Three Flute Chamber Works by Alberto Ginastera: Intertwining Elements of Art and Folk Music Breta L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

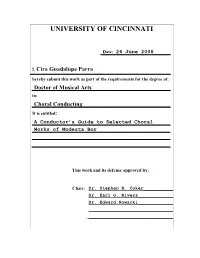

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, Y Las Dos Orillas Del Río De La Plata

Aharonián, Coriún Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, y las dos orillas del Río de la Plata Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Aharonián, Coriún. “Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, y las dos orillas del Río de la Plata” [en línea]. Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” 26,26 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/ayestaran-vega-dos-orillas-rio.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, Buenos Aires, 2012, pág. 203 LAURO AYESTARÁN, CARLOS VEGA, Y LAS DOS ORILLAS DEL RÍO DE LA PLATA CORIÚN AHARONIÁN Resumen El texto explora el diálogo de las dos figuras fundacionales de la musicología de Argentina y Uruguay: de Vega como maestro y Ayestarán como discípulo, y de ambos como amigos. La rica correspondencia que mantuvieran durante casi tres décadas permite recorrer diversas características de sus personalidades, que se centran obsesivamente en el rigor y en la entrega pero que no excluyen el humor y la ternura. Se aportan observaciones acerca de la compleja relación de ambos con otras personalidades del medio musical argentino. -

Music and Spiritual Feminism: Religious Concepts and Aesthetics

Music and spiritual feminism: Religious concepts and aesthe� cs in recent musical proposals by women ar� sts. MERCEDES LISKA PhD in Social Sciences at University of Buenos Aires. Researcher at CONICET (National Council of Scientifi c and Technical Research). Also works at Gino Germani´s Institute (UBA) and teaches at the Communication Sciences Volume 38 Graduation Program at UBA, and at the Manuel de Falla Conservatory as well. issue 1 / 2019 Email: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9692-6446 Contracampo e-ISSN 2238-2577 Niterói (RJ), 38 (1) abr/2019-jul/2019 Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication is a quarterly publication of the Graduate Programme in Communication Studies (PPGCOM) at Fluminense Federal University (UFF). It aims to contribute to critical refl ection within the fi eld of Media Studies, being a space for dissemination of research and scientifi c thought. TO REFERENCE THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE USE THE FOLLOWING CITATION: Liska, M. (2019). Music and spiritual feminism. Religious concepts and aesthetics in recent musical proposals by women artists. Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication, 38 (1). Submitted on: 03/11/2019 / Accepted on: 04/23/2019 DOI – http://dx.doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v38i1.28214 Abstract The spiritual feminism appears in the proposal of diverse women artists of Latin American popular music created recently. References linked to personal and social growth and well-being, to energy balance and the ancestral feminine powers, that are manifested in the poetic and thematic language of songs, in the visual, audiovisual and performative composition of the recitals. A set of multi religious representations present in diff erent musical aesthetics contribute to visualize female powers silenced by the patriarchal system. -

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003 The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire by Bonny Kathleen Winston, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2003 Dedication This dissertation would not have been completed without all of the love and support from professors, family, and friends. To all of my dissertation committee for their support and help, especially John Geringer for his endless patience, Betty Mallard for her constant inspiration, and Martha Hilley for her underlying encouragement in all that I have done. A special thanks to my family, who have been the backbone of my music growth from childhood. To my parents, who have provided unwavering support, and to my five brothers, who endured countless hours of before-school practice time when the piano was still in the living room. Finally, a special thanks to my hall-mate friends in the school of music for helping me celebrate each milestone of this research project with laughter and encouragement and for showing me that graduate school really can make one climb the walls in MBE. The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire Publication No. ________________ Bonny Kathleen Winston, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisor: John M. Geringer The purpose of this dissertation was to create an on-line database for intermediate piano repertoire selection. -

Toward a Redefinition of Musical Learning in the Saxophone Studios of Argentina

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Toward a redefinition of musical learning in the saxophone studios of Argentina Mauricio Gabriel Aguero Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Aguero, Mauricio Gabriel, "Toward a redefinition of musical learning in the saxophone studios of Argentina" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2221. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2221 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. TOWARD A REDEFINITION OF MUSICAL LEARNING IN THE SAXOPHONE STUDIOS OF ARGENTINA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Mauricio Gabriel Agüero B.M., Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, 2005 M.M., University of Florida, 2010 December 2013 Acknowledgments This monograph would not have been possible without the help of many people. Most important, I want to thank to my Professor and advisor Griffin Campbell, who guided my studies at LSU for the last three years with his musical passion, artistry and great teaching ability. As a brilliant saxophonist and thoughtful educator, Professor Campbell has been an important mentor and role model for me. -

