Reevaluating the Carnegie Survey: New Uses for Frances Benjamin Johnston's Pictorial Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MT VERNON SQUARE Fairfax County

Richmond Highway (Route 1) & Arlington Drive Alexandria, VA 22306 MT VERNON SQUARE Fairfax County SITE MT. VERNON SQUARE ( 5 2 0 3 1 ,00 8 A D T 0 ) RETAIL FOR SUBLEASE JOIN: • Size: 57,816 SF (divisible). • Term: Through 4/30/2026 with 8, five-year options to renew. • Uses Considered: ALL uses considered including grocery. • Mt. Vernon Square is located on heavily traveled Richmond Highway (Route 1) with over 53,000 vehicles per day. ( 5 2 • This property has0 3 a total of 70,617 SF of retail that includes: M&T Bank, Ledo Pizza, and Cricket Wireless. 1 ,00 8 A MT. VERNON D T 0 PLAZA ) Jake Levin 8065 Leesburg Pike, Suite 700 [email protected] Tysons, VA 22182 202-909-6102 klnb.com Richmond Hwy Richmond 6/11/2019 PROPERTY CAPSULE: Retail + Commercial Real Estate iPad Leasing App, Automated Marketing Flyers, Site Plans, & More 1 Mile 3 Miles 5 Miles 19,273 115,720 280,132 Richmond Highway (Route 1) & Arlington6,689 Drive43,290 Alexandria,115,935 VA 22306 $57,205 $93,128 $103,083 MT VERNON SQUARE Fairfax County DEMOGRAPHICS | 2018: 1-MILE 3-MILE 5-MILE Population 19,273 115,720 280,132 Daytime Population 15,868 81,238 269,157 Households 6,689 43,290 15,935 Average HH Income SITE $84,518 $127,286 $137,003 CLICK TO DOWNLOAD DEMOGRAPHIC REPORT 1 MILE TRAFFIC COUNTS | 2019: Richmond Hwy (Route 1) Arlington Dr. 53,000 ADT 3 MILE 5 MILE LOCATION & DEMOGRAPHICS Jake Levin 8065 Leesburg Pike, Suite 700 [email protected] Tysons, VA 22182 202-909-6102 klnb.com https://maps.propertycapsule.com/map/print 1/2 Richmond Highway (Route 1) & Arlington Drive -

Temple Pedigrees

SOME TEMPLE PEDIGREES. A GENEALOGY OF THE KNOWN DESCENDANTS OF ABRAHAM TEMPLE, SALEM. MASS., 1-N 1636. TO WHICH IS ADDED GE.",EALOGIES OF TDlPLE FA)lILIES SETI'LING IN READING, MASS., CHESTER CO., PA., AYLF.TTS, VA., GALWAY, N. Y., AND ELSEWHERE. ALSO BRIEF GE.-.:EALOGIES OF FAMILIES CONNECTED BY MARRIAGE WITH THE FOREGOING. VIZ: EAM'.ES, CASE. WELCH, KELLUM. CA)fPBELL. WILSON, HIATT, SPRAY. COOK, TREDWAY AND MURDOCK. BY LEVI DAJ."ITEL TEMPLE. BOSTON: PRCNTED BY DA-VID CLAPP & SON. l 9 0 0. TO MY CHJLDRE.....;, cli:cnctifft Ei}ahctb anb ~tuman ~cllum i!i:cmplc, Wrr11 nu,: Hol'E THAT TUEY WlLL PROVE WORTHY 1:.HERl'l'OI\S 01' A.~ HOliORAIILF. LJ:;EAcF. A."1> ADD FRESH LUSTRE 'fO A D1s,l:;GUISH£D NAME, I Dl!:DlCATE THIS VOLUME. Uo tbe ~urcbaser. You may wish at some time to sell this volume. Should ·such be the case in one week, or twenty years, if you will write me the condition of the book and your lowest cash price, post-paid, I will endeavor to find a buyer for it. With every good wish, Your friend, LEVI D. TEMPLE. I'LKMl:SGTOS. X. J. LEVI DANIEL TEMPLE. CONTENTS. I:sTROt>t:CT10:s-TnE TEltPLE F A.,nLY 5-8 DESCEXTlA:STS 01-' ARRAHAlt TEltPLE 9-203 BAKER F.\lt!LY 66 EAln:s F.um. Y 66-67 C:..sv. F:..,nr., 114-116 TREDW.\Y FAllll.Y 133-135 ,vEr.cn FAl!Il.Y • lil-174 KELLt:lt F:..mr. Y 192-194 HIATT F,\ltlLY 195-196 W1r.so:s F.uur.Y 196-198 CooK F.unLY 197 CAltPBELL F.\)IILY 198-200 SPRAY F.nnLY 200-202 DESCI-::SllAXTS OF SAltuEL l\It:nt>OCK 204-211 DESCEXTlAXTS OF ROBERT TEltPLE 212-260 D1-:scE:st>A:sTs 01-· Wn.LIAlt TEltPLE OF CooltBS LA:SE 261-279 DESCE:SDA:STS OF W1LT.IAlt TEllPLE OF TITRING OF WICK 280-289 D1-:sc1-:XDA:STS 01-' Au:xAXDER TEl[PLE • 290-293 DESCF.XDAXTS OF ICHABOD ,\..'m JoHX TEltPLE 294-297 OTHER TEltPLE F AlUr.IES 298 ADDEXDA 293,297 E."tTRACTS FR0lt E:SGLISB WILLS 299-301 INDEX 302-316 THE TEMPLE FAMILY. -

