet to the Statement of Net Position C4 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and -

A Resolution of the Board of County Commissioners Approving the Remodel and Addition to the Courthouse Plaza Building at 530 E

AGENDA ITEM SUMMARY WORK SESSION DATE: June 13, 2016 AGENDA ITEM TITLE: A Resolution of the Board of County Commissioners approving the remodel and addition to the Courthouse Plaza Building at 530 E. Main Street, Aspen, Colorado. STAFF RESPONSIBLE: Jon Peacock, County Manager ISSUE STATEMENT: Time has been set aside at today’s meeting to consider a resolution approving the Courthouse Plaza remodel and addition, and respectfully overruling certain conditions placed on the project by the City of Aspen in Ordinance No. 10 Series of 2016. BACKGROUND: Pitkin County is an administrative arm of the State and provides essential public services. Title 30 of Colorado Revised Statutes establishes Aspen as the County Seat, and requires certain County offices to be maintained in Aspen. Since 2006 the County has identified the challenge of inadequate facilities as a barrier to providing quality and essential public services. Areas of special concern include, but are not limited to: law enforcement; the Ninth Judicial District; Elections; public hearing and meeting spaces; community planning and building services, etc. In 2006 the County engaged in two planning processes that set the stage for this project. First, in January of 2006 the County completed a comprehensive Facilities Master Plan that identified significant facility deficits for essential public services, and provided several alternatives for meeting then current and future facility needs. Alternatives included facilities located in the Aspen Core, and other options that suggested developing new facilities down valley outside of Aspen. Later in 2006 the County partnered with the City of Aspen and other non-profit entities to complete the Civic Master Plan which found in part that: “Removing civic functions from the downtown will tend to reduce the kind of community character that still makes the core of Aspen a vital and traditional downtown.” The Civic Master Plan called on the County to keep County offices in Aspen’s downtown core. -

Pitkin County Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018

Pitkin County Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018 2018 Pitkin County Hazard Mitigation Plan Pitkin County Hazard Mitigation Plan April 2, 2018 1 2018 Pitkin County Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter One: Introduction to Hazard Mitigation Planning ............................................................. 9 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................................................. 9 1.2 Participating Jurisdictions ...................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Background and Scope .......................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Mitigation Planning Requirements ...................................................................................... 10 1.5 Grant Programs Requiring Hazard Mitigation Plans............................................................ 10 1.6 Plan Organization ................................................................................................................ 11 Chapter Two: Planning Process ..................................................................................................... 13 2.1 2017 Plan Update Process ................................................................................................... 13 2.2 Multi-Jurisdictional Participation -

2012 Abstract

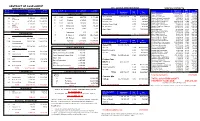

ABSTRACT OF ASSESSMENT PROPERTY CLASSIFICATION 2012 LEVIES AND REVENUES SPECIAL DISTRICTS No. of Assessed Actual No. of No. of Assessed Actual Assessed Mill Tax Parcels Valuation Valuation Parcels Acres Valuation Valuation Assessed Mill Tax District Valuation Levy Revenue Pitkin County Valuation Levy Revenue Aspen Ambulance $2,053,992,880 .204 419,015 VACANT LAND AGRICULTURE Aspen Sanitation 1,698,637,020 0.130 220,823 Commercial 180 6,960 Irrigated 905,750 3,122,900 General Fund 2,761,028,490 2.205 $6,088,068 Aspen Fire Protection 2,039,556,350 1.455 2,967,554 44 Lots 18,002,050 62,075,900 Aspen Highlands Commercial 5,099,060 34.320 175,000 Road & Bridge 0.162 447,287 Residential 165 6,410 Meadow 218,020 751,500 Aspen Highlands Residential 43,532,070 37.597 1,636,676 448 Lots 215,457,210 742,955,700 Social Services 0.065 179,467 Aspen Historic Park & Rec 2,545,246,460 0.300 763,574 209 21,442 Grazing 204,810 705,500 Aspen Valley Hospital 2,730,356,320 2.920 7,972,641 158 Vacant Lots 27,478,890 94,754,700 Healthy Comm Fund 0.707 1,952,047 Aspen Village Metropolitan 3,540,320 83.994 297,366 Minor 46 9,162 Wasteland 16,410 56,400 Basalt & Rural Fire Protection 149,801,820 8.857 1,326,795 13 Structures 231,290 797,500 TV Translator 0.259 715,107 Basalt Library 184,576,940 4.760 878,586 3 66 Forest Land 1,140 3,900 TOTAL $261,169,440 $900,583,800 Open Space 3.796 10,480,864 Basalt Sanitation 54,785,820 2.716 148,798 Basalt Water Conservancy 246,030,750 0.044 10,825 15 Possessory 620 2,100 Base Village Metro #1 3,604,940 43.500 156,815 RESIDENTIAL -

