Heather and Hillforts Y Grug A’R Caerau A’R Grug Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management Plan 2014 - 2019

Management Plan 2014 - 2019 Part One STRATEGY Introduction 1 AONB Designation 3 Setting the Plan in Context 7 An Ecosystem Approach 13 What makes the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Special 19 A Vision for the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB 25 Landscape Quality & Character 27 Habitats and Wildlife 31 The Historic Environment 39 Access, Recreation and Tourism 49 Culture and People 55 Introduction The Clwydian Range and Dee lies the glorious Dee Valley Valley Area of Outstanding with historic Llangollen, a Natural Beauty is the dramatic famous market town rich in upland frontier to North cultural and industrial heritage, Wales embracing some of the including the Pontcysyllte country’s most wonderful Aqueduct and Llangollen Canal, countryside. a designated World Heritage Site. The Clwydian Range is an unmistakeable chain of 7KH2DȇV'\NH1DWLRQDO heather clad summits topped Trail traverses this specially by Britain’s most strikingly protected area, one of the least situated hillforts. Beyond the discovered yet most welcoming windswept Horseshoe Pass, and easiest to explore of over Llantysilio Mountain, %ULWDLQȇVȴQHVWODQGVFDSHV About this Plan In 2011 the Clwydian Range AONB and Dee Valley and has been $21%WRZRUNWRJHWKHUWRDFKLHYH was exteneded to include the Dee prepared by the AONB Unit in its aspirations. It will ensure Valley and part of the Vales of close collaboration with key that AONB purposes are being Llangollen. An interim statement partners and stake holders GHOLYHUHGZKLOVWFRQWULEXWLQJWR for this Southern extension including landowners and WKHDLPVDQGREMHFWLYHVRIRWKHU to the AONB was produced custodians of key features. This strategies for the area. in 2012 as an addendum to LVDȴYH\HDUSODQIRUWKHHQWLUH the 2009 Management Plan community of the AONB not just 7KLV0DQDJHPHQW3ODQLVGLHUHQW for the Clwydian Range. -

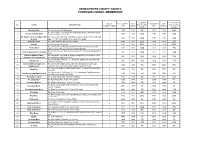

Proposed Arrangements Table

DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % variance % variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2017 ELECTORATE 2022 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from County COUNCILLORS 2017 RATIO 2022 RATIO average average 1 Bodelwyddan The Community of Bodelwyddan 1 1,635 1,635 3% 1,828 1,828 11% The Communities of Cynwyd 468 (494) and Llandrillo 497 (530) and the 2 Corwen and Llandrillo 2 2,837 1,419 -11% 2,946 1,473 -11% Town of Corwen 1,872 (1,922) Denbigh Central and Upper with The Community of Henllan 689 (752) and the Central 1,610 (1,610) and 3 3 4,017 1,339 -16% 4,157 1,386 -16% Henllan Upper 1,718 (1,795) Wards of the Town of Denbigh 4 Denbigh Lower The Lower Ward of the Town of Denbigh 2 3,606 1,803 13% 3,830 1,915 16% 5 Dyserth The Community of Dyserth 1 1,957 1,957 23% 2,149 2,149 30% The Communities of Betws Gwerfil Goch 283 (283), Clocaenog 196 6 Efenechtyd 1 1,369 1,369 -14% 1,528 1,528 -7% (196), Derwen 375 (412) and Efenechtyd 515 (637). The Communities of Llanarmonmon-yn-Ial 900 (960) and Llandegla 512 7 Llanarmon-yn-Iâl and Llandegla 1 1,412 1,412 -11% 1,472 1,472 -11% (512) Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, The Communities of Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd 669 (727), Llanferres 658 8 1 1,871 1,871 18% 1,969 1,969 19% Llanferres and Llangynhafal (677) and Llangynhafal 544 (565) The Community of Aberwheeler 269 (269), Llandyrnog 869 (944) and 9 Llandyrnog 1 1,761 1,761 11% 1,836 1,836 11% Llanynys 623 (623) Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd and The Community of Bryneglwys 307 (333), Gwyddelwern 403 (432), 10 1 1,840 1,840 16% 2,056 2,056 25% Gwyddelwern Llanelidan -