ISU Symphony Orchestra

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music Spring 3-25-2018 ISU Symphony Orchestra Glenn Block, Director Illinois State University Jorge Lhez, Conductor Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Block,, Glenn Director and Lhez,, Jorge Conductor, "ISU Symphony Orchestra" (2018). School of Music Programs. 3657. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/3657 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THANKYOU Illinois State University College of Fine Arts Illinois State University College ofFine Arts School of Music Jean M. Miller, Dean, College of Fine Arts Laurie Thompson-Merriman, Associate Dean of Creative Scholarship and Planning Janet Tulley, Assistant Denn of Acndemic Programs and Student Affairs Steve Parsons, Director, School of Music Janet Wilson, Director, School of Theatre and Dance l'.lichael \Ville, Director, School of Art Aaron Paolucci, Pro~m Director, Arts Technology • • Nick Benson, Center for Performing Arts l\fanager Barry Blinderm:m, Director, University Galleries Illinois State University School ofMusic Illinois State University Symphony Orchestra A. Oforiwaa Aduonurn, E1bnon111Iimlog Marie I-~bonville, MJ1sitology Allison Alcorn, M11si,vlog Katherine J. Lewis, Viola Debra Austin, Voia Roy D. l\Iagnuson, Theory a11d Con,po.ritio11 Glenn Block, M11sic Director Mark Babbitt, Trombon, Anthony Marinello III, Diru/orofBa11ds Jorge Lhez (Argentina), Guest Conductor Emily Beinbom, Murie Th,rapy Thomas Marko, Dirrclor of]a:::.:;_ Studi,s Glenn Block, Orrhu/T/1 and Conduclin.!, Rose Marshack, A-fmi,· Bmin,ss a11d Arts T,dmolog Shela Bondurant Koehler, Mmk Edrm,tion Joseph Matson, Musimlog Karyl K. -

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-Year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina Hello everyone, my name is Qiwen Wan. I am a first-year doctoral student in piano pedagogy major at the University of South Carolina. I am really glad to be here and thanks to SCMTA to allow me to present online under this circumstance. The topiC of my lightning talk is 5 stages for teaChing Alberto Ginastera's Twelve AmeriCan Preludes. First, please let me introduce this colleCtion. Twelve AmeriCan Preludes is composed by Alberto Ginastera, who is known as one of the most important South AmeriCan composers of the 20th century. It was published in two volumes in 1944. In this colleCtion, there are 12 short piano pieCes eaCh about one minute in length. Every prelude has a title, tempo and metronome marking, and eaCh presents a different charaCter or purpose for study. There are two pieCes that focus on a speCifiC teChnique, titled Accents, and Octaves. No. 5 and 12 are titled with PentatoniC Minor and Major Modes. Triste, Creole Dance, Vidala, and Pastorale display folk influences. The remaining four pieCes pay tribute to other 20th-Century AmeriCan composers. This set of preludes is an attraCtive output for piano that skillfully combines folk Argentine rhythms and Colors with modern composing teChniques. Twelve American Preludes is a great contemporary composition for late-intermediate to early-advanced students. In The Pianist’s Guide to Standard Teaching and Performing Literature, Dr. Jane Magrath uses a 10-level system to list the pieCes from this colleCtion in different levels. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

Música Infancias Visuales Artes Performáticas Talleres Literatura Podcasts Ferias Cine Audiovisual Transmisiones En Vivo Contenidos

Semana del 4 al 7 de marzo de 2021 música infancias visuales artes performáticas talleres literatura podcasts ferias cine audiovisual transmisiones en vivo Contenidos página 04 / Música Autoras Argentinas Porque sí Homenaje a Claudia Montero Música académica en el Salón de Honor Himno Nacional Argentino Nuestrans Canciones: Brotecitos Mujer contra mujer. 30 años después Un mapa 5 Agite musical Infancias 30/ Mujeres y niñas mueven e inventan el mundo Un mapita 35/ Visuales Cuando cambia el mundo. Preguntas sobre arte y feminismos Premio Adquisición Artes Visuales 8M Performáticas 39/ Agite: Performance literaria Presentaciones de libros Archivo vivo: mujeres x mujeres Malambo Bloque Las Ñustas Vengan de a unx Talleres 50/ Nosotres nos movemos bajo la Cruz del Sur Aproximación a la obra de Juana Bignozzi Poesía cuir en tembladeral 54/ Ferias Feria del Libro Feminista Nosotras, artesanas Audiovisual 59/ Cine / Contar Bitácoras Preestrenos Conversatorios Transmisiones en vivo Pensamiento 66/ Conversatorios Podcasts: Alerta que camina Podcasts: Copla Viva 71/ Biografías nosotras movemos el mundo Segunda edición 8M 2021 Mover el mundo, hacerlo andar, detenerlo y darlo vuelta para modifcar el rumbo. Mover el mundo para que se despierte de esta larga pesadilla en la que algunos cuerpos son posesión de otros, algunas vidas valen menos, algunas vidas cuestan más. Hoy, mujeres y diversidades se encuentran en el centro de las luchas sociales, son las más activas, las más fuertes y también las más afectadas por la desposesión, por el maltrato al medioambiente, por la inercia de una sociedad construida a sus espaldas pero también sobre sus hombros. Nosotras movemos al mundo con trabajos no reconocidos, con nuestro tiempo, con el legado invisible de las tareas de cuidado. -

