FLAME SHELL BEDS Image Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Lights Radio Aids and Fog Signals 2011

PUB. 114 LIST OF LIGHTS RADIO AIDS AND FOG SIGNALS 2011 BRITISH ISLES, ENGLISH CHANNEL AND NORTH SEA IMPORTANT THIS PUBLICATION SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE NOTICE TO MARINERS Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Bethesda, MD © COPYRIGHT 2011 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. *7642014007536* NSN 7642014007536 NGA REF. NO. LLPUB114 LIST OF LIGHTS LIMITS NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY PREFACE The 2011 edition of Pub. 114, List of Lights, Radio Aids and Fog Signals for the British Isles, English Channel and North Sea, cancels the previous edition of Pub. 114. This edition contains information available to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) up to 2 April 2011, including Notice to Mariners No. 14 of 2011. A summary of corrections subsequent to the above date will be in Section II of the Notice to Mariners which announced the issuance of this publication. In the interval between new editions, corrective information affecting this publication will be published in the Notice to Mariners and must be applied in order to keep this publication current. Nothing in the manner of presentation of information in this publication or in the arrangement of material implies endorsement or acceptance by NGA in matters affecting the status and boundaries of States and Territories. RECORD OF CORRECTIONS PUBLISHED IN WEEKLY NOTICE TO MARINERS NOTICE TO MARINERS YEAR 2011 YEAR 2012 1........ 14........ 27........ 40........ 1........ 14........ 27........ 40........ 2........ 15........ 28........ 41........ 2........ 15........ 28........ 41........ 3........ 16........ 29........ 42........ 3........ 16........ 29........ 42........ 4....... -

A5.434 Limaria Hians Beds in Tide-Swept Sublittoral Muddy Mixed Sediment

European Red List of Habitats - Marine Habitat Group A5.434 Limaria hians beds in tide-swept sublittoral muddy mixed sediment Summary The flame or gaping file shell Limaria hians creates nests by weaving together tough threads (byssus) with surrounding material such as seaweed, maerl, shells and detritus. Adjoining nests coalesce to form larger structures often with considerable numbers of flame shells buried within them. In some locations, where conditions allow, contiguous flame shell nests can carpet the bed for several hectares. The carpets create a unique habitat that stabilises the sediment and provides an attachment surface for many organisms including hydroids, bryozoans, ascidians and seaweeds. Flame shell beds are highly vulnerable to seabed trawling and dredging together with other activities which abrade the seabed. There have been few studies on their resilience but they are believed to have a low recoverability when all nest material is removed. Other pressures include smothering, change in hydrological conditions and poor water quality. The control and management of the use of trawls and dredges for demersal fishing is the main measure required for the protection and maintenance of this habitat. In addition, local statutory or voluntary controls on water quality, such as prevention of discharges of contaminated water or the regulation of activities that causes increased turbidity and siltation. Synthesis This habitat has a restricted distribution in the North East Atlantic Region, with current known records confined to the west coast of Scotland and one sea lough in Ireland. There are no long term (>50 year) data sets, but more recent studies show that several known beds in Scotland have declined in extent and density of L. -

Contribution of Existing Protected Areas of Identification of Remaining MPA Search Features Priorities Pdf, 1.40MB

FINAL REPORT Contribution of existing protected areas to the MPA network and identification of remaining MPA search feature priorities For further information on this report please contact: Morven Carruthers Oliver Crawford-Avis Scottish Natural Heritage Joint Nature Conservation Committee Great Glen House Inverdee House Leachkin Road Baxter Street Inverness, IV3 8NW Aberdeen, AB11 9QA Telephone: 01463 725 018 Telephone: 01224 266587 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Carruthers, M., Chaniotis, P.D., Clark, L., Crawford-Avis, O., Gillham, K., Linwood, M., Oates, J., Steel, L., and Wilson, E. 2011. Contribution of existing protected areas to the MPA network and identification of remaining MPA search feature priorities. Internal report produced by Scottish Natural Heritage, the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and Marine Scotland for the Scottish Marine Protected Areas Project. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. This report was produced as part of the Scottish MPA Project and the views expressed by the author(s) should not be taken as the views and policies of the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Scottish Natural Heritage or Scottish Ministers. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Detailed assessments were completed for each of the MPA search features, based on the data available in GeMS1. These were used as a basis to assess the extent to which MPA search features are represented within the existing network of protected areas. 130 protected areas (including marine SACs, SPA extensions, SSSIs with maritime components, and fisheries areas established for nature conservation purposes) were included in the analysis. -

