Conceptual and Strategic Approach to Implement Family Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 25, 2020

View the AOMA Dispatch on the AOMA Website here. INSIDE THIS ISSUE Register to Vote AAOA Fun Run Breast Cancer Awareness Fall Seminar Roll Up Your Sleeve CMS Pilot OMED 2020 Sandra Day O’Connor Civics AOMA Calendar Celebration Day Voter Registration Deadline is October 5th The General Election is just 38 days away. Are you registered? New to Arizona? Moved or want to change your registration? The deadline to register is October 5th. Visit https://servicearizona.com/VoterRegistration today! AOMA 40th Annual Fall Seminar: Virtual Streaming - Three Types of Credit Offered Come Together and Dig On! at the AOMA 40th Annual Fall Seminar - Virtual Streaming. Join us November 6-8, 2020 from the comfort of your home or office. Registration includes on demand access to the recorded lectures after the live event. The Arizona Osteopathic Medical Association (AOMA) is accredited by the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) to provide osteopathic continuing medical education for physicians. The AOMA designates this program for a maximum of 20 hours of AOA Category 1-A CME credits 1 of 6 9/25/2020, 1:19 PM and will report CME credits commensurate with the extent of the physician’s participation in this activity. This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Acccreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). The Arizona Osteopathic Medical Association is accredited by ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. AOMA designates this live activity for a maximum of 20 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. -

Loxley House Family Practice

HOUSE CALLS INTERPRETER SERVICES /131 450 House calls are provided for housebound patients. If If you or a family member require an interpreter possible, please ring before 11.00am to speak with your service, we can organise this for you. Please let us know doctor to organise a suitable time. For safety reasons you when you make the appointment. must be a regular patient of the practice for at least a 12 month period to qualify for house visits. If you require a WHEELCHAIR ACCESS home visit after surgery hours please call Bathurst After Access is available through our back entrance. You can Hours Medical Service 6333 2888. If it is an emergency enter via the driveway in Seymour Street. Disabled please phone 000 for an ambulance or present to the parking is also available. If you require assistance, phone Bathurst Base Hospital. 6331 7077 and the reception staff will assist you. NURSING HOME VISITS MEDICAL STUDENTS The Doctors at Loxley House Family Practice visit their As part of our commitment to medical education, Loxley Nursing Home patients regularly at a time determined by House Family Practice will occasionally have students the Doctor and/or after consultation with nursing staff at sitting in with your Doctor as observers. However please LOXLEY HOUSE FAMILY the relevant Nursing Home. feel free to request that the student leave the room at the time of your consultation. PRACTICE RESULTS PATIENT FEEDBACK We are a family medical practice committed to providing a comprehensive medical service to you and your family. Please phone after 9.00am to discuss results with your From time to time we ask our patients if they would doctor. -

Class of 2020

HARVARD LAW SCHOOL CLASS OF 2020 CLINICAL AND PRO BONO PROGRAMS LEARNING THE LAW, SERVING THE WORLD COMMENCEMENT NEWSLETTER MAY 2020 LEARNING THE LAW SERVING THE WORLD “One of the best aspects of Harvard Law School is working with the remarkable energy, creativity, and dynamism of our students. They come to HLS with a wide range of backgrounds and a wealth of experiences from which our Clinics and our clients benefit and grow. Our Clinical Program is never static—we are constantly reinventing ourselves in response to client needs, student interests, and national and international issues. As we advise and mentor individual students on their path to becoming ethical lawyers, the students, in turn, teach us to look at legal problems with a fresh set of eyes each and every day. This constant sense of wonder permeates our Clinical Programs and invigorates the learning process.” Lisa Dealy Assistant Dean for Clinical and Pro Bono Programs 1 CLASS OF 2020: BY THE NUMBERS IN-HOUSE CLINICS • Animal Law and Policy Clinic • Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation • Food Law and Policy Clinic 72% 52% • Health Law and Policy Clinic OF THE J.D. CLASS DID TWO OR PARTICIPATED IN MORE CLINICS • Criminal Justice Institute CLINICAL WORK • Crimmigration Clinic • Cyberlaw Clinic • Education Law Clinic • Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic • Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program • Harvard Legal Aid Bureau 364,637 640 AVERAGE # OF PRO • Harvard Dispute Systems Design PRO BONO HOURS Clinic COMPLETED BY THE BONO HOURS • Impact Defense Initiative J.D. CLASS OF 2020 PER STUDENT • International Human Rights Clinic • Making Rights Real: The Ghana Project Clinic • Transactional Law Clinics • WilmerHale Legal Services Center • Domestic Violence and Family 50 1035 Law Clinic PRO BONO HOURS CLINICAL • Federal Tax Clinic REQUIRED OF J.D. -