Corridor Analysis for the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia

Corridor Analysis For The Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail In Northern Virginia June 2011 Acknowledgements The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this report: Don Briggs, Superintendent of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail for the National Park Service; Liz Cronauer, Fairfax County Park Authority; Mike DePue, Prince William Park Authority; Bill Ference, City of Leesburg Park Director; Yon Lambert, City of Alexandria Department of Transportation; Ursula Lemanski, Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program for the National Park Service; Mark Novak, Loudoun County Park Authority; Patti Pakkala, Prince William County Park Authority; Kate Rudacille, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; Jennifer Wampler, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation; and Greg Weiler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The report is an NVRC staff product, supported with funds provided through a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Region National Park Service. Any assessments, conclusions, or recommendations contained in this report represent the results of the NVRC staff’s technical investigation and do not represent policy positions of the Northern Virginia Regional Commission unless so stated in an adopted resolution of said Commission. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the jurisdictions, the National Park Service, or any of its sub agencies. Funding for this report was through a cooperative agreement with The National Park Service Report prepared by: Debbie Spiliotopoulos, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission with assistance from Samantha Kinzer, Environmental Planner The Northern Virginia Regional Commission 3060 Williams Drive, Suite 510 Fairfax, VA 22031 703.642.0700 www.novaregion.org Page 2 Northern Virginia Regional Commission As of May 2011 Chairman Hon. -

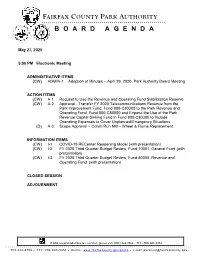

Fairfax County Park Authority Board Agenda

FAIRFAX COUNTY PARK AUTHORITY BOARD AGENDA May 27, 2020 5:00 PM Electronic Meeting ADMINISTRATIVE ITEMS (CW) ADMIN-1 Adoption of Minutes – April 29, 2020, Park Authority Board Meeting ACTION ITEMS (CW) A-1 Request to Use the Revenue and Operating Fund Stabilization Reserve (CW) A-2 Approval - Transfer FY 2020 Telecommunications Revenue from the Park Improvement Fund, Fund 800-C80300 to the Park Revenue and Operating Fund, Fund 800-C80000 and Expand the Use of the Park Revenue Capital Sinking Fund in Fund 800-C80300 to Include Operating Expenses to Cover Unplanned/Emergency Situations (D) A-3 Scope Approval – Colvin Run Mill – Wheel & Flume Replacement INFORMATION ITEMS (CW) I-1 COVID-19 RECenter Reopening Model (with presentation) (CW) I-2 FY 2020 Third Quarter Budget Review, Fund 10001, General Fund (with presentation) (CW) I-3 FY 2020 Third Quarter Budget Review, Fund 80000, Revenue and Operating Fund (with presentation) CLOSED SESSION ADJOURNMENT If ADA accommodations are needed, please call (703) 324-8563. TTY (703) 803-3354 703-324-8700 TTY: 703-803-3354 Online: www.fairfaxcounty.gov/parks e-mail:[email protected] Board Agenda Item May 27, 2020 ADMINISTRATIVE – 1 Adoption of Minutes – April 29, 2020, Park Authority Board Meeting ISSUE: Adoption of the minutes of the April 29, 2020, Park Authority Board meeting. RECOMMENDATION: The Park Authority Executive Director recommends adoption of the minutes of the April 29, 2020, Park Authority Board meeting. TIMING: Board action is requested on May 27, 2020. FISCAL IMPACT: None ENCLOSED DOCUMENTS: Attachment 1: Minutes of the April 29, 2020, Park Authority Board Meeting STAFF: Kirk W. -

