Has Collusion Returned to Baseball - Analyzing Whether a Concerted Increase in Free Agent Player Supply Would Violate Baseball's Collusion Clause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Little Moon Lake

Oral history narrative from a joint program with Hillsborough County and the Florida Center for Community Design and Research Little Moon Lake The following narrative is drawn from an interview with Malcolm “Bunny” Mick, a Little Moon Lake resident for over 20 years. An avid fisherman who goes out on the lake three to four times a week, Bunny was able to share his knowledge of the lake’s current condition, as well as its history. Personal History Bunny Mick has lived a fulfilling and interesting life. Being in high school when the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred, Bunny joined the military upon Malcolm "Bunny" Mick (USF) graduation to serve in World War II. While serving, the New York Yankees scouted the young baseball player, who was signed immediately following his release from the military in 1945. Bunny recalled: “I got out December 1st, 1945 and within 30 or 40 days, the Yankees signed me. I played in the Yankee organization for ten years and was kind of back up center fielder behind Joe DiMaggio, the great center fielder. I won three minor league batting titles in three different leagues trying to get his job, but he was the best player I ever saw and I never did really get a good shot at it.” Bunny continued to work in baseball; taking pleasure in the lifestyle and benefits the industry provided him. Despite never beating out Joe DiMaggio, View of lake from the Boy Scout Camp (USF) Bunny enjoyed a secure and happy career, playing and coaching baseball for the majority of his adult life. -

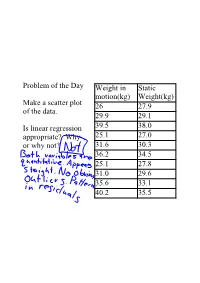

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

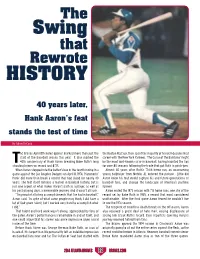

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

Alltime Baseball Champions

ALLTIME BASEBALL CHAMPIONS MAJOR DIVISION Year Champion Head Coach Score Runnerup Site 1914 Orange William Fishback 8 4 Long Beach Poly Occidental College 1915 Hollywood Charles Webster 5 4 Norwalk Harvard Military Academy 1916 Pomona Clint Evans 87 Whittier Pomona HS 1917 San Diego Clarence Price 122 Norwalk Manual Arts HS 1918 San Diego Clarence Price 102 Huntington Park Manual Arts HS 1919 Fullerton L.O. Culp 119 Pasadena Tournament Park, Pasadena 1920 San Diego Ario Schaffer 52 Glendale San Diego HS 1921 San Diego John Perry 145 Los Angeles Lincoln Alhambra HS 1922 Franklin Francis L. Daugherty 10 Pomona Occidental College 1923 San Diego John Perry 121 Covina Fullerton HS 1924 Riverside Ashel Cunningham 63 El Monte Riverside HS 1925 San Bernardino M.P. Renfro 32 Fullerton Fullerton HS 1926 Fullerton 138 Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 1927 Fullerton Stewart Smith 9 0 Alhambra Fullerton HS 1928 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 El Monte El Monte HS 1929 San Diego Mike Morrow 41 Fullerton San Diego HS 1930 San Diego Mike Morrow 80 Cathedral San Diego HS 1931 Colton Norman Frawley 43 Citrus Colton HS 1932 San Diego Mikerow 147 Colton San Diego HS 1933 Santa Maria Kit Carlson 91 San Diego Hoover San Diego HS 1934 Cathedral Myles Regan 63 San Diego Hoover Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1935 San Diego Mike Morrow 82 Santa Maria San Diego HS 1936 Long Beach Poly Lyle Kinnear 144 Escondido Burcham Field, Long Beach 1937 San Diego Mike Morrow 168 Excelsior San Diego HS 1938 Glendale George Sperry 6 0 Compton Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1939 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 Long Beach Wilson San Diego HS 1940 Long Beach Wilson Fred Johnson Default (San Diego withdrew) 1941 Santa Barbara Skip W. -

