Nachthexen: Soviet Female Pilots in WWII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

Grade 12 June Paper 1 2019

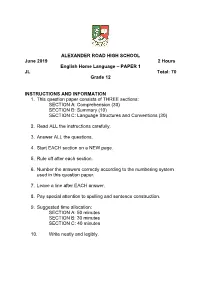

ALEXANDER ROAD HIGH SCHOOL June 2019 2 Hours English Home Language – PAPER 1 JL Total: 70 Grade 12 INSTRUCTIONS AND INFORMATION 1. This question paper consists of THREE sections: SECTION A: Comprehension (30) SECTION B: Summary (10) SECTION C: Language Structures and Conventions (30) 2. Read ALL the instructions carefully. 3. Answer ALL the questions. 4. Start EACH section on a NEW page. 5. Rule off after each section. 6. Number the answers correctly according to the numbering system used in this question paper. 7. Leave a line after EACH answer. 8. Pay special attention to spelling and sentence construction. 9. Suggested time allocation: SECTION A: 50 minutes SECTION B: 30 minutes SECTION C: 40 minutes 10. Write neatly and legibly. SECTION A: COMPREHENSION QUESTION 1: READING FOR MEANING AND UNDERSTANDING Read TEXT A below and answer the questions set. TEXT A The Night Witches: The All-Female World War II Squadron That Terrified the Nazis Gisely Ruiz, Published March 17, 2019, Updated April 11, 2019 1 The Night Witches decorated their planes with flowers and painted their lips with navigation pencils – then struck fear into the hearts of the Nazis. 2 The women of the 588th Night Bomber Regiment of the Soviet Air Forces had no radar, no machine guns, no radios, and no parachutes. All they had was a map, a compass, rulers, stopwatches, flashlights and pencils, yet they successfully completed 30,000 bombing raids and dropped more than 23,000 tons of munitions on advancing German armies during World War II. 3 The all-female Night Witches squadron was the result of women in the Soviet Union wanting to be actively involved in the war effort. -

La Voce Del Popolo

la Vocedel popolo LIMES la Vocedel popolo LIBURNICO: LE PIETRE DELLA NOSTRA storia MEMORIA www.edit.hr/lavoce Anno 9 • n. 72 Sabato, 6 aprile 2013 CONVEGNI RECENSIONE ANNIVERSARI PILLOLE INTERVISTA Riflessioni sulle terre Una radio e la «guerra Il sogno dell’angelo «Streghe della notte» Passione travolgente giuliano-dalmate fredda adriatica» dal «paradiso nero» per fermare i nazisti per l’archeologia Da Brescia un chiaro segnale Il libro di Roberto Spazzali è un Il 4 aprile di 45 anni fa veniva Estate ’42, pianura del Don: la “Scienza, quindi democrazia”: della volontà di comprendere esempio di ricerca di «serie A» assassinato Martin Luther King, straordinaria, eroica epopea di un’analisi del suo ruolo ciò che2|3 accadde in questa regione sulle nostre4|5 vicende di metà ’900 attivista e Nobel per la6 pace un gruppo di aviatrici7 russe culturale e sociale 8 del popolo 2 sabato, 6 aprile 2013 storia&ricerca la Voce CONTRIBUTI di Ivan Pavlov RIFLESSIONI di Italo Dapiran LIBERI TERRITORI E TERRITORIO LIBERO rieste è, per cause storiche, una città zione. Un’altra nazione nell’infinita storia peculiare. Ogni via è intrisa di odori, di microstati europei cessa di esistere con Tsapori e suoni che non rispecchiano l’estensione della sovranità dei due stati l’omologazione delle altre città italiane. coinvolti su di essa. Pare finita qui, fin- Questa sua diversità, che deriva non solo ché la crisi economica non comincia a dall’essere stata porto franco ed essere città divampare come un cavallo imbizzarrito: di confine, la porta a essere oggetto di un il vecchio spirito europeo si riaccende nelle miscuglio di emozioni ben polarizzate: zone autonomiste, indipendentiste o addi- c’è chi la ama, e chi non la sopporta. -

Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War PRINTER: strip in FIGURE NUMBER A-1 Shoot at 277% bleed all sides Stephen L. McFarland A Douglas P–70 takes off for a night fighter training mission, silhouetted by the setting Florida sun. 2 The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War Stephen L. McFarland AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1998 Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War The author traces the AAF’s development of aerial night fighting, in- cluding technology, training, and tactical operations in the North African, European, Pacific, and Asian theaters of war. In this effort the United States never wanted for recruits in what was, from start to finish, an all-volunteer night fighting force. Cut short the night; use some of it for the day’s business. — Seneca For combatants, a constant in warfare through the ages has been the sanctuary of night, a refuge from the terror of the day’s armed struggle. On the other hand, darkness has offered protection for operations made too dangerous by daylight. Combat has also extended into the twilight as day has seemed to provide too little time for the destruction demanded in modern mass warfare. In World War II the United States Army Air Forces (AAF) flew night- time missions to counter enemy activities under cover of darkness. Allied air forces had established air superiority over the battlefield and behind their own lines, and so Axis air forces had to exploit the night’s protection for their attacks on Allied installations. -

Nadezhda Popova - Telegraph 21/07/13 18:50

Nadezhda Popova - Telegraph 21/07/13 18:50 Nadezhda Popova Nadezhda Popova, who has died aged 91, was a member of an elite corps of Soviet women — known as the “Night Witches” — who fought as bomber pilots in the air war against Germany, and the only one to win three Orders of the Patriotic War for bravery. Nadezhda Popova (standing) with some of her fellow 'Night Witches' Photo: NOVOSTI/TOPFOTO 5:21PM BST 10 Jul 2013 Unlike Soviet men, women were not formally conscripted into the armed forces. They were volunteers. But the haemorrhaging of the Red Army after the routs of 1941 saw mass campaigns to induct women into the military. They were to play an essential role. More than 8,000 women fought in the charnel house of Stalingrad. In late 1941 Stalin signed an order to establish three all-women Air Force units to be grouped into separate fighter, dive bomber and night bomber regiments. Over the next four years these regiments flew a combined total of more than 30,000 combat sorties and dropped 23,000 tons of bombs. Nadezhda Popova, then aged 19, was one of the first to join the best-known of the three units, the 588th Night Bomber Regiment (later renamed the 46th Taman Guards Night Bomber Aviation Regiment). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/10171897/Nadezhda-Popova.html Page 1 sur 4 Nadezhda Popova - Telegraph 21/07/13 18:50 The 588th was not well equipped. Wearing hand-me-down uniforms from male pilots, the women flew 1920s-vintage Polikarpov PO-2 two-seater biplanes, which consisted of fabric strung over a plywood frame, and lacked all but the most rudimentary instruments. -

Jan-June 2020 Bibliography

Readers are encouraged to forward items which have thus far escaped listing to: Christine Worobec Distinguished Research Professor Emerita Department of History Northern Illinois University [email protected] Please note that this issue has a separate category for the "Ancient, Medieval, and Early Modern Periods." It follows the heading "General." All categories listed by Country or Region include items from the modern and contemporary periods (from approximately 1700 to the present). GENERAL Aivazova, Svetlana Grigor'evna. "Transformatsiia gendernogo poriadka v stranakh SNG: institutsional'nye factory i effekty massovoi politiki." In: Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve 4 (73) (2014): 11-23. Aref'eva, Natal'ia Georgievna. "Svatovstvo v slavianskoi frazeologii." In: Mova 22 (2014): 139-44. [Comparisons of Bulgarian, Russian, Ukrainian] Artwińska, Anna, and Agnieszka Mrozik. Gender, Generations, and Communism in Central and Eastern Europe and Beyond. London: Routledge, 2020. 352p. Baar, Huub van, and Angéla Kóczé, eds. The Roma and Their Struggle for Identity in Contemporary Europe. New York: Berghahn, 2020. 346p. [Includes: Kóczé, Angéla. "Gendered and Racialized Social Insecurity of Roma in East Central Europe;" Schultz, Debra L. "Intersectional Intricacies: Romani Women's Activists at the Crossroads of Race and Gender;" Zentai, Violetta. "Can the Tables Be Turned with 1 a New Strategic Alliance? The Struggles of the Romani Women's Movement in Central and Eastern Europe;" Magazzini, Tina. "Identity as a Weapon of the Weak? Understanding the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture: An Interview with Tímea Junghaus and Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka."] Balázs, Eszter and Clara Royer, eds. "Le Culte des héros." Special issue of Etudes & Travaux d'Eur'ORBEM (December 2019). -