Alberto Ginastera

FUNDACION JUAN MARCH HOMENAJE A Alberto Ginastera Miércoles, 20 de abril de 1977, 20 horas. PROGRAMA ALBERTO GINASTERA. Quihteto para piano y cuarteto de cuerdas, Op. 29 (1963). I. Introduzione. II. Cadenza I per viola e violoncello. III. Scherzo Fantastico. IV. Cadenza II per due violini. V. Piccola musica notturna. VI. Cadenza III per pianoforte. VII. Finale. ALBERTO GINASTERA. Serenata sobre los «Poemas de amor», de Neruda, Op. 42 (1974). I. Poetico. II. Fantastico. III. Drammatico. Violoncello: Aurora Nàtola. Baritono: Antonio Blancas. Grupo Koan Director: Julio Malaval. NOTAS AL PROGRAMA QUINTETO Para piano y cuarteto de cuerdas, Op. 29 El «Quinteto» Op. 29 me fue encargado por la señora Jeannette Arata de Erize, presidente del Mozarteum Argentino, con destino al Quinteto Chigiano de Siena, quien estrenó la obra ei 13 de abril de 1963 en el teatro La Fenice de Venecia durante el Festival de Música Contemporánea que se realizaba en dicha ciudad. En este «Quinteto», como lo señalaron algunos mu- sicólogos estudiosos de mi obra, se manifiestan cla- ramente algunas de mis preocupaciones más anhe- lantes en el campo de la creación musical: la elabo- ración de un lenguaje personal en su textura, la bús- queda de nuevas estructuras que se acomoden al idioma sonoro actual y la adaptación del discurso musical a un procedimiento de escritura basado en el máximo empleo de las posibilidades de los instru- mentos y en el realce del virtuosismo de los intérpre- tes. Los movimientos tradicionales de las obras de cá- mara que respondían a las exigencias de la música tonal están aquí reemplazados por cuatro estructuras que conservan el carácter del allegro, scherzo, ada- gio y final, pero cuya forma está dada por los proce- dimientos derivados de la técnica «post-serial». -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 128, 2008-2009

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 128th Season, 2008-2009 COMMUNITY CONCERT IX Sunday, March 29, at 3, at Granoff Music Center, Tufts University, Medford CHAMBER TEA V Friday, April 3, at 2:30 COMMUNITY CONCERT X Sunday, April 5, at 3, at Hernandez Cultural Center, Boston The free Community Concerts on March 29 and April 5 are generously supported by The Lowell Institute. CYNTHIA MEYERS, flute and piccolo ROBERT SHEENA, oboe and English horn THOMAS MARTIN, clarinet SUZANNE NELSEN, bassoon JONATHAN MENKIS, horn TIMOTHY GENIS, percussion (Piazzolla; Toussaint; D'Rivera "Afro") PIAZZOLLA Libertango (arr. Jeff Scott) MILHAUD "Sorocaba" and "Ipanema" from Saudades do Brasil, Opus 67 (arr. David Bussick) PIAZZOLLA Oblivion (arr. Jeff Scott) TOUSSAINT Mambo D'RIVERA Aires Tropicales 1. Alborada 2. Son 3. Wapango (arr. Jeff Scott /Tom Martin) 4. Habanera 5. Vals Venezolano 6. Afro 7. Contradanza Week 22 Astor Piazzolla (1921-92) Libertango and Oblivion Born in Mar del Plata, Argentina, Astor Piazzolla moved with his family to New York City in 1925, where (with one brief return to Argentina in 1930) they lived until 1936. He took up the bandoneon, the central instrument in the Ar- gentine tango, and also studied classical piano. Upon his return to Argentina he began to perform with tango orchestras, but also studied composition with the great Alberto Ginastera. He formed his first orchestra in 1946 but disbanded it as his music became more experimental. Piazzolla's music of the time shows the influence of Bartok and Stravinsky, but with some Argentine elements like the inclusion of two bandoneons in the orchestral work Buenos Aires.