Mood Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clinical Picture of Depression in Preschool Children

The Clinical Picture of Depression in Preschool Children JOAN L. LUBY, M.D., AMY K. HEFFELFINGER, PH.D., CHRISTINE MRAKOTSKY, PH.D., KATHY M. BROWN, B.A., MARTHA J. HESSLER, B.S., JEFFREY M. WALLIS, M.A., AND EDWARD L. SPITZNAGEL, PH.D. ABSTRACT Objective: To investigate the clinical characteristics of depression in preschool children. Method: One hundred seventy- four subjects between the ages of 3.0 and 5.6 years were ascertained from community and clinical sites for a compre- hensive assessment that included an age-appropriate psychiatric interview for parents. Modifications were made to the assessment of DSM-IV major depressive disorder (MDD) criteria so that age-appropriate manifestations of symptom states could be captured. Typical and “masked” symptoms of depression were investigated in three groups: depressed (who met all DSM-IV MDD criteria except duration criterion), those with nonaffective psychiatric disorders (who met cri- teria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and/or oppositional defiant disorder), and those who did not meet criteria for any psychiatric disorder. Results: Depressed preschool children displayed “typical” symptoms and vegetative signs of depression more frequently than other nonaffective or “masked” symptoms. Anhedonia appeared to be a specific symptom and sadness/irritability appeared to be a sensitive symptom of preschool MDD. Conclusions: Clinicians should be alert to age-appropriate manifestations of typical DSM-IV MDD symptoms and vegetative signs when assessing preschool children for depression. “Masked” symptoms of depression occur in preschool children but do not predomi- nate the clinical picture. Future studies specifically designed to investigate the specificity and sensitivity of the symp- toms of preschool depression are now warranted. -

Week 3 Emotional Regulation

WEEK 3 EMOTIONAL REGULATION GOALS/OBJECTIVES: This optional treatment module contains information to allow the participants to better understand how their TBI is related to their emotional dysregulation. This module should be utilized if several participants have expressed issues with mood swings, or if collateral information suggests client issues with emotional dysregulation. Emotional dysregulation refers to the inability of a person to control or regulate their emotional responses to provocative stimuli. The primary goals of this week will be for participants to: ❑ Identify what occurs during their mood swings ❑ Better understand their emotional responses to various situations ❑ Allow participants to practice coping skills to reduce or navigate emotional outbursts ❑ Provide psycho-education on how emotional dysregulation is related to TBI, and facilitate discussion during group about coping with emotional dysregulation. T I M E : Allow 1.5 hours for the session. NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS: A minimum of four participants is recommended. © MINDSOURCE – Brain Injury Network 2018 WEEK 3 44 WEEK 3 PREPARATION VIDEO Watch the following video: https://youtu.be/Y02clqBzrbs For trainer info on emotional dysregulation and TBI, see: https://tinyurl.com/ahead-trainerinfo PRINT HANDOUTS ❑ Brain Injury and Emotion Regulation ❑ Mood Log ❑ Take Home Impressions These handouts can be found in the handout section for this week, the facilitator’s guide will indicate when these should be referenced. WRITE Write the following group rules on the white board for reference for participants throughout the treatment group: • Confidentiality: The information we discuss in this group is private, and members are expected to keep it that way. • Respect: Give your attention and consideration to participants, and they will do the same for you. -

Anxiety and Depression in Older Adults

RESEARCH BRIEF #8 ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION IN OLDER ADULTS 150 000 elderly people suffer from depression in Swedenà Approximately half of older adults with depression in population surveys have residual problems several years later à Knowledge about de- pression and anxiety in older adults is limited, even though these conditions can lead to serious nega- tive consequences à More research is needed on prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is associated with 1. Introduction a constant anxiety and excessive fear and anxiety about various everyday activities (anticipatory anxiety). Sweden has an ageing population. Soon every fourth Panic disorder is associated with panic attacks (distinct person in Sweden will be over 65. Depression and anxiety periods of intense fear, terror or significant discomfort). disorders are common in all age groups. However, these Specific phobia is a distinct fear of certain things or conditions have received significantly less attention than situations (such as spiders, snakes, thunderstorms, high SUMMARY dementia within research in the older population (1, 2). altitudes, riding the elevator or flying). The number of older people is increasing Psychiatry research has also neglected the older popu- Social phobia is characterised by strong fear of social situ- across the world. Depression and anxiety lation. Older people with mental health problems are ations involving exposure to unfamiliar people or to being is common in this age group, as among also a neglected group in the care system, and care varies critically reviewed by others. Forte is a research council that funds and initiates considerably between different parts of the country. -

Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Mild Depression

Research and Reviews Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Mild Depression JMAJ 54(2): 76–80, 2011 Tomifusa KUBOKI,*1 Masahiro HASHIZUME*2 Abstract The chief complaint of those suffering from mild depression is insomnia, followed by physical symptoms such as fatigability, heaviness of the head, headache, abdominal pain, stiffness in the shoulder, lower back pain, and loss of appetite, rather than depressive symptoms. Since physical symptoms are the chief complaint of mild depres- sion, there is a global tendency for the patients to visit a clinical department rather than a clinical psychiatric department. In Mild Depression (1996), the author Yomishi Kasahara uses the term “outpatient depression” for this mild depression and described it as an endogenous non-psychotic depression. The essential points in diagnosis are the presentation of sleep disorders, loss of appetite or weight loss, headache, diminished libido, fatigability, and autonomic symptoms such as constipation, palpitation, stiffness in the shoulder, and dizziness. In these cases, a physical examination and tests will not confirm any organic disease comparable to the symptoms, but will confirm daily mood fluctuations, mildly depressed state, and a loss of interest and pleasure. Mental rest, drug therapy, and support from family and specialists are important in treatment. Also, a physician should bear in mind that his/her role in the treatment differs somewhat between the early stage and chronic stage (i.e., reinstatement period). Key words Mild depression, Outpatient depression, -

Intervention a Process – Not an Event

Intervention A Process – Not an Event ® La Hacienda PO Box 1, 145 La Hacienda Way Hunt, Texas 78024 (800) 749-6160 www.lahacienda.com Table of Contents (Please Note: Throughout this guide, items in bold italics are not printed in the Participant’s Guide.) What, Why and How of Intervention 1 Intervention Program Description 2 Rights of Intervention Program Participants 3 Responsibilities of Intervention Program Participants 3 Outline of the Intervention Process 4 The Disease 5 Nature of the Disease 6 Progression of the Disease 7 Delusional Memory 8 The Intervention Concept and Goal 9 Intervention Presentation Guidelines 10 Documentation Preparation 12 Suggested Feelings Words 13 Documentation Sheet Example 14 Documentation Sheet 15 Substance Abuse: A Family Problem 16 Symptoms of Co-Dependency 17 Enabling 18 Enabling Worksheet 19 What Goes on in a Family? 20 Intervention Planning Worksheet 21 Practice of Presentations 22 Your Intervention Rules 23 Intervention Checklist and Last Minute Reminders 24 This page intentionally left blank. What, Why and How of Intervention What is Intervention? Why Intervene? In its simplest form, intervention on Alcoholism is a progressive, alcoholism or drug addiction happens each terminal disease characterized by time the dependent person is confronted delusion and denial. Left to his/her own with his/her use or related behavior. This devices, the addicted individual is doomed form of intervention is inadequate and to continue their downward spiral. They counterproductive. Following such an have a disease that makes them think they encounter the addiction worsens and the do not have a disease! We believe that the family and friends of the dependent become belief that an alcoholic/addict must “hit angry and frustrated and may avoid further bottom” and ask for help is a deadly myth. -

Life Mental Health

LIFE MENTAL HEALTH BIPOLAR MOOD DISORDERS TREATMENT & REFERRAL GUIDE MHealth–BR–005 Rev 2 January 2019 LIFE MENTAL HEALTH Bipolar Mood Disorders – Treatment Guide ■ How to recognise Bipolar Mood Disorder ■ Who to approach for treatment ■ Treatment options ■ Self help BIPOLAR MOOD DISORDER Bipolar mood disorder is more than just a simple mood swing. You may experience a sudden dramatic shift in the extremes of emotions. These shifts seem to have little to do with external situations. In the manic or high phase of the illness you are not just happy, but rather, ecstatic. A great burst of energy can be followed by severe depression, which is the low phase of the disease. Periods of fairly normal moods can be experienced between cycles. These cycles are different for different people. They can last for days, weeks, or even months. Although bipolar mood disorder can be disabling, it also responds well to treatment. Since many other diseases can masquerade as bipolar mood disorder, it is important that the person undergoes a complete medical evaluation as soon as possible after the first symptoms occur. What is bipolar mood disorder? Bipolar mood disorder is a physical illness marked by extreme changes in mood, energy and behaviour. That is why doctors classify it as a mood disorder. Bipolar mood disorder – which used to be known as manic depressive illness – is a mental illness involving episodes of serious mania and depression. The person’s mood usually swings from overly high and irritable to sad and hopeless, and then back again, with periods of normal mood in between. -

