Caerwys Town Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspectors Report

The Planning Inspecto rate Report to the Secretary of Temple Quay House 2 The Square Temple Quay State for Transport Bristol BS1 6PN GTN 1371 8000 by A MEAD BSc(Hons) MRTPI MIQ an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Transport Date: 28 March 2006 HARBOURS ACT 1964 Harbour Revision Orders Promoted by (A) Environment Agency (Wales) at the Dee Estuary & (B) Mostyn Docks Ltd at Mostyn Harbour Inquiry held on 29th – 30th November; 1st ,6th , 8th December 2005 File Ref: DPI/17/32 /LI A6835 2 Order A File Ref: DPI/17/32 /LI A6835 The Dee Estuary The Order would be made under Section 14 of the Harbours Act 1964 The promoter is the Environment Agency (EA) The Order would facilitate the implementation of the Port Marine Safety Code, modernise the Agency’s conservancy functions and enable ships dues to be collected [see paras 5.53 – 5.61 below]. The number of objectors at the close of the inquiry was four. Summary of Recommendation: To confirm subject to amendments as proposed by the EA. Order B File Ref: DPI/17/32 /LI A6835 Mostyn Harbour, Flintshire The Order would be made under Section 14 of the Harbours Act 1964 The promoter is Mostyn Docks Limited (Mostyn) The Order would facilitate the implementation of the Port Marine Safety Code and extend the powers of Mostyn in respect of Aids to Navigation, wreck removal and pilotage jurisdiction. The number of objectors at the close of the inquiry was six. Summary of Recommendation: To confirm, but only so far as pilotage is concerned. -

Pte. James David Dallow 11Th South Wales Borderers

Newbridge War Memorial Pte. James David Dallow 11th South Wales Borderers www.newbridgewarmemorial.co.uk Newbridge War Memorial Pte. James David Dallow 11th South Wales Borderers Commemorated on Newbridge War Memorial as J. Dallow SWB Commemorated on Celynen Collieries Roll of Honour Family James David Dallow was born in 1895, the son of Charles and Margaret Dallow. The 1901 Census show six year old James to be the second of four children - Annie E Dallow (7) was born a year before him and he had younger siblings William C Dallow (4) and Mary S M Dallow (2). Charles was originally from Hereford and Margaret from Crickhowell, all the children were born in Abercarn. In 1911 the family were living at 42 Celynen Terrace in Newbridge. Charles and his two sons were all working as coal hewers in a local colliery whilst Mary was still at school. The family appear to have had a further son, Thomas, although the Census shows him as having died. The family had a lodger called John Knight who also worked at the colliery but was a boiler stoker working above ground. Military James David Dallow enlisted in the army and was posted as Private 23247 to the 11th Battalion of the South Wales Borderers, part of the 115th Brigade of the 38th (Welsh) Division. In December 1915 the 38th (Welsh) Division embarked for France, the 11th Battalion arriving at Le Havre on 4th December 1915. The following is an extract from a factsheet issued by the South Wales Borderers Museum, Brecon After spells in the Line at Givenchy in the spring of 1916 the Division moved to the River Ancre on 3rd July at the opening of the Battle of the Somme, and both battalions had their first real action in the attack on Mametz Wood. -

Pharmacies Providing Patient Sharps Boxes Exchange Service - As at April 2015

Pharmacies Providing Patient Sharps Boxes Exchange Service - as at April 2015 WEST Pharmacy Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 County Post Code S B Carr Ltd London Road Valley Anglesey LL65 3DP Rowlands Amlwch Primary Care Centre Parys Road Amlwch Anglesey LL68 9AB Rowlands 17 Castle Street Beumaris Anglesey LL58 8AP Rowlands Tyn-Y-Gongl Benllech Bay Anglesey LL74 8TG Rowlands Medical Hall Cemaes Bay Anglesey LL67 0HH Rowlands 62 Market Street Holyhead Anglesey LL65 1UN Rowlands Holyhead Road Llanfair PG Anglesey LL61 5UJ Rowlands 1 High Street Llangefni Anglesey LL77 7LT Rowlands Gormer Builders Yard Coronation Road Menai Bridge Anglesey LL59 5BD Boots Queens Square Dolgellau Gwynedd LL40 1AL Boots 277 - 279 High Street Bangor Gwynedd LL57 1PA Boots Ye Hen Orsaf Medical Centre Station Road Bethesda Gwynedd LL57 3NE Boots 1 - 3 Pool Lane Caernarfon Gwynedd LL55 2AL Penygroes Pharamcy 37 Water Street Penygroes Gwynedd LL54 6LR Mr Andrew Martin D Powys Davies 26 High Street Blaenau Ffestiniog Gwynedd LL41 3AA Rowlands High Street Abersoch Gwynedd LL53 7DY Rowlands 42 High Street Bala Gwynedd LL23 7AB Rowlands Bron Derw Glynne Road Bangor Gwynedd LL57 1AH Rowlands 29 Holyhead Road Bangor Gwynedd LL57 2EU Rowlands Cors Y Gedol high Street Barmouth Gwynedd LL42 1DP Rowlands 3 Eldon Row Dolgellau Gwynedd LL40 1PS Rowlands Medical Hall Harlech Gwynedd LL46 2YA Rowlands Compton House Llanberis Gwynedd LL55 4EU Rowlands Castle Street Penrhyndeudraeth Gwynedd LL48 6AL Rowlands 127 High Street Porthmadog Gwynedd LL49 9HA Rowlands The Old Post Office -