Diary of a Night Bomber Pilot in World War 1

THE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE JOURNAL VOL. 3 | NO. 4 FALL 2014 DIARY OF A NIGHT BOMBER PILOT IN WORLD WAR 1 By Clive Semple United Kingdom: The History Press, 2008 320 pages ISBN 978-1-86227-425-5 Review by Major Chris Buckham, CD, MA emoirs are a two-edged sword for historians. While they provide a plethora of information relating to the “hows and whys” of decision making for the subject of a book, they also tend toward being selective in recollection and can be very Mself-serving as well as a source of justification by the author. A diary, on the other hand, is a source with great potential and use. Written in real time and with the prejudices, attitudes, frustrations, and honesty of the moment; it provides unprecedented insight into the mind of its author and is an invaluable tool to use in the development of a book. Clive Semple’s father, Leslie, joined the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) in 1917 at the age of 18 and served as a night bomber pilot flying Handley Page bombers until he resigned his commission in 1919, after a period of occupation duty in Germany. He rarely spoke about his service following the war, and it was not until his death in 1971 that the author discovered a time capsule of photos, documents, and a diary in a box in Leslie’s attic. Drawing upon all of these resources—especially the diary—Clive Semple drafted an outstanding picture of life for a young man making his way through training and wartime operations. -

Annual Report 2009

Bi-Annual 2009 - 2011 REPORT R MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA CELEBRATING 20 YEARS Director’s Message With the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Harn Museum of Art in 2010 we had many occasions to reflect on the remarkable growth of the institution in this relatively short period 1 Director’s Message 16 Financials of time. The building expanded in 2005 with the addition of the 18,000 square foot Mary Ann Harn Cofrin Pavilion and has grown once again with the March 2012 opening of the David A. 2 2009 - 2010 Highlighted Acquisitions 18 Support Cofrin Asian Art Wing. The staff has grown from 25 in 1990 to more than 50, of whom 35 are full time. In 2010, the total number of visitors to the museum reached more than one million. 4 2010 - 2011 Highlighted Acquisitions 30 2009 - 2010 Acquisitions Programs for university audiences and the wider community have expanded dramatically, including an internship program, which is a national model and the ever-popular Museum 6 Exhibitions and Corresponding Programs 48 2010 - 2011 Acquisitions Nights program that brings thousands of students and other visitors to the museum each year. Contents 12 Additional Programs 75 People at the Harn Of particular note, the size of the collections doubled from around 3,000 when the museum opened in 1990 to over 7,300 objects by 2010. The years covered by this report saw a burst 14 UF Partnerships of activity in donations and purchases of works of art in all of the museum’s core collecting areas—African, Asian, modern and contemporary art and photography. -

The Women of the 46Th Taman Guards Aviation Regiment and Their Journey Through War and Womanhood Yasmine L

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2018 Dancing in the airfield: The women of the 46th Taman Guards Aviation Regiment and their journey through war and womanhood Yasmine L. Vaughan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the Military History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Vaughan, Yasmine L., "Dancing in the airfield: The omew n of the 46th Taman Guards Aviation Regiment and their journey through war and womanhood" (2018). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 551. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/551 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dancing in the Airfield: The Women of the 46th Taman Guards Aviation Regiment and their Journey through War and Womanhood _______________________ An Honors College Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Yasmine Leigh Vaughan May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the History Department, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors College. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS COLLEGE APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Steven Guerrier, Ph.D., Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Professor, History Dean, Honors College Reader: Michael Galgano, Ph.D., Professor, History Reader: Joanne Hartog, Adjunct Professor, History Reader: Mary Louise Loe, Ph.D., Professor Emerita, History PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at James Madison University on April 14, 2018. -

