Safer Project: Mid-Term Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

Communities Tackling Small Arms and Light Weapons in South Sudan Briefing

Briefing July 2018 Communities tackling small arms and light weapons in South Sudan Lessons learnt and best practices Introduction The proliferation and misuse of small arms and light Clumsy attempts at forced disarmament have created fear weapons (SALW) is one of the most pervasive problems and resentment in communities. In many cases, arms end facing South Sudan, and one which it has been struggling up recirculating afterwards. This occurs for two reasons: to reverse since before independence in July 2011. firstly, those carrying out enforced disarmaments are – either deliberately or through negligence – allowing Although remoteness and insecurity has meant that seized weapons to re-enter the illicit market. Secondly, extensive research into the exact number of SALW in there have been no simultaneous attempts to address the circulation in South Sudan is not possible, assessments of demand for SALW within the civilian population. While the prevalence of illicit arms are alarming. conflict and insecurity persists, demand for SALW is likely to remain. Based on a survey conducted in government controlled areas only, the Small Arms Survey estimated that between In April 2017, Saferworld, with support from United 232,000–601,000 illicit arms were in circulation in South Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), launched a project Sudan in 20161. It is estimated that numbers of SALW are to identify and improve community-based solutions likely to be higher in rebel-held areas. to the threats posed by the proliferation and misuse of SALW. The one-year pilot project aimed to raise Estimates also vary from state to state within South awareness among communities about the dangers of Sudan. -

Vistas) Q3 Fy 2017 Quarterly Report April 1– June 30, 2017

VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q3 FY 2017 QUARTERLY REPORT APRIL 1– JUNE 30, 2017 JUNE 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q2 FY 2017 QUARTERLY REPORT APRIL 1 – JUNE 30, 2017 Contract No. AID-668-C-13-00004 Submitted to: USAID South Sudan Prepared by: AECOM International Development Prepared for: Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation (OTCM) USAID South Sudan Mission American Embassy Juba, South Sudan DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Q3 FY 2017 Quarterly Report | Viable Support to Transition and Stability (VISTAS) i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Political And Security Landscape .................................................................................... 2 National Political and Security Landscape ..................................................................................................... 2 Political & Security Landscape in VISTAS Regional Offices ...................................................................... 3 III. Program Strategy.............................................................................................................. 6 IV. Program Highlights .......................................................................................................... -

Tracking the Flow of Government Transfers Financing Local Government Service Delivery in South Sudan

Tracking the flow of Government transfers Financing local government service delivery in South Sudan 1.0 Introduction The Government of South Sudan through its Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MoFEP) makes transfers of funds to states and local governments on a monthly basis to finance service delivery. Broadly speaking, the government makes five types of transfers to the local government level: a) Conditional salary transfers: these funds are transferred to be used by the county departments of education, health and water to pay for the salaries of primary school teachers, health workers and water sector workers respectively. b) Operation transfers for county service departments: these funds are transferred to the counties for the departments of education, health and water to cater for the operation costs of these county departments. c) County block transfer: each county receives a discretionary amount which it can spend as it wishes on activities of the county. d) Operation transfer to service delivery units (SDUs): these funds are transferred to primary schools and primary health care facilities under the jurisdiction of each county to cater for operation costs of these units. e) County development grant (CDG): the national annual budget includes an item to be transferred to each county to enable the county conduct development activities such as construction of schools and office blocks; in practice however this money has not been released to the counties since 2011 mainly due to a lack of funds. 2.0 Transfer and spending modalities/guidelines Funds are transferred by the national Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning from the government accounts at Bank of South Sudan to the respective state’s bank accounts through the state ministries of Finance (SMoF). -

