Annie Besant DR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Third Object of the Theosophical Society

March 2011 THE THIRD OBJECT OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY To investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity. ― Third Object of the Theosophical Society The wording of the Theosophical Society’s three Objects was revised a number of times during the early years of the Society, but they have remained essentially unchanged since 1896. Many of our members associate this Object primarily with psychic powers such as clairvoyance, clairaudience, precognition, telepathy and the like. Certainly the scope of the third Object includes these types of interesting phenomena, but it really goes much deeper than that. In the March 1953 issue of The American Theosophist (AT) , seventy-eight years after the founding of the Society, the Theosophical writer Rohit Mehta observed, “We have yet to understand the full significance of the third Object.” Oddly enough, this may still be the case today. Over the years, deep students of Theosophy have given us hints as to the inner meaning of the third Object. In Human Regeneration , Radha Burnier suggests that “we must see the connection between the three Objects . to the unfoldment of the human consciousness.” In the October 1970 issue of the AT , Joy Mills suggested that the third Object relates to both “a way of knowing” and “a way of living.” By knowing she meant, not an accumulation of intellectual data, but rather a “process of inner comprehension.” Another insight was given by Hugh Shearman in his AT article of June 1949: “Occult truths are never hidden from us by anybody. We reveal or conceal them ourselves individually by what we are and what we are not yet.” In other words, the methods used to gain ordinary knowledge are not sufficient to compre- hend the hidden laws of nature and unfold the latent powers within. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 135 NO. 7 APRIL 2014 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 M. P. Singhal The many lives of Siddhartha 7 Mary Anderson The Voice of the Silence — II 13 Clara Codd Charles Webster Leadbeater and Adyar Day 18 Sunita Maithreya Regenerating Wisdom 21 Krishnaphani Spiritual Ascent of Man in Secret Doctrine 28 M. A. Raveendran The Urgency for a New Mind 32 Ricardo Lindemann International Directory 38 Editor: Mr M. P. Singhal NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Common Hoope, Adyar —A. Chandrasekaran Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Dr Chittaranjan Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. Their bond of union is not the profession of a common belief, but a common search and aspiration for Truth. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Estimates Committee (1965-66)

E.C. No. 461 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE (1965-66) HUNDREDTH REPORT (THIRD LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF EDUCATION BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI April, 1966IChmtra, 2888 (Saka) Price: Rs. 190 LIST OF AUTHORISED AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF LOK SABH' SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS SI. Name of Agent SI. Name of Agent Agcju No. No. No. ANDHRA PRADESH 13. Deccan Book Stall, 65 Ferguson College Road, Andhra University General Poona-4. Cooperative Stores Ltd., • Waltair (Visakhapatnam). RAJASTHAN 2. G.R. Lakshmipathy Chetty 94 and Sons, General 14. Information Centre, Go- 38 Merchants and News vernment of Rajasthan, Agents, Newpet, Chan- Tripolia, Jaipur City. dragiri. Chitlittoor District. UTTAR PRADESH ASSAM 3 Western Book Depot, 15. Swastik Industrial Works, Pan Bazar, Gauhati. 59, Holi Street, Meerut City. BIHAR 16. Law Book Company Sardar Patel Marg, 4. Amar Kitab Ghar, Post 37 Allahabad-1. Box 78, Diagonal Road, Jamshedpur. WEST BENGAL GUJARAT 5. Vijay Stores, Station Road, 35 17. Gramhaloka, 5/1, Ambica lo Anand. Mookherjee Road, Bel- gharia, 24 Parganas. 6. The New Order Book 63 Company, Ellis Bridge, 18. W. Newman & Company 44 Ahmedabad-6. Ltd., 3, Old Court House Street, Calcutta. MADHYA PRADESH 7. Modern Book House, Shiv 19. Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 13 6/iA, Banchharam Akrur Vilas Palace, Indore City. Lane, Calcutta-12. DELHI MAHARASHTRA 20. Jain Book Agency, Con M/s. Sunderdas Gianchand, 6 naught Place, New Delhi. 601, Girgaum | Road, Near I Princess Street, 21. Sat Narain & Sons, 3141, Bombay-2. Mohd. Ali Bazar, Mori Gate, Delhi. 9. The International Book 22 House (Private) Limited, 22. A^ma Ram Sc Sons, Kash- 9, Ash Lane, Mahatma mere Gate, Delhi-6. -

It Will Be My Greatest Happiness to Know That in Its Own Humble Way, Kalakshetra Is Helping to Make More Beautiful, More A

