Nonpoint Source Pollution Assessment Report Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Water Quality Summary of the Bear River Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council, 2010

A Water Quality Summary of the Bear River Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council, 2010 Table of Contents Page List of Tables and Figures 3 Introduction 4 Bear River Watershed 5 Description 5 Water Quality of the Bear River 7 Alkalinity and pH 7 Dissolved oxygen 9 Conductivity and chloride 9 Nutrients 12 Heavy metals 15 Biological monitoring 16 Literature and Data Referenced 20 Appendix 1: Parameters monitored by organizations 22 2 List of Tables Page Table 1. Bear River Watershed land-cover statistics 5 Table 2. Population trends in Emmet and Charlevoix Counties 12 Table 3. Biological data from the Bear River and other streams 19 List of Figures Page Figure 1. The Bear River Watershed 6 Figure 2. Monitoring sites in the Bear River Watershed 8 Figure 3. Conductivity levels in the Bear River 10 Figure 4. Chloride levels in the Bear River 11 Figure 5. Chloride trends in the Bear River at Mineral Well Park 12 Figure 6. Total Phosphorus levels in the Bear River 14 Figure 7. Total nitrogen and nitrate-nitrogen levels in the Bear River 15 3 INTRODUCTION Water quality data have been compiled to assess the overall water quality of the Bear River Watershed, as well as that of individual monitoring sites. Water quality data have been collected from the Bear River and its tributaries over the last several decades and are available from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council (TOMWC), and Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBB). Water quality data from the MDEQ includes “Legacy” data, which is historical data (prior to year 2000) from the United States Environmental Protection Agency STORET database. -

Hemingway's Michigan

Map Locations P ETOSKEY, 49770 1.1 Pere Marquette Railroad Station—100 Depot St. Hemingway’s (Little Traverse History Museum) 2.2 Grand Rapids & Indiana Railroad Station—Corner of Bay St. and Lewis St. (Pennsylvania Plaza Offices) 3.3 The Perry Hotel—100 Lewis St. Michigan 4.4 The Annex—432 East Lake St. (City Park Grill) 5.5 McCarthy’s Barber Shop—309 Howard St. 6.6 Jesperson’s Restaurant—312 Howard St. 7.7 Carnegie Library Building—451 East Mitchell St. 8.8 Potter’s Rooming House—602 State St. (This is a private residence and not open to the public.) WALLOON LAKE, 49796 EH1 Hemingway Historical Marker—Walloon Village, Melrose Township Park on Walloon Lake VILLAGE OF HORTON BAY, 49712 EH2 Walloon Lake Public Access & Boat Launch—Go SE of Horton Bay on the Boyne City-Charlevoix Rd. for approximately one mile; turn (due east) on to Sumner Rd. and follow it to the end. Approx. 2.25 mi. 9.9 Pinehurst and Shangri-La—5738 Lake St., (First two dwellings on the east side of Lake St. as it descends down the road to the bay on Lake Charlevoix.) EH3 Lake Charlevoix Public Access Site & Boat Launch—At the end of Lake St. down from Pinehurst and Shangri-La. 10.10 Horton Bay General Store—5115 Boyne City Rd. (on Ernest Hemingway the Charlevoix-Boyne City Rd., village of Horton Bay) (Clockwise from top left) 11 11. Horton Creek—Approximately 5408 Boyne City Rd. -Ernest with cane, suitcase, and a wine bottle in his pocket. BAY VIEW ASSOCIATION, 49770 Petoskey, 1919 EH4 Evelyn Hall On the campus of the Bay View Assoc. -

2021- 2025 Recreation Plan Resort Township Emmet County

2021- 2025 Recreation Plan Resort Township Emmet County Adopted: December 8, 2020 Prepared by: Resort Township Recreation Committee With the assistance of: Richard L. Deuell, Planning Consultant RESORT TOWNSHIP RECREATION PLAN 2021-2025 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page ............................................................................................................... i Table of Contents .................................................................................................. ii Section 1. Introduction and History ................................................................................... 1-1 2. Community Description ..................................................................................... 2-1 3. Administrative Structure .................................................................................... 3-1 4. Recreation and Resource Inventories ............................................................... 4-1 5. Description of the Planning and Public Input Process ....................................... 5-1 6. Goal and Objectives .......................................................................................... 6-1 7. Action Program ................................................................................................. 7-1 8. Plan Adoption .................................................................................................... 8-1 Appendix A: Survey Findings ...................................................................................... A-1 Appendix B: Supporting -