Stromeferry Appraisal

Stromeferry Appraisal DMRB Stage 2 Report Volume 2 – Environment Assessment (Final Draft) September 2014 Prepared for: The Highland Council UNITED KINGDOM & IRELAND The Highland Council: DMRB Stage 2 Report, Volume 2 REVISION SCHEDULE Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 1 May 2014 Draft Report Seán Fallon Nigel Hackett Nigel Hackett Senior Planner Technical Technical Director Director 2 September Final Draft Report John Bacon Seán Fallon 2014 Assistant Senior Planner Environmental Consultant John Devenny Senior Landscape Architect Graeme Hull Senior Ecologist Peter Morgan Associate Geology & Soils Gareth Hodgkiss Senior Air Quality Consultant Dan Atkinson Principal Noise Consultant Laura Garcia Senior Heritage Consultant Sally Homoncik Assistant Hydrologist Jill Irving Senior Engineer URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited 2nd Floor, Apex 2, 97 Haymarket Terrace Edinburgh EH12 5HD Tel +44 (0) 131 347 1100 Fax +44 (0) 131 347 1101 www.urs.com DMRB STAGE 2 OPTIONS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REPORT (FINAL DRAFT) September 2014 i The Highland Council: DMRB Stage 2 Report, Volume 2 Limitations URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“URS”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of The Highland Council (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed for the Stromeferry Options Appraisal (URS job number 47065291). No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS. This Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client nor relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. -

Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Post-2020: a Statement of Intent

Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Post-2020: A Statement of Intent December 2020 INTRODUCTION have to change how we interact with and care for nature. The world faces the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. Globally, The twin global crises of biodiversity loss nationally and locally an enormous effort and climate change require us to work is needed to tackle these closely linked with nature to secure a healthier planet. issues. As we move from the United Our Climate Change Plan update outlines Nations Decade on Biodiversity to the new, boosted and accelerated policies, beginning of the United Nations Decade putting us on a pathway to our ambitious of Ecosystem Restoration, with climate change targets and to deliver a preparations being made for the range of co-benefits including for Convention on Biological Diversity’s biodiversity. The way we use land and Conference of the Parties 15 to be held in sea has to simultaneously enable the 2021, this is an appropriate time to reflect transition to net zero as part of a green and set out our broad intentions on how economic recovery, adapt to a changing we will approach the development of a climate and improve the state of nature. new post-2020 Scottish Biodiversity This is an unprecedented tripartite Strategy. challenge. The new UN Decade signals the massive The devastating impact of COVID-19 has effort needed and it is highlighted our need to be far more resilient to pandemics and other ‘shocks’ “…a rallying call for the protection which may arise from degraded nature. and revival of ecosystems around Our Programme for Government and the world, for the benefit of people Climate Change Plan update set out and nature… Only with healthy steps we will take to support a green ecosystems can we enhance recovery. -

HORSE MUSSEL BEDS Image Map

PRIORITY MARINE FEATURE (PMF) - FISHERIES MANAGEMENT REVIEW Feature HORSE MUSSEL BEDS Image Map Image: Rob Cook Description Characteristics - Horse mussels (Modiolus modiolus) may occur as isolated individuals or aggregated into beds in the form of scattered clumps, thin layers or dense raised hummocks or mounds, with densities reaching up to 400 individuals per m2 (Lindenbaum et al., 2008). Individuals can grow to lengths >150 mm and live for >45 years (Anwar et al., 1990). The mussels attach to the substratum and to each other using tough threads (known as byssus) to create a distinctive biogenic habitat (or reef) that stabilises seabed sediments and can extend over several hectares. Silt, organic waste and shell material accumulate within the structure and further increase the bed height. In this way, horse mussel beds significantly modify sedimentary habitats and provide substrate, refuge and ecological niches for a wide variety of organisms. The beds increase local biodiversity and may provide settling grounds for commercially important bivalves, such as queen scallops. Fish make use of both the higher production of benthic prey and the added structural complexity (OSPAR, 2009). Definition - Beds are formed from clumps of horse mussels and shells covering more than 30% of the seabed over an area of at least 5 m x 5 m. Live adult horse mussels must be present. The horse mussels may be semi-infaunal (partially embedded within the seabed sediments - with densities of greater than 5 live individuals per m2) or form epifaunal mounds (standing clear of the substrate with more than 10 live individuals per clump) (Morris, 2015). -

