Red-Necked Grebes Become Semicolonial When Prime Nesting Substrate Is Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

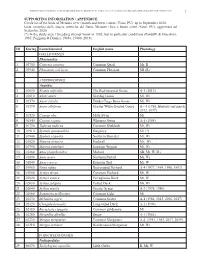

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Aberrant Plumages in Grebes Podicipedidae

André Konter Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae in grebes plumages Aberrant Ferrantia André Konter Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg www.mnhn.lu 72 2015 Ferrantia 72 2015 2015 72 Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le Musée national d’histoire naturelle à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison, aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG parus entre 1981 et 1999. Comité de rédaction: Eric Buttini Guy Colling Edmée Engel Thierry Helminger Mise en page: Romain Bei Design: Thierry Helminger Prix du volume: 15 € Rédaction: Échange: Musée national d’histoire naturelle Exchange MNHN Rédaction Ferrantia c/o Musée national d’histoire naturelle 25, rue Münster 25, rue Münster L-2160 Luxembourg L-2160 Luxembourg Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Fax +352 46 38 48 Fax +352 46 38 48 Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/ Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/exchange email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Page de couverture: 1. Great Crested Grebe, Lake IJssel, Netherlands, April 2002 (PCRcr200303303), photo A. Konter. 2. Red-necked Grebe, Tunkwa Lake, British Columbia, Canada, 2006 (PGRho200501022), photo K. T. Karlson. 3. Great Crested Grebe, Rotterdam-IJsselmonde, Netherlands, August 2006 (PCRcr200602012), photo C. van Rijswik. Citation: André Konter 2015. - Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae - An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide. Ferrantia 72, Musée national d’histoire naturelle, Luxembourg, 206 p. -

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR of the EARED GREBE, Podiceps Caspicus Nigricollis by NANCY MAHONEY Mcallister B.A., Oberlin College, 1954

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR OF THE EARED GREBE, Podiceps caspicus nigricollis by NANCY MAHONEY McALLISTER B.A., Oberlin College, 1954 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OP THE REQUIREMENTS POR THE DEGREE OP MASTER OP ARTS in the Department of Zoology We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OP BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1955 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representative. It is under• stood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 3, Canada. ii ABSTRACT The present study describes and analyses the elements involved in the reproductive behaviour of the Eared Grebe and the relationships between these elements. Two summers of observation and comparison with the published work on the Great Crested Grebe give some insight into these ele• ments, their evolution, and their stimuli. Threat and escape behaviour have been seen in the courtship of many birds, and the threat-escape theory of courtship in general has been derived from these cases. In the two grebes described threat plays a much less important role than the theory prescribes, and may not even be important at all. In the two patterns where the evolutionary relation• ships are clear, the elements are those of comfort preening. -

Great Crested Grebe Podiceps Cristatus in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu

120 Indian BIRDS VOL. 14 NO. 4 (PUBL. 23 OCTOBER 2018) Bristled Grassbird Chaetornis striata: A pair of Grassbirds was George, A., 2018. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S43199767. [Accessed seen on 24 February 2018, photographed [119] on 26 February, on 13 August 2018.] and seen on the subsequent day as well. This adds to the recent George, P. J., 2015. Chestnut-eared Bunting Emberiza fucata from Ezhumaanthuruthu, Kuttanad Wetlands, Kottayam District. Malabar Trogon 13 (1): 34–35. knowledge on its wintering status in Karnataka. Other records Harshith, J. V., 2016. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33278635. are from Dakshin Kannada (Harshith 2016; Kamath 2016; [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Viswanathan 2017), Mysuru (Vijayalakshmi 2016), and Belgaum Kamath, R., 2016. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33148312. [Accessed (Sant 2017). on 13 August 2018.] Lakshmi, V., 2015. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S21432671. [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Monnappa, B., 2012. Website URL: https://www.indianaturewatch.net/displayimage. php?id=317526. [Accessed on 14 August 2018.] Nair. A. 2018. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S43311515. [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Naoroji, R., 2006. Birds of prey of the Indian Subcontinent. Reprint ed. New Delhi: Om Books International. Pp. 1–692. Narasimhan, S. V., 2004. Feathered jewels of Coorg. 1st ed. Madikeri, India: Coorg Wildlife Society. Pp. 1–192. Orta, J., Boesman, P., Marks, J. S., Garcia, E. F. J., & Kirwan, G. M., 2018. Western Marsh- harrier (Circus aeruginosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., & de Juana, E., (eds.). -

Distribution and Foraging Behaviour of Wintering Western Grebes

DISTRIBUTION AND FORAGING BEHAVIOUR OF WINTERING WESTERN GREBES by James S. Clowater BSc., University of Victoria, 1993 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Biological Sciences O James S. Clowater 1998 SMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 1998 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Bibliothèque nationale (*m of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your filo Vorre réfirence Our file Nofie refdrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disûibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenivise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pemission. autorisation. The Western Grebe, Aechmophorus occidentalis, is a species which breeds mainly in the prairie regions of Canada and the United States and winters on the Pacific Coast. -

