Components of Metaphoric Proposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

Grimm's Fairy Stories

Grimm's Fairy Stories Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm The Project Gutenberg eBook, Grimm's Fairy Stories, by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Illustrated by John B Gruelle and R. Emmett Owen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Grimm's Fairy Stories Author: Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm Release Date: February 10, 2004 [eBook #11027] Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES*** E-text prepared by Internet Archive, University of Florida, Children, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 11027-h.htm or 11027-h.zip: (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h/11027-h.htm) or (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h.zip) GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES Colored Illustrations by JOHN B. GRUELLE Pen and Ink Sketches by R. EMMETT OWEN 1922 CONTENTS THE GOOSE-GIRL THE LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER HANSEL AND GRETHEL OH, IF I COULD BUT SHIVER! DUMMLING AND THE THREE FEATHERS LITTLE SNOW-WHITE CATHERINE AND FREDERICK THE VALIANT LITTLE TAILOR LITTLE RED-CAP THE GOLDEN GOOSE BEARSKIN CINDERELLA FAITHFUL JOHN THE WATER OF LIFE THUMBLING BRIAR ROSE THE SIX SWANS RAPUNZEL MOTHER HOLLE THE FROG PRINCE THE TRAVELS OF TOM THUMB SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED THE THREE LITTLE MEN IN THE WOOD RUMPELSTILTSKIN LITTLE ONE-EYE, TWO-EYES AND THREE-EYES [Illustration: Grimm's Fairy Stories] THE GOOSE-GIRL An old queen, whose husband had been dead some years, had a beautiful daughter. -

PBS Lesson Series

PBS Lesson Series ELA: Grade 2, Lesson 6, Rumpelstiltskin Lesson Focus: Students will build knowledge about fairy tales. Practice Focus: Sequencing story events in notes and rewriting for a retelling of Rumpelstiltskin Objective: Students will use Rumpelstiltskin to take notes on a graphic organizer with a focus on summarizing the fairy tale. Academic Vocabulary: royal, royalty, straw TN Standards: 2.RL.KID.2, 2.RL.KID.3, 2.FL.PWR.3 Teacher Materials: The teacher packet for ELA, Grade 2, Lesson 6 Chart paper – one page is prepared with the word “Rumpelstiltskin” written and divided into syllables Markers Two pieces of paper to model with Student Materials: Two pieces of paper and a pencil, and a surface to write on Crayons, markers, or colored pencils The student packet for ELA, Grade 2, Lesson 6 which can be found at www.tn.gov/education Teacher Do Students Do Opening (1 min) Students gather materials for the Hello! Welcome to Tennessee’s At Home Learning Series for lesson and prepare to engage with literacy! Today’s lesson is for all our 2nd graders out there, the lesson’s content. though everyone is welcome to tune in. This lesson is the first in this week’s series. My name is ____ and I’m a ____ grade teacher in Tennessee schools. I’m so excited to be your teacher for this lesson! Welcome to my virtual classroom! If you didn’t see our previous lesson, you can find it on www.tn.gov/education. You can still tune in to today’s lesson if you haven’t seen any of our others. -

Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme

Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 6 Article 4 1-1-1998 Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme Kimberly J. Pierson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles Part of the Law Commons, and the Legal Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pierson, Kimberly J. (1998) "Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme," Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy: Vol. 6 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIRCLES 1998 Vol. VI REVENGE AND PUNISHMENT: LEGAL PROTOTYPE AND FAIRY TALE THEME By Kimberly J. Pierson' The study of the interrelationship between law and literature is currently very much in vogue, yet many aspects of it are still relatively unexamined. While a few select works are discussed time and time again, general children's literature, a formative part of a child's emerging notion of justice, has been only rarely considered, and the traditional fairy tale2 sadly ignored. This lack of attention to the first examples of literature to which most people are exposed has had a limiting effect on the development of a cohesive study of law and literature, for, as Ian Ward states: It is its inter-disciplinary nature which makes children's literature a particularly appropriate subject for law and literature study, and it is the affective importance of children's literature which surely elevates the subject fiom the desirable to the necessary. -