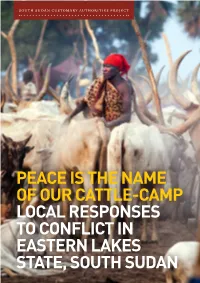

Peace Is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp By

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT PEACE IS THE NAME OF OUR CATTLE-CAMP LOCAL RESPONSES TO CONFLICT IN EASTERN LAKES STATE, SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT Peace is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local responses to conflict in Eastern Lakes State, South Sudan JOHN RYLE AND MACHOT AMUOM Authors John Ryle (co-author), Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology at Bard College, New York, was born and educated in the United Kingdom. He is lead researcher on the RVI South Sudan Customary Authorities Project. Machot Amuom Malou (co-author) grew up in Yirol during Sudan’s second civil war. He is a graduate of St. Lawrence University, Uganda, and a member of The Greater Yirol Youth Union that organised the 2010 Yirol Peace Conference. Abraham Mou Magok (research consultant) is a graduate of the Nile Institute of Management Studies in Uganda. Born in Aluakluak, he has worked in local government and the NGO sector in Greater Yirol. Aya piŋ ëë kͻcc ἅ luël toc ku wεl Ɣͻk Ɣͻk kuek jieŋ ku Atuot akec kaŋ thör wal yic Yeŋu ye köc röt nͻk wεt toc ku wal Mith thii nhiar tͻͻŋ ku ran wut pεεc Yin aci pεεc tik riεl Acin ke cam riεlic Kͻcdit nyiar tͻͻŋ Ku cͻk ran nͻk aci yͻk thin Acin ke cam riεlic Wut jiëŋ ci riͻc Wut Atuot ci riͻc Yok Ɣen Apaak ci riͻc Yen ya wutdie Acin kee cam riεlic ëëë I hear people are fighting over grazing land. Cattle don’t fight—neither Jieŋ cattle nor Atuot cattle. Why do we fight in the name of grass? Young men who raid cattle-camps— You won’t get a wife that way. -

(SAFER) Project in South Sudan

(31 October 2019) Annual Report Project Name Sustainable Agriculture or Economic Resiliency (SAFER) project in South Sudan Implementation /Funding Mechanism (Cooperative Grant Agreement/ Contract /Grant) Activity Start/ End Date 4 August 2017 to 3 August 2020 Name of Prime Implementing Partner The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Name of Implementing Sub-Partner N/A Contract/Agreement Number Grant NO. AID-668-IO-17-00001 Geographical Location The Republic of South Sudan Prepared for USAID/South Sudan, Juba Brian Dusza /Lemi Lokosang C/O American Embassy, Kololo Road Reporting period 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 Financial Expenditure for the Reporting Period To be sent separately as agreed Submitted by: Meshack Malo [email protected] 1 Acronyms AAP Accountability to Affected Populations AGRA Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa CAAFAG Children Formerly Associated with Armed Groups CBAHW Community-based Animal Health Workers CBO Community Based Organisation CBPP Community-based Participatory Planning CLA Collaboration, Learning and Adapting EMMP Environmental Monitoring and Mitigation Plan FES Fuel Efficient Stove FFS Farmer Field School GEFE Gender Equality and Female Empowerment GBV Gender-based Violence WPS Women Peace and Security IDP Internally Displaced Persons IOM International Organization for Migration LoA Letter of Agreement M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEP Monitoring and Evaluation Plan NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPA Norwegian People’s Aid NBeG Northern Bahr el Ghazal NRM -

Country Profiles

Global Coalition EDUCATION UNDER ATTACK 2020 GCPEA to Protect Education from Attack COUNTRY PROFILES SOUTH SUDAN A peace agreement signed between the government and main opposition groups and enacted in September 2018 contributed to a decrease in violence in South Sudan. However, attacks on education continued to occur during this reporting period, including the use of schools by armed forces and groups, attacks on schools, attacks on students and teachers, and sexual violence at schools. Context Fighting de-escalated between the pro-Riek Machar Sudan People’s Liberation Army in Opposition (SPLA-IO (RM)) and the government’s South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF) preceding and following the signing of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) in September 2018.1799 According to International Crisis Group (ICG), armed conflict noticeably declined in former areas of hostilities such as Bentiu, Wau, and Yei.1800 However, violence escalated again in late 2018 and early 2019 between signatories and non-signatories to the agreement, including the National Salvation Front (NAS) in Central Equatoria state and the Greater Bahr el Ghazal region, in addition to continued intercommunal violence.1801 Violence during the 2017-2019 reporting period occurred in the context of a civil war that erupted in 2013 when a power struggle between President Salva Kiir, of the majority Dinka ethnic group, and former vice-president Riek Machar, of the Nuer ethnic group, triggered ethnically-charged violence between government armed forces and the SPLA-IO (RM), and other affiliatedmilitias and local self-defense groups.1802 Civilians were impacted by the fighting during the 2017-2019 reporting period. -

