Theosophy Moving Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Illuminate

1 Illuminate 2 Illuminate Visakha Devi Dasi Nabhasvati Devi Dasi Mondakini Devi Dasi Shyamasundara Das Ranchor Das Sarvamangala Devi Dasi Nikhil Gohil Kanchanbja Das Sutapa Das Ananda Monet Hema Devlukia Madhava Dayaita Devi Dasi Shyampriya Devi Dasi Jagatpriya Devi Dasi Kishori Yogini Devi Dasi Rakhi Sharma Sandra, Sanj and Mita Niskincana Caitanya Das Dimple Parmer 3 Illuminate EDITOR’S LETTER Finally! 2020 is over and 2021 has begun. With the new year comes new start from whatever stage we are currently in, in our own individual lives. goals, new hopes, new aspirations and...a new edition of Illuminate to re- As they say – the past doesn’t define our future; the actions we take today invigorate the spiritual connection in you! With all this newness and the are what designs our future. But this article doesn’t just talk about how arrival of spring, we’re all about birth in this issue. So following on from our important goal setting is, it also looks at what kind of goals we need to set article in July of last year in which we looked at how ISKCON was started by and aspire towards. our founder Srila Prabhupada, in this issue, we delve into how our temple, Sometimes though, nothing inspires us quite like the stories of others. Bhaktivedanta Manor came into existence. Some of the senior devotees who Since March 8th was International Women’s Day, we thought it was a were present at the time, tell us, in the article, Bhaktivedanta Manor: How wonderful opportunity to shine a light on some of the most inspirational it all began, about their initial thoughts, the struggles they faced and risks and empowered female devotees in ISKCON. -

Für Sonntag, 21

GEORGE HARRISON-Box THE APPLE YEARS Um zu bestellen, einfach Abbildung anklicken Abbildungen: Box; Kollage mit Box, Booklet und CDs. Freitag, 19. September 2014: Box (7 CDs & 1 DVD) GEORGE HARRISON - THE APPLE YEARS. 84,90 € inkl. Versand und gut verpackt Inhalt der Box: CD WONDERWALL MUSIC, CD ELECTRONIC SOUND, Doppel-CD ALL THINGS MUST PASS, CD LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD, CD DARK HORSE, CD EXTRA TEXTURE (READ ALL ABOUT IT), DVD, Booklet. Die CDs sind auch einzeln erhältlich jeweils mit den 20-Seiten-Booklet. Die DVD und das zusätzliche Büchlein gibt es nicht einzeln sondern nur in der Box. Freitag, 19. September 2014: CD (remastert) mit 20-Seiten-Booklet WONDERWALL MUSIC BY GEORGE HARRISON. Apple / Universal, Europa. Freitag, 1. November 1968: Vinyl-LP WONDERWALL MUSIC BY GEORGE HARRISON. Apple TCSAPCOR 1 (geplant STAP 1), Großbritannien. *Dezember 1967: EMI Abbey Road Studios, London, Großbritannien und **Dienstag, 9. - Montag, 15. Januar 1968: EMI Recording Studios, Universal Insurance Building, Phirozeshah Mehta Road, Fort, Bombay 400001, Indien: Track 1: Microbes (George Harrison) (3:39). Track 2: Red Lady Too (George Harrison) (1:53). Track 3: Table And Pakavaj (George Harrison) (1:04). Track 4: In The Park (George Harrison) (4:08). Track 5: Drilling A Home (George Harrison) (3:07). Track 6: Guru Vandana (George Harrison) (1:04). Track 7: Greasy Legs (George Harrison) (1:27). Track 8: Ski-ing And Gat Kirwani (George Harrison) (3:06). Track 9: Dream Scene (George Harrison) (5:27). Track 10: Party Seacombe (George Harrison) (4:34): Track 11: Love Scene (George Harrison) (4:16). Track 12: Crying (George Harrison) (1:14). -

Theosophical Notes No. 6 Winter 2018-19

Volume 2, Issue 2 (6) 17th February 2019 Winter 2018-19 Newsletter 17th February 2019 1 Theosophical Notes No. 6, Winter 2018-19 A home for commentaries & research on the Theosophical Movement There is one thing that should be remembered in the midst of all difficulties, and it is this—“When the lesson is learned, the necessity ceases.” Robert Crosbie, pupil of William Q Judge, ex-President of the Boston Theosophical Society, founder of the United Lodge of Theosophists Please circulate to friends and colleagues who may be interested Quarterly Newsletter from the ULT in London, UK and New York, USA. Winter 2018-19 Newsletter 17th February 2019 2 Editor’s note The aim of these Notes is to give the timeless Perennial Wisdom just as it was when released from its centuries of obscuration, and to show it can help in all departments of life, viz. science, philosophy & religion, or rather psychology. In times of change and difficulty it is natural to seek principles in which we can have confidence; so what can reliably guide us to live wisely and intelligently? Is it to feel a duty to our suffering neighbour? To free ourselves of hypocrisy and injustice? Relieving others of it by example? Reasonable and tolerant debates? A free judiciary and press? Are these not the deep-running strands of social fabric that hold society together on which we ultimately depend? But the inner Path shows these many civil ‘goods’ are consequences of just a few virtues, the paramitas of “The Voice of the Silence.” With them comes the willingness to bravely enter new spaces and deeper ideals, to actively fight for and cultivate balance, patience, and charity and begin a mental renewal. -