Thomas Edward Ellis Papers (GB 0210 TELLIS)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Thomas Edward Ellis Papers (GB 0210 TELLIS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/thomas-edward-ellis-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/thomas-edward-ellis-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Thomas Edward Ellis Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 4 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Pwyntiau -

97 Winter 2017–18 3 Liberal History News Winter 2017–18

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 97 / Winter 2017–18 / £7.50 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y The Forbidden Ground Tony Little Gladstone and the Contagious Diseases Acts J. Graham Jones Lord Geraint of Ponterwyd Biography of Geraint Howells Susanne Stoddart Domesticity and the New Liberalism in the Edwardian press Douglas Oliver Liberals in local government 1967–2017 Meeting report Alistair J. Reid; Tudor Jones Liberalism Reviews of books by Michael Freeden amd Edward Fawcett Liberal Democrat History Group “David Laws has written what deserves to become the definitive account of the 2010–15 coalition government. It is also a cracking good read: fast-paced, insightful and a must for all those interested in British politics.” PADDY ASHDOWN COALITION DIARIES 2012–2015 BY DAVID LAWS Frank, acerbic, sometimes shocking and often funny, Coalition Diaries chronicles the historic Liberal Democrat–Conservative coalition government through the eyes of someone at the heart of the action. It offers extraordinary pen portraits of all the personalities involved, and candid insider insight into one of the most fascinating periods of recent British political history. 560pp hardback, £25 To buy Coalition Diaries from our website at the special price of £20, please enter promo code “JLH2” www.bitebackpublishing.com Journal of Liberal History advert.indd 1 16/11/2017 12:31 Journal of Liberal History Issue 97: Winter 2017–18 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Liberal history news 4 Editor: Duncan Brack Obituary of Bill Pitt; events at Gladstone’s Library Deputy Editors: Mia Hadfield-Spoor, Tom Kiehl Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Archive Sources Editor: Dr J. -

Hydrogeology of Wales

Hydrogeology of Wales N S Robins and J Davies Contributors D A Jones, Natural Resources Wales and G Farr, British Geological Survey This report was compiled from articles published in Earthwise on 11 February 2016 http://earthwise.bgs.ac.uk/index.php/Category:Hydrogeology_of_Wales BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2015. Hydrogeology of Wales Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290 EUL. N S Robins and J Davies Bibliographical reference Contributors ROBINS N S, DAVIES, J. 2015. D A Jones, Natural Rsources Wales and Hydrogeology of Wales. British G Farr, British Geological Survey Geological Survey Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. Cover photo: Llandberis Slate Quarry, P802416 © NERC 2015. All rights reserved KEYWORTH, NOTTINGHAM BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 2015 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS British Geological Survey offices shops at Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or BGS Central Enquiries Desk shop online at www.geologyshop.com Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 email [email protected] The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including Environmental Science Centre, Keyworth, maps, for consultation. -

£250,000 Halfryn, Berllan Lane, Gwespyr, Holywell, CH8

COUNCIL TAX BAND Tax band E TENURE Freehold LOCAL AUTHORITY Flintshire County Council DATE: 22nd August 2017 OFFICE T: 01745 888100 19 Meliden Road E: [email protected] Prestatyn W: www.peterlarge.com Halfryn, Berllan Lane, Gwespyr, Holywell, CH8 9LF £250,000 Denbighshire LL19 9SD CONSUMER PROTECTION REGULATIONS 2008 AND THE BUSINESS PROT ECTION FROM MISLEADING MARKETING REGULATIONS 2008 • DETACHED DOUBLE FRONTED • THREE RECEPTION ROOMS These particulars, whilst beli eved to be accurate, are set out for guidance only and do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. Prospecti ve purchasers or tenants should not rel y on these particul ars as statement or representation of fact, but must satisfy themsel ves by inspection or otherwise as to their accuracy. No person in the employment of PET ER LARGE Estate Agents has the author ity to make or give any representation or warranty in relation to the property. Room sizes are approximate and all comments are of the opinion of PETER LARGE Estate Agents having carried out a wal k through • TWO BEDROOMS • FITTED KITCHEN inspecti on. T hese sal es particulars ar e prepared under the consumer protection regulati ons 2008 and are governed by the business protection from misleading mar keting regulations 2008. BEDROOM TWO SERVICES 14' 4" x 10' 8" (4.38m x 3.27m) With far reaching Mains electricity are believed available or coastal views, double panelled radiator, power connected to the property with private drainage points, two double fitted wardrobes, top box and central heating by way of oil. All services and storage cupboards and knee hole mirror back appliances not tested by the Selling Agent. -