Resident Handbook Mercy Redding Family Practice Residency Program 2017-2018

Resident Handbook Mercy Redding Family Practice Residency Program 2017-2018 1 Resident Handbook Mercy Redding Family Practice Residency Program 2017-2018 I. WELCOME ................................................................................................................. 7 RESIDENCY MISSION ............................................................................................................................................. 7 OUR PARTNERSHIP IN LEARNING ..................................................................................................................... 8 INSTITUTION MISSION STATEMENT, VISION, CORE VALUES .................................................................. 9 STATEMENT OF COMMITMENT TO RESIDENCY PROGRAM .................................................................... 9 CURRICULUM ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 CURRICULUM RESOURCES ................................................................................................................................ 13 II. CLINICAL ROTATIONS AND EXPERIENCES ........................................................ 13 ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT TRAINING (PGY1, PGY2, PGY3)..................................................................... 13 BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE (PGY1, PGY2, PGY3) ................................................................................................ 14 CARDIOLOGY (PGY1, PGY2, PGY3) ................................................................................................................. -

Have You Really Addressed Your Patient's Concerns?

Ronald M. Epstein, MD, Larry Mauksch, MEd, Jennifer Carroll, MD, MPH, and Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD Have You Really Addressed Your Patient’s Concerns? These simple strategies will help you structure the medical encounter to ensure that you and your patient are on the same page. s family physicians, we often strive to provide patient-centered care and place great value on commu- nicating effectively with patients. WeA get to know our patients, their families and their concerns over time, and very often patients appreciate the care they receive. Despite our efforts, however, between 30 percent and 80 percent of patients’ expectations are not met in routine primary care visits.1 Often, important concerns remain unaddressed because the physician is not aware of the patient’s worries. Listening to audio recordings of patient- physician visits provides some insight into physician behaviors that keep patients from disclosing their concerns. For example, physicians often redirect patients at the beginning of the visit, giving patients less than 30 seconds to express their concerns.2 Later in the visit, physicians tend not to involve patients in decision making3 and, in general, rarely express empathy.4 Patients Downloaded from the Family Practice Management Web site at www.aafp.org/fpm. Copyright© 2008 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncommercial TRACY WALKER use of one individual user of the Web site. All other rights reserved. Contact [email protected] for copyright questions and/or permission requests. forget more than half of physicians’ clinical recommenda- improved patient trust and satisfaction,6 more appropri- tions,5 and differences in agendas and expectations often ate prescribing7 and more efficient practice.8 are not reconciled. -

PHYSICIANS REGISTERED in LEERS (AS of 10/30/2018) Sorted by Last Name

PHYSICIANS REGISTERED IN LEERS (AS OF 10/30/2018) Sorted by Last Name Last Name First Name Facilities (Primary - May not be all inclusive - Physician may have additional facilities) Aachi Venkat Louisiana State University Health Science Center - DM; Aaron Rachel St. Elizabeth Physicians; Ababneh Bashar LSU Interim Public Hospital - DM; Abad Jade University Health - Shreveport DM; Abadco Dustin Ochsner Foundation Hospital - DM; Abana Olaedo University Health - Shreveport DM; Abbas Syed Louisiana State University Health Science Center - DM; Abben Richard Terrebonne General Medical Center; Cardiovascular Institute of the South - Houma; Abboud Steven University Health - Shreveport DM; Abdallah Mohktar Baton Rouge General Medical Center - Bluebonnet DM; Baton Rouge General Medical Center - Mid City DM; Abdallah Amireh University Health - Shreveport DM; Abdehou Sam University Health - Shreveport DM; Abdelmalik Michael University Health - Shreveport DM; Abdo Abir Lafon Nursing Facility of the Holy Family - DM; Abedehou David Willis-Knighton Hospital - Pierremont DM; Abeer Albar Ochsner Foundation Hospital - DM; Abi Rafeh Nidal Tulane University Medical Center - DM; LSU Interim Public Hospital - DM; Abi Samra Freddy Ochsner Foundation Hospital - DM; Abi-Rached Bassam Hematology Oncology Life Center LLC; Abou-Issa Fadi Internal Medicine Specialists TGMC; Abraham Shaun Leonard J. Chabert Medical Center - DM; Abraham Gency University Health - Shreveport DM; Abraham Shema University Hospital and Clinics - DM; Abrams Mathew Baton Rouge Obstetrical -

