Performing Bach Cantatas with Modern Orchestras: a Modern Conductor's Handbook for Applying Historically Informed Practice to Today's Ensembles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

559288 Bk Wuorinen US

INNER CHAMBERS Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Couperin • Hotteterre • Lully • Marais • Montéclair Les Ordinaires Leela Breithaupt, Traverso Erica Rubis, Viola da gamba David Walker, Theorbo Inner Chambers Inner Chambers Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Introduction préluder sur la flûte traversière (‘The Art of Preluding on Jacques-Martin Hotteterre (1674–1763): Michel Pignolet de Montéclair the Flute’). In the manual, Hotteterre teaches his pupils L’Art de préluder sur la (1667–1737): Musical life at the court of Louis XIV was highly ritualised step by step how to improvise or write a prelude in various flûte traversière (1719) Brunetes anciènes et modernes (1725) and filled with dazzling formal public displays. However, keys, and ends with two preludes composed by the 1 Prelude in D major 4:20 $ Je sens naître en mon coeur 1:56 the Sun King also enjoyed music in his more private author. As one of the king’s employed chamber spheres. This debut album reveals the intimate sound musicians, Hotteterre was well respected both as a flautist François Couperin (1668–1733): Deuxième Concert – Suite (1720) 14:59 world that Louis XIV embraced in his inner chambers at and composer. the Palaces of Versailles and Fontainebleau. The music The French Suite was a very popular musical form Premier Concert (1722) 11:03 % Prélude 1:41 reflects the court’s aesthetic preferences: lavish display of which was typically comprised of several dance 2 Prélude 2:18 ^ Allemande 1:49 ornaments and affluence paired with strict hierarchies, movements including Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, 3 Allemande 1:59 & Courante à l’italienne 1:18 love of allegory, and an affected nostalgia for pastoral life Gavotte, Gigue and Menuet, among others. -

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

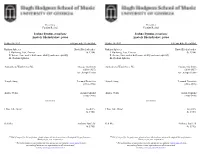

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Introduction

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

Download Booklet

1685 1759 - Violin Sonata in G HWV 358 Violin Sonata in E HWV 373 1 I. [Allegro] 1.57 20 I. Adagio 1.54 2 II. [Adagio] 0.49 21 II. Allegro 2.53 3 III. [Allegro] 2.35 22 III. Largo 1.35 .23 IV Allegro 2.47 Violin Sonata in D minor HWV 359a 4 I. Grave 2.32 Violin Sonata in G minor HWV 368 5 II. Allegro 1.43 24 I. Andante 2.19 6 III. Adagio 0.51 25 II. Allegro 2.49 . 7 IV Allegro 2.35 26 III. Adagio 2.01 .27 IV [Allegro moderato] 2.32 Violin Sonata in A HWV 361 8 I. Andante 2.26 Violin Sonata in F HWV 370 9 II. Allegro 1.54 28 I. Adagio 3.12 10 III. Adagio 0.50 29 II. Allegro 2.13 .11 IV Allegro 2.43 30 III. Largo 3.19 .31 IV Allegro 3.53 Violin Sonata in G minor HWV 364a 12 I. Larghetto 1.56 Violin Sonata in D HWV 371 13 II. Allegro 1.44 32 I. Affettuoso 3.11 14 III. Adagio 0.41 33 II. Allegro 2.57 .15 IV Allegro 2.14 34 III. Larghetto 2.46 .35 IV Allegro 3.55 Violin Sonata in A HWV 372 80.00 16 I. Adagio 1.15 17 II. Allegro 2.24 The Brook Street Band 18 III. Largo 1.14 Rachel Harris baroque violin .19 IV Allegro 2.57 Tatty Theo baroque cello · Carolyn Gibley harpsichord 2 Handel’s Violin Sonatas For a composer as well known as George Frideric Handel, the history of his violin sonatas is somewhat complicated. -