The Wheeler-Stallard House: an Interpretative History, 1888-1969

The Wheeler-Stallard House: An Interpretative History, 1888-1969 By Stacey Smith For the Aspen Historical Society Under the Auspices ofthe Roaring Fork Research Fellowship Sponsored by Ruth Whyte December, 1998 Table ofContents I. Introduction , '" 1 n. The Boom Era: 1888-1893 ,,, .. 4 Ill. The Stallard Era: 1905-1945 , 68 IV. Aspen's Rebirth: The Wheeler-Stallard House Mter 1945 95 V. Conclusion 108 Bibliography '" '" 11 0 Appendix A - Dates ofthe Wheeler-Stallard House Appendix B - Family Trees ofHouse Residents Appendix C - Photographs Appendix D- Maps and Floorplans I. Introduction For the last thirty years, the Wheeler-Stallard house has served as the headquarters ofthe Aspen Historical Society and the community's only historical museum Yet, at the same time, much ofthe history ofthe house remains obscure. The house's exact chain ofresidency, its function and appearance over time, even its architect and date ofconstruction were seemingly lost in the passage ofthe last one hundred years. This situation posed a problem when the Society began to contemplate an interior restoration ofthe house-returning the house to its original appearance and interpreting it to future visitors accurately naturally required an expansion ofthe concrete knowledge about the house. Therefore, this study is primarily aimed at filling the gaps in the Wheeler-Stallard house history and suggesting interpretative themes that may be useful in the upcoming restoration. On one level, the history ofthe Wheeler-Stallard house is a story ofindividuals. Jerome Wheeler, the silver magnate who built the house in 1888 but never lived in it, the Stallards who toiled in the house to make ends meet during the post-crash years, Walter Paepcke, the Chicago businessman who made it part ofhis skiing and cultural empire, all left indelible marks upon the house. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received &AK > :':; <.-. Inventory—Nomination Form date entered 2 0 1986 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Hotel Jerome and or common Hotel Jerome 2. Location street & number 330 E, Main St n/a not for publication city, town Aspen n/a vicinity of state Colorado code 08 county code 097 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum J£L building(s) JDL private unoccupied _JQL commercial __ park structure both XX work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object n/ a in process XX yes: restricted government scientific n/a being considered __ yes: unrestricted __ industrial __ transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name The Hotel Jerome Limii-pd street & number c /o Garfield & Hecht, 601 E. Hyman Avenue city, town Aspen n/a vicinity of state Colorado 81611 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Pitkin County Courthouse street & number 506 E. Main St. city, town Aspen state Colorado 81611 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ title Colorado Inventory of Historic Siteifes this property been determined eligible? __ yes XXno date ongoing federal XX state __ county local depository for survey records Colorado Historical Society, OAHP, 1300 Broadway___________ city, town Denver state Colorado 80203 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _^X excellent deteriorated unaltered JQL original site good ruins XX altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Hotel Jerome is located in the mountain town of Aspen and commands the community's busiest intersection. -

CLA SSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ I NAME HISTORIC Redstone Inn _____ AND/OR COMMON Redstone Inn LOCATION _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Redstone VICINITY OF 4 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE O8 P-iHc-m DQ7 CLA SSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Everett L. Irwin and Anne R. Irwin STREET & NUMBER 0082 Redstone Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Redstone/Carbondale VICINITY OF Colorado 81623 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, County Clerk and Recorder REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. pitkin County Courthouse STREETS. NUMBER 506 E. Main Street CITY. TOWN STATE Aspen Colorado 81611 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Colorado Inventory of Historic Sites (49/01/0003) DATE Ongoing —FEDERAL -XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Colorado Historical Society,. 1300 Broadway CITY. TOWN STATE Denver Colorado 80203 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE . .;.•-»•. «.. f. ,£ ,• t —EXCELLENT M '* "—DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ?_ORIGINAL SITE .XGOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Located at the southern end of the original Redstone Townsite, the Redstone Inn is a single, detached structure built in a style reminiscent of Swiss Alpine architec ture. -