33. the Courtship Habits of the Great Crested Grrebe (Podiceps

PROCEEDINGS OF TlIE GENERAL MEETINGS FOR SCIENTIFIC BUS ESS OF TIlfi ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON. PAPERS. 33. The Courtship - habits * of the Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps c~istatus); with an addition to the Theory of Sexual Selection. By JULXANS. HUXLEY,B.A., Professor of Biology in the ltice Iiistitute, Houston, Texas t. [Received March 14, 1914: Read April 21,19141 (Plates: I. & 11.:) INDEX. I. GENERALPART. Page 1. Introduction ......................................................... 492 2. Appearance. ............ ............................................. ... 492 3. Annual History ...................................................... 495 4. Some Descriptions ................................................... 496 5. The Itelations of the Sexes. (i.) The act of pairing .......................................... 60 1 (ii.) Courtship ................................................... 608 (iii.) Nest-building ...................................... 617 (iv.) Relations of ditferent pairs .................... 521 (v.) Other activities ..................................... 622 6. Discussion ................................................... 622 __- _______ X It was not until this paper was in print that I realized that the word Courtship is perliaps mislending ax applied to the incidents here recorded. While Courtship s-d, strictly speaking, denote only ants-nuptial hehavionr, it may readily be extended to include any behaviour by which an orga!iism of one sex seeks to “ win over’’ one of the opposite sen. will be seen that the behaviour of the Grebe cannot be included under this. Love-habitas” would bo a better term in snme ~ayli;for the present, however, it is sufficient to point out the inadequacy of the present biological terminology. t Conimnnicated hy the SECRETARY. z For enplanntion of the PlateR see 1). 561. PHOC.ZOOL. S0C.-1914, NO.YYXV. 35 4!)5 3111. d. s. III:xLIsY ox TIIE 11. sl-IKI.\l>T’AIlT. 7. I,ocalit~,iiietliods, rtc. -

Critter Class Grebe

Critter Class Grebe Animal Diversity Web - Pied bill grebe September 21, 2011 Here is a link to the bird we will discuss tonight http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1XAFo_uVgk MVK: We will discuss the Glebe but we can have fun too! LOL MVK: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdxxZgxWPt8 Comment: Oh my, how beautiful that was. Comment: Beautiful birds, they can even walk on water!! Comment: So cool how they walk on water! Comment: What an interesting bird and dance! Comment: Hi MVK...Neat bird...quite the courtship. MVK: There are 22 species of the grebe - so not all are the beautiful black and white ones in the videos. They are the Clark's grebe. MVK: The BBC does some beautiful animal documentaries - they also do the Lily and Hope Black Bear series. Comment: Where are they found (besides Oregon!)? MVK: Well it isn't letting me save the range map. Critter Class – Grebe 1 9/21/2011 MVK: A grebe ( /ˈɡriːb/) is a member of the Podicipediformes order, a widely distributed order of freshwater diving birds, some of which visit the sea when migrating and in winter. This order contains only a single family, the Podicipedidae, containing 22 species in 6 extant genera. Per Wikipedia MVK: Becky - there are many different types of grebes. The pied bill grebe is found pretty much in all the US Comment: Beautiful and graceful birds! I've never senn one before. Anxious to learn! MVK: Grebes are small to medium-large in size, have lobed toes, and are excellent swimmers and divers. -

Full Article

NOTORNIS QUARTERLY JOURNAL of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand flncorporatedl Volume Eighteen, Number One, March, 1971 NOTORNIS In continuation of New Zealand Bird Notes Volume XVIII, No. 1 MARCH, 1971 JOURNAL OF THE ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND (Incorporated) Registered with the G.P.O., Wellington, as a Magazine Edited by R. B. SIBSON, 26 Entrican Avenue, Remuera, Auckland 5 Annual Subscription: Student Membership, $2 (to age 18) ; Ordinary Membership, $4; Endowment Membership, $5; Husband/Wife Membership, $5; Life Membership, $80 (age over 30). Subscriptions are payable on a calendar year basis at the time of application for membership and on receipt of invoice each January thereafter. Applications for Membership, Changes of address and Letters of Resignation should he forwarded to the Hon. Treasurer. OFFICERS 1970 - 71 President - Dr. G. R. WILLIAMS, Wildlife Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Private Bag, Wellington Vice-president - Mr. F. C. KINSKY, Dominion Museum, Wellington Editor - Mr. R. B. SIBSON, 26 Entrican Avenue, Auckland, 5 Assistant Editor - Mr. A. BLACKBURN, 10 Score Road, Gisborne Treasurer - Mr. J. P. C. WATT, P.O. Box 1168, Dunedin Secretary - Mr. B. A. ELLIS, 44 Braithwaite Street, Wellington, 5 Members of Council: Mr. B. D. BELL, Wildlife Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Wellington Mr. A. BLACKBURN, 10 Score Road, Gisborne Dr. P. C. BULL, 131 Waterloo Road, Lower Hutt Dr. R. A. FALLA, 41 Kotari Road, Days Bay, Wellington Mrs. J. B. HAMEL, 42 Ann Street, Roslyn, Dunedin Mr. N. B. MACKENZIE, Paltowai, Napier R.D. 3 Mr. R. R. SUTTON, Lorneville Post Office, Invercargill Conveners and Organisers: Nest Records: Mr. -