Medical and Nursing Specialists, Physicians, and Physician Assistants Handbook

MEDICAL AND NURSING SPECIALISTS, PHYSICIANS, AND PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS HANDBOOK TEXAS MEDICAID PROVIDER PROCEDURES MANUAL: VOL. 2 JUNE 2021 TEXAS MEDICAID PROVIDER PROCEDURES MANUAL: VOL. 2 JUNE 2021 MEDICAL AND NURSING SPECIALISTS, PHYSICIANS, AND PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS Table of Contents 1 General Information . 12 1.1 Payment Window Reimbursement Guidelines for Services Preceding an Inpatient Admission. .12 2 Chiropractic Manipulative Treatment (CMT) . .13 2.1 Enrollment . .13 2.2 Services, Benefits, Limitations, and Prior Authorization. .13 2.2.1 Prior Authorization . 14 2.3 Documentation Requirements . .14 2.4 Claims Filing and Reimbursement . .14 2.4.1 Claims Information . 14 2.4.2 Reimbursement . 14 3 Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM) . .15 3.1 Provider Enrollment. .15 3.1.1 Enrollment in Texas Health Steps (THSteps) . 16 3.2 Services, Benefits, Limitations, and Prior Authorization. .16 3.2.1 Deliveries . 16 3.2.2 Newborn Services . 16 3.2.3 Prenatal and Postpartum Services. 16 3.2.4 Laboratory and Radiology Services . 16 3.2.5 Prior Authorization . 16 3.2.6 Documentation Requirements . 17 3.2.7 Claims Filing and Reimbursement. 17 4 Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA) . .18 4.1 Enrollment . .18 4.2 Services, Benefits, Limitations, and Prior Authorization. .18 4.2.1 Prior Authorization . 19 4.3 Documentation Requirements . .19 4.4 Claims Filing and Reimbursement . .19 4.4.1 Claims Information . 19 4.4.1.1 Interpreting the R&S Report. 19 4.4.2 Reimbursement . 19 5 Geneticists . .20 5.1 Enrollment . .20 5.1.1 Geneticists . 20 5.2 Services, Benefits, Limitations, and Prior Authorization. .21 5.2.1 Family History . -

The Length of Training Pilot: Does Anyone Really Know What Time It Takes? Peter J

SPECIAL ARTICLES The Length of Training Pilot: Does Anyone Really Know What Time It Takes? Peter J. Carek, MD, MS BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: With funding from the Ameri- insufficient innovation. Several oth- can Board of Family Medicine, the Review Committee for Family er medical educators voiced similar Medicine of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Edu- concerns.4-10 cation has undertaken a project to examine the length of training More recently, proponents of a for family medicine residents. This project comes at a time when 4-year residency training period sug- concerns are being raised regarding how well family medicine resi- gested that the additional length of dents are being prepared for independent practice, especially in training would provide a longitudi- view of the changing health care environment. The declining per- nal educational experience in conti- formance of recent graduates on the American Board of Family nuity of care with patient population Medicine certification examination and reports of narrowing of the scope of practice of family physicians have only heightened these based in community practice set- 11 concerns. This special article is meant to provide a historical re- ting. Further, a lengthened period view of the issue as well as an overview of the project. of training would provide the capac- ity for trainees to customize their (Fam Med 2013;45(3):171-2.) residency experience by selecting a “value-added” component to their training. urrently, the required length that a more efficient approach would While some family medicine edu- of training for a family medi- allow an excellent program to be pre- cators support increasing the length Ccine resident is 3 years. -

MINUTES of the FOURTH MEETING of the LEGISLATIVE HEALTH and HUMAN SERVICES COMMITTEE September 16, 2009 Santa Ana Star Civic Center, Rio Rancho

MINUTES of the FOURTH MEETING of the LEGISLATIVE HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES COMMITTEE September 16, 2009 Santa Ana Star Civic Center, Rio Rancho September 17-18, 2009 University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Family Practice Center, Albuquerque The fourth meeting of the Legislative Health and Human Services Committee (LHHS) was called to order by Representative Danice Picraux, chair on September 16, 2009 at 8:55 a.m. A voting quorum was present. Present Absent Rep. Danice Picraux, Chair Sen. Dede Feldman, Vice Chair Sen. Rod Adair Rep. Nora Espinoza Rep. Joni Marie Gutierrez Sen. Linda M. Lopez (9/18) Rep. Antonio Lujan Sen. Gerald Ortiz y Pino Advisory Members Rep. Ray Begaye Sen. Sue Wilson Beffort Rep. Jose A. Campos (9/17, 9/18) Rep. John A. Heaton Rep. Eleanor Chavez Sen. Gay G. Kernan Rep. Nathan P. Cote Rep. Rodolfo "Rudy" S. Martinez Rep. Miguel P. Garcia Rep. Jeff Steinborn Rep. Keith J. Gardner (9/16) Sen. Clinton D. Harden, Jr. Rep. Dennis J. Kintigh Rep. James Roger Madalena Sen. Cisco McSorley Rep. Bill B. O'Neill Sen. Mary Kay Papen Sen. Nancy Rodriguez (9/17, 9/18) Sen. Sander Rue Rep. Mimi Stewart Sen. David Ulibarri (9/16, 9/18) Rep. Gloria C. Vaughn (Attendance dates are noted for those members not present for the entire meeting.) Staff Michael Hely, Staff Attorney, Legislative Council Service (LCS) Karen Wells, Researcher, LCS Jennie Lusk, Staff Attorney, LCS Josh Sanchez, Intern, LCS Guests The guest list is in the meeting file. Handouts Handouts are in the meeting file. Wednesday, September 16 Welcome and Introductions Representative Picraux welcomed everyone. -