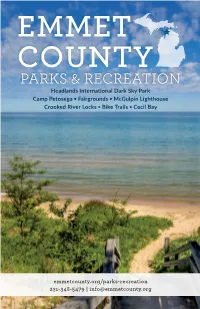

2019 Parks and Recreation Guide

EMMET COUNTY PARKS & RECREATION Headlands International Dark Sky Park Camp Petosega ▪ Fairgrounds ▪ McGulpin Lighthouse Crooked River Locks ▪ Bike Trails ▪ Cecil Bay emmetcounty.org/parks-recreation 231-348-5479 | [email protected] 21546_ParksandRecGuide.indd 1 3/4/19 8:17 AM Welcome to Emmet County, Michigan Welcome to our Parks and Recreation Guide! In these pages, we’re going to give you a snapshot tour of Emmet County’s most special amenities, from our International Dark Sky Park at the Headlands to our vast, connected trail network, to our parks and beaches, towns and natural resources. This is a special place, tucked into the top of Michigan’s mitten in the Northwest corner, a place where radiant sunsetsWhere and extraordinary fallquality color complement fluffyof lifeand abundant snowfall and the most satisfying shoreline summers you’ve ever spent. It’s a place that for centuries has been home to the is Odawa Indian tribe and the descendants of settlers from French and British beginnings.everything Here, the outdoors is yours to explore thanks to foresight and commitment from local officials who think one of the best things we can do for the public is to provide access to lakes, rivers, nature preserves, trails, parks and all the points in between. Here, there’s no shortage of scenery as you traverse our 460 square miles, from the tip of the Lower Peninsula at the Mackinac Bridge, to quaint little Good Hart on the west, the famed Inland Waterway at our east, and Petoskey and Bay Harbor to the south. We hope you enjoy your tour -

Fall 2012/Winter 2013

SUPERIOR TO SARNIA : The Line 5 Pipeline Millions of miles of oil and gas transport pipelines crisscross – how are you going to ensure all of us in Northern Michigan that Michigan and the rest of the United States. By their nature, these what happened to the Kalamazoo River won’t happen to Lake Michigan, underground pipelines tend to go unnoticed until a leak or ruptur e Lake Huron, Douglas, Burt, and Mullett Lakes and the rivers Line occurs, or there is controversy over building or expanding a 5 crosses on its way to Sarnia? pipeline. Recently, Enbridge’s Line 5 drew public attention when the company expanded the line’s capacity by 10% earlier this year Enbridge insisted that they have no intention of using Line 5 to to meet rising demand. Line 5 starts in Superior, Wisconsin, crosses transport the heavy oil produced from tar sands, though there Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, goes under the Straits of Mackinac are no long term assurances to that effect. Enbridge has improved and travels between Burt and Mullett Lakes on its way to Sarnia, its detection system as well as its integrity monitoring process Ontario. This line expansion raised concerns about the possible since the spill in Marshall. However, the line which transports almost future transport of tar sands through the line and the increased 541,000 barrels a day of light and medium crude or natural gas risk of a disaster similar to Enbridge’s Line 6B, which caused the could still pose a risk if leaks and ruptures occur. The steps taken 2nd largest inland oil spill in US history. -

