Uses and Customs in Bolivia: Impacts of the Irrigation Law on Access to Water in the Cochabamba Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORICA. Vol. IX N9 2 1985 PROBANZA DE LOS INCAS

HISTORICA. Vol. IX N9 2 1985 PROBANZA DE LOS INCAS NIETOS DE CONQUISTADORES John Howland RoiWe Universidad de California - Berkeley La gran extensión que alcanzó el Tawantinsuyo fue el resulta do de las campañas conquistadoras de Thupa 'Inka Yupanki entre 1463 y 1493 aproximadamente. Los descendientes de Thupa 'Inka favorecieron la causa de Waskhar en la guerra civil de los incas (1531- 1532), motivo por el cual los generales de 'Ataw Wallpa mataron a los que lograron prender y quemaron el cuerpo del gran conquistador. Sobrevivieron algunos, principalmente niños, y en mayo de 1569 los de ellos que vivían en el Cusco se presentaron ante el Licenciado Juan Ayllón, teniente de corregidor, para solicitar se recibiera una información probando su ascendencia real y las conquistas de Thupa 'lnka. Acompañaron la solicitud con un interrogatorio y dos memo rias. Aprobada la solicitud, presentaron diez testigos que certificaron la veracidad de lo alegado. Los solicitantes no pidieron su traslado inmediatamente, sino dos años más tarde, en mayo de 1571, ante un nuevo corregidor, el Dr. Gabriel de Loartc. Sobrevino la intervención del virrey Francisco de Toledo y la destrucción definitiva del estado inca en 1572. Los interesados guardaron su probanza, y el documen to tuvo una modesta circulación entre sus descendientes. Apareció recientemente en 1984 entre los papeles del Archivo Departamental del Cusco. La probanza tuvo la finalidad de acreditar la calidad de los in teresados como descendientes de conquistadores incas, para con ella solicitar mercedes del rey de España, un concepto interesante en sí, sobre todo en una época en que existía todavía una resistencia inca en Vilcabamba. -

The Roadto DEVELOPMENT In

MUNICIPAL SUMMARY OF SOCIAL INDICATORS IN COCHABAMBA NATIONWIDE SUMMARY OF SOCIAL INDICATORS THE ROAD TO DEVELOPMENT IN Net primary 8th grade of primary Net secondary 4th grade of Institutional Map Extreme poverty Infant mortality Municipality school coverage completion rate school coverage secondary completion delivery coverage Indicator Bolivia Chuquisaca La Paz Cochabamba Oruro Potosí Tarija Santa Cruz Beni Pando Code incidence 2001 rate 2001 2008 2008 2008 rate 2008 2009 1 Primera Sección Cochabamba 7.8 109.6 94.3 73.7 76.8 52.8 95.4 Extreme poverty percentage (%) - 2001 40.4 61.5 42.4 39.0 46.3 66.7 32.8 25.1 41.0 34.7 2 Primera Sección Aiquile 76.5 87.0 58.7 39.9 40.0 85.9 65.8 Cochabamba 3 Segunda Sección Pasorapa 83.1 75.4 66.9 37.3 40.5 66.1 33.4 Net primary school coverage (%) - 2008 90.0 84.3 90.1 92.0 93.5 90.3 85.3 88.9 96.3 96.8 Newsletter on the Social Situation in the Department | 2011 4 Tercera Sección Omereque 77.0 72.1 55.5 19.8 21.2 68.2 57.2 Completion rate through Primera Sección Ayopaya (Villa de th 77.3 57.5 87.8 73.6 88.9 66.1 74.8 77.8 74.4 63.1 5 93.0 101.7 59.6 34.7 36.0 106.2 67.7 8 grade (%) - 2008 Independencia) CURRENT SITUATION The recent years have been a very important nificant improvement in social indicators. -

Water As More Than Commons Or Commodity: Understanding Water Management Practices in Yanque, Peru