The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019

SCOTTISH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2019 No. 56 FISHERIES RIVER SEA FISHERIES The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019 Made - - - - 18th February 2019 Laid before the Scottish Parliament 20th February 2019 Coming into force - - 1st April 2019 The Scottish Ministers make the following Regulations in exercise of the powers conferred by section 38(1) and (6)(b) and (c) and paragraphs 7(b) and 14(1) of schedule 1 of the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act 2003( a) and all other powers enabling them to do so. In accordance with paragraphs 10, 11 and 14(1) of schedule 1 of that Act they have consulted such persons as they considered appropriate, directed that notice be given of the general effect of these Regulations and considered representations and objections made. Citation and Commencement 1. These Regulations may be cited as the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019 and come into force on 1 April 2019. Amendment of the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016 2. —(1) The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016( b) are amended in accordance with paragraphs (2) to (4). (2) In regulation 3(2) (prohibition on retaining salmon), for “paragraphs (2A) and (3)” substitute “paragraph (3)”. (3) Omit regulation 3(2A). (a) 2003 asp 15. Section 38 was amended by section 29 of the Aquaculture and Fisheries (Scotland) Act 2013 (asp 7). (b) S.S.I. 2016/115 as amended by S.S.I. 2016/392 and S.S.I. 2018/37. (4) For schedule 2 (inland waters: prohibition on retaining salmon), substitute the schedule set out in the schedule of these Regulations. -

ROYAL NAVY LOSS LIST COMPLETE DATABASE LASTUPDATED - 29OCTOBER 2017 Royal Navy Loss List Complete Database Page 2 of 208

ROYAL NAVY LOSS LIST COMPLETE DATABASE LAST UPDATED - 29 OCTOBER 2017 Photo: Swash Channel wreck courtesy of Bournemouth University MAST is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales, number 07455580 and charity number 1140497 | www.thisismast.org | [email protected] Royal Navy Loss List complete database Page 2 of 208 The Royal Navy (RN) Loss List (LL), from 1512-1947, is compiled from the volumes MAST hopes this will be a powerful research tool, amassing for the first time all RN and websites listed below from the earliest known RN wreck. The accuracy is only as losses in one place. It realises that there will be gaps and would gratefully receive good as these sources which have been thoroughly transcribed and cross-checked. any comments. Equally if researchers have details on any RN ships that are not There will be inevitable transcription errors. The LL includes minimal detail on the listed, or further information to add to the list on any already listed, please contact loss (ie. manner of loss except on the rare occasion that a specific position is known; MAST at [email protected]. MAST also asks that if this resource is used in any also noted is manner of loss, if known ie. if burnt, scuttled, foundered etc.). In most publication and public talk, that it is acknowledged. cases it is unclear from the sources whether the ship was lost in the territorial waters of the country in question, in the EEZ or in international waters. In many cases ships Donations are lost in channels between two countries, eg. -

Hollins 2015

WILDLIFE DIARY AND NEWS FOR DEC 28 - JAN 3 (WEEK 53 OF 2015) Fri 1st January 2016 54 Birds and 45 Flowers to start the year In my garden just before sunrise the moon was close to Jupiter high in the southern sky and Robins and a Song Thrush were serenading it from local gardens as a Carrion Crow flew down to collect the sraps of bread I threw out on the lawn before setting out on my bike in search of birds. Also on my lawn I was surprised to see that a Meadow Waxcap fungus had sprung up a couple of weeks after I thought my garden fungus season was over - later I added another fungus to my day list with a smart fresh Yellow Fieldcap (Bolbitius vitellinus) growing from a cowpat on the South Moors Internet photos of Yellow Fieldcap and Meadow Waxcap My proposed route was along the shore from Langstone to Farlington Marshes lake and as the wind was forecast to become increasingly strong from the south- east, and the tide to be rising from low at 9.0am I thought it best to follow the shore with the wind behind me on the way out and to stick to the cycle track and roads on the way home so I rode down Wade Court Road listening out for garden birds among which I heard bursts of song from more than one Dunnock (not a bird I associate with winter song) and saw two smart cock Pheasants in the horse feeding area immediately south of Wade Court. -

Supplementary Material - Marine Licence Application Lochalsh Algae Farm Sgurr Services Ltd August 2020