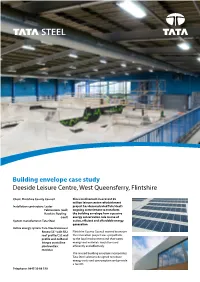

Building Envelope Case Study Deeside Leisure Centre, West Queensferry, Flintshire

Building envelope case study Deeside Leisure Centre, West Queensferry, Flintshire Client: Flintshire County Council Close involvement in a recent £5 million leisure centre refurbishment Installation contractors: Lester project has demonstrated Tata Steel’s Fabrications (wall) ongoing commitment to transform Hawkins Roofing the building envelope from a passive (roof) energy conservation role to one of System manufacturer: Tata Steel active, efficient and affordable energy generation. Active energy system: Tata Steel Colorcoat Renew SC® with R32 Flintshire County Council wanted to ensure roof profile/C32 wall the renovation project was sympathetic profile and SolBond to the local environment and that water, Integra crystalline energy and materials would be used photovoltaic efficiently and effectively. modules The revised building envelope incorporates Tata Steel solutions designed to reduce energy costs and consumption and provide a facelift. Telephone: 0845 30 88 330 Building envelope case study Deeside Leisure Centre, West Queensferry, Flintshire Close involvement in a recent £5 million leisure centre refurbishment project has demonstrated Tata Steel’s ongoing commitment to transform the building envelope from a passive energy conservation role to one of active, efficient and affordable energy generation. Deeside Leisure Centre, West Queensferry, Flintshire, is the National Centre for Ice Sports in Wales. It boasts an Olympic size ice pad, skatepark and spa. Other facilities include a fitness suite, 3G football pitches, 8-court sports hall and squash courts. Flintshire County Council wanted to ensure the renovation project was sympathetic to the local environment and that water, energy and materials would be used efficiently and effectively. Colorcoat Renew SC® is an active solar air SOLbond Integra crystalline photovoltaic The revised building envelope incorporates heating system, with a pre-engineered modules are bonded directly to R32. -

The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales

Volume 3 │ Issue 1 │ 2018 The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales McKinley Terry Abilene Christian University Texas Psi Chapter Vol. 3(1), 2018 Article Title: The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales DOI: 10.21081/AX0173 ISSN: 2381-800X Key Words: Wales, poets, 20th Century, World War I, memorials, bards This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Author contact information is available from the Editor at [email protected]. Aletheia—The Alpha Chi Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship • This publication is an online, peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary undergraduate journal, whose mission is to promote high quality research and scholarship among undergraduates by showcasing exemplary work. • Submissions can be in any basic or applied field of study, including the physical and life sciences, the social sciences, the humanities, education, engineering, and the arts. • Publication in Aletheia will recognize students who excel academically and foster mentor/mentee relationships between faculty and students. • In keeping with the strong tradition of student involvement in all levels of Alpha Chi, the journal will also provide a forum for students to become actively involved in the writing, peer review, and publication process. • More information and instructions for authors is available under the publications tab at www.AlphaChiHonor.org. Questions to the editor may be directed to [email protected]. Alpha Chi is a national college honor society that admits students from all academic disciplines, with membership limited to the top 10 percent of an institution’s juniors, seniors, and graduate students. -

Rhosesmor & Halkyn

Flintshire Local Development Plan RHOSESMOR - SETTLEMENT SERVICE AUDIT Settlement Commentary Rhosesmor is a small village on Halkyn Mountain with a long lead mining history and there are natural and man-made tunnels under the village which relate to this. There are Sites of Special Scientific Interest and Special Areas of Conservation to the SE and NW of the village, and several Listed Buildings and Buildings of Local Interest (BLI’s) in, or in close proximity to, the village, with a Scheduled Ancient Monument to the NW of the village. There is a small industrial estate at the southern end of the village which provides some employment opportunities. Settlement No. of Dwellings 2000 UDP Baseline Figure 145 2014 Housing Land Study 163 Settlement Population 2001 Census 693 2011 Census 720 Summary of Recorded Service Provision The survey work was undertaken in November 2014 and has since been updated to take account of new information or feedback from Members / Town and Community Councils. Education Indoor No Library Mobile Library Facilities leisure Service, Pre-School / Ysgol Rhos centre / Outside Bryn y Nursery Helyg sports facility Foel Tues Provision Swimming No 10.35- Primary Ysgol Rhos pool 11.05am and school Helyg Formal No Llys Enfys Tues outdoor 11.10 – 12.10 Secondary No sports facility once / twice school Formal Yes, Play area month (varies) College No outdoor play / playing field facility /area Hospital No Other No Education Community & Health Doctors No Facility Community Yes, Village surgery centre / hall Hall Dentist No Leisure -