Eubo Mobile Baroque Academy

EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY EUROPEAN CO OPERATION PROJECT 2015 2018 INTERIM REPORT Pathways & Performances CONTENTS EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY........................................2?3 PARTNER ORGANISATIONS ....................................................4?13 INTERNATIONAL CONCERT TOURS ....................................14?18 MUSIC EDUCATION ...............................................................19?22 OTHER ACTIVITIES ................................................................23?25 HOW DO WE MAKE ALL THIS HAPPEN ................................26?27 WHO IS WHO................................................................................28 EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY The EUBO Mobile Baroque Academy (EMBA) co-operation project addresses the unequal provision across the European Union of baroque music education and performance, in new and creative ways. The EMBA project builds on the 30-year successful track-record of the European Union Baroque Orchestra (EUBO) in providing training and performing opportunities for young EU period performance musicians and extends and develops possibilities for orchestral musicians intending to pursue a professional career. From an earlier stage of conservatoire training via orchestral experience, through to the first steps in the professional world, musicians attending the activities of EMBA are offered a pathway into the profession. The EMBA activities supporting the development of emerging musicians include specialist masterclasses by expert tutors; residential orchestral selection -

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

ONYX4106.Pdf

DOMENICO SCARLATTI (1685–1757) Sonatas and transcriptions 1 Scarlatti: Sonata K135 in E 4.03 2 Scarlatti/Tausig: Sonata K12 in G minor 4.14 3 Scarlatti: Sonata K247 in C sharp minor 4.39 4 Scarlatti/Friedman: Gigue K523 in G 2.20 5 Scarlatti: Sonata K466 in F minor 7.25 6 Scarlatti/Tausig: Sonata K487 in C 2.41 7 Scarlatti: Sonata K87 in B minor 4.26 8 Gieseking: Chaconne on a theme by Scarlatti (Sonata K32) 6.43 9 Scarlatti: Sonata K96 in D 3.52 10 Scarlatti/Tausig: Pastorale (Sonata K9) in E minor 3.49 11 Scarlatti: Sonata K70 in B flat 1.42 12 Scarlatti/Friedman: Pastorale K446 in D 5.09 13 Scarlatti: Sonata K380 in E 5.57 14 Scarlatti/Tausig: Sonata K519 in F minor 2.54 15 Scarlatti: Sonata K32 in D minor 2.45 Total timing: 62.40 Joseph Moog piano Domenico Scarlatti’s legacy of 555 sonatas for harpsichord represent a vast treasure trove. His works fascinate through their originality, their seemingly endless richness of invention, their daring harmonics and their visionary use of the most remote tonalities. Today Scarlatti has once again established a firm place in the pianistic repertory. But the question preoccupying me was the influence his music had on the composers of the Romantic era. If we cast an eye over the countless recordings of transcriptions and arrangements of his contemporary Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), it becomes even clearer that in Scarlatti’s case, we find hardly anything comparable. A fascinating process of investigation eventually led me to Carl Tausig (1841–1871), Ignaz Friedman (1882–1948) and Walter Gieseking (1895–1956). -

The Use of Multiple Stops in Works for Solo Violin by Johann Paul Von

THE USE OF MULTIPLE STOPS IN WORKS FOR SOLO VIOLIN BY JOHANN PAUL VON WESTHOFF (1656-1705) AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO GERMAN POLYPHONIC WRITING FOR A SINGLE INSTRUMENT Beixi Gao, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2017 APPROVED: Julia Bushkova, Major Professor Paul Leenhouts, Committee Member Susan Dubois, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Gao, Beixi. The Use of Multiple Stops in Works for Solo Violin by Johann Paul Von Westhoff (1656-1705) and Its Relationship to German Polyphonic Writing for a Single Instrument. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2017, 32 pp., 19 musical examples, bibliography, 46 titles. Johann Paul von Westhoff's (1656-1705) solo violin works, consisting of Suite pour le violon sans basse continue published in 1683 and Six Suites for Violin Solo in 1696, feature extensive use of multiple stops, which represents a German polyphonic style of the seventeenth- century instrumental music. However, the Six Suites had escaped the public's attention for nearly three hundred years until its rediscovery by the musicologist Peter Várnai in the late twentieth century. This project focuses on polyphonic writing featured in the solo violin works by von Westhoff. In order to fully understand the stylistic traits of this less well-known collection, a brief summary of the composer, Johann Paul Westhoff, and an overview of the historical background of his time is included in this document.