SANDTON: a Linguistic Ethnography of Small Stories in a Site of Luxury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUTCO PROPERTIES LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2005 PUTCO PROPERTIES LIMITED Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa (Reg No 1988/001085/06)

PUTCO PROPERTIES LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2005 PUTCO PROPERTIES LIMITED Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa (Reg No 1988/001085/06) EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT For the year ended 30 June 2005 Contents Directorate and Secretary 1 Shareholders’ diary 1 Analysis of shareholding 2 Corporate governance report 3 Chairman’s statement 5 Group value added statement 6 Directors’ statement of responsibility 7 Secretary’s statement 7 Report of independent auditors 8 Directors’ report 9 Income statements 10 Balance sheets 11 Statements of changes in equity 12 Cash flow statements 13 Accounting policies 14 Notes to the annual financial statements 16 Interest in subsidiaries 21 Dividend announcement 21 Notice of annual general meeting 33 Proxy form for annual general meeting 35 CIRCULAR RE PROPOSED NAME CHANGE Circular re proposed name change 22 Form of surrender (Pink) 31 Putco Properties Limited Annual Report 2005 DIRECTORATE AND SECRETARY Directors Dr J H de Loor (Chairman and Independent non-executive) (Appointed 1 July 2003 and resigned 30 September 2004) A B Adrian (Chairman and Independent non-executive) (Appointed 30 September 2004) A Carleo (Chief Executive Officer) E M R L Oldham (Managing Director) B C Carleo (Non-executive) L A Carleo (Non-executive) (Resigned 30 September 2004) F G Pisapia (Non-executive) (Appointed 16 September 2003 and resigned 30 September 2004) A L Carleo-Novello (Non-executive) – alternate to L A Carleo (Resigned 30 September 2004) P Senatore (Non-executive) (Appointed 30 September 2004) P Nucci (Independent non-executive) -

The Impact of Shopping Mall Developments on Consumer Behaviour in Township Areas

The impact of shopping mall developments on consumer behaviour in township areas Lebogang Mokgabudi 11096692 A research report submitted to the Gordon Institute of Business Science, University of Pretoria in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Business Administration 01 August 2011 Copyright © 2012, University of Pretoria. All rights reserved. The copyright in this work vests in the University of Pretoria. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the University of Pretoria. © University of Pretoria ABSTRACT The objective of the study was to evaluate the impact of shopping mall developments on consumer behaviour in township areas. Local and international research indicated that shopping mall developments in low-income communities result in several benefits for consumers, such as convenient location; a larger variety of goods offered, lower prices than small retailers in the area and better quality of goods, amongst others. Studies also indicated that the choice of the preferred supermarket/shopping mall is not a rational decision based only on pricing, but on a compromise of satisfying economic, social and psychological needs. A two part mixed methodology, which employed both qualitative and quantitative methods, was adopted. This included semi-structured interviews with retail experts and interview-administered questionnaires with the primary retail shopper in the household. The sample population was Alexandra Township in Gauteng, South Africa. Findings revealed that low-income consumers prefer to shop from the closest shopping mall instead of small retailers/Spaza Shops because of the lower prices and a larger variety of goods offered. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

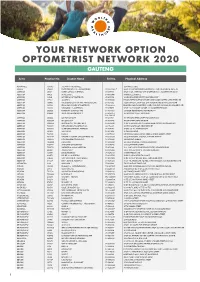

Your Network Option Optometrist Network 2020 Gauteng

YOUR NETWORK OPTION OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2020 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 -

The PUTCO Strikes: a Question of Control Carole Cooper

3 The PUTCO Strikes: a question of control Carole Cooper "We have been told by the Liaison Committee that the management of PUTCO has offered a 15% increase in wages to come into effect from 1 July 1980. We, the workers, do not know if you negotiated that for us or not. We know you did not consult us. We know, therefore, you do not know what our demands are for wages, or for improved conditions of service at the depots, or how management must show more respect for the dignity of the workers." This dissatisfaction sparked off one of the two strikes held by PUTCO bus drivers at the Putcoton depot in the last six months of 1980. Both strikes crippled transport to the black townships surrounding Johannesburg. The first strike, held in July, concerned the pay issue mentioned above, as well as union recognition, with other demands such as the transfer of a Company official and the reinstatement of workers dismissed during the strike, emerging later. The second strike, in December, broke out over an alleged breach of promise by management to investigate the said official's transfer as agreed upon at the resolution of the July strike. Although specific grievances were articulated during the respective strikes, an analysis of events and interviews with drivers reveal the existence of a complexity of grievances not clearly expressed at the time. The main thread that runs through both strikes, linking the articulated and other grievances is worker dissatisfaction with the structures of control - both management imposed and those arising out of the statutes governing labour re lations - to which PUTCO drivers are subject. -