The Pair-Formation Displays of the Western Grebe

THE CONDOR JOURNAL OF THE COOPER ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY Volume 84 Number 4 November 1982 Condor &X135&369 0 The CooperOmithological Society1982 THE PAIR-FORMATION DISPLAYS OF THE WESTERN GREBE GARY L. NUECHTERLEIN AND ROBERT W. STORER ABSTRACT. -In this paper we describeand illustrate the pair-formation displays of the Western Grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis),examining their structural variation, social contexts, and probable evolutionary origins and functions. Most displaysare performed mutually by two or more individuals and occur in elaborate and predictable sequencesor “ceremonies.” One of these, the “Rushing Cere- mony” is performed by either two males, a male and a female, or several males and a female. The “Weed Ceremony,” on the other hand, occurs later in the pairing sequenceand always involves a male and a female. Finally, the “Greeting Ceremony,” used by pairs coming together after being separated, appears to be an abbreviation of the above two ceremonieswith the energetic, core displays left out. We examine the temporal and spatial coordination between individuals involved in each of these ceremonies. Most displays and ceremonies of Western Grebes differ greatly from those described for other grebe species, which supports morphological evidence for retaining the Western Grebe in a separate genus. The similarity of the Weed Ceremony to that of some speciesof Podicepssupports morphological evidence for consideringthe Western Grebe more closely related to that genusthan to any other. The spectacular courtship displays of the description of a typical performance is fol- Western Grebe (Aechmophorusoccidentalis) lowed by comments on variability from one have aroused considerable attention, yet, sur- performance to the next, the degreeand nature prisingly, no detailed description of them has of coordination and orientation among dis- been published. -

Observation on the Great Grebe

July, 1963 279 OBSERVATIONS ON THE GREAT GREBE By ROBERTW. STORER The Great Grebe or Huala (Podiceps majm) is widely distributed in temperate South America from southern Brazil to Tierra de1 Fuego. A major center of abundance is in the lake districts of southern Argentina and southern Chile. The observations on which this report is based were made iby Frank B. Gill and me near Llifen on the east shore of Lake Ranco, Valdivia Province, Chile. Here we were the guests of A. W. Johnson, who kindly permitted us to use his fishing lodge, “Quinta Chucao,” and who in many other ways helped us in our work. We are also indebted to Mr. and Mrs. M. Hadida for their hospitality and for accessto their property, from which most of the observations were made. La Poza is a deep, nearly land-locked cove approximately three miles south of Llifen. Its southwest shore is formed by the delta of the Rio Milahue, one of four major streams of Andean origin which empty into Lake Ranco. Small areas of reeds (S&pus) and brush grow in the shallow water at the edge of the delta, and in these a colony of 25 to 30 pairs of Great Grebes had started building nests by October 5, 1961. The nests were still unfinished and no eggs were found on the date of our last visit to La Poza on October 16. Almost without exception our observations were made from a sandy point marking the northern shore of the narrows separating La Poza from Lake Ranco. -

Nest Site Selection by Eared Grebes in Minnesota’

The Condor 96: 19-35 8 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1994 NEST SITE SELECTION BY EARED GREBES IN MINNESOTA’ JANET S. BOE* Department of Zoology, North Dakota State University,Fargo, ND 58105 Abstract. This study examined nest site selection within Eared Grebe (Podicepsnigri- collis) colonies in terms of nesting synchrony, nearest-neighbordistances, vegetation, ex- posure,and nest success.Nests in 11 Eared Grebe coloniesin Minnesota were initiated over a span of 1 l-45 days, with most nests in each colony initiated in < 11 days. In each of six colonies studied, mean nearest-neighbordistance of the earliest nestswas greater than that of the complete colony. Nearest-neighbor distance tended to decreasewith an increase in emergent vegetation density. Early nests seemed to form the skeleton of a neighborhood, with later nests filling in or establishingother neighborhoods.In five of six colonies, clutch sizes were larger in earlier nests. No significantdifference in egg volume between early and late nests was apparent in the two colonies studied. Early nests were more successfulthan were late nests in two of four colonies; center nests were more successfulthan were edge nestsat only one of four colonies. Most nest destructionin this study was causedby waves generatedby high winds; ~2% of nests showed evidence of predation. Key words: Eared Grebe;Podiceps nigricollis; Podicipediformes;habitat selection:nest- site selection;nesting synchrony. - INTRODUCTION result in rapidly changing vegetation patterns, Selection of a breeding habitat that meets the which probably contribute to the peripatetic na- reproductive requirements of an animal is crit- ture of grebe colony formation (Cramp and Sim- ical to its evolutionary fitness (Partridge 1978).