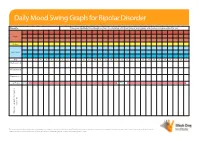

Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder

Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder Month: Please use this Daily Mood Graph to chart mood swings and the effects of any triggers and medications prescribed for you. Highs Normal Depressed Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Medication A Medication B Medication C e.g. Prozac 20mg 40mg events, etc. events, Notes on sleep patterns, triggers, triggers, on sleep patterns, Notes This document may be freely downloaded and distributed on condition no change is made to the content. The information in this document is not intended as asubstitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Not to be used for commercial purposes and not to be hosted electronically outside of the Black Dog Institute website. www.blackdoginstitute.org.au Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder Instructions 1. Rate your mood at the end of each day by placing an ‘X’ in the appropriate box. If you have experienced both a ‘high’ and a ‘low’ mood on any given day, please rate both by putting an ‘X’ at each level 2. Write the name of the medications and doses you are taking 3. Next to each medication, please indicate the period of time you took the medication at the same dose by drawing an arrow through the relevant dates. If your dose changes during the course of the charting period, please write the new dose in the relevant box and continue the line. -

The Problem of Comorbidity

Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 14. No. 6, pp. 585-603, 1994 Pergamon Copyright 0 1994 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0272-7358/94 $6.00 + .OO 0272-7358(94)E0017-5 UNMASKING UNMASKED DEPRESSION IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: THE PROBLEM OF COMORBIDITY Constance Han-men University of California, Los Angeles Bruce E. Compas University of Vermont ABSTRACT. The unmasking of childhood depression has stimulated considerable research, but the field has drifted unintentionally toward the rezfication of childhood depression as an entity. In turn, the reification, often embodied in theform of diagnostic categorization, may contribute to premature closure on our understanding of childhood and adolescent depression. One of the major una%rem+sized characteristics of depression is that it rarely occurs by itself in children. Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception, and thus, much of what we think we know about the disorder may be shaped by its co-occurrence with other disorders and symptoms. Accordingly, we discuss the conceptual and measure- ment issues in depression in youngsters, identify the extent of comorbidity, and then discuss some of the implications of comorbidity. Several research issues are raised concerning exploration of the meaning of comorbidity and its possible origins. PREVAILING beliefs about childhood depression that were common until fairly recently have generally been dispelled: “if it exists at all it is rare”; “if it exists it is masked as a depression equivalent such as behavior and conduct problems, school difficulties, somatic complaints, or adolescent turmoil”; “it is transitory”; “it is a developmentally normal stage.” Dispelling the first two myths, Carlson and Cantwell (1980) demonstrated that many children referred for treatment for other problems actually met adult diagnostic criteria for depression if only the clinician looked beyond the “masking” symptoms. -

Depression in Early Childhood

CHAPTER 25 Depression in Early Childhood Joan L. Luby Diana Whalen Only in the last 10 years have the mental health rized that several core emotions are present at and developmental communities generally ac- birth in the human infant. Subsequently, em- cepted that depression may arise in very early pirical studies provided support for this hypoth- childhood. As early as the 1940s, clinical de- esis (e.g., Izard, Huebner, Risser, & Dougherty, pression was observed and described in infants 1980). Despite these early insights, a significant deprived of primary caregiving relationships body of empirical data that began to outline the (Spitz, 1946). However, in subsequent years, trajectory of early emotion development did not prevailing developmental theory suggested that become available until the late 1980s. Over the young children are too immature to experience last two decades, data informing how children the core emotions of depression, thereby ruling recognize and express discrete emotions, devel- out the possibility of clinical depression before op the ability to regulate emotional responses, school age (Rie, 1966). Subsequent advances in understand the causes and consequences of studies of early childhood emotion development emotions, as well as experience more complex provided data refuting this claim, demonstrat- emotions, have become available (for review, ing the previously unrecognized emotional so- see Denham, 1998; Saarni, 1999). While these phistication of infants and toddlers (Denham, data have provided a broad framework illustrat- 1998; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). Despite this, ing that emotional competence develops earlier empirical data to validate and describe a clini- in life than previously recognized, many details cal depressive syndrome in infants and toddlers about when and how emotional development under the age of 3 years remains scarce, with unfolds in the infancy and preschool period re- some retrospective data suggesting it may arise main understudied. -