Work in Progress, No. 38

Work in progress, No. 38 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 50 Alternative title Work In Progress Author/Creator University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg) Publisher University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg) Date 1985-08 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1985 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Rights By kind permission of Hein Marais, Julian May, and the Southern Africa Report. Format extent 48 page(s) (length/size) Page 2 of 50 WORK IN PROGRESS 38 1985 CRADOCK Resistance in the Eastern Cape EMERGENCY 1960 - 1985 Page 3 of 50 Strikes and Disputes: Natal COMPANY AND AREA UNION WORKERS DATE EVENTS AND OUTCOME Baking industry NBIEU 2 000 22.07- The legal strike of over 2 000 Durban bakery workers followed a negotiation breakdown Durban SFAWU 02.08 between employers and unions in the industrial council. -

Helpline Ioaoo O1 2 322 I

Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2,50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3,25 DECEMBER Vol. 7 PRETORIA, 10 DESEMBER 2001 No. 243 We all have the power to prevent AIDS AIDS HElPLINE Ioaoo o1 2 322 I DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure 1316232-A 243-1 2 No. 243 PIROVINCIAl GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 10 DECEMBER 2001 CONTENTS Page Gazette No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICE 7397 Gauteng Interim Minibus Taxi-Type Services Act (11/1997): Amendment to the application of special measures in the Township of Soshanguve and surrounding areas within the area of jurisdiction of the City of Tswane Metropolitan Municipality ............... ,..................................................................................................................................................... 3 BUITENGEWONE PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 10 DESEMBER 2001 No. 243 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 7397 OF 2001 DEPARTMENT OF PUBUC TRANSPORT, ROADS AND WORKS GAUTENG INTERIM MINIBUS TAXI-TYPE SERVICES ACT, 1997 (ACT NO. 11 OF 1997) AMENDMENlS TO THE APPUCATION OF SPECIAL MEASURES IN THE TOWNSHIP OF SOSHANGUVE AND SURROUNDING AREAS WITHIN THE AREA OF JURISDICTION OF THE CITY OF TSHWANE METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY I, Khabisi Mosunkutu, Member of the Executive Council for Public Transport, Roads and Works in the Province of Gauteng, having already declared the area of Jurisdiction of the City of Tshwane Metropolitan Munlclpallty in terms of Section 49 (1) of the Gauteng Interim minibus Taxi-Type Services Act, No 11 of 1997 (the Act), and having published regulations in terms Section 49 (7) of the Act under General Notice No 7263 of 2001 In the Provlnclal Gazette Extraordinary No 239 dated Os December 2001, I now make amendments to the aforementioned regulations published on 5 December 2001 as contained tn the Schedule hereto. -

Factsheet 2019 1

Factsheet 2019 1 Overview as at 31 December 2018 1 Sandton City 2 Nelson Mandela Square Liberty Two Degrees Limited (L2D), the South African precinct Sandton City is one of Africa’s leading and most prestigious shopping centres, Nelson Mandela Square (NMS) is one of the largest open public spaces in the focused, retail-centred REIT, is listed on the Johannesburg conveniently located within walking distance of the Sandton Gautrain station and country and adjoins the renowned Sandton City complex. This piazza commem- Stock Exchange (JSE) with a market capitalisation of R6.3 billion with easy access from the highways surrounding and main roads within Sandton orates heritage and celebrates international style with the warmth of African CBD. With more than 300 leading local and international retailers and 199 000m2 hospitality. It draws a cosmopolitan society to its sidewalk cafes, some of the finest (USD437 million) as at 31 December 2018. of retail and office gross lettable area (GLA), Sandton City is a one-of-a-kind restaurants in South Africa and over 88 exclusive stores. NMS is 39 000m2 in GLA The L2D portfolio comprises 17 properties, some of which are South premier fashion and leisure destination. It’s an energetic hub of Afro cosmopolitan and has a total of 96 retail and office tenants. The Square serves as a stage for a Africa’s premier and most iconic assets. These include super-regional glamour — international shopping with South African flair. Sandton City comprises host of local and international prestigious events. NMS is owned by Liberty Two shopping centres Sandton City (Africa’s leading and most prestigious Diamond Walk, Sandton’s extravagant brand offering which houses global luxury Degrees and Liberty Group. -