Major League Baseball

Appendix 1.1 to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 1, Number 2 ( Copyright 2000, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School) MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Note: Information complied from Sports Business Daily, RSV Fax, RSV, Sports Industry Update, Sports Business Journal, and other sources published on or before December12, 2000. Team Principal Owner Most Recent Purchase Price Current Value ($/Mil) ($/Mil) Anaheim Angels Walt Disney Co. $195 Stadium ETA Cost % Facility Financing (millions) Publicly Financed Edison 1966 $24 100% In April 1998, Disney completed a $117 M renovation. International Field Disney contributed $87 M toward the project while the of Anaheim City of Anaheim contributed $30 M through the retention of $10 M in external stadium advertising and $20 M in hotel taxes and reserve funds. Team Principal Owner Most Recent Purchase Price Current Value ($/Mil) ($/Mil) Arizona Jerry Colangelo $130 (1995) $291 Diamondbacks Stadium ETA Cost % Facility Financing (millions) Publicly Financed Bank One Ballpark 1998 $355 76% The Maricopa County Stadium District provided $238 M for the construction through a .25% increase in the county sales tax from April 1995 to November 30, 1997. In addition, the Stadium District issued $15 M in bonds that will be paid off with stadium generated revenue. The remainder was paid through private financing; including a naming rights deal worth $66 M over 30 years. Team Principal Owner Most Recent Purchase Price Current Value ($/Mil) ($/Mil) Atlanta Braves Time Warner $357 Stadium ETA Cost % Facility Financing (millions) Publicly Financed Turner Field 1997 $235 0% The original stadium was built for the 1996 Summer Olympics at a cost of $209 M. -

Columbia Fireflies 2018 Game Notes

COLUMBIA FIREFLIES 2018 GAME NOTES Columbia Fireflies (7-4) @ Greenville Drive (3-8) RHP Marcel Renteria (4/10 v. HAG: 4.1 IP, 4 ER, 6 K) vs. LHP Jhonathan Diaz (1-0, 1.54) Tues., April 17, 2018 — Fluor Field (Greenville, SC) — First Pitch 7:05 p.m. — Game 12 LISTEN: Fox Sports Radio 1400 AM / ColumbiaFireflies.com / iHeartRadio App GLOW POINTS NEWS & NOTES CONTENTS ABOUT LAST GAME: Columbia’s pitchers overpowered Greenville on Pages 2: Today’s Starting Pitcher SAL South 1H Standing: T-2nd (-1.0) Page 3: Manager & Coaching Staff Home Record: 4-3 Monday. The staff struck out a franchise-record tying 17 hitters and Pages 4-6: Individual Hitting Notes Road Record: 3-1 won the series opener, 7-1. Day Record: 0-1 Page 7: Extra Hitting Notes Night Record: 7-3 Pages 8-9: Bullpen Notes 17 AGAIN: The 17 strikeouts tied the franchise mark for a single game Page 10: Miscellaneous Pitching Notes Road Trip: 3-1 set on June 22, 2017 vs. the Kannapolis Intimidators. Every Drive Page 11: Season Highs and Lows Streak: W2 Page 12: Transactions hitter on Monday struck out at least once. You can thank these arms: Sunday: 0-1 Page 13: Day-by-Day Results Monday: 2-0 • Chris Viall: 11 K (a career-high), 5 IP Tuesday: 0-1 Wednesday:1-0 • Darwin Ramos: 3 K, 2 IP vs. Greenville (1-0, 1-0 Away) Thursday: 2-0 Friday: 1-1 • Carlos Hernandez: 3 K, 2 IP Saturday: 1-1 April 16 Away W, 7-1 April: 7-4 CAN’T HANDLE THE HEAT: Columbia’s pitching staff has fanned 117 April 17 Away 7:05 p.m. -