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 12 | Issue 2 Brandshaug, M.K. 2019. Water as more than commons or commodity: Understanding water management practices in Yanque, Peru. Water Alternatives 12(2): 538-553 Water as More than Commons or Commodity: Understanding Water Management Practices in Yanque, Peru Malene K. Brandshaug Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Global warming, shrinking glaciers and water scarcity pose challenges to the governance of fresh water in Peru. On the one hand, Peruʼs water management regime and its legal framework allow for increased private involvement in water management, commercialisation and, ultimately, commodification of water. On the other hand, the state and its 2009 Water Resource Law emphasise that water is public property and a common good for its citizens. This article explores how this seeming paradox in Peruʼs water politics unfolds in the district of Yanque in the southern Peruvian Andes. Further, it seeks to challenge a commons/commodity binary found in water management debates and to move beyond the underlying hegemonic view of water as a resource. Through analysing state-initiated practices and practices of a more-than-human commoning – that is, practices not grounded in a human/nature divide, where water and other non-humans participate as sentient persons – the article argues that in Yanque many versions of water emerge through the heterogeneous practices that are entangled in water management. KEYWORDS: Water, water management, commodification, more-than-human commoning, uncommons, Andes, Peru INTRODUCTION At a community meeting in 2016, in the farming district of Yanque in the southern Peruvian Andes, the water users discussed their struggles with water access for their crops. -

(Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú

Indice Diagnostico Ambiental del Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopo-Salar de Coipasa (Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú Indice Executive Summary in English UNEP - División de Aguas Continentales Programa de al Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente GOBIERNO DE BOLIVIA GOBIERNO DEL PERU Comité Ad-Hoc de Transición de la Autoridad Autónoma Binacional del Sistema TDPS Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Departamento de Desarrollo Regional y Medio Ambiente Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos Washington, D.C., 1996 Paisaje del Lago Titicaca Fotografía de Newton V. Cordeiro Indice Prefacio Resumen ejecutivo http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (1 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Antecedentes y alcance Area del proyecto Aspectos climáticos e hidrológicos Uso del agua Contaminación del agua Desarrollo pesquero Relieve y erosión Suelos Desarrollo agrícola y pecuario Ecosistemas Desarrollo turístico Desarrollo minero e industrial Medio socioeconómico Marco jurídico y gestión institucional Propuesta de gestión ambiental Preparación del diagnóstico ambiental Executive summary Background and scope Project area Climate and hydrological features Water use Water pollution Fishery development Relief and erosion Soils Agricultural development Ecosystems Tourism development Mining and industrial development Socioeconomic environment Legal framework and institutional management Proposed approach to environmental management Preparation of the environmental assessment Introducción Antecedentes Objetivos Metodología Características generales del sistema TDPS http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (2 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Capítulo I. Descripción del medio natural 1. Clima 2. Geología y geomorfología 3. Capacidad de uso de los suelos 4. -

Water Footprint Assessment of Bananas Produced by Small Banana Farmers in Peru and Ecuador

Water footprint assessment of bananas produced by small banana farmers in Peru and Ecuador L. Clercx1, E. Zarate Torres2 and J.D. Kuiper3 1Technical Assistance for Sustainable Trade & Environment (TASTE Foundation), Koopliedenweg 10, 2991 LN Barendrecht, The Netherlands; 2Good Stuff International CH, Blankweg 16, 3072 Ostermundigen, Bern, Switzerland; 3Good Stuff International B.V., PO Box 1931, 5200 BX, s’-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands. Abstract In 2013, Good Stuff International (GSI) carried out a Water Footprint Assessment for the banana importer Agrofair and its foundation TASTE (Technical Assistance for Sustainable Trade & Environment) of banana production by small farmers in Peru and Ecuador, using the methodology of the Water Footprint Network (WFN). The objective was to investigate if the Water Footprint Assessment (WFA) can help define strategies to increase the sustainability of the water consumption of banana production and processing of smallholder banana producers in Peru and Ecuador. The average water footprint was 576 m3 t-1 in Ecuador and 599 m3 t-1 for Peru. This corresponds respectively to 11.0 and 11.4 m3 per standard 18.14 kg banana box. In both samples, approximately 1% of the blue water footprint corresponds to the washing, processing and packaging stage. The blue water footprint was 34 and 94% of the total, respectively for Ecuador and Peru. This shows a strong dependency on irrigation in Peru. The sustainability of the water footprint is questionable in both countries but especially in Peru. Paradoxically, the predominant irrigation practices in Peru imply a waste of water in a context of severe water scarcity. The key water footprint reduction strategy proposed was better and more frequent dosing of irrigation water. -