Viable Support to Transition and Stability (Vistas) Q1 Fy 2019 Quarterly Report October 1 – December 31, 2018

VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q1 FY 2019 QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER 1 – DECEMBER 31, 2018 January 21, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q1 FY 2019 QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER 1– DECEMBER 31, 2018 Contract No. AID-668-C-13-00004 Submitted to: USAID South Sudan Prepared by: AECOM International Development Prepared for: Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation (OTCM), USAID South Sudan Mission American Embassy Juba, South Sudan DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Q1 FY 2019 Quarterly Report | Viable Support to Transition and Stability (VISTAS) i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms .................................................................................................................................... iii I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1 Ii. Political And Security Landscape ................................................................................... 2 Iii. Program Strategy ............................................................................................................ 3 Iv. Program Highlights ......................................................................................................... 5 To Increase -

Discover the Country Profile of South Sudan

COUNTRY PROFILE SOUTH SUDAN photo Nicola Berti SNAP- A 69-YEARS DOCTORS SHOT HISTORY WITH AFRICA Doctors with Africa CUAMM is 1,800 currently People have left CUAMM operating in Italy and other Angola, Central countries to work African Republic, on projects: Ethiopia, of these, Mozambique, 515 returned Sierra Leone, on one or more South Sudan, occasions Tanzania and Uganda through: 227 Hospitals have 23 been served Hospitals 01 42 08 02 03 64 Countries Districts of intervention 04 (for public health activities, mother-child 05 care, fight against AIDS, 06 tuberculosis 07 and malaria, 01 SIERRA LEONE training) 02 SOUTH SUDAN 03 ETHIOPIA 04 UGANDA 3 05 TANZANIA Nursing 06 ANGOLA schools 07 MOZAMBIQUE 08 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 1 University Doctors with Africa CUAMM (Mozambique) has been the first NGO working VALUES in the international health field – «With Africa»: to be recognized in Italy and the organization works 605 is the largest Italian organization exclusively with African International for the promotion and protection populations, engaging Professionals of health in Africa. It works with local human resources a long-term developmental at all levels. perspective. To this end, in Italy – Experience: CUAMM and Africa, it is engaged in training, draws on over almost research, dissemination of scientific seventy years of work to knowledge, and ensuring support developing the universal fulfilment of the countries. fundamental human right to health. – Specific, exclusive expertise in medicine Doctors with Africa is for everyone and health. who believes in values like dialogue, cooperation, volunteerism, exchange between cultures, friendship between PRIORITY people, the defense of human rights, respect for life, the choice to help ISSUES the poor, the spirit of service, and – Reproductive, maternal, those who support the organization’s newborn, child and action criteria. -