BEAR CREEK TOWNSHIP, MICHIGAN Master Plan Update

Master Plan Update DRAFT 2020 BEAR CREEK TOWNSHIP, MICHIGAN Acknowledgements Bear Creek Township Planning Commission Tom Urman, Chair Planning Commission David Coveyou, Vice Chair Planning Commission Jeff Haven, Secretary Planning Commission Mitch Brown, Planning Commission Judy Mays, Planning Commission Lawrence Olliffe, Planning Commission Emma Kendziorski, Planning Commission Bear Creek Township Board Dennis Keiser, Supervisor Joseph Hoffman Jr, Trustee Don Nowland, Trustee Connie Golding, Treasurer Emma Kendziorski, Clerk Bear Creek Township 373 North Division Road Petoskey, MI 49770 (231) 347-0592 Prepared with assistance from Networks Northwest PO Box 506 Traverse City, MI 49685-0506 Telephone: 231.929.5000 www.networksnorthwest.org INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1: THE PURPOSE OF A MASTER PLAN Page 1 CHAPTER 2: COMMUNITY CHARACTER AND EXITING LAND USE MAPS Page 4 CHAPTER 3: NATURAL FEATURE ANALYSIS Page 15 CHAPTER 4: COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT Page 24 CHAPTER 5: AGRICULTURE Page 27 CHAPTER 6: SOCIOECONOMIC PROFILE Page 31 CHAPTER 7: HOUSING Page 41 CHAPTER 8: TRANSPORTATION AND UTILIITES ANALYSIS Page 46 CHAPTER 9: INFRASTRUCTURE Page 54 CHAPTER 10: POPULATION PROJECTIONS AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT Page 55 CHAPTER 11: GUIDING PRINCIPLES Page 61 CHAPTER 12: FUTURE LAND USE Page 66 Introduction Simply put, the following statement describes what Petoskey offer urban amenities for residents to makes Bear Creek Township unique and why enjoy. people want to keep it this way. This statement Because this place is so important to residents and was developed from public input sessions held in business owners, people are very expressive in 2008 and still holds true today. More than 45 relating their views. This is a place that people people described what they thought made Bear care about. -

Charlevoix County (Part)

Grand Traverse Bay Traverse Grand NORWOOD Lake Shore D Lakeshore Dr r G Produced by: Center for Shared Solutions and Technology Partnerships, Michigan Department of Technology, and Budget Management, Technology, of Department Michigan Partnerships, andTechnology Solutions Center Shared for by: Produced e n n e T t i t m R b W trim Ln d e An r T h l W i m a i h L b ak t i e e n e s S r k l h e a e y o O k C l d r e P r D e e e k i S x i D e D h N H r i w n y r r o e r D w B T a y v r i e w D i r im Creek o B m An Antr a t r o y G i b m s R l e L Brant Rd n h b d o e e i g r o h e D L i n r r M c ic L higan e B Trl n r a r R G y Source: 2009TIGER/Line, U.S. Census Bureau, MichiganGeographic Framework, v10a D h L D u Ridge y e r r G a C a d Island Fisherman r e K e L k k r il e k R d e o e n n n s r y Ln K e n D i n o e g a r r o e w x L n r R n t t F B R Norwood Twp S d R G a a d c 31 l e w a y d L n c o a u t S c t l a Torch w R h k Lake a Twp d R R Lord Rd n 31 s d d EASTPORT o n M G R W i t B m a e r e e d R p e d ATWOOD n l n e n Torch n Lake e B H e V t a t i r R l Eastpo t l rt a r C C r R d e R n ek P t Jolli i ffe Rd l d n a i d a P p E A r s i o n p r a o n t d s B a s e t wo t t R r r s B R T d v R o o Fis i h R y w e d e r d m r o e I a c w d n n n h s r d F Farrell Rd s w Is R L R la R e a R o d n Beatty Rd d k o r d d d e d r S D Cr y r eek P R A d c c C h u e r c h R s d Warner Rd s E M c Beadle Rd G e s a s c h Torch e Little Lake d W er R i tt l o C k i P n x s o n C r e e k r R e e d k BARNARD Church Rd Lake Mud Banks Twp -