Pdf | 375.52 Kb

BOLIVIA• Inundaciones, Granizadas y Sequias 2012 Informe de Situación No.03/12 Fecha: 03/04/2012 Gobierno Autónomo Departamental de Cochabamba Este informe de situación es producido por el equipo de la Sala de Situación conformado por la Unidad de Gestión de Riesgos en el departamento, complementado con información de la Defensa Civil y los municipios afectados. Próximo informe de situación será emitido alrededor de 15.04.2012. I. PUNTOS DESTACADOS Desde el 19 de enero de 2012 a la fecha, los diferentes fenómenos, afectaron a 5189 Has. de cultivos. Para el periodo de este informe 8.266 familias resultaron afectadas, 4.075 familias damnificadas, 71 viviendas colapsadas, en 26 municipios del departamento de Cochabamba. Los municipios de Cercado, Colcapirhua, Quillacollo, Villa Tunari, Independencia, Tacopaya, Morochata y Sipe Sipe registran la mayor afectación por las intensas precipitaciones suscitadas en este periodo. Pese a las acciones de mitigación realizadas por Municipio de Pasorapa, debido al déficit hídrico solicito apoyo a la Gobernación para paliar los efectos de la sequia. A nivel municipal se emitieron 26 ordenanzas municipales de declaratoria de emergencia y/o desastre con el objetivo de proceder a la canalización de recursos departamentales. En consideración al marco jurídico el gobierno autónomo departamental de Cochabamba mediante ley departamental 159/ 2011-2012 del 23 de febrero de 2012 aprueba la LEY DECLARATORIA DE EMERGENCIA Y DESASTRE DEPARTAMENTAL POR LOS FENOMENOS DEL CAMBIO CLIMATICO EN EL DEPARTAMENTO DE COCHABAMBA. A la fecha la Gobernación atendió de manera conjunta con las instituciones que conforman el COED a 26 municipios afectados. Las autoridades comunales y municipales se encuentran realizando las evaluaciones de daños y análisis de necesidades de los municipios Toco, Aiquile, Sacabamba, Mizque y Santibáñez. -

We Arrived in Cochabamba and Were Again Very Graciouly Received By

REPORT GENERAL SURGERY MISSION TRIP February 22 – March 3, 2013 Cochabamba, Tiquipaya and Aiquile, Bolivia Dr. Gay Garrett and Dr. Gabe Pitta (in blue) and new local partner, Dr. Luis Herrera, performing laparoscopic surgery at Tiquipaya Hospital, one of three surgical sites during the 2013 GSMT. GOALS The annual General Surgery Mission Trip (GSMT) is a fundamental component of the Solidarity Bridge General Surgery Program, which offers surgeries on an ongoing basis performed by our Bolivian surgical partners. The Mission Trip has three primary goals: • To provide high-complexity surgeries to patients who do not have access to such medical treatment, both because they cannot afford it and, in particular, because the level or type of surgery is not yet readily available. • To monitor the performance and continue to upgrade the skills of previously-established Bolivian surgical, anesthesia, and other medical partners, and to evaluate and train new local partners. • To monitor, evaluate and fill equipment and supply needs to maintain and advance the program. 1 In addition, this trip included the third surgical team visit to the town of Aiquile as part of an agreement with Doctors Without Borders (MSF) to provide megacolon surgeries for chronic Chagas disease patients identified through MSF’s Chagas program in that region of Bolivia. PRIMARY ACTIVITIES and ACHIEVEMENTS The 2013 GSMT included four North American surgeons, five anesthesiologists, a gastroenterologist, and support personnel at three hospitals in Cochabamba, Tiquipaya and Aiquile. A total of 46 surgeries were performed: • 22 surgeries at the Instituto Gastroenterológico Boliviano Japonés in Cochabamba (known as the Gastro Hospital). -

Presupuesto De Inversión Pública Detalle Institucional

PRESUPUESTO DE INVERSIÓN PÚBLICA DETALLE INSTITUCIONAL Expresado en miles de Bolivianos 2016 INSTITUCION PGE % Part. Administración Central 35,154,544 80.13% Ministerios 6,900,221 15.73% 0015 Ministerio de Gobierno 5,758 0.01% 0016 Ministerio de Educación 122,107 0.28% 0025 Ministerio de la Presidencia 2,283,094 5.20% 0035 Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas Públicas 88,159 0.20% 0046 Ministerio de Salud 1,299,492 2.96% 0047 Ministerio de Desarrollo Rural y Tierras 451,658 1.03% 0051 Ministerio de Autonomía 1,349 0.00% 0052 Ministerio de Culturas y Turismo 82,519 0.19% 0066 Ministerio de Planificación del Desarrollo 12,159 0.03% 0070 Ministerio de Trabajo, Empleo y Previsión Social 17,230 0.04% 0076 Ministerio de Minería y Metalurgia 4,000 0.01% 0078 Ministerio de Hidrocarburos y Energía 901,036 2.05% 0081 Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Servicios y Vivienda 1,158,698 2.64% 0086 Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Agua 214,352 0.49% 0087 Ministerio de Comunicación 258,610 0.59% Entidades Descentralizadas 11,115,749 25.34% 0132 Servicio de Desarrollo de las Empresas Públicas Produtivas 657,803 1.50% 0150 Proyecto Sucre Ciudad Universitaria 5,989 0.01% 0163 Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos 5,286 0.01% 0201 Agencia para el Desarrollo de las Macroregiones y Zonas Fronterizas 33,700 0.08% 0203 Autoridad de Supervisión del Sistema Financiero 6,441 0.01% 0206 Instituto Nacional de Estadística 121,216 0.28% 0222 Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agropecuaria y Forestal 24,012 0.05% 0223 Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Forestal 7,101 0.02% 0225 Serv. -