"It will be my greatest happiness to know that in its own humble way, Kalakshetra is helping to make more beautiful, more artistic, the lives of all - that in the education of the young, creative reverence for that spirit of the beautiful which knows no distinction of race, nation or faith has a pre-eminent place..." Rukmini Devi Arundale INTRODUCTION RUKMINI DEVI COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS BHARTANATYAM REPERTORY CARNATIC MUSIC VISUAL ARTS MAP OF KALAKSHETRA PART TIME COURSES SCHOOLS MUSEUM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES AND PUBLICATIONS PERFORMANCE SPACES CONTACT DETAILS ABOUT OUR FOUNDER RUKMINI DEVI ARUNDALE 1904 -1986 ukmini Devi was born in the temple town of Madurai in Rthe erstwhile Madras Presidency, now in Tamil Nadu. She spent her early years there along with her eight siblings. Her father Neelakanta Sastry who was very “forward thinking” initiated the family into the philosophy of the Theosophical Society, which freed religion from superstition. She grew up in the environment of the Theosophical Society, influenced and inspired by people like Dr. Annie Besant, Dr. George Sydney Arundale, C. W. Leadbeater and other thinkers and theosophists of the time. In 1920, she married Dr. George Sydney Arundale. Although they faced a great deal of opposition from the conservative society of Madras, they stayed firm in their resolve and worked together in the years that followed. KALAKSHETRA'S ORIGINS n August 1935, Rukmini Devi along with her husband Dr. IGeorge Sydney Arundale and her brother Yagneswaran met with a few friends to discuss a matter of great importance to her – the idea of establishing an arts centre where some of the arts, particularly music and dance, could thrive under careful guidance. -

Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions

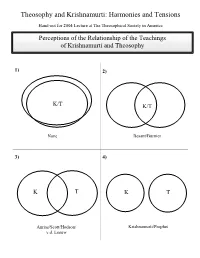

Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions Hand-out for 2004 Lecture at The Theosophical Society in America Perceptions of the Relationship of the Teachings of Krishnamurti and Theosophy 1) 2) K/T K/T None Besant/Burnier 3) 4) K T K T Anrias/Scott/Hodson/ Krishnamurti/Prophet v.d. Leeuw Theosophical Perceptions of World Teacher Project Genuine Not Genuine Annie Besant K (1980s) Rom Landau Radha Burnier Ouspensky Jean Overton Fuller uccessful Aryel Sanat S C.W. Leadbeater Rudolf Steiner Geoffrey Hodson A. Smythe Scott/Anrias E.L. Gardner Alice Bailey K (1930’s) Failed Ballard/Prophet Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti Category Theosophy Krishnamurti Motto "There is no religion higher "Truth is a pathless land" than truth" Aspects of truth "some portions … "truth has no aspects" proclaimed" Theoretical vs. personal "truth by direct experience" "… through observation" Comparison "Contrast alone …" " … is not understanding " Higher and lower selves 3-fold nature of Self "an idea, not a fact" Reincarnation Part of "pivotal doctrine" "immaterial" Spiritual path(s) Many or One "Truth is a pathless land" (Spiritual) Evolution "perpetual progress for each "Doesn’t exist" "Life can incarnating Ego" not have a plan" Ladders "No single rung of the ladder "the ladder of hierarchical … can be skipped" achievement, is utterly false" Masters "undeniable existence" "Your own projections" Mediators Send out periodically Exploiters Nationalism/Patriotism To be awakened Absurd and cruel Ceremonies "have their place … [and] use "illusions" -