Kash Beauchamp Was Born Into Baseball. His Father Jim

Kash Beauchamp was born into baseball. His father Jim Beauchamp spent 50 years in professional baseball, playing 10 in the Major Leagues for five different teams, was Bobby Cox's bench coach for 9 years where the Atlanta Braves won 9 division titles, a world championship, and three pennants. Jim spent the remainder of his career with the Braves as the supervisor for minor league field operations until his passing on Christmas day in 2008. The experience of growing up in the game obviously impacted Kash Beauchamp's career. After a stellar high school career as a three sport athlete, Kash accepted a scholarship to Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma where he was immediately drafted as the first overall pick in the January, 1982 Major League Baseball Draft ahead of such future stars as Kirby Puckett and Randy Meyers. Beauchamp began his pro career in Medicine Hat where he was a member of the 1982 Pioneer League Champion Medicine Hat Blue Jays. Kash garnered all-star honors after hitting .320 and playing terrific defense in center field. Beauchamp was promoted to the South Atlantic League in 1983 where he played on a star studded team that included, Cecil Fielder, Jose Mesa, Pat Borders, Fred McGriff and David Wells. In 1984 Beauchamp was again promoted to the Carolina League where while playing for the Kinston Blue Jays, he was the MVP of the Carolina League All-Star game by going 5-6 with two triples and a HR with 5 RBI. The same year Beauchamp was voted by Baseball America as the Best Defensive Outfielder and Outfielder with the Best Arm. -

NABF Tournament News 09.Indd

November 1, 2009 • Bowie, Maryland • Price $1.00 95th Year Graduate of the Year NABF Graduates of the Year NABF Honors 1968 Bill Freehan (Detroit Tigers) 1969 Pete Rose (Cincinnati Reds) 1970 Bernie Carbo (Cincinnati Reds) 1971 Ted Simmons (St. Louis Cardinals) Zack Greinke 1972 John Mayberry (Kansas City The National Amateur Base- Royals) 1973 Sal Bando (Oakland Athletics) ball Federation is honoring Kan- 1974 Jim Wynn (Los Angeles Dodgers) sas City Royals pitcher Zack 1975 Frank Tanana (California Angels) Greinke is its 2009 Graduate of 1976 Rick Manning (Cleveland Indians) 1977 Kenton Tekulve (Pittsburgh the Year. Pirates) Greinke played on the NABF 1978 Lary Sorenson (Milwaukee 18 and under National Team in Brewers) 1979 Willie Horton (Seattle Mariners) 2001 in Joplin, Missouri — the 1980 Britt Burns (Chicago White Sox) fi rst year USA Baseball was in- 1981 Tom Paciorek (Seattle Mariners) 14 and under NABF Regional Classic Tournament action at Detwiler Park in Toledo, volved in the Tournament of 1982 Leon Durham (Chicago Cubs) Ohio (NABF photo by Harold Hamilton/www.hehphotos.lifepics.com). 1983 Robert Bonnell (Toronto Blue Stars. Jays) "He came to us 1984 Jack Perconte (Seattle Mariners) as a shortstop and 1985 John Franco (Cincinnati Reds) 2009 NABF Annual Meeting 1986 Jesse Barfi eld (Toronto Blue a possible pitcher," Jays) says NABF board 1987 Brian Fletcher (Texas Rangers) to be in Annapolis, Maryland member and na- 1988 Allen L. Anderson (Minnesota Twins) tional team busi- The 95th Annual Meeting of 1989 Dave Dravecky (San Fransisco ness manager Lou Tiberi. Giants) the National Amateur Baseball Greinke played shortstop and 1990 Barry Larkin (Cincinnati Reds) Federation will be Thursday, 1991 Steve Farr (New York Yankees) hit fourth during the fi rst four November 5 to Sunday, Novem- 1992 Marquies Grissom (Montreal games of the TOS. -

Lake Padre Padre Project Moving Slowly

Inside the Moon Art Walk A2 Seashore A2 Cotillion A4 Fishing A11 Live Music A18 Issue 709 The Photo by Miles Merwin Island Free The voiceMoon of The Island since 1996 November 16, 2017 Weekly www.islandmoon.com FREE Kickoff party Tuesday, Around Lake Padre Padre Project December 5 The Island La Posada By Dale Rankin Moving Slowly In Matador, about 80 miles northeast of Lubbock deer season took a Pending settlement may allow work to continue is Largest slithery turn when hunters lifted a blind to find twenty-six rattlesnakes living underneath. Single Toys for Tots Event in Texas Off the coast of Portugal a Prehistoric, Dinosaur-Era Shark with scary teeth was sighted Work has stopped in the area around Lake Padre and on land adjacent to the Schlitterbahn waterpark pending a hearing in a bankruptcy court in San Antonio on December 4. The canals leading to the site of the proposed SPID/Park Road 22 Water Exchange Bridge are in place and the recently dug canal at the south end of the park site, see photo, stops just short of connecting to the current Island canal system north The La Posada Lighted Boat Parade Things haven’t been that exciting of Whitecap. and the surrounding events began here on our little sandbar but we more than thirty years ago when the have been dealing with own set of The City of Corpus Christi has earmarked a total of $11.5 million to building the Water Exchange Bridge and has a bid in place for construction, but has not population of The Island was less predators and like OTB type one than 5000 souls. -