Supplementary Material - Marine Licence Application Lochalsh algae farm Sgurr Services Ltd August 2020 This Supplementary Material has been prepared to accompany the Marine Licence Applications (MLA) to Marine Scotland Licensing Operations Team (MS-LOT) by the Applicant (Sgurr Service Ltd Ltd.) for an ‘algal farm’ to trial the natural/wild seeding of kelp on rope in Lochalsh, Highlands. The application is for a full MLA, lasting up to 6 years. The MLA and all supplementary material have been prepared by Kyla Orr Marine Ecological Consulting (the Agent). 1. Site Drawling/Design Figure 1: Site drawing / plans showing surface view of proposed layout at wild seeding trial site, Sgeir ns Caillich, Lochalsh. 2. Site Location: Figure 2: Photograph of proposed site location of wild seeding trials for seaweed (Lochalsh/Sgeir na Caillich) Figure 3: Ordinance survey map showing site boundaries (full extent of the works) for the proposed site/project location. Figure 4: Ordinance survey map showing proposed project location in relation to Marine Protected Areas (MPA). The site falls within the Loch Duich, Long and Alsh MPA. Figure 5: Ordinance survey map showing proposed project location in relation to Special Areas of Conservation (SAC). Figure 7: Marine Conservation Orders and fisheries management measures that restrict fishing activities within and around the proposed site. Figure 8: AIS vessel traffic data over a 1-year period (Jan 2019 - Jan 2020), showing proposed site location is not in a busy vessel traffic area. Obtained from Vessel Finder. 3. Method Statement Sgurr Services Ltd (the Applicant) would like to apply for a marine licence for a small area of the seabed (50m x 20m = 1000m2) to trial wild/natural ‘seeding’ of kelp on rope. -

Engaging the Fishing Industry in Marine Environmental Survey and Monitoring Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 12 No 3

Engaging the Fishing Industry in Marine Environmental Survey and Monitoring Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 12 No 3 G Pasco, B James, L Burke, C Johnston, K Orr, J Clarke, J Thorburn, P Boulcott, F Kent, L Kamphausen and R Sinclair Engaging the Fishing Industry in Marine Environmental Survey and Monitoring European Maritime and Fisheries Fund Project SCO 1500 Final Report Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 12 No 3 G Pasco, B James, L Burke, C Johnston, K Orr, J Clarke, J Thorburn, P Boulcott, F Kent, L Kamphausen and R Sinclair Published by Scottish Government ISSN: 2043-7722 DOI: 10.7489/12365-1 Marine Scotland is the directorate of the Scottish Government responsible for the integrated management of Scotland’s seas. Marine Scotland Science provides expert scientific and technical advice on marine and fisheries issues. Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science is a series of reports that publishes results of research and monitoring carried out by Marine Scotland Science. It also publishes the results of marine and freshwater scientific work carried out for Maine Scotland under external commission. These reports are not subject to formal external peer-review. This report presents the results of marine and freshwater scientific work carried out for Marine Scotland under external commission. © Crown copyright 2021 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-governmentlicence/version/3/ or email: [email protected]. -

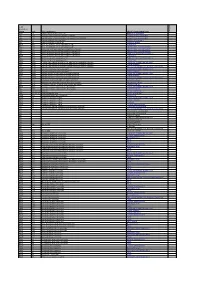

Lead Ecosystem Group Code SBL Habitat Name UKBAP Priority

Lead Ecosystem Group code SBL Habitat name UKBAP Priority habitat name Category M&C H7 Calluna vulgaris-Scilla verna heath Maritime cliff and slopes 3 F&L CG2 Festuca ovina-Helictotrichon pratense grassland Lowland calcareous grassland 1 F&L CG7 Festuca ovina-Hieracium pilosella-Thymus polytrichus grassland Lowland calcareous grassland 1 M&C H7 Calluna vulgaris-Scilla verna heath Maritime cliff and slopes 3 F&L H8 Calluna vulgaris-Ulex gallii heath Lowland heathland 2 F&W M13 Schoenus nigricans-Juncus subnodulosus mire Lowland fens 1 F&L M13 Schoenus nigricans-Juncus subnodulosus mire Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M21 Narthecium ossifragum-Sphagnum papillosum valley mire Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Purple moor grass and rush pastures 2 F&W M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Lowland fens 1 F&L M26 Molinia caerulea-Crepis paludosa fen Purple moor grass and rush pastures 2 F&W M26 Molinia caerulea-Crepis paludosa fen Lowland fens 1 F&W MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh 3 M&C MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Coastal saltmarsh 3 F&L MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Open mosaic habitats on previously developed land 3 F&W MG12 Festuca arundinacea coarse grassland Coastal