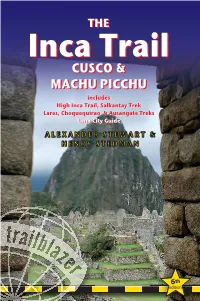

Machu Picchu Was Rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911

Inca-6 Back Cover-Q8__- 22/9/17 10:13 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Inca Trail High Inca Trail, Salkantay, Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks + Lima Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks Salkantay, High Inca Trail, THETHE 6 EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. Inca Trail They are particularly strong on mapping...’ Inca Trail THE SUNDAY TIMES CUSCOCUSCO && Lost to the jungle for centuries, the Inca city of Machu Picchu was rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911. It’s now probably MACHU PICCHU the most famous sight in South America – includesincludes and justifiably so. Perched high above the river on a knife-edge ridge, the ruins are High Inca Trail, Salkantay Trek Cusco & Machu Picchu truly spectacular. The best way to reach Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks them is on foot, following parts of the original paved Inca Trail over passes of Lima City Guide 4200m (13,500ft). © Henry Stedman ❏ Choosing and booking a trek – When Includes hiking options from ALEXANDER STEWART & to go; recommended agencies in Peru and two days to three weeks with abroad; porters, arrieros and guides 35 detailed hiking maps HENRY STEDMAN showing walking times, camp- ❏ Peru background – history, people, ing places & points of interest: food, festivals, flora & fauna ● Classic Inca Trail ● High Inca Trail ❏ – a reading of The Imperial Landscape ● Salkantay Trek Inca history in the Sacred Valley, by ● Choquequirao Trek explorer and historian, Hugh Thomson Plus – new for this edition: ❏ Lima & Cusco – hotels, -

Trilateral Cooperation Bolivia-Brasil-Germany

Trilateral Cooperation Bolivia-Brasil-Germany COTRIFOR—Innovation in Drought-resilient Forage Systems in the Mesothermal Valleys of Cochabamba, Bolivia Context • Actively steering project planning, implementation and evalu- ation, and providing feedback on the performance and contri- Bolivia is among the most biologically rich countries in the world. bution of the implementing institutions; With altitudes ranging from 130 to 6,542 meters, it has a wide variety of regions and ecological strata, which are home to a high • Making the logistical arrangements for the implementation of diversity of plants and animals. The arid zones of Bolivia are some planned activities, coordinating monitoring meetings and par- of the most important ecosystems, due to their high intrinsic va- ticipatory workshops, in addition to preparing dissemination lue as hubs of biological diversity and endemism. material for farmers; The arid zones of Bolivia cover about 40% of the national territory, The Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC) is responsible for coordi- being where the bulk of the population is in extreme poverty, nating the Brazilian contribution. The implementing institution for accounting for 36% of the rural population. In this region, a large this project is the Empresa Brasileira de Investigação Agropecuária percentage of the rural population is mainly dependent on agricul- (EMBRAPA), which is responsible for providing technical assistan- ture and livestock, which are highly vulnerable to rainfall, and ce in the following areas: have low levels of productivity and competitiveness. • Trainings on forage, ecological restoration and forage conser- The improvement of fodder systems in this region will simultane- ously affect improvement in these families' quality of life and de- vation; crease pressure on natural resources, especially water, which is • Provision of technical support material on the project's topics; very scarce in the project's area of operation. -