Mount Vernon Woods Park Master Plan Revision

MOUNT VERNON WOODS PARK MASTER PLAN REVISION MOUNT VERNON WOODS PARK Master Plan Revision December 16, 2015 Fairfax County Park Authority Page MOUNT VERNON WOODS PARK MASTER PLAN REVISION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FAIRFAX COUNTY PARK AUTHORITY BOARD William G. Bouie, Chairman, Hunter Mill District Ken Quincy, Vice Chairman, Providence District Harold L. Strickland, Treasurer, Sully District Walter Alcorn, At-Large Member Edward R. Batten, Sr., Lee District Mary Cortina, At-Large Member Linwood Gorham, Mount Vernon District Faisal Khan, At-Large Member Michael Thompson, Jr., Springfield District Frank S. Vajda, Mason District Anthony J. Vellucci, Braddock District Grace Han Wolf, Dranesville District SENIOR STAFF Kirk W. Kincannon, CPRP, Director Sara Baldwin, Deputy Director/Chief Operating Officer Aimee Long Vosper, Deputy Director/Chief of Business Development David Bowden, Director, Planning & Development Division Barbara Nugent, Director, Park Services Division Cindy Walsh, Director, Resource Management Division Todd Johnson, Director, Park Operations Division Judith Pedersen, Public Information Officer PROJECT TEAM Andrea Dorlester, AICP, Project Manager, Park Planning Branch, PDD Sandy Stallman, AICP, Manager, Park Planning Branch, PDD Andy Galusha, Park Planner, Park Planning Branch, PDD Philip Hager, Area 3 Manager, POD Karen Lindquist, Historic Preservation Program Coordinator, RMD Kristin Sinclair, Natural Resource Specialist, RMD Lloyd Tucker, Region 1 Manager, Department of Neighborhood and Community Services Samantha Wangsgard, Urban -

The Macgill--Mcgill Family of Maryland

SEP i ma The MaCgÍll - McGill Family of Maryland A Genealogical Record of over 400 years Beginning 1537, ending 1948 GENEALOGICAL SOCIETÏ OP THE CHURCH OF JlSUS CMOlSI OP UT7Sfc.DAY SAMS DATE MICROFILMED ITEM PROJECT and G. S. Compiled ROLL # CALL # by John McGill 1523 22nd St., N. W Washington, D. C. Copyright 1948 by John McGill Macgill Coat-of-Arms Arms, Gules, three martlets, argent. Crest, a phoenix in flames, proper. Supporters, dexter (right) a horse at liberty, argent, gorged with a collar with a chain thereto affixed, maned and hoofed or, sinister (left) a bull sable, collared and chained as the former. Motto: Sine Fine (meaning without end). Meaning of colors and symbols Gules (red) signifies Military Fortitude and Magnanimity. Argent (silver) signifies Peace and Sincerety. Or (gold) signifies Generosity and Elevation of Mind. Sable (black) signifies Constancy. Proper (proper color of object mentioned). The martlet or swallow is a favorite device in European heraldry, and has assumed a somewhat unreal character from the circumstance that it catches its food on the wing and never appears to light on the ground as other birds do. It is depicted in armory always with wings close and in pro file, with no visable legs or feet. The martlet is the appropriate "differ ence" or mark of cadency for the fourth son. It is modernly used to signify, as the bird seldom lights on land, so younger brothers have little land to rest on but the wings of their own endeavor, who, like the swallows, become the travellers in their season. -