Archaeological Excavation of Moel Arthur 2017

CLWYDIAN RANGE ARCHAEOLOGY GROUP (CRAG) ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION OF MOEL ARTHUR 2017 Dr Wendy Whitby & Karen Lowery Archaeological Excavation of Moel Arthur 2017 Contents General Background p.2 Summary of Previous Excavations on Moel Arthur by Clwydian Range Archaeology Group p.5 2017 Excavation Introduction p.5 Approach to Excavation p.9 Excavation p.9 Southern End of Trench p.12 Central Area of Trench p.15 Northern End of Trench p.19 Finds Discussion p.21 Interpretation of Excavation p.26 Future Work p.27 Acknowledgements p.27 References p.29 Appendices: 1. Brooks I.P., 2014, Land Below Moel Arthur Geophysical Survey, Engineering Archaeological Services Limited, EAS Client Report 2014/10. 2. SUERC (Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre), 2016, Radiocarbon Dating Report: SUERC 66219-66221 (GU40089-40091). 3. Report on the Excavations on Moel Arthur in 2015 by Irene Milhench and Philip Culver on behalf of CRAG 4. Archaeological Services Durham University, 2015, Charcoal Identification and C14 Preparation, Report: 4015. 5. Walker, E., 2016, Analysis of the flints found on Moel Arthur 2011- 2015. Unpublished report. 6. 2017 Excavation - Context Index 7. 2017 Finds description table. 1 General Background Moel Arthur is located towards the north end of the Clwydian Hills in Denbighshire (SJ145600) and is 456m (Ordnance Survey, 2005) at its highest point. Situated on the summit of Moel Arthur is a hillfort (HER Clwyd Powys 102311; NMR SJ 16 SE) having an internal area of approximately 2 hectares (https://hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk/). This small but imposing structure occupies a strong defensive position dominating the Bwlch y Frainc pass. -

Tourism, Culture and Countryside

TOURISM, CULTURE AND COUNTRYSIDE SERVICE PLAN Key Priorities and Improvements for 2009 – 2011 Directorate : Environment Service : Tourism Culture & Countryside Head of Service: Paul Murphy Lead Member : David Thomas 1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Tourism, Culture and Countryside became part of the Environment Directorate on May 1 2008, moving across from the Lifelong Learning Directorate. The service is made up of the following :- Countryside Services – comprises an integrated team of different specialisms including: Biodiversity and Nature Conservation; Archaeology; Coed Cymru; Wardens, Countryside Recreation and Visitor Services; Heather and Hillforts; and manages the Clwydian Range Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), initiatives on Walking for Health, Open and Coastal Access, and owns and manages 2 Country Parks and a further 22 Countryside Sites. The Services’ work is wide-ranging, is both statutory and non-statutory in nature and involves partnerships with external agencies and organisations in most cases. The work of the Service within the Clwydian Range Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), Local Biodiversity Action Plan (LBAP) and Heather and Hillforts HLF project is a good example of the essential collaboration and the close co-ordination needed in our activities. The Countryside Council for Wales, as a key funding and work partner, also guide and influence our work through jointly set objectives and outcomes. Heritage Services – responsible for the management and development of the County's heritage provision including Nantclwyd y Dre, Plas Newydd, Llangollen; Rhyl Museum; Ruthin Gaol; and the Service’s museum store.Each venue has a wealth of material and is an ideal educational resource. The service also arranges exhibitions and works closely with local history and heritage organisations, and school groups. -

Andrew Farrow Chief Officer Flintshire County Council Country Hall Mold CH7 6NF

Ein cyf/Our ref: CAS-17668 Eich cyf/Your ref: 054863 Llwyn Brain, Ffordd Bangor Gwynedd LL57 2BX Ebost/Email: [email protected] Ffôn/Phone: 03000655240 Andrew Farrow Chief Officer Flintshire County Council Country Hall Mold CH7 6NF 04/05/2016 I sylw / For the attention of: Mr D G Jones Dear Sir, PROPOSAL: Change of use of disused quarry to country park incorporating heritage attraction, recreational uses and visitor centre with associated parking. LOCATION: Hanson Fagl Lane Quarry, Fagl Lane, Hope Thank you for consulting Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru / Natural Resources Wales about the above, which was received on the 8th of April 2016. Natural Resources Wales brings together the work of the Countryside Council for Wales, Environment Agency Wales and Forestry Commission Wales, as well as some functions of Welsh Government. Our purpose is to ensure that the natural resources of Wales are sustainably maintained, used and enhanced, now and in the future. We have significant concerns with the proposed development as submitted. NRW recommend that planning permission should only be given if the following requirements can be met. If these requirements are not met then we would object to this application. Summary of requirements Requirement 1- Further information on Great crested newts Requirement 2- Further information on Bats Requirement 3- Updated Flood consequence assessment Tŷ Cambria 29 Heol Casnewydd Caerdydd CF24 0TP Cambria House 29 Newport Road Cardiff CF24 0TP Croesewir gohebiaeth yn y Gymraeg a’r Saesneg Correspondence welcomed in Welsh and English Protected Species The application is supported by an ecological submission (Reference: Guest, J. -