The Third Object of the Theosophical Society

March 2011 THE THIRD OBJECT OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY To investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity. ― Third Object of the Theosophical Society The wording of the Theosophical Society’s three Objects was revised a number of times during the early years of the Society, but they have remained essentially unchanged since 1896. Many of our members associate this Object primarily with psychic powers such as clairvoyance, clairaudience, precognition, telepathy and the like. Certainly the scope of the third Object includes these types of interesting phenomena, but it really goes much deeper than that. In the March 1953 issue of The American Theosophist (AT) , seventy-eight years after the founding of the Society, the Theosophical writer Rohit Mehta observed, “We have yet to understand the full significance of the third Object.” Oddly enough, this may still be the case today. Over the years, deep students of Theosophy have given us hints as to the inner meaning of the third Object. In Human Regeneration , Radha Burnier suggests that “we must see the connection between the three Objects . to the unfoldment of the human consciousness.” In the October 1970 issue of the AT , Joy Mills suggested that the third Object relates to both “a way of knowing” and “a way of living.” By knowing she meant, not an accumulation of intellectual data, but rather a “process of inner comprehension.” Another insight was given by Hugh Shearman in his AT article of June 1949: “Occult truths are never hidden from us by anybody. We reveal or conceal them ourselves individually by what we are and what we are not yet.” In other words, the methods used to gain ordinary knowledge are not sufficient to compre- hend the hidden laws of nature and unfold the latent powers within. -

Complete List Catalog

Cultivate an open mind Complete List Catalog www.questbooks.net 2012 House Publishing Theosophical TABLECOMPLETE OF CONTENTS QUEST TITLE LIST QUEST BOOKS are published by THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P.O. Box 270, Wheaton, Illinois 60187-0270. The Society is a branch of a world fellowship and membership organization dedicated to promoting the unity of humanity and encouraging the study of Complete Quest Title List ............................................................ 3 religion, philosophy, and science so that we may better understand ourselves and our relationships within Complete Adyar Title List ...........................................................13 this multidimensional universe. The Society stands for complete freedom of individual search and belief. Complete Study Guide List .......................................................21 For further information about its activities, write to the above address, call CD / Audio Program List.............................................................21 1-800-669-1571, e-mail [email protected], or consult its Web page: www.theosophical.org. DVD / Video Program List ..........................................................28 Author Index ..................................................................................36 VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT Order Forms....................................................................................46 WWW.QUESTBOOKS.NET Visit our website for interactive features now available Ordering Information....................................Inside -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 135 NO. 7 APRIL 2014 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 M. P. Singhal The many lives of Siddhartha 7 Mary Anderson The Voice of the Silence — II 13 Clara Codd Charles Webster Leadbeater and Adyar Day 18 Sunita Maithreya Regenerating Wisdom 21 Krishnaphani Spiritual Ascent of Man in Secret Doctrine 28 M. A. Raveendran The Urgency for a New Mind 32 Ricardo Lindemann International Directory 38 Editor: Mr M. P. Singhal NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Common Hoope, Adyar —A. Chandrasekaran Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Dr Chittaranjan Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. Their bond of union is not the profession of a common belief, but a common search and aspiration for Truth. -

Theosophy Moving Forward

Independent Theosophical Magazine Electronic Edition 2nd Qtr 2014 Moving Theosophy ahead in the 21st Forward century Main theme in this issue Our Unity Theosophy as Religion Some words on Daily Life There Is a New International President: Now What Do We Do? Similarities and differences of Theosophical traditions Theosophy Forward This independent electronic magazine offers a portal to Theosophy for all those who believe that its teachings are timeless. It shuns passing fads, negativity, and the petty squabbles of sectarianism that mar even some efforts to propagate the eternal Truth. Theosophy Forward offers a positive and constructive outlook on current affairs. Theosophy Forward encourages all Theosophists, of whatever organizations, as well as those who are unaligned but carry Theosophy in their hearts, to come together. Theosophists of any allegiance can meet and respectfully exchange views, because each of us is a centre for Theosophical work. It needs to be underscored that strong ties are maintained with all the existing Theosophical Societies, but the magazine's commitment lies with Theosophy only and not with individuals or groups representing these various vehicles. Theosophy Forward 2nd Quarter 2014 Regular Edition of Theosophy Forward Cover Photo: Leaves Adyar, by courtesy of Richard Dvoøák Published by Theosophy Forward Produced by the Rman Institute Copyright © Theosophy Forward 2014 All rights reserved. Contents Page THEOSOPHY 6 Theosophy as Religion from a student 7 Our Unity by Barend Voorham 13 Our Unity by Hans van Aurich 15 Our Unity by David Grossman 17 Our Unity by Ali Ritsema 19 Some Words on Daily Life by an unnamed Master of the Wisdom 21 The Voice of the Silence 12 by John Algeo 27 L. -