Huntley Photo Essay and Two 6Tonez in the Wing6 on Each Ide

The mamion home a o6 ()nick comtnuction. The home cows otiginatty "H" haped, with thnee 6toniez in the middee 6ection, Huntley Photo Essay and two 6tonez in the wing6 on each ide. The Hunttey e6tate wm butt by 7hooson Fnancx4 Ma-60n. It i4 notknownwhetheA Mason tived in Hunttey. The home a a notabte ex- ampte o( eatty nineteenth centany anchitectune and tetativety a comp-Pete comptex. The Hunttey comptex comatz 04: 1. The man-Lon home 2. Nece64any and Stotage toom 3. Root cettat 4. Ice home 5. Spninghome 6. Tenant home Hunttey a an impontant anchitectutat tandmatk which now betong6 to the Hiztotic Society. The Ha-tonic Society witt begin te6toning the e6tate to pnesenve natunat took (tom the 1900'6. Hunttey 6houtd be open to the pubtic in the Fatt o( 1980. Hunttey, viewed (tom the teat. The Tenant hou6e iz a bnick two-4tony 6tnactute. It a appnox- imatay two hundned eventy zieet we-t o( the mamion home. It Hun-e.g, manoion hou6e viewed (tom the (ton-t. banned in 1947; now onty the extetion watt'is otiginat. 38 39 The wanehome i4 bkick, and the 0Aing dikectty acko66 the istkeet, 601En1 the 6oukce o4 the south bkanch o4 Uttle Hunting Ckeeh. Now ovengkown, it i4 diVlicutt GENERATIONS to detekmine miginat. Thete Ls no goW o6 wate olt it'is The :)tkuctuke 414 att undengitound, atmcpst comptetety 6iteed. Miller Changes in the Groveton community can be witnessed through de- velopment and modification, but one thing that rarely changes is the people. The contrast between the usual suburban community with its short-term residencies and the Groveton cammunity is the combination the Groveton area has of short-term families and families that have lived here for as long as four generations. -

Copper Retirement ID No. 2019-01-A-VA

6929 N. Lakewood Avenue Tulsa, OK 74117 PUBLIC NOTICE OF COPPER RETIREMENT UNDER RULE 51.333 Copper Retirement ID No. 2019-01-A-VA March 20, 2019 Carrier: Verizon Virginia LLC, 22001 Loudon County Parkway, Ashburn, VA 20147 Contact: For additional information on these planned network changes, please contact: Janet Gazlay Martin Director – Network Transformation Verizon Communications 230 W. 36th Street, Room 802 New York, NY 10018 1-844-881-4693 Implementation Date: On or after March 27, 2020 Planned Network Change(s) will occur at specified locations in the following wire center in Virginia. Exhibit A provides the list of addresses associated with the following wire center. Wire Center Address CLLI ANNANDALE 6538 Little River Tpke., Alexandria, VA 22370 ALXNVAAD ALEXANDRIA 1316 Mt. Vernon Ave., Alexandria, VA 22370 ALXNVAAX BARCROFT 4805 King St., Alexandria, VA 22206 ALXNVABA BURGUNDY ROAD 3101 Burgundy Rd., Alexandria, VA 22303 ALXNVABR MOUNT VERNON 8534 Old Mt. Vernon Rd., Alexandria, VA 22309 ALXNVAMV ARLINGTON 1025 N. Irving St., Arlington, VA 22201 ARTNVAAR CRYSTAL CITY 400 S. 11th St., Arlington, VA 22202 ARTNVACY BETHIA 13511 Hull Street Rd., Bethia, VA 23112 BTHIVABT CHESTER 3807 W. Hundred Rd., Chester, VA 23831 CHESVACR CHANCELLOR 1 11940 Cherry Rd., Chancellor, VA 22407 CHNCVAXA CHANCELLOR 2 Rte 673 & Rte 628, Chancellor, VA 22401 CHNCVAXB 957 N. George Washington Hwy., Chesapeake, DEEP CREEK CHSKVADC VA 23323 CULPEPER 502 E. Piedmont St., Culpeper, VA 22701 CLPPVACU CRITTENDEN 409 Battlefield Blvd., Great Bridge, VA 23320 CRTDVAXA DALE CITY 14701 Cloverdale Rd., Dale City, VA 22193 DLCYVAXA Wire Center Address CLLI LEE HILL 4633 Mine Rd., Fredericksburg, VA 22408 FRBGVALH FAIRFAX 10431 Fairfax Blvd., Fairfax, VA 22030 FRFXVAFF BATTLEFIELD 765 Battlefield Blvd., Great Bridge, VA 23320 GRBRVAXB GREAT FALLS 755 Walker Rd., Great Falls, VA 22066 GRFLVAGF GROVETON 2806 Popkins Ln., Groveton, VA 22306 GVTNVAGR DRUMMONDS CORNER 11 Wythe Creek Rd., Hampton, VA 23666 HMPNVADC QUEEN STREET 131 E. -

Nomination Form

(Rev. 10-90) NPS Form 10-900 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the infonnation requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Temple Hall other names/site mrmber Temple Hall Farm Regional Park; VDHR File No. 053-0303 2. Location street & number 15764 Temple Hall Lane not for publication NIA city or town____________________________ vicinity_...;;X;..;;.... ___ state Virginia code VA county__ L_ou_d_o_un ____ code 107 Zip _2_0_1_7_6 ______ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property b considered significant_ nationally_ statewide _x_ locally. -