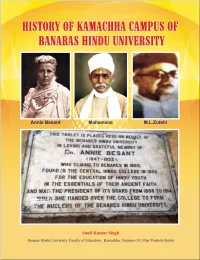

History of Kamachha Campus of Banaras Hindu University

HISTORY OF KAMACHHA CAMPUS OF BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY (BHU Centenary Year 2015-2016) (Faculty of Education Centenary Year 2017-2018) BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY, FACULTY OF EDUCATION KAMACHHA, VARANASI-10, U.P. (INDIA) Sunil Kumar Singh M.Sc.(Botany), M.Ed., Ph.D.& D.Litt.(Education),DIY, FCSEDE,CIC. Professor of Education, Banaras Hindu University [email protected] , [email protected], mobile-9450580931 History of Kamachha Campus of Banaras Hindu University, 2020 1 Title: HISTORY OF KAMACHHA CAMPUS OF BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY Patron: Prof. S.K. Swain, Head and Dean, Faculty of Education, BHU, Kamachha, Varanasi. Author's Name: Sunil Kumar Singh Published By: Self-publisher Publisher's Address: Residential: N-13/20 A-2P Pragya Nagar, Near Chaura Mata Mandir, Sundarpur, Varanasi-10, U.P., Official: Professor, Faculty of Education, Banaras Hindu University, Kamachha, Varanasi-10, U.P., India Advisory Members: Dr. S.B. Patel (Former Finance Officer, BHU), Prof. Rakesh Raman (Former Professor In- charge, BHU Press), Prof. P.S.Ram (Faculty of Education), Dr. Neeru Wahal (Principal, CHBS), Mrs. Abha Agrawal (Principal, CHGS), Dr. G. Narasimhulu (Former Actg. Principal, Sri RSV) Edition Details: 5 August, 2020 (First Edition of E-Book) ISBN: 978-93-5408-335-8 Copyright: Author and Faculty of Education, BHU, Kamachha, Varanasi, U.P., India. Prize: Rs.100/ for paperback/ Free online dissemination of E-Book Photography: Mr. Manish Kumar Gautam and Mr. Virendra Kumar Tripathi Printer's Details: Seema Press, Ishwargangi, Varanasi, U.P., India History of Kamachha Campus of Banaras Hindu University, 2020 2 Banaras Hindu university (Established by Parliament vide Notification No. -

The Light Bearer

THE LIGHT BEARER SUMMER - 2014 National Library of Canada reference No. 723428. Canada Post Publication mail Agreement number: 40040169 The Light Bearer Satyat Nasti Paro Dharma—There is no Religion Higher than Truth `` the Logo is the Egyptian cross, or Ankh, whispering of the breath of life. It is the resurrection of the Spirit. Volume 20.7 Any and all opinions, ideas, and concepts expressed in this magazine are strictly those of the authors. If I have put in something of yours for which I did not give credit, please let me know that I might do so. May every Theosophical Student find inner wholeness. Copyright © 2014 Canadian Theosophical Association. All Rights Reserved. Theosophy is not a religion, nor a philosophy, but ‘Divine Wisdom’ . Our Seal has 7 elements which represent the spiritual unity of all life. “Om”, at the edit Compiler-Margaret Mason top, is a word which “creates, sustains, and Johnson transforms”. Remember this as you use it in your meditations. Very ancient is the whirling cross or how How the Universe is ‘Swastika’ within the circle below the ‘Om’. Manifested – H.P.B. (Swastika is a compound of SU—a particle meaning Tim Congratulations Tim Boyd! ‘auspicious,’ blessed,’ ‘virtuous,’ ‘beautiful’ and ‘rightly’; and ‘astika’ derived from the verb-root AS— quest The Question – Helen to be; hence ‘that which is blessed and excellent.’- Pearl (poem) ‘Swa’ is one’s Self.) Inside the whirling energy of the Swastika, all is the stillness we hope to find Canada Canada – S.E. Price within our meditations. Our serpent swallows its tail conv Conversations with Radha to the right, representing constant new beginnings. -

Theosophist Oct

THE INDIAN THEOSOPHIST OCT. & NOVEMBER VOL. 113 NO. 10 & 11 CONTENTS MESSAGES 291-292 A STEP FORWARD 293 S.Sundaram PRACTICAL THEOSOPHY 294-299 Radha Burnier THE SECRET OF REGENERATION 300-304 Rohit Mehta THEOSOPHY: ORTHODOXY OR HERESY? 305-307 Joy Mills THEOSOPHY IN DAILY LIFE 308-313 Chittaranjan Satapathy FOUNDERS’ TRAVELS IN INDIA: BEGINNINGS OF THE INDIAN SECTION 314-320 Pedro Oliveira LOOKING AHEAD 321-329 G. Dakshina Moorthy EDUCATION IN THE LIGHT OF THEOSOPHY AND PRESENT DAY CHALLENGES 330-335 Sushila Singh THE TOS IN INDIA 336-342 T.K. Nair EMPOWERING THE VISION 343-346 S.Sundaram NEWS AND NOTES 347-356 Editor S. SUNDARAM Cover Page : The Path to SHANTI KUNJ MESSAGE Dear Brother Sundaram On the significant occasion of the 125th anniversary of the Indian Section , I send my best wishes to all the programmes planned for its commemoration, particularly the seminar on “Looking Ahead” and your special double issue of The Indian Theosophist. The world in which we are living is in crisis, a crisis created by the inadequate unfoldment of our consciousness. New ways of seeing and interacting with each other are forming and require responsible, stable individuals to bring them into their daily lives in order to create a new world. It is my hope that in your time together at the seminar and other functions, and also through your journal, you can develop the mind capable of calling forth that “New World” already in our midst. Peace and blessings, Tim Boyd International President THE INDIAN THEOSOPHIST, Oct. & Nov./2015/ 291 MESSAGE 292/ THE INDIAN THEOSOPHIST, Oct. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 136 NO. 6 MARCH 2015 CONTENTS Address to New Members 3 Tim Boyd On Relationship, Part I —Discovering Our Divinity 6 Raphael Langerhorst Transcending Science —A New Dawn - II 12 Jacques Mahnich The Theosophical Society — Finding its Aim? 19 Robert Kitto Weaving the Fabric Glorious 25 Joy Mills Books of Interest 31 Theosophical Work around the World 32 Index 37 International Directory 40 Editor: Mr Tim Boyd NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Nicholas Roerich. ‘Monhegan, Maine’, USA, 1922 Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Mr Tim Boyd Vice-President: Dr Chittaranjan Satapathy Secretary: Ms Marja Artamaa Treasurer: Mr K. Narasimha Rao Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Vice-President: [email protected] Secretary: [email protected] Treasurer: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Editorial Office: [email protected], Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. -