El Sargento Pepper.Indd 1 29/02/16 12:27 EL SARGENTO PEPPER NUNCA ESTUVO ALLÍ

JULIÁN RUIZ Licenciado en Periodismo y Ciencias Políticas en Los Ángeles, ingeniero y productor de discos certifi cado por la RIAA de Estados Unidos. Como productor ha realizado hasta la fecha 122 discos. Ha obtenido 14 números uno en Abba John Lennon las listas de venta. Ha producido a Nino Bravo, Adele Joséphine Baker Alaska y los Pegamoides, Orquesta Mondra- Amanda Lear Kurt Cobain gón, Azul y Negro, Tino Casal, Objetivo Bir- Beach Boys Led Zeppelin ALLÍ mania, Burning, Danza Invisible, Cómplices, Bee Gees Lou Reed EL SARGENTO Miguel Ríos, Manolo Tena, entre otros muchos Bob Dylan Mama Cass artistas. Bob Geldof Marvin Gaye Bob Marley Michael Hutchence A mediados de los 90 obtuvo una serie de Brian Jones Michael Jackson éxitos como artista y compositor con los pro- Bruce Springsteen yectos El Bosco, CCCP, Esperanto, Uffox XXI, ESTUVO PEPPER Mick Jagger Bryan Ferry Mike Oldfi eld Atlántida, The Globe Icon, así como con Rita Chrissie Hynde Nina Simone Marley, Zucchero, Tim Booth (James) y Dr. Crosby, Stills & Nash John, por citar solo algunos. Ha producido Paul McCartney David Bowie también la versión española de los musicales Peter Gabriel Dusty Springfi eld El 1 de junio de 1967 se publica Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, NUNCA Grease, Popcorn y Starmania. Pink Floyd Elton John el mítico álbum de los Beatles que revolucionó la historia de la música Elvis Presley Prince popular. El disco fue recibido como una obra de arte total (fi cción, Ha publicado artículos en Cambio 16, Inter- Fleetwod Mac Sam Cooke concepto visual, arreglos, vanguardia, performance...), que congregaba viú, Qué y Opinión. -

Theosophy Intro.Pdf

THEOSOPHY AN INTRODUCTORY STUDY COURSE FOURTH EDITION by John Algeo Department of Education THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P. O. Box 270, Wheaton, IL 60189-0270 Copyright © 1996, 2003, 2007 by the Theosophical Society in America Based on the Introductory Study Course in Theosophy by Emogene S. Simons, copyright © 1935, 1938 by the Theosophical Society in America, revised by Virginia Hanson, copyright © 1967, 1969 by the Theosophical Society in America. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without written permission except for quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA For additional information, contact: Department of Information The Theosophical Society in America P. O. Box 270 Wheaton, IL 60189-0270 E-mail: [email protected] Web : www.theosophical.org 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. What Is Theosophy? 7 2. The Ancient Wisdom in the Modern World 17 3. Universal Brotherhood 23 4. Human Beings and Our Bodies 30 5. Life after Death 38 6. Reincarnation 45 7. Karma 56 8. The Power of Thought 64 9. The Question of Evil 70 10. The Plan and Purpose of Life 77 11. The Rise and Fall of Civilizations 92 12. The Ancient Wisdom in Daily Life 99 Bibliography 104 FIGURES 1. The Human Constitution 29 2. Reincarnation 44 3. Evolution of the Soul 76 4. The Three Life Waves 81 5. The Seven Rays 91 6. The Lute of the Seven Planes 98 3 INTRODUCTION WE LIVE IN AN AGE OF AFFLUENCE and physical comfort. We drive bulky SUVs, talk incessantly over our cell phones, amuse ourselves with DVDs, eat at restaurants more often than at home, and expect all the amenities of life as our birthright. -

It Will Be My Greatest Happiness to Know That in Its Own Humble Way, Kalakshetra Is Helping to Make More Beautiful, More A