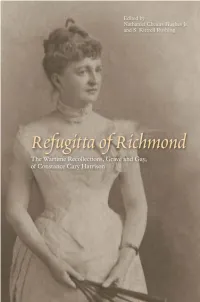

The Wartime Recollections, Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / Edited, Annotated, and with an Introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr

Refugitta of Richmond RefugittaThe Wartime Recollections, of Richmond Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison Edited by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing The University of Tennessee Press • Knoxville a Copyright © 2011 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. Originally published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. Refugitta of Richmond: the wartime recollections, grave and gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / edited, annotated, and with an introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing. — 1st ed. p. cm. Originally published under title: Recollections grave and gay. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN-13: 978-1-57233-792-3 eISBN-10: 1-57233-792-3 1. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. 2. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 4. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 5. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 6. Richmond (Va.)—History—Civil War, 1861–1865. I. Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs. II. Rushing, S. Kittrell. III. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843-1920 Recollections grave and gay. IV. Title. E487.H312 2011 973.7'82—dc22 20100300 Contents Preface ............................................. ix Acknowledgments .....................................xiii -

In Season at PDS

PlantherWear Each year the Alumni Board awards a tuition grant to an Upper School Financial aid recipi ent who has demonstrated leadership and Adult/Kids Panther enthusiasm. All profits from Panther Wear Sweatshirts sales support the Alumni Scholarship Fund. Color: Light grey Adult 100% cotton, Show your support!!! Kids 50/50. A dult Sizes: M, L, XL $40 Kids’ sizes: S, M, L Adult/Kids $24 Panther Fleeces Color: Navy with embroidered black panther. A dult full zip Sizes: M, L, XL Panther Caps $65 Color: Khaki with Kids 1/4 zip. embroidered black Sizes: S, M, L panther. One size. $50 $18 PDS PantherT-Shirt Color: White with royal and black panthers. A dult sizes: M, L, X L PDS Panther $18 The panthers are back! Kids’ sizes: XS, S, M, L Large, soft and cuddly, $18 with baby blue eyes. $40 Adult Panther Fleece Vest Color: Navy with embroidered black panther. Sizes: M, L, XL $50 ORDERED BY ITEM SIZE QUANTITY PRICE nam e address city state/zip daytime phone subtotal: class add 6% NJ sales tax on panther shipping? Oyes O no (add $8.00 to total for shipping costs) TOTAL: You will be notified when your items are available fo r pick-up at the PDS Development Office, Colross. Please make checks payable to Princeton Day School. Return order form with check to PDS Alumni Office, PO Box 75, The Great Road, Princeton, NJ 08542. Please call I-877-924-ALUM with any questions. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Daniel J. Graziano, Jr., Chairman PRINCETON DAY SCHOOL JOURNAL Deborah Sze Modzelewski, Vice Chair Richard W. -

Bulletin of the State Normal School, Fredericksburg, Virginia, October

Vol. I OCTOBER, 1915 No. 3 BULLETIN OF THE State Normal Scnool Fredericksburg, Virginia The Rappahannock Rn)er Country By A. B. CHANDLER, Jr., M. A., Dean of Fredericksburg Normal School Published Annually in January, April, June and October Entered as second-class matter April 12, 1915, at the Post Office at Fredericksburg, Va., under the Act of August 24, 1912 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/bulletinofstaten13univ The Rappahannock River Country) By A. B. CHANDLER, Jr., M. A. Dean Fredericksburg Normal School No attempt is made to make a complete or logically arranged survey of the Rappahannock River country, because the limits of this paper and the writer's time do not permit it. Attention is called, however, to a few of the present day characteristics of this section of the State, its industries, and its people, and stress is laid upon certain features of its more ancient life which should prove of great interest to all Virginians. Considerable space is given also to the recital of strange experiences and customs that belong to an age long since past in Virginia, and in pointed contrast to the customs and ideals of to-day; and an insight is given into the life and services of certain great Virginians who lived within this area and whose life-work, it seems to me, has hitherto received an emphasis not at all commensurate with their services to the State and the Nation. The Rappahannock River country, embracing all of the counties from Fredericksburg to the mouth of this river, is beyond doubt one of the most beautiful, fertile and picturesque sections of Virginia.