2017 Game Notes

2017 GAME NOTES American League East Champions 1985, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993, 2015 American League Champions 1992, 1993 World Series Champions 1992, 1993 Toronto Blue Jays Baseball Media Department Follow us on Twitter @BlueJaysPR Game #93, Road #47 (21-25), TORONTO BLUE JAYS (43-49) at BOSTON RED SOX (52-42), Tuesday, July 18, 2017 PROBABLE PITCHING MATCHUPS: (All Times Eastern) Tuesday, July 18 at Boston Red Sox, 7:10 pm…LHP J.A. Happ (3-6, 3.54) vs. LHP Brian Johnson (2-0, 4.29) Wednesday, July 19 at Boston Red Sox, 7:10 pm…RHP Aaron Sanchez (1-2, 3.94) vs. LHP Drew Pomeranz (9-4, 3.75) Thursday, July 20 at Boston Red Sox, 1:35 pm…TBA vs. RHP Doug Fister (0-3, 6.75) 2017 AT A GLANCE ON THE ROAD AGAIN: Record ................................................................. 43-49, T-4th, 8.0 GB Tonight, Toronto continues its 10-day, 10-game road trip (2-2) with Home Attendance (Total & Average) ...................... 1,823,669/39,645 the second scrimmage of a four-game set in Boston…Will finish the Sellouts (2017) ................................................................................ 11 trip with a three-game series in Cleveland (48-43) starting on Friday. 2016 Season Record after 92 Games ........................................ 51-41 The Jays are 21-25 on the road this season but have gone 13-10 in 2016 Season Record after 93 Games ........................................ 51-42 their last 23 contests, including wins in 5 of the last 8 games…Have hit 10 homers in the last 5 road contests and rank 5th in the AL with Come From Behind Wins ............................................................... -

Front Page 9-10-16.Indd

DETROIT TIGERS GAME NOTES WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS: 1935, 1945, 1968, 1984 Detroit Tigers Media Rela ons Department • Comerica Park • Phone (313) 471-2000 • Fax (313) 471-2138 • Detroit, MI 48201 www. gers.com • @ gers, @TigresdeDetroit, @DetroitTigersPR Detroit Tigers (76-64) vs. BalƟ more Orioles (76-64) Saturday, September 10, 2016 • Comerica Park, Detroit, MI • 7:10 p.m. ET RHP Jordan Zimmermann (9-5, 4.44) vs. RHP Ubaldo Jimenez (6-11, 6.19) Game #141 • Home Game #69 • TV: FOX Sports Detroit/MLB Network • Radio: 97.1 FM RECENT RESULTS: The Tigers opened their series numbers against the Orioles. Cabrera is ba ng .377 TIGERS AT A GLANCE against the Orioles with a 4-3 win on Friday night at (81x215) with 41 runs scored, 10 doubles, one triple, Overall ............................................................. 76-64 Comerica Park. With the game ed 3-3, Victor Mar nez 20 home runs and 59 RBI in 56 games vs. Bal more. He Current Streak ...................................................W1 hit a solo home run, his 24th of the season, to put the leads all ac ve players with a .458 on-base percentage At Comerica Park ...........................................40-28 Tigers in front. J.D. Mar nez drove in two runs and was and a .712 slugging percentage vs. the Orioles, while he On the Road...................................................36-36 3x3 with a walk, while Ian Kinsler and Cameron Maybin is second with a .377 ba ng average. Cabrera has hit Day games .....................................................31-21 each had two hits. Alex Wilson picked up his third win safely in 23 of his last 26 games vs.