Historic Settlements in Denbighshire

CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire THE CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire R J Silvester, C H R Martin and S E Watson March 2014 Report for Cadw The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR tel (01938) 553670, fax (01938) 552179 www.cpat.org.uk © CPAT 2014 CPAT Report no. 1257 Historic Settlements in Denbighshire, 2014 An introduction............................................................................................................................ 2 A brief overview of Denbighshire’s historic settlements ............................................................ 6 Bettws Gwerfil Goch................................................................................................................... 8 Bodfari....................................................................................................................................... 11 Bryneglwys................................................................................................................................ 14 Carrog (Llansantffraid Glyn Dyfrdwy) .................................................................................... 16 Clocaenog.................................................................................................................................. 19 Corwen ...................................................................................................................................... 22 Cwm ......................................................................................................................................... -

Flintshire LDP SA Scoping Report

Strategic Environmental Assessment and Sustainability Appraisal Local Development Plan SA Scoping Report Hyder Consulting (UK) Limited 2212959 Firecrest Court Centre Park Warrington WA1 1RG United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1925 800 700 Fax: +44 (0)1925 572 462 www.hyderconsulting.com Flintshire County Council Strategic Environmental Assessment and Sustainability Appraisal Local Development Plan SA Scoping Report Author Mwale Mutale Checker Kate Burrows Approver David Hourd Report No 001-UA006826-UE31-01 Date 18 March 2015 This report has been prepared for Flintshire County Council in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment for Local Development Plan dated 23 September 2014. Hyder Consulting (UK) Limited (2212959) cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. Strategic Environmental Assessment and Sustainability Appraisal —Local Development Plan Hyder Consulting (UK) Limited-2212959 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION TO AND PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ................ 1 1.1 Purpose of the SA Scoping Report .................................................... 1 1.2 Background to the County ................................................................. 1 1.3 Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Assessment ...... 3 1.4 Consultation ...................................................................................... 3 1.5 Habitats Regulations Assessment...................................................... 3 2 THE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN ................................................ -

Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB Annual Report 2016/17

Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB Annual Report 2016/17 Contents • Introduction Page 3 Communities and People Page 4 1. Governance 2. Community Engagement Land Management and the Natural Environment Page 9 3. Heather Moorland 4. Limestone Grassland, cliffs and Screes 5. Broad leaved woodland and Veteran Trees 6. River Valleys. The Historic Environment Page 16 7. Industrial Features and the World Heritage Site 8. Historic Defensive Features 9. Small Historic Features 10. Boundaries Access Recreation and Tourism Page 22 11. Iconic Visitor sites 12. Offas Dyke Path National Trail and Promoted Routes. Landscape and Character and the Built Environment Page 30 13. Landscape Quality and Character 14. The Built Environment. Page 2 | 33 Introduction The Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is the dramatic upland frontier of North East Wales. This AONB almost touches the coast at Prestatyn Hillside in the north and stretches south as far Moel Fferna, the highest point in the AONB at 630 metres, it covers 390 square kilometres of windswept hilltops, heather moorland, limestone crags and wooded valleys. The Clwydian Range is an unmistakeable chain of purple heather-clad summits, topped by Britain’s most strikingly situated Hillforts. The Range’s highest hill at 554 metres is Moel Famau, a familiar site to residents of the North West. The historic Jubilee Tower surmounts this hill with views over 11 counties. Beyond the windswept Horseshoe Pass, over Llantysilio Mountain, lies the glorious Dee Valley with historic Llangollen, a famous market town rich in cultural and industrial heritage. The AONB is led by the Joint Committee (JC), the Committee consists of two Executive Members from each of the three local authorities that the AONB straddles. -

Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy

Environment Directorate Contaminated Land Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy Revision 4 | February 2013 Foreward This Contaminated Land Strategy describes how Flintshire County Council is required to identify sites within its administrative control that may be affected by land contamination. The document also explains the statutory guidance, legislative provisions, processes and procedures that the Council will follow in order to investigate those sites, to identify statutorily Contaminated Land where necessary and to remediate Contaminated Land. The Council first published its Contaminated Land Strategy in September 2002. Since then a number of investigations to assess land contamination have been carried out and significant changes to legislation and guidance documents have taken place. This revision of the Strategy has taken these changes into account and amendments have been made where necessary. This revision of the Strategy replaces all previous revisions of Flintshire County Council’s Contaminated Land Strategy. Flintshire County Council Environment Directorate Public Protection Pollution Control Section Phase 4 County Hall Mold Flintshire CH7 6NH Contaminated Land Strategy Revision 4 February 20 Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy 2 Executive Summary Land can be affected by contamination in the environment as a result of human activity and as a result of natural processes. The presence of contamination may cause harm or present risks to health, animals, buildings or the environment. However, just because contamination is present does not mean that the land is Contaminated Land or that there is a problem. On 1st July 2001, legislation requiring land contamination to be investigated and addressed was enacted in Wales. The legislation is known as Part IIa of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 and it introduced a detailed way by which land contamination could be regulated. -