Little Traverse Bay Watershed Protection Plan

Little Traverse Bay Watershed Protection Plan March 31, 2004 Updated December 31, 2005 Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council 426 Bay Street Petoskey, MI 49770 Table of Contents List of Partners Executive Summary ... ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 1 Chapter One: Getting to Know the Little Traverse Bay Watershed ...... ............ ............ ............ 3 1. Introduction... ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 3 A. What is a Watershed Management Plan? .. ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 4 B. Geologic History and Geographic Description.........……..... ............ ............ ............ ............ 9 C. Water Quality Monitoring in the Watershed ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 11 D. Interesting Features Around the Bay.......... ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 14 E. Fish of Little Traverse Bay ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 15 F. Waves, and Seiches, and Ice ........ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 15 2. Designated Uses and Water Quality Summary ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 16 A. Watershed Concerns........ ............ ............ ............ ........... -

1987 House Enrolled Bill 4235

Act No. 108 Public Acts of 1987 Approved by the Governor July 10, 1987 Filed with the Secretary of State July 13, 1987 STATE OF MICHIGAN 84TH LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION OF 1987 Introduced by Rep. O’Neill Reps. Rocca and Browne named co-sponsors ENROLLED HOUSE BILL No. 4135 AN ACT to make appropriations to the department of natural resources; to provide for the acquisition of land; to provide for the development of public recreation facilities; to provide for the powers and duties of certain state agencies and officials; and to provide for the expenditure of appropriations. The People of the State of Michigan enact: Sec. 1. There is appropriated for the department of natural resources to supplement former appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1987, the sum of $15,300,000.00 for land acquisition and $5,100,000.00 for public recreation facility development grants as provided in section 35 of article IX of the state constitution of 1963 and the Michigan natural resources trust fund act, Act No. 101 of the Public Acts of 1985, being sections 318.501 to 318.516 of the Michigan Compiled Laws, from the following funds: GROSS APPROPRIATION.......................................................................................................... $ 20,400,000 Appropriated from: Special revenue funds: Michigan natural resources trust fund......................................................................................... $ 20,400,000 State general fund/general purpose............................................................................................. $ -0- DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES A. Michigan natural resources trust fund land acquisition (by priority) 1. Coldwater Lake farms, phase II, Branch county 2. Herman properties, phase II, Muskegon and Newaygo counties 3. Arends farm, phase II, Muskegon and Newaygo counties 4. -

Designated Trout Lakes and Streams

DESIGNATED TROUT LAKES FO - 200.02 Following is a listing of designated Type A lakes. Type A lakes are managed strictly for trout and, as such, are DESIGNATED TROUT LAKES. County Lake Name Alcona O' Brien Lake Alger Addis Lakes (T46N, R20W, S33) Alger Cole Creek Pond (T46N, R20W, S24) Alger Grand Marais Lake Alger Hike Lake Alger Irwin Lake Alger Rock Lake Alger Rock River Pond Alger Sullivan Lake (T49N, R15W, S21) Alger Trueman Lake Baraga Alberta Pond Baraga Roland Lake Chippewa Dukes Lake Chippewa Highbanks Lake Chippewa Naomikong Lake Chippewa Naomikong Pond Chippewa Roxbury Pond, East Chippewa Roxbury Pond, West Chippewa Trout Brook Pond Crawford Bright Lake Crawford Glory Lake Crawford Kneff Lake Crawford Shupac Lake 1 of 86 DESIGNATED TROUT LAKES County Lake Name Delta Bear Lake Delta Carr Lake (T43N, R18W, S36) Delta Carr Ponds (T43N, R18W, S26) Delta Kilpecker Pond (T43N, R18W, S11) Delta Norway Lake Delta Section 1 Pond Delta Square Lake Delta Wintergreen Lake (T43N, R18W, S36) Delta Zigmaul Pond Gogebic Castle Lake Gogebic Cornelia Lake Gogebic Mishike Lake Gogebic Plymouth Lake Houghton Penegor Lake Iron Deadman’s Lk (T41N, R32W, S5 & 8) Iron Fortune Pond (T43N, R33W, S25) Iron Hannah-Webb Lake Iron Killdeer Lake Iron Madelyn Lake Iron Skyline Lake Iron Spree Lake Isabella Blanchard Pond Keweenaw Manganese Lake Keweenaw No Name Pond (T57N, R31W, S8) Luce Bennett Springs Lake Luce Brockies Pond (T46N, R11W, S1) 2 of 86 DESIGNATED TROUT LAKES County Lake Name Luce Buckies Pond (T46N, R11W, S1) Luce Dairy Lake Luce Dillingham -

