Violence in Jazz Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

A Transgender Journey in Three Acts a PROJECT SUBMITTED to THE

Changes in Time: A Transgender Journey in Three Acts A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ethan Bryce Boatner IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2012 © Ethan Bryce Boatner 2012 i For Carl and Garé, Josephine B, Jimmy, Timothy, Charles, Greg, Jan – and all the rest of you – for your confidence and unstinting support, from both EBBs. ii BAH! Kid talk! No man is poor who can to what he likes to do once in a while! Scrooge McDuck ~ Only a Poor Old Man iii CONTENTS Chapter By Way of Introduction: On Being and Becoming ..…………………………………………1 1 – There Have Always Been Transgenders–Haven’t There? …………………………….8 2 – The Nosology of Transgenderism, or, What’s Up, Doc? …….………...………….….17 3 – And the Word Was Transgender: Trans in Print, Film, Theatre ………………….….26 4 – The Child Is Father to the Man: Life As Realization ………….…………...……....….32 5 – Smell of the Greasepaint, Roar of the Crowd ……………………………...…….……43 6 – Curtain Call …………………………………………………………………....………… 49 7 – Program ..………………………..……………………………….……………...………..54 8 – Changes in Time ....………………………..…………………….………..….……........59 Wishes ……………………………….………………….……………...…………………60 Dresses …………………………………………………….…………………….….…….85 Changes ………………………………………………………….….………..…………107 9 – Works Cited …………………….………………………………………....…………….131 1 By Way of Introduction On Being and Becoming “I think you’re very brave,” said G as the date for my public play-reading approached. “Why?” I asked. “It takes guts to come out like that, putting all your personal things out in front of everybody,” he replied. “Oh no,” I assured him. “The first six decades took guts–this is a piece of cake.” In fact, I had not embarked on the University of Minnesota’s Master of Liberal Studies (MLS) program with the intention of writing plays. -

1 the Words December 2007 Over the Last 15 Years Or So I Have Been

Songbook version January 2008 The Words December 2007 Over the last 15 years or so I have been collecting lyrics to songs - mostly old-time country, bluegrass, cowboy, and old blues songs. I wanted to consolidate these lyrics into one big searchable file that I could use as a reference. I started with the Carter Family, Stanley Brothers, Flatt & Scruggs, Bill Monroe, and Uncle Dave Macon sections, which I had in separate documents, previously downloaded from the web over the last few years. I can’t remember where I got the Carter Family or Uncle Dave songs, but the rest were mostly from Bluegrasslyrics.com. I had the rest of the songs in a huge binder. Excluding those that were already in the existing sections, I searched the web for lyrics that were close to the version I had. Other useful websites: www.mudcat.org www.traditionalmusic.co.uk http://mywebpages.comcast.net/barb923/lyrics/i_C.htm www.cowboylyrics.com http://prewarblues.org/ (not so many lyrics, but a cool site) There is a rough Table of Contents at the start of the document, and a detailed Index at the end. I’d recommend using the Index if you are looking for something in particular, or use your search tool. (There is no reason why some of the song titles are in CAPS but they are mostly Carter Family songs). I haven’t been able to read every song, so there may be lyrics that are insensitive, especially in the Uncle Dave Macon section. I’m sorry if I missed them. -

2012 Hanne-Blank-Straight.Pdf

STRAIGHT THE SURPRISINGLY SHORT HISTORY OF HETEROSEXUALITY HANNE BLANK Beacon Press · Boston 2 For Malcolm 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Sexual Disorientation CHAPTER ONE The Love That Could Not Speak Its Name CHAPTER TWO Carnal Knowledge CHAPTER THREE Straight Science CHAPTER FOUR The Marrying Type CHAPTER FIVE What’s Love Got to Do with It? CHAPTER SIX The Pleasure Principle CHAPTER SEVEN Here There Be Dragons ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX 4 INTRODUCTION Sexual Disorientation Every time I go to the doctor, I end up questioning my sexual orientation. On some of its forms, the clinic I visit includes five little boxes, a small matter of demographic bookkeeping. Next to the boxes are the options “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual,” “transgender,” or “heterosexual.” You’re supposed to check one. You might not think this would pose a difficulty. I am a fairly garden-variety female human being, after all, and I am in a long-term monogamous relationship, well into our second decade together, with someone who has male genitalia. But does this make us, or our relationship, straight? This turns out to be a good question, because there is more to my relationship—and much, much more to heterosexuality—than easily meets the eye. There’s biology, for one thing. My partner was diagnosed male at birth because he was born with, and indeed still has, a fully functioning penis. But, as the ancient Romans used to say, barba non facit philosophum—a beard does not make one a philosopher. Neither does having a genital outie necessarily make one male. Indeed, of the two sex chromosomes—XY—which would be found in the genes of a typical male, and XX, which is the hallmark of the genetically typical female—my partner’s DNA has all three: XXY, a pattern that is simultaneously male, female, and neither. -

Music by Women TABLE of CONTENTS

Music by Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Ordering Information 2 Folk/Singer-Songwriter 58 Ladyslipper On-Line! * Ladyslipper Listen Line 4 Country 64 New & Recent Additions 5 Jazz 65 Cassette Madness Sale 17 Gospel 66 Cards * Posters * Grabbags 17 Blues 67 Classical 18 R&B 67 Global 21 Cabaret 68 Celtic * British Isles 21 Soundtracks 68 European 27 Acappella 69 Latin American 28 Choral 70 Asian/Pacific 30 Dance 72 Arabic/Middle Eastern 31 "Mehn's Music" 73 Jewish 31 Comedy 76 African 32 Spoken 77 African Heritage 34 Babyslipper Catalog 77 Native American 35 Videos 79 Drumming/Percussion 37 Songbooks * T-Shirts 83 Women's Spirituality * New Age 39 Books 84 Women