FOLK-LORE and FOLK-STORIES of WALES the HISTORY of PEMBROKESHIRE by the Rev

i G-R so I FOLK-LORE AND FOLK-STORIES OF WALES THE HISTORY OF PEMBROKESHIRE By the Rev. JAMES PHILLIPS Demy 8vo», Cloth Gilt, Z2l6 net {by post i2(ii), Pembrokeshire, compared with some of the counties of Wales, has been fortunate in having a very considerable published literature, but as yet no history in moderate compass at a popular price has been issued. The present work will supply the need that has long been felt. WEST IRISH FOLK- TALES S> ROMANCES COLLECTED AND TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION By WILLIAM LARMINIE Crown 8vo., Roxburgh Gilt, lojC net (by post 10(1j). Cloth Gilt,3l6 net {by posi 3lio% In this work the tales were all written down in Irish, word for word, from the dictation of the narrators, whose name^ and localities are in every case given. The translation is closely literal. It is hoped' it will satisfy the most rigid requirements of the scientific Folk-lorist. INDIAN FOLK-TALES BEING SIDELIGHTS ON VILLAGE LIFE IN BILASPORE, CENTRAL PROVINCES By E. M. GORDON Second Edition, rez'ised. Cloth, 1/6 net (by post 1/9). " The Literary World says : A valuable contribution to Indian folk-lore. The volume is full of folk-lore and quaint and curious knowledge, and there is not a superfluous word in it." THE ANTIQUARY AN ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE STUDY OF THE PAST Edited by G. L. APPERSON, I.S.O. Price 6d, Monthly. 6/- per annum postfree, specimen copy sent post free, td. London : Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C. FOLK-LORE AND FOLK- STORIES OF WALES BY MARIE TREVELYAN Author of "Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character," " From Snowdon to the Sea," " The Land of Arthur," *' Britain's Greatness Foretold," &c. -

Other Wildlife Sites in Denbighshire

Welcome Making sense of the jargon Some sites have local, national or international designations. This means that the sites have to be managed and preserved in a special way to safeguard the animals, habitats, archaeology or landscapes that are rare or in danger. LNR - Local Nature Reserve SSSI - Site of Special Scientific Interest SAC - Special Area of Conservation AONB - Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty SAM - Scheduled Ancient Monument WS - County Wildlife Sites These symbols show what facilities are available on the sites: This leaflet is designed to show you the Café or restaurant nearby room for hire managed countryside sites in the area, how shop events to get to them, what you can do when you picnic tables hang/para gliding get there and why they are such valuable toilets & model flying places to visit and protect. The centre map disabled facilities historic remains shows the location of the sites; please refer to (parking, toilets, view) the map reference to help you to your leaflet cycling route destination. Information panels bridlepath ()limited coach parking parking on site 1 We hope you enjoy exploring these beautiful public bus route parking within /2 mile countryside sites. schools resources views Sites are graded according to how accessible the main paths are, please look for these symbols: Whilst every effort has been made to make this booklet as 1 accurate as possible, - Most paths are flat with hard surface. neither authors nor 2 publishers accept any - Some gradients and hard surfaces. responsibility for the 3 consequence of any - Gradients with surfaces of loose stones and grass. -

Clwydian Range and Dee Valley State Of

Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty State of the AONB Report 2014 – 2019 In setting an agenda that will ensure the special qualities and features of the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley are preserved, it is first necessary to make an assessment of their current extent and condition. It is also important that the issues impacting upon them are identified and that factors likely to impact upon them in the future are anticipated. The State of the AONB Report identifies where possible the extent and condition of each feature and the factors impacting on them. It also seeks to identify an ideal state for these features and begins to establish indicators that will help to define what we are aiming for in pursuing the good health of the AONB. It is an on‐going process that relies on constant data gathering and monitoring and should be able to respond to changing demands on the environment. There is a requirement for up to date information that will lead to informed responses to environmental change. Tranquillity, Remoteness and Wilderness Tranquillity, Remoteness Intrusion Light from the major Further intrusion mapping required and settlements, particularly to the Wilderness A variety of factors can have an east and north of the AONB, Extent: impact on the Tranquillity, have a significant impact on Illuminated bollards and signs within Remoteness and Wilderness of dark night skies. Denbighshire – 80 within AONB the AONB. Traffic noise, light Light and noise pollution from Wrexham - unknown pollution, the impact of transport, development and Flintshire - unknown quarrying and utility recreation erodes tranquillity – Street lights installations can all have an A55, A494, A5, A542 1,350 directly adjacent to or within effect on the tranquillity of the Intrusive and degrading AONB in Denbighshire.