Fairy Tale Versions~

FAIRY TALES/FOLK TALES Fairy Tales are a type of folktale in which magic plays a great part. Compiled by Sheila Kirven GENERAL Anderson, Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Juv.A544ste Armstrong, Gerry The magic bagpipe Juv. 788.9 .A735m Browne, Anthony Into the Forest Juv. B882i (Story incorporates elements of familiar tales) Casserley, Anne Roseen Juv. 398.21 .C344r Chapman, Gaynor The Luck Child Juv. 398.21.C466l 1968 De Regniers, Beatrice Little Sister and the Month Brothers Juv. D431Li Schenk The House in the Wood and Other Old Fairy Stories Juv. 398.2.G864h Little Lit: Folklore and Fairy Tale Funnies Juv.398.21.F666 Hennessy, B. G. Once Upon a Time Map Book: Take a Tour Juv.H515o of Six Enchanted Lands (Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Jack and then Beanstalk, Aladdin, Snow White) Jacobs, Joseph The buried moon; a tale told by Joseph Jacobs. Juv. 398.21 .J17b Jacobs, Joseph Indian fairy tales Juv.398.2 .J17i 1969 MacDonald, George, The golden key Juv. M135g Matsutani, Miyoko, The crane maiden. Juv. 98.21 .M434c My Storytime Collection of First Favorite tales Juv. 398.2.M995 2002 O’Malley, Kevin Once upon a cool motorcycle dude Juv. O543o (Two classmates try to tell a fairy tale to their class with some imaginative twists to some well-known fairy tale elements!) Oxenbury, Helen. Helen Oxenbury nursery story book. Juv. 398.21 .O98h San Jose, Christine Little Match Girl Juv. 398.21.A544j San Souci, Robert D. White Cat Juv.398.21.SS229w 1990 Singer, Marilyn Follow Follow: A book of Reverso poems Juv.811.54.S617f (Poems -

An Analysis of Figurative Language on Cinderella, Rumpelstiltskin, the Fisherman and His Wife and the Sleeping Beauty the Woods

AN ANALYSIS OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE ON CINDERELLA, RUMPELSTILTSKIN, THE FISHERMAN AND HIS WIFE AND THE SLEEPING BEAUTY THE WOODS BY CHARLES PERRAULT AND THE BROTHERS GRIMM Poppy Afrina Ni Luh Putu Setiarini, Anita Gunadarma University Gunadarma University Gunadarma University jl. Margonda Raya 100 jl. Margonda Raya 100 jl. Margonda Raya 100 Depok, 16424 Depok, 16424 Depok, 16424 ABSTRACT Figurative language exists to depict a beauty of words and give a vivid description of implicit messages. It is used in many literary works since a long time ago, including in children literature. The aims of the research are to describe about kinds of figurative language often used in Cinderella, Rumpeltstiltskin, The Fisherman and His Wife and The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods By Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm and also give a description the conceptual meaning of figurative language used in Cinderella, Rumpeltstiltskin, The Fisherman and His Wife and The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods By Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. The writer uses a descriptive qualitative method in this research. Keywords: Analysis, Figurative Language, Children. forms of communication, however some 1. INTRODUCTION children’s literature, explicitly story 1.1 Background of the Research employed to add more sensuous to Human beings tend to communicate each children. other through language. Likewise they Referring to the explanation use language as well as nonverbal above, the writer was interested to communication, to express their analyze figurative language used on thoughts, needs, culture, etc. Charles Perrault and The Brothers Furthermore, language plays major role Grimm’s short stories, therefore the to transfer even influence in a writer chooses this research entitled humankind matter. -

Wcnzi (Download) Puss in Boots: a Timeless Fairy Tale (Timeless Fairy Tales) (Volume 6) Online

wcNzi (Download) Puss in Boots: A Timeless Fairy Tale (Timeless Fairy Tales) (Volume 6) Online [wcNzi.ebook] Puss in Boots: A Timeless Fairy Tale (Timeless Fairy Tales) (Volume 6) Pdf Free K. M. Shea audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1023832 in Books 2015-12-31Original language:English 8.00 x .71 x 5.25l, #File Name: 1519419171314 pages | File size: 26.Mb K. M. Shea : Puss in Boots: A Timeless Fairy Tale (Timeless Fairy Tales) (Volume 6) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Puss in Boots: A Timeless Fairy Tale (Timeless Fairy Tales) (Volume 6): 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful. Not My Favorite, But Still GoodBy LexarFor anyone who (also) didn't read the second book, this is a prologue of sorts to the whole series, as the primary story occurs three-ish years prior to Beauty and the Beast. I guess I'm still a little confused as to that, but I like the story enough to ignore it.First, this wasn't what I expected, but I'm glad. I ways support gender-bending traditional fairy tales, and Gabrielle is a fun lead, a young woman who is strong when we meet her and only grows stronger. Even though she doesn't like people, she still manages to show them compassion and empathy, and she's hard-working and down-to-Earth. She's sensible, likeable, and well-written. Gabrielle joins the line of kicka$$ heroines from books 1, 4, and 5. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

About the Book: from Favorites Like "Puss in Boots" and "Goldilocks" To

FAIRY TALE COMICS – READING GROUP GUIDE About the Book: From favorites like "Puss in Boots" and "Goldilocks" to obscure gems like "The Boy Who Drew Cats," Fairy Tale Comics has something to offer every reader. Seventeen fairy tales are wonderfully adapted and illustrated in comics format by seventeen different cartoonists, including Raina Telgemeier, Brett Helquist, Cherise Harper, and more. Edited by Nursery Rhyme Comics' Chris Duffy, this jacketed hardcover is a beautiful gift and an instant classic. For Discussion: Which of the fairy tale comic retellings is your favorite and why? There are many wicked witches, sneaky stepmothers, and creepy creatures in this book. Which villain of all of the comics do you think is the worst of them all? There are also many smart and cunning heroes, who do you think is the cleverest in all the comics? Who would win in a battle of wits? Many fairy tales teach very valuable lessons, such as the fairy tales of Baba Yaga and The Prince and the Tortoise. What lessons do you think these fairy tales present? Can you think of any other stories, or other fairy tales that teach important lessons? In many of the fairytales the characters find themselves in situations they are not sure how to get out of. What would you do if you were Hansel and Gretel stuck in the evil witch’s house, or sent to Baba Yaga who likes to eat children, or were forced to guess someone’s name like in Rumpelstiltskin? What fairy tales not included in the book would you remake into a comic? What parts of the tale would you keep the same and what would you change? Fairy tales are often made into movies, such as Snow White, Cinderella, and many others. -