40Th Sioe Amaethyddol Blynyddol CAERWYS Annual Agricultural Show

R Rhestr dosbarthiadau / Schedule of Classes 40th Sioe Amaethyddol Blynyddol CAERWYS Annual Agricultural Show Dydd Sadwrn / Saturday 13th Mehefin / June 2020 Ty Ucha Farm Caerwys Treffynnon / Holywell Sir Fflint / Flintshire CH7 5BQ CPH: 56 / 204 / 8000 Drwy garedigrwydd / By kind permission of Mr E & Mrs N Thomas Llywydd / President Mr Roger Morris Islywydd / Vice President Mr Tom Stephenson Website: www.Caerwys-Show.org.uk A Message from the President It is a great honour to be elected President of the Fortieth Caerwys Agricultural Show. I would like to pay tribute to the founder members for their inspiration and enterprise in launching the show back in the nineteen seventies. I would like to thank all the past and present members of the Show Committee for all their hard work, commitment and dedication along the way. Not forgetting all our old friends who are very sadly no longer with us. The contribution of all our other staunch supporters from near and far; who have worked tirelessly and contributed in so many different way over the last forty years in order to keep the show going, especially during the more challenging times, is also very much appreciated. That includes all our volunteer helpers for their invaluable labour, the stall holders, entertainers, exhibitors, judges, stewards and the charitable organisations who work, in conjunction with the committee, to stage the show. Staging the show also involves a major financial outlay that would be totally impossible without the generous support of all our many sponsors, for which we are extremely grateful. Caerwys is a traditional Agricultural Show, which provides an interesting day out for everybody from all walks of life, with something for all age groups, from children to senior citizens. -

Jane Hutt: Businesses That Have Received Welsh Government Grants During 2011/12

Jane Hutt: Businesses that have received Welsh Government grants during 2011/12 1 STOP FINANCIAL SERVICES 100 PERCENT EFFECTIVE TRAINING 1MTB1 1ST CHOICE TRANSPORT LTD 2 WOODS 30 MINUTE WORKOUT LTD 3D HAIR AND BEAUTY LTD 4A GREENHOUSE COM LTD 4MAT TRAINING 4WARD DEVELOPMENT LTD 5 STAR AUTOS 5C SERVICES LTD 75 POINT 3 LTD A AND R ELECTRICAL WALES LTD A JEFFERY BUILDING CONTRACTOR A & B AIR SYSTEMS LTD A & N MEDIA FINANCE SERVICES LTD A A ELECTRICAL A A INTERNATIONAL LTD A AND E G JONES A AND E THERAPY A AND G SERVICES A AND P VEHICLE SERVICES A AND S MOTOR REPAIRS A AND T JONES A B CARDINAL PACKAGING LTD A BRADLEY & SONS A CUSHLEY HEATING SERVICES A CUT ABOVE A FOULKES & PARTNERS A GIDDINGS A H PLANT HIRE LTD A HARRIES BUILDING SERVICES LTD A HIER PLUMBING AND HEATING A I SUMNER A J ACCESS PLATFORMS LTD A J RENTALS LIMITED A J WALTERS AVIATION LTD A M EVANS A M GWYNNE A MCLAY AND COMPANY LIMITED A P HUGHES LANDSCAPING A P PATEL A PARRY CONSTRUCTION CO LTD A PLUS TRAINING & BUSINES SERVICES A R ELECTRICAL TRAINING CENTRE A R GIBSON PAINTING AND DEC SERVS A R T RHYMNEY LTD A S DISTRIBUTION SERVICES LTD A THOMAS A W JONES BUILDING CONTRACTORS A W RENEWABLES LTD A WILLIAMS A1 CARE SERVICES A1 CEILINGS A1 SAFE & SECURE A19 SKILLS A40 GARAGE A4E LTD AA & MG WOZENCRAFT AAA TRAINING CO LTD AABSOLUTELY LUSH HAIR STUDIO AB INTERNET LTD ABB LTD ABER GLAZIERS LTD ABERAVON ICC ABERDARE FORD ABERGAVENNY FINE FOODS LTD ABINGDON FLOORING LTD ABLE LIFTING GEAR SWANSEA LTD ABLE OFFICE FURNITURE LTD ABLEWORLD UK LTD ABM CATERING FOR LEISURE LTD ABOUT TRAINING