Central Hindu School Board

BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY VARANASI – 221 005 CENTRAL HINDU SCHOOL BOARD 1 The School Board consists of the following: (a) The VICE-CHANCELLOR/RECTOR, who shall be the Chairman. (b) VICE-CHAIRMAN, who shall be nominated by the Chairman from amongst the serving Professors of the University. (c) REGISTRAR, who shall be the Member-Secretary. (d) FINANCE OFFICER (e) FOUR MEMBERS, nominated by the Chairman, for tenure of three years. (f) PRINCIPALS/ADHYAKSHA, of the Central Hindu School, Central Hindu Girls’ School and Ranveer Sanskrit Vidyalaya.(*) 2. FIVE MEMBERS of the School Board including the CHAIRMAN and the MEMBER SECRETARY shall form the quorum. 3. (i) The STANDING COMMITTEE of the School Board consist of:- (1) VICE-CHAIRMAN, School Board, who shall be its Chairman. (2) REGISTRAR (3) FINANCE OFFICER (4) PRINCIPALS/ADHYAKSHA of the School/Vidyalaya. (5) ONE MEMBER from amongst the nominated members of the School Board. (ii) FOUR MEMBERS of the Standing Committee of the School Board shall form the quorum. NAME OF THE SCHOOL TEACHERS CENTRAL HINDU BOYS SCHOOL (K) Name Subject Designation DR. NAWAL KISHORE SHAHI PRINCIPAL SRI N.SRINIVAS TELANG Sanskrit PGT DR. SRI KRISHNA RAI Chemstry PGT DR. YOGENDRA PRASAD MISHRA Physics PGT DR.VIDYA SAGAR SINGH Accounting PGT SRI JAI SHANKAR PD. MISHRA Sanskrit PGT DR. RAMAYAN TRIPATHI Physics PGT DR. OM PRAKASH English PGT DR. UDAI NATH SINGH Physics PGT DR. TAPOMOY KUMAR LAHIRI Physics PGT DR. DAYA SHANKAR RAI Mathematics PGT DR. RAM ASHRE Chemstry PGT SMT. ASHA SINGH English PGT DR. AJAB NARAIN PANDEY Hindi PGT DR. SARVESH SINGH Phy. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 130 NO. 9 JUNE 2009 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 323 Radha Burnier Right Action is Creation without Attachment 327 Ricardo Lindemann The Religion of the Artist 332 C. Jinarajadasa Studies in The Voice of the Silence, 17 341 John Algeo Fragments of the Ageless Wisdom 348 Comments on Viveka-chudamani 349 Sundari Siddhartha Brother Raja Our Fourth President 353 A TS Member Theosophical Work around the World 357 International Directory 358 Editor: Mrs Radha Burnier NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: C. Jinarajadasa, fourth President of the Theosophical Society Adyar Archives Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. On the Watch-Tower RADHA BURNIER Seeing is an Art When we observe fully which we It is necessary to look at ordinary do very rarely or perhaps not at all the things with new eyes. When we look mind is no more present and working. properly, ordinary things cease to be Then the person comes into fuller con- ordinary. This is part of art, but it can be sciousness of what is around him and practised even by people who cannot before him. The beauty which is every- draw, paint or do the many things that where is known. The object of beauty is people who are called artists do. This is not important in the same way, because one of the main points in the article on art everything becomes part of the one beauty (printed later in this issue) written by our which encompasses all things.