Midpacific Volume43 Issue1.Pdf

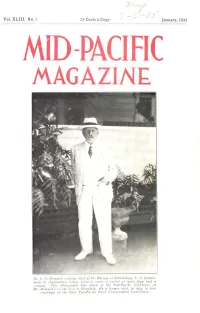

Vol. XLIII. No. 1 25 Cents a Copy January, 1932 MID-PACIFIC MAGAZINE Dr. L. 0. Howard, retiring chief of the Bureau of Entomology, U. S. Depart- ment of Agriculture, whose services cover a period of more than half a century. This photograph was taken at the Pan-Pacific Clubhouse on Dr. Howard's recent visit to Honolulu. On a former visit, in 1924, he was chairman of the First Pan-Pacific Food Conservation Conference. -W/r(4`d Indnal./L1LIRnrii RrARTIDLIRRTRRTinnoLu 4. t 04r filliii-ilartfir filaga3tur CONDUCTED BY ALEXANDER HUME FORD Volume XLIII Number 1 • CONTENTS FOR JANUARY, 1932 . 1 . 4, Scientific Problems of the Pineapple Industry - - - 3 4 By Dr. Royal N. Chapman 1 X' All About Bamboo 9 . Rice 15 1 L By Dr. F. G. Krauss el • i • Problems in Copra Industry 19 . • Irrigation in Peru 25 • By C. W. Sutton • . • • ! Some General Information on Panama 33 i By Rene C. Reynolds • r • );.,.. Cinchona, A Tree That Has Altered Maps - - - 41 • g 1• .1 .1 • Cinchona Culture in Java 43 . ri An Excursion to the Riu-Kiu Islands 49 1 • By P. J. Schmidt ,.4.. The Production and Marketing of Diatomaceous Earth - 55 By A. L. Lomax 1 59 l4 The Eel in Japan 5 I '. Frogs in Hawaii 61 . By E. H. Bryan, Jr. ■ 1 • Bulletin of the Pan-Pacific Union, New Series No. 143 - 65 :4. ICI. • Journal of the Pan-Pacific Research Institution, Vol. VII, No. 1. ., ,,,.._ agazine ,„; Gip fi: id-farifir n '-= Published monthly by ALEXANDER HUMS FORD, Pan-Pacific Club Building, Honolulu, T. -

Centros De Educación Alternativa – Cochabamba

CENTROS DE EDUCACIÓN ALTERNATIVA – COCHABAMBA DIRECTORES DISTRITO CENTRO DE EDUCACIÓN COD SIE NUMERO EDUCATIVO ALTERNATIVA AP. AP. PATERNO NOMBRE 1 NOMBRE 2 DE MATERNO CELULAR AIQUILE 80970088 OBISPADO DE AIQUILE JIMENEZ GUTIERREZ DELIA ANGELICA 72287473 AIQUILE 80970093 MARCELO QUIROGA SANTA CRUZ CADIMA COLQUE OMAR 74370437 ANZALDO 70950054 JESUS MARIA CHOQUE HEREDIA SILVIA EDITH 76932649 ARANI 80940033 ARANI A BERDUGUEZ CLAROS MARIA ESTHER 76477021 ARQUE 80930051 ARQUE LUNA ALVAREZ NELLY 63531410 ARQUE 80930078 SAN JUAN BAUTISTA CALLE VILLCA GERMANA 71418791 INDEPENDENCIA 80960094 CLAUDINA THEVENET CONDORI QUISPE ROLANDO 72394725 INDEPENDENCIA 80960115 INDEPENDENCIA ZUBIETA ALBERTO 67467699 CAPINOTA 80920048 CAPINOTA CASTELLON MENESES AURORA ISABEL 76996213 CHIMORE 50870050 CONIYURA CASTELLON MENESES AURORA ISABEL 76996213 CHIMORE 50870054 SAN JOSE OBRERO SANDOVAL RAMOS JAVIER 68508294 CLIZA 80910034 JORGE TRIGO ANDIA AGUILAR VARGAS JUAN 79755130 COCHABAMBA 1 80980493 27 DE MAYO CARRION SOTO MARIA LUZ 61099987 COCHABAMBA 1 80980321 ABAROA C PORTILLO ROJAS BLADIMIR PABLO 71953107 COCHABAMBA 1 80980489 AMERICANO A CAPUMA ARCE EGBERTO 71774712 COCHABAMBA 1 80980451 BENJAMIN IRIARTE ROJAS GUZMAN PEÑA MARTHA 69468625 COCHABAMBA 1 80980026 BERNARDINO BILBAO RIOJA VERA QUEZADA LUCIEN MERCEDES 79779574 COCHABAMBA 1 80980320 COCHABAMBA CHUQUIMIA MAYTA VICTOR ARIEL 79955345 COCHABAMBA 1 DAON BOSCO C TORREZ ROBLES NELLY CELIA 76963479 COCHABAMBA 1 80980488 DON BOSCO D MURIEL TOCOCARI ABDON WLDO 70797997 COCHABAMBA 1 80980443 EDMUNDO BOJANOWSKI