Fairy Tales Then and Now(Syllabus 2019)

Spring 2019 Professor Martha Helfer Office: AB 4125 Office hours, MW 1:30-2:30 p.m. and by appointment [email protected] Fairy Tales Then and Now MW5, 2:50-4:10 pm, AB 2225 01:470:225:01 (index 10423) 01: 470: 225: 02 (index 13663) 01:470:225:03 (index 18813) 01:470:225:04 (index 21452) 01: 470: H1 (index 13662) 01:195:246:01 (index 10485) 1 Course description: This course analyzes the structure, meaning, and function of fairy tales and their enduring influence on literature and popular culture. While we will concentrate on the German context, and in particular the works of the Brothers Grimm, we also will consider fairy tales drawn from a number of different national traditions and historical periods, including the American present. Various strategies for interpreting fairy tales will be examined, including methodologies derived from structuralism, folklore studies, gender studies, and psychoanalysis. We will explore pedagogical and political uses and abuses of fairy tales. We will investigate the evolution of specific tale types and trace their transformations in various media from oral storytelling through print to film, television, and the stage. Finally, we will consider potential strategies for the reinterpretation and rewriting of fairy tales. This course has no prerequisites. Core certification: Satisfies SAS Core Curriculum Requirements AHp, WCd Arts and Humanities Goal p: Student is able to analyze arts and/or literature in themselves and in relation to specific histories, values, languages, cultures, and/or technologies. Writing and Communication Goal d: Student is able to communicate effectively in modes appropriate to a discipline or area of inquiry. -

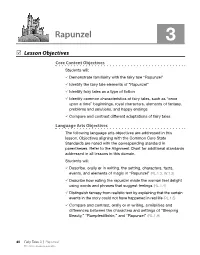

Rapunzelapunzel 3

RRapunzelapunzel 3 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Demonstrate familiarity with the fairy tale “Rapunzel” Identify the fairy tale elements of “Rapunzel” Identify fairy tales as a type of f ction Identify common characteristics of fairy tales, such as “once upon a time” beginnings, royal characters, elements of fantasy, problems and solutions, and happy endings Compare and contrast different adaptations of fairy tales Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Describe, orally or in writing, the setting, characters, facts, events, and elements of magic in “Rapunzel” (RL.1.3, W.1.3) Describe how eating the rapunzel made the woman feel delight using words and phrases that suggest feelings (RL.1.4) Distinguish fantasy from realistic text by explaining that the certain events in the story could not have happened in real life (RL.1.5) Compare and contrast, orally or in writing, similarities and differences between the characters and settings of “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rumplestiltskin,” and “Rapunzel” (RL.1.9) 40 Fairy Tales 3 | Rapunzel © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Compare and contrast, orally or in writing, similarities and differences between the read-alouds and a trade book for the story “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rumplestiltskin,” or “Rapunzel” (RL.1.9) Discuss personal responses to how they received their names and compare that to Rumpelstiltskin’s and Rapunzel’s names (W.1.8) Clarify information about “Rapunzel” by asking questions that begin with where (SL.1.1c) While listening to “Rapunzel,” orally predict what the man will do to save his wife and then compare the actual outcome to the prediction Core Vocabulary delight, n. -

Rumpelstiltskin

Rumpelstiltskin The Grimm Brothers Once there was a miller who was poor, but who had a beautiful daughter. Now it happened that he had to go and speak to the King, and in order to make himself appear important he said to him, "I have a daughter who can spin straw into gold." The King said to the miller, "That is an art which pleases me well; if your daughter is as clever as you say, bring her to-morrow to my palace, and I will try what she can do." And when the girl was brought to him he took her into a room which was quite full of straw, gave her a spinning-wheel and a reel, and said, "Now set to work, and if by to-morrow morning early you have not spun this straw into gold during the night, you must die." Thereupon he himself locked up the room, and left her in it alone. So there sat the poor miller's daughter, and for the life of her could not tell what to do; she had no idea how straw could be spun into gold, and she grew more and more miserable, until at last she began to weep. But all at once the door opened, and in came a little man, and said, "Good evening, Mistress Miller; why are you crying so?" "Alas!" answered the girl, "I have to spin straw into gold, and I do not know how to do it." "What will you give me," said the manikin, "if I do it for you?" "My necklace," said the girl.