"It will be my greatest happiness to know that in its own humble way, Kalakshetra is helping to make more beautiful, more artistic, the lives of all - that in the education of the young, creative reverence for that spirit of the beautiful which knows no distinction of race, nation or faith has a pre-eminent place..." Rukmini Devi Arundale INTRODUCTION RUKMINI DEVI COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS BHARTANATYAM REPERTORY CARNATIC MUSIC VISUAL ARTS MAP OF KALAKSHETRA PART TIME COURSES SCHOOLS MUSEUM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES AND PUBLICATIONS PERFORMANCE SPACES CONTACT DETAILS ABOUT OUR FOUNDER RUKMINI DEVI ARUNDALE 1904 -1986 ukmini Devi was born in the temple town of Madurai in Rthe erstwhile Madras Presidency, now in Tamil Nadu. She spent her early years there along with her eight siblings. Her father Neelakanta Sastry who was very “forward thinking” initiated the family into the philosophy of the Theosophical Society, which freed religion from superstition. She grew up in the environment of the Theosophical Society, influenced and inspired by people like Dr. Annie Besant, Dr. George Sydney Arundale, C. W. Leadbeater and other thinkers and theosophists of the time. In 1920, she married Dr. George Sydney Arundale. Although they faced a great deal of opposition from the conservative society of Madras, they stayed firm in their resolve and worked together in the years that followed. KALAKSHETRA'S ORIGINS n August 1935, Rukmini Devi along with her husband Dr. IGeorge Sydney Arundale and her brother Yagneswaran met with a few friends to discuss a matter of great importance to her – the idea of establishing an arts centre where some of the arts, particularly music and dance, could thrive under careful guidance. -

Masonic A. Esoteric Heritage (Den Haag, 10/20-21/05)

Masonic a. Esoteric Heritage (Den Haag, 10/20-21/05) Andrea Kroon Masonic & Esoteric Heritage. A New Perspective for Art and Conservation Policies Conference 20-21 October 2005, Royal Library, Den Haag (The Netherlands) The renovation of the building of the Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij in Amsterdam (1919), carried out to accommodate the Amsterdam Municipal Archive, has stimulated a heated discussion between experts on western esotericism, art history, conservation and cultural heritage. The building was designed by the renowned Dutch architect K.P.C. de Bazel, who was a member of theosophical and masonic organizations. The architectural design, as well as the use of specific materials and decoration, encompasses a rich theosophical symbolism. Should this original symbolism be kept intact or be allowed to be radically altered to suit the needs of the Amsterdam Municipal Archive? The case has highlighted a problem area in current art and heritage policies, that will be addressed at the conference for the first time in an international context. While it is widely accepted that world religions such as christianity, islam, judaism and hinduism have profoundly influenced art and architecture, it has not been acknowledged that western esoteric currents (such as freemasonry and theosophy) have influenced many celebrated artists and architects in the same way. The traditional approach to western art is based on christian iconography, which does not reflect the much wider range of cultural and religious currents that have shaped western society and art. As a result of this oversight, surviving examples of the material culture of western esoteric currents are not recognized as an integral part of our collective cultural heritage and are insufficiently documented, studied and preserved. -

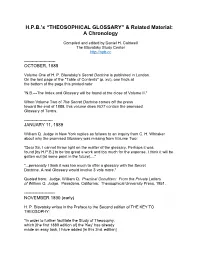

THEOSOPHICAL GLOSSARY” & Related Material: a Chronology

H.P.B.’s “THEOSOPHICAL GLOSSARY” & Related Material: A Chronology Compiled and edited by Daniel H. Caldwell The Blavatsky Study Center http://hpb.cc ------------------------ OCTOBER, 1888 Volume One of H. P. Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine is published in London. On the last page of the "Table of Contents" (p. xvi), one finds at the bottom of the page this printed note: "N.B.---The Index and Glossary will be found at the close of Volume II." When Volume Two of The Secret Doctrine comes off the press toward the end of 1888, this volume does NOT contain the promised Glossary of Terms. ---------------------- JANUARY 11, 1889 William Q. Judge in New York replies as follows to an inquiry from C. H. Whitaker about why the promised Glossary was missing from Volume Two: "Dear Sir, I cannot throw light on the matter of the glossary. Perhaps it was found [by H.P.B.] to be too great a work and too much for the expense. I think it will be gotten out [at some point in the future]...." "...personally I think it was too much to offer a glossary with the Secret Doctrine. A real Glossary would involve 3 vols more." Quoted from: Judge, William Q. Practical Occultism: From the Private Letters of William Q. Judge. Pasadena, California: Theosophical University Press, 1951. --------------------- NOVEMBER 1890 (early) H. P. Blavatsky writes in the Preface to the Second edition of THE KEY TO THEOSOPHY: "In order to further facilitate the Study of Theosophy, which [the first 1889 edition of] the 'Key' has already made an easy task, I have added [in this 2nd.