Holocaust Heroes

Board of Directors Helen Hardacre Susan Schweitzer HOLOCAUST HEROES: FIERCE FEMALES Linda Stein TAPESTRIES AND SCULPTURE BY LINDA STEIN Honorary Board Loreen Arbus (H2F2) Abigail Disney Lauren Embrey OVERVIEW AS OF 6/19/17 Merle Hoffman Carol Jenkins HOLOCAUST HEROES: FIERCE FEMALES IS A NEW TRAVELING EVENT Patti Kenner UNDER THE UMBRELLA OF, AND FACILITATED BY, Ruby Lerner Pat Mitchell OUR TEAM AT THE NON-PROFIT Ellen Poss HAVE ART: WILL TRAVEL! (HAWT). Elizabeth Sackler Gloria Steinem WE WOULD LIKE TO DISCUSS THE POSSIBILITY Advisory Council OF THIS EVENT COMING TO YOU. Sue Ginsburg: Chair Mary Blake Beth Bolander Jerome Chanes The gallery exhibition (see testimonials) is made up of: Sarah Connors A. Ten Heroic Tapestries Marilyn Falik Eva Fogelman B. Twenty Spoon to Shell Sculptures Karen Keifer-Boyd C. One Protector Sculpture with Wonder Woman Shadow Michael Kimmel John McCue D. Video (7-minutes on loop) featuring Abigail Disney, Elizabeth Sackler and Jeanie Rosensaft Menachem Rosensaft Gloria Steinem and others: http://www.haveartwilltravel.org/events/holocaust- Amy Stone heroes/ Executive Director E. Holocaust Heroes Book Ann Holt F. Two Magic Scarf of Ten Heroes with Interactive Local Performance Studio Manager G. Educational Inititiative and Interactive Website (optional) Rachel Birkentall This exhibition is shipped in ten tubes and two crates weighing a total of 542 lbs. For storage, crates and tubes can be stacked within a 4’x6’x8’ area. A. Heroic Tapestries: These highlight ten females who represent different aspects of bravery during the time of the Holocaust. Each tapestry is 5 ft sq, leather, metal, canvas, paint, fabric and mixed media. -

Inferences Lost in Corn Country

Name: _______________ Snow Day Assignment #5 Inferences Lost in Corn Country by Heather Klassen And I'm sure I've been lost in this corn maze for fifty hours. I didn't even want to go on this field trip in the first place. Give me an air-conditioned classroom in the city, I said. Let me eat corn fresh from a freezer. But no, some farmer had to grow a cornfield in the shape of Washington State. He even carved highways through the cornstalks. And my teacher, Ms. Barlay, had to decide that the maze would be a great field trip. To get a better sense of our state, she said. And for fun, she added. Here comes a preschool group, each kid gripping a knot on a rope, a teacher at each end. If only our class had a knotted rope, I wouldn't be in this predicament. "Why is he sitting there?" a preschooler pipes up. "Maybe he's lost," a teacher ventures. "Can we help you find your way?" "I'm just resting," I reply. I don't exactly want to be seen following a bunch of three-year-olds out of this maze at the end of a knotted rope. I look around and spot the sign that tells me I've at least made it halfway. I would kiss that sign except that two grandmotherly-looking women step into the clearing. They look at me. "Are you lost?" one asks. I'm starting to wonder if I have "lost" printed on my forehead. Right now, I wouldn't even care. -

Night Air Combat

AU/ACSC/0604G/97-03 NIGHT AIR COMBAT A UNITED STATES MILITARY-TECHNICAL REVOLUTION A Research Paper Presented To The Research Department Air Command and Staff College In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements of ACSC By Maj. Merrick E. Krause March 1997 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US government or the Department of Defense. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES......................................................................................................... iv PREFACE....................................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT................................................................................................................... vi A UNITED STATES MILITARY-TECHNICAL REVOLUTION.................................. 1 MILITARY-TECHNICAL REVOLUTION THEORY ................................................... 5 Four Elements of an MTR........................................................................................... 9 The Revolution in Military Affairs............................................................................. 12 Revolution or Evolution? .......................................................................................... 15 Strength, Weakness, and Relevance of the MTR Concept ........................................