T Argetm Arketa Nalysis

T argetM arketAnalysis CharlevoixCounty M ichigan THEM ARKET STRATEGY N ovember3,2014 P reparedfor: P reparedby: Acknowledgements M ichiganS tateHousingDevelopmentAuthority GaryHeidel,ChiefP lacemakingO fficer JamesE.T ischler,AICP ,PCP ,DirectorofComm unityDev. JulieGardner,CommunityDevelopmentS pecialist DianeKarkau,Comm unityDevelopmentS pecialist BryanR obb,StatewideP artnerships/T A S pecialist DavidAllen,PhD,ChiefM arketAnalyst TMA N orthwestM ichiganCouncilofGovernments T eam L arryC.Inman ChairmanoftheBoard S arahL ucas,AICP R egionalPlanner ConsultantT eam S haronM .W oods,M A,CR E P reparedfor: T M A T eamL eader,ProjectM anager P rincipal,LandU se|U S A N athanL ong,PhD T M A Consultant R yanE.Griffith,M A,CFM T M A Consultant P reparedby: Market Strategy Report Page Executive Summary 1 TOC Market Potential 4 Regional Comparisons 13-14 Prepared for: Contact Information 15 Prepared by: NW Michigan Prosperity Region TMA Executive Summary – Charlevoix County Executive Summary This Executive Summary of the Target Market Analysis for Charlevoix County has been prepared as part of a regional study completed for 10 counties comprising the Northwest Michigan Prosperity Region (Region 2). The more complete narrative report begins on page 4 of this report, and includes a more complete explanation of the Place Scores; market potential for both aggressive and conservative scenarios; and housing affordability. The Market Potential and Strategy The Study Areas –There are 11,282 households in Charlevoix County as of month-end June 2014. Of these, 14.7% are located in Boyne City; 11.3% are in Charlevoix; 8.6% are in East Jordan; 2.8% are in Bay Shore; and smaller shares are residing in other small urban places and throughout the surrounding rural areas. -

Walloon Lake Shoreline Survey 2016

Walloon Lake Shoreline Survey 2016 By Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council Report written by: Matt L. Claucherty Monitoring and Research Coordinator Table of Contents Page List of Tables and Figures iii Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 2 Shoreline Development Impacts 2 Study Area 6 Methods 13 Field Survey Parameters 13 Data Processing 15 Results 16 Discussion 22 Recommendations 29 Literature and Data Referenced 32 ii List of Tables Page Table 1. Walloon Lake Watershed land-cover statistics 10 Table 2. Categorization system for Cladophora density 13 Table 3. Cladophora density results 16 Table 4. Greenbelt rating results 18 Table 5. Greenbelt rating results by basin 18 Table 6. Shoreline alteration results 20 Table 7. Shoreline erosion results 20 Table 8. Cladophora density comparisons: 2001 to 2016 23 Table 9. Greenbelt rating comparisons: 2001 to 2016 24 Table 10. Shore survey statistics from Northern Michigan lakes 27 List of Figures Page Figure 1. Map of Walloon Lake and Watershed 8 Figure 2. Chart of phosphorus data from Walloon Lake 11 Figure 3. Chart of trophic status index data from Walloon Lake 11 Figure 4. Cladophora algae density results for Walloon Lake 17 Figure 5. Greenbelt score totals results for Walloon Lake 19 Figure 6. Shoreline erosion severity results for Walloon Lake 21 Figure 7. A typical ornamental shoreline on Walloon Lake 26 Figure 8. Increases in developed and altered shorelines on Walloon Lake 28 iii SUMMARY During the late spring of 2016, the Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council conducted a comprehensive shoreline survey on Walloon Lake as part of an update of the Little Traverse Bay Watershed Protection Plan.