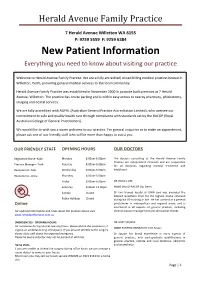

New Patient Information Everything You Need to Know About Visiting Our Practice

Herald Avenue Family Practice 7 Herald Avenue Willetton WA 6155 P: 9259 5559 F: 9259 6384 New Patient Information Everything you need to know about visiting our practice Welcome to Herald Avenue Family Practice. We are a fully accredited, mixed billing medical practice located in Willetton, Perth, providing general medical services to the local community. Herald Avenue Family Practice was established in November 2000 in purpose built premises at 7 Herald Avenue, Willetton. The practice has onsite parking and is within easy access to nearby pharmacy, phlebotomy, imaging and dental services. We are fully accredited with AGPAL (Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited), who oversee our commitment to safe and quality health care through compliance with standards set by the RACGP (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners). We would like to wish you a warm welcome to our practice. For general enquiries or to make an appointmen t, please ask one of our friendly staff who will be more than happy to assist you. OUR FRIENDLY STAFF OPENING HOURS OUR DOCTORS Registered Nurse- Kylie Monday 8.00am-6.00pm The doctors consulting at the Herald Avenue Family Practice are independent clinicians and are responsible Tuesday 8.00am-6.00pm Practice Manager- Trish for all decisions regarding medical treatment and Wednesday 8.00am-6.00pm healthcare. Receptionist- Mel Receptionist- Anna Thursday 8.00am-6.00pm Friday 8.00am-6.00pm DR DANIEL LIM Saturday 8.00am-12.00pm MBBS (Hon) FRACGP Dip Derm Sunday Closed Dr Lim trained locally at UWA and was awarded the Edward Gawthorn Prize for the highest marks achieved Public Holidays Closed during his GP training in WA. -

Patient-Centered Medical Homes

The CouNcil Of StaTe goverNments NOV 2010 CAPITOL research HealtH State Initiatives in Patient-Centered Medical Homes State Medicaid programs, which provide health insurance for the poor using state and federal funds, constantly strive to cut costs and achieve savings. That’s because Medicaid’s share of total state spending has more than doubled in the past 20 years, reaching nearly 22 percent of all state budget funds.1 States are pursuing patient-centered medical home initiatives as one approach to improving the way health care is delivered while controlling rising health care costs. Based on the premise of rewarding doctors to keep their patients healthy—rather than paying exclusively for treating them when they’re sick, this approach has many supporters, including policymak- ers, employers, physicians, patients and insurers.2 What is a patient-centered medical home? At the core of the medical home is the patient’s personal, comprehensive, long-term relationship with a primary care physician and a philosophy of care focused on preventing illness and helping patients take an active role in promoting their own good health. The primary care physician and staff act as a home base—or the patient’s medical “home”—where the patient can access care during extended hours, patients actively participate in their care, and the medical home coordinates medical care across all health care settings such as hospitals, outpatient managed care approaches and health maintenance facilities and nursing homes. organizations, but asks providers to focus on improv- Four major primary care physician groups—the ing care rather than managing costs. -

Pharmacists in Family Practice: a Resource

The IMPACT Program Pharmacists in Family Practice: A Resource PHARMACIST TOOLKIT THE BASICS Working in Family Practice — What You Need to Know • Family physicians and other staff enjoy working with pharmacists in family practice. • This has been tried and tested through the IMPACT project and other studies. • Patients benefit from the expertise of both physicians and pharmacists early enough in their care to prevent and reduce drug-related problems. • Integrating may be challenging, but it is also rewarding for everyone involved. • There are many resources and supports available, starting with this toolkit. The goal of the IMPACT program, as the acronym suggests, is to Integrate family Medicine and Pharmacy to Advance primary Care Therapeutics. A growing body of research supports our belief that having pharmacists working in family practice settings enhances patient care.1 This toolkit is the product of more than 10 years of planning and collaboration between investigators, government and community leaders. IMPACT – Integrating family Medicine and Pharmacy to Advance primary Care Therapeutics. The IMPACT program is a demonstration project funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (OMHLTC) through the Primary Health Care Transition Fund. © 2006. The views expressed in the reports or materials are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND KEY CONTACTS IMPACT Principal Investigators: Intersectorial Advisory Committee: 2004/2005 IMPACT Pharmacists and Family Practice