Assessment of Childhood Depression

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Volume 11, No. 2, 2006, pp. 111–116 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00395.x Assessment of Childhood Depression Allan Chrisman, Helen Egger, Scott N. Compton, John Curry & David B. Goldston Box 3492, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Background: Depression as a disorder in childhood began to be increasingly recognised in the 1970s. Epi- demiologic community and clinic-based studies have characterised the prevalence, clinical course, and complications of this illness throughout childhood and adolescence into adulthood. This paper reviews two instruments for assessing depression in prepubertal children – the Dominic Interactive and The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment. Both instruments are useful in screening for psychiatric disorders and reliably identifying the presence of depressive symptoms in young children. Keywords: Depression; assessment; childhood; PAPA; Dominic Interactive Introduction depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder and depressive disorder not otherwise specified. The recognition that depressive syndromes and dis- In depression, children may report feeling sad, un- orders exist in young people is a relatively recent happy, bored or disinterested in usual activities, angry or development. In the mid-twentieth century, when psy- irritable, or may appear sad or tearful (APA, 1994). The choanalytic theory provided the primary conceptual diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) requires at model for psychiatric disorders, clinicians rarely -

Bipolar Disorder Symptoms

Bipolar disorder symptoms What this fact sheet covers: • What is bipolar disorder • Sub-types of bipolar disorder • Symptoms of bipolar disorder • When to seek help for bipolar disorder • Key points to remember • Where to get more information What is bipolar disorder? Distinguishing between bipolar I Bipolar disorder is the name used to describe a and bipolar II set of ‘mood swing’ conditions, the most severe Bipolar I disorder is the more severe disorder, form of which used to be called ‘manic depression’. in the sense that individuals are more likely to The term describes the exaggerated swings of experience ‘mania’, have longer ‘highs’ and to mood, cognition and energy from one extreme to have psychotic episodes and be more likely to be the other that are characteristic of the illness. hospitalised. People with this illness suffer recurrent episodes Mania refers to a severely high mood where of high, or elevated moods (mania or hypomania) the individual often experiences delusions and/ and depression. Most experience both the highs or hallucinations. The severe highs which are and the lows. Occasionally people can experience referred to as ‘mania’ tend to last days or weeks. a mixture of both highs and lows at the same time, or switch during the day, giving a ‘mixed’ picture of symptoms. A very small percentage of sufferers Bipolar II disorder is defined as being less severe, of bipolar disorder only experience the ‘highs’. in that there are no psychotic features and People with bipolar disorder experience normal episodes tend to last only hours to a few days; a moods in between their mood swings. -

Hypochondriasis and Disease-Claiming Behaviour in Generalpractice A

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE Hypochondriasis and disease-claiming behaviour in generalpractice A. R. DEWSBURY, M.R.C.G.P., D.P.M. Birmingham Problems of definition Hypochondriasis presents as a frequent problem in general practice. There is a need both to exclude physical illness and to protect the patient from unnecessary and expensive referrals and investigations. The hypochondriac is also prone to invoke anger in the physician as the patient continues to complain, refuses to accept reassurance or acts aggressively. Both anger and undue sympathy interfere with objective treatment. The hypochondriac is a problem for the taxonomist. The term was coined to describe patients with abdominal symptoms accompanied by mood disturbance (Gillespie, 1929). However the term is now more commonly used to describe patients presenting a bodily complaint for which no adequate physical cause can be found (Brown, 1936). For some authors hypo¬ chondriasis can be equated with depression (Kenyon, 1964). Others stress a multiplicity of complaints (Ray and Advanti, 1962), so that their patients resemble hysteria (in the sense defined by Guze and Perley in 1963). Thus Richards (1940) talks of hypochondriasis as a simple or diffuse eruption of somatic complaints. In order to study hypochondriasis appearing in general practice, attention was paid to what Pilowsky (1969) called "abnormal illness behaviour". In this category it was possible to include simultaneously: (1) those with sensations mimicking physical disease (sensohypochondriacs of Leonhard, 1961), (2) those convinced, without foundation, of specific physical illness (ideohypochondriacs), (3) those claiming illness, without the physician being sure that the patient had either of the above experiences (malingering). This avoids the need to conjecture as to the contents of the patient's consciousness as well as certain semantic difficulties.