Store Locator

VISIT YOUR NEAREST EDGARS STORE TODAY! A CCOUNT Gauteng EDGARS BENONI LAKESIDE EDGARS WOODLANDS BLVD LAKESIDE MALL BENONI WOODLANDS BOULEVARD PRETORIUS PARK EDGARS BLACKHEATH CRESTA MAC MALL OF AFRICA CRESTA SHOPPING CENTRE CRESTA MALL OF AFRICA WATERFALL CITY EDGARS BROOKLYN EDGARS ALBERTON CITY BROOKLYN MALL AND DESIGN SQUARE NIEUW MUCKLENEUK ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING CENTRE ALBERTON EDGARS MALL AT CARNIVAL EDGARS SPRING MALL MALL AT CARNIVAL BRAKPAN SPRINGS MALL1 SPRINGS EDGARS CHRIS HANI CROSSING EDGARS CENTURION CENTRE CHRIS HANI CROSSING VOSLOORUS CENTURION MALL AND CENTURION BOULEVARD CENTURION EDGARS CLEARWATER MALL EDGARS CRADLE STONE MALL CLEARWATER MALL ROODEPOORT CRADLESTONE MALL KRUGERSDORP EDGARS EAST RAND EDGARS GREENSTONE MALL EAST RAND MALL BOKSBURG GREENSTONE SHOPPING CENTRE MODDERFONTEIN EDGARS EASTGATE EDGARS HEIDELBERG MALL EASTGATE SHOPPING CENTRE BEDFORDVIEW HEIDELBERG MALL HEIDELBERG EDGARS FESTIVAL MALL EDGARS JABULANI MALL FESTIVAL MALL KEMPTON PARK JABULANI MALL JABULANI EDGARS FOURWAYS EDGARS JUBILEE MALL FOURWAYS MALL FOURWAYS JUBILEE MALL HAMMANSKRAAL EDGARS KEYWEST EDGARS MALL OF AFRICA KEY WEST KRUGERSDORP MALL OF AFRICA WATERFALL EDGARS KOLONNADE EDGARS MALL OF THE SOUTH SHOP G 034 MALL OF THE SOUTH BRACKENHURST KOLONNADE SHOPPING CENTRE MONTANA PARK EDGARS MAMELODI CROSSING EDGARS MALL REDS MAMS MALL MAMELODI THE MALL AT REDS ROOIHUISKRAAL EXT 15 EDGARS RED SQUARE DAINFERN EDGARS MAPONYA DAINFERN SQUARE DAINFERN MAPONYA MALL KLIPSPRUIT EDGARS SOUTHGATE EDGARS MENLYN SOUTHGATE MALL SOUTHGATE MENLYN PARK SHOPPING -

Exploring the Applicability of Location-Based Services to Delineate the State Public Transport Routes Integratedness Within the City of Johannesburg

infrastructures Review Exploring the Applicability of Location-Based Services to Delineate the State Public Transport Routes Integratedness within the City of Johannesburg Brightnes Risimati 1,* and Trynos Gumbo 2 1 Department of Quality and Operations Management, University of Johannesburg, Corner of Siemert and Beit Streets, Doornfontein, Johannesburg 2028, South Africa 2 Department of Town and Regional Planning, University of Johannesburg, Corner of Siemert and Beit Streets, Doornfontein, Johannesburg 2028, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-783-326-246 Received: 30 May 2018; Accepted: 25 July 2018; Published: 1 August 2018 Abstract: In the past decade, Johannesburg has actively participated in the investment and development of the Gautrain and Rea Vaya public transportation modes. However, the state of route networks connectedness amongst the two public transport modes has not been well documented. Thus, this study aimed to delineate the extent of routes network integration among the two modes. The study adopted a phenomenological case study survey design which applied a mixed-method approach to gather spatial, qualitative and quantitative data. Crowd sourced datasets from Facebook and Twitter were collected, and analyzed using the kriging interpolation method and descriptive statistics. Key informant interviews were also used to unpack the status quo of the two modes. Results indicate that there are limited areas where the route networks between the two modes are currently integrated. Variations in income levels may be a factor currently preventing inter-transfer between the two modes. The Rea Vaya has proven successful in improving accessibility to economic opportunities, with 70% of the social media posts reflecting positive views regarding route and travel timetables. -

Dispossession, Displacement, and the Making of the Shared Minibus Taxi in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, 1930-Present

Sithutha Isizwe (“We Carry the Nation”): Dispossession, Displacement, and the Making of the Shared Minibus Taxi in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, 1930-Present A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elliot Landon James IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Allen F. Isaacman & Helena Pohlandt-McCormick November 2018 Elliot Landon James 2018 copyright Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................. ii List of Abbreviations ......................................................................................................iii Prologue .......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 ....................................................................................................................... 17 Introduction: Dispossession and Displacement: Questions Framing Thesis Chapter 2 ....................................................................................................................... 94 Historical Antecedents of the Shared Minibus Taxi: The Cape Colony, 1830-1930 Chapter 3 ..................................................................................................................... 135 Apartheid, Forced Removals, and Public Transportation in Cape Town, 1945-1978 Chapter 4 ....................................................................................................................