(Ffmjft? STTE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR (Rev

(ffmjft? STTE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Colorado COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Pitkin INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM (Type all entries complete applicable sections) DJS 1 COMMON: Independence and Independence Mill Site AND/OR HISTOR.C: Ghipeta, Mammouth City, Mount Hope, Farwell, or S STREET AND NUMBER: Township 11 South, -Range 83 West, 6th Principal CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL Ghost Town COUNTY: Colorado Q& Pitkin 097 {iliiliiiiliiilii CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSH.P STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC ]£] District Q Building D Public Public Acquisition: n Occupied Yes: par .. Q Restricted Q Site Q Structure D Private Q In Process [31 Unoccupied "~ 38 Unrestricted D Object ffi Both [Y] Being Considered LJi — inPreservation . worki in progress ' — 1 u PRESENT USE ("Check One or More as Appropriate) [J Agricultural Jf] Government | | Park I I Transportation j~1 Comments a: Q Commercial D Industrial Q] Private Residence H] Other (Specify) JS. White n Educational d Military Q Religious River Nat'1 [~1 Entertainment CU Museum | | Scientific Forest OWNER'S NAME: ^6T j6t O « ?! fc U.S. Government and Patented Mining Claim Owners HI STREET AND NUMBER: LU CITY OR TOWN: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Pitkin County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Aspen Colorado 08 TITLE OF SURVEY: Independence Pass, Colorado? U.S.G.S. Topographical Map DATE OF SURVEY: I960 Federal State County L°« DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: U.S. Department of the Interior. Geological Survey Offing STREET AND NUMBER: Federal Office Building, 19th and Stout CITY OR TOWN: Denver Colorado Q8 (Check One) llent D Good Q Fair Q Deteriorated £§ Ruins Q Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) Altered [Xj Unaltered Moved [A| Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The ruins of Independence lie in a meadow in the valley of the Roaring Fork River at the western foot of Independence Pass. -

1. Name Historic Vehicular Bridges in Colorado (Theme Resource) And/Or Common Vehicular Bridges in Colorado 2

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Vehicular Bridges in Colorado (Theme Resource) and/or common Vehicular Bridges in Colorado 2. Location street & number multiple locations (see HAER Inventory Cards) n/ a not for publication city, town see attached forms n,/a vicinity of congressional district state Colorado code 08 county multiple code see attached 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum building(s) private x unoccupied commercial park structure x both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific x thematic being considered x yes: unrestricted industrial x transportation group x n/a no military x other': abandoned 4. Owner of Property name multiple ownership (see Addendum, Item 4) street & number city, town n/a vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. multiple locations (see Addendum, Item 4) city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ title Colorado Inventory of Historic Sites has this property been determined elegible? _x_yes no date 1984 federal JDL state county local depository for survey records Colorado Historical Society - Preservation Office city, town Denver state Colorado 7. Description Condition Check one Ch<jck one X excellent deteriorated x unaltered X original site X . good ruins X altered X _ moved date (see HAER cards) X fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Sixty- two spans are included in this thematic nomination of vehicular bridges in Colorado. -

Pre-Disaster Mitigation Plan Update Pitkin County, City of Aspen, Town of Snowmass Village, Town of Basalt

Pre-Disaster Mitigation Plan Update Pitkin County, City of Aspen, Town of Snowmass Village, Town of Basalt, Aspen Fire Protection District, Snowmass-Wildcat Fire Protection District, Basalt & Rural Fire Protection District, Carbondale & Rural Fire Protection District January 4, 2012 Pitkin County Pre-Disaster Mitigation Plan Update Participating Jurisdictions: Pitkin County City of Aspen Town of Snowmass Village Town of Basalt Aspen Fire Protection District Snowmass-Wildcat Fire Protection District Basalt & Rural Fire Protection District Carbondale & Rural Fire Protection District 04 January 2012 Emergency Management Pitkin County Sheriff's Office 506 E Main Street, Garden Level Aspen, CO 81611 Telephone: 970.920.5234 Pitkin County Pre- Disaster Mitigation Plan Disclaimer: This plan has been specifically prepared for planning purposes only. The figures and specifications contained herein are not suitable for individual property analyses or budgeting purposes. Mapping and analyses were conducted using data from others and were not technically verified for accuracy. Modeling software used for this plan is limited to planning-level analyses. ii Pitkin County Pre- Disaster Mitigation Plan Acknowledgements Pitkin County Emergency Management x Tom Grady, Pitkin County Emergency Manager x Valerie MacDonald, Pitkin Emergency Management Administrator Aspen/Pitkin County Public Safety Council x Pitkin County Board of Commissioners x Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office x Pitkin County Combined Communications x Pitkin County Airport x Aspen Ambulance