UNICEF South Sudan Humanitarian Situation July 2019

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION REPORT JULY 2019 A health worker is trained on infection prevention and control in the context of Ebola, as part of UNICEF and South South Sudan’s Ebola prevention and preparedness efforts. Photo: UNICEF South Sudan/Wilson Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report JULY 2019: SOUTH SUDAN SITREP #134 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.83 million • In July 2019, UNICEF in collaboration with the Ministry of Health Internally displaced persons (IDPs) (national and state levels), WHO and other partners continued to create (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, July 2019) awareness, engage and sensitize communities on Ebola in high-risk states reaching 208,669 people (101,938 men; 106,731 women). • On 23 July, 32 children were released from pro-Machar SPLA-iO in 2.32 million South Sudanese refugees in Mirmir, Unity State. All children were reunited with their families and are receiving reintegration services including comprehensive case neighbouring countries (UNHCR Regional Portal, South Sudan Situation management. 31 July 2019) • 26 July marked National Girls’ Education Day. In Juba, the event was hosted by the Jubek State Ministry of Education along with education 6.87 million partners. Approximately 1,085 girls from 15 schools took part in a rally South Sudanese facing acute food which included dance, drama, songs and poetry performances. insecurity or worse (May-July 2019 Projection, Integrated Food Security Phase Classification) UNICEF’s Response with Partners in 2019 Cluster for 2019 UNICEF and partners for 2019 -

Western Lakes Population Movement, Food Security and Livelihoods Profile

Western Lakes Population Movement, Food Security and Livelihoods Profile ^Juba South Sudan, July 2019 Introduction Spikes in inter and intra-communal violence (ICV) alongside economic Key Findings and climatic shocks in western Lakes State have reportedly driven • Escalation in ICV in western Lakes State since 2012, primarily large-scale displacement and restricted access to food for both host driven by decreasing access to resources, has caused communities (HCs) and internally displaced people (IDPs). In the sudden-onset displacement and atypical seasonal population January and May 2019 releases of the Integrated Phase Classification movement. (IPC) for South Sudan,1 direct outcome indicators for food security • Inaccessible seasonal pasture for livestock due to ongoing in Cueibet and Rumbek North counties indicated severe food insecurity has shifted seasonal cattle migration patterns, consumption gaps and recurrent pockets of IPC Phase 5 in Cueibet leading to increases in cattle mortality and limited seasonal County, signifying the potential for catastrophic food insecurity. The onset of the 2019 lean season and continuous reports of ICV access to food (milk). and displacement in western Lakes State has brought increasing • Repeated episodes of ICV have triggered a pervasive fear humanitarian attention to the area. The lack of information on the of insecurity, restricting HH mobility and limiting access to populations most affected by the insecurity and gaps in access to food traditional livelihood activities. was raised within the Food Security and Livelihoods (FSL) Cluster, • Food availability and access across the assessed locations triggering a joint assessment between REACH and the Vulnerability is highly limited, with northern Cueibet County likely to be the Analysis and Mapping (VAM) Unit in World Food Programme (WFP). -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity South Sudan Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Resolutions of Western Lakes State Grassroots Peace Initiative (Yei River State) Date 17/05/2018 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/local conflict ( Sudan Conflicts (1955 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Multiple issues) Conflict nature Inter-group Peace process 151: South Sudan: Post-secession Local agreements Parties Signed by the community's leaders of Western Lakes State as follows: Jul Machok Lieny - Senior Chief, Western Lakes State Manyiel Lieny Wol - Elder and Chief, Western Lakes State Elizabeth Agok Anyijong - Women leader, Western Lakes State Moses Deng Akeu - Youth Representative, Western Lakes State Third parties Witnessed by: Most Rev. Bishop Elias Taban Parangi - Head of Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC) Peace Desk Hon. Mabor Meen Wol - Minister of LG&LE and Governor's Representative Description A short community agreement which calls for community reconciliation, dialogue, disarming of youth and reimposition of security and law by the local state government. The agreement also provides for measures to be carried out by the EPC in facilitating a space of healing and management of infrastructural rebuilding. Agreement document SS_180517_Resolutions of Western Lakes State Grassroots Peace Initiative.pdf [] Groups Children/youth Rhetorical Page 1, Resolutions of Western Lakes State Grassroots Peace Initiative, 3.The workshop resolved that, civilians and youth carrying unauthorized arms must be disarmed immediately by the Government. Page 1, Resolutions of Western Lakes State Grassroots Peace Initiative, 6. (a)Youth engagement in income generation activities and training of organized forces to observe law and order (b)EPC to lobby for organizations that will open micro-finance for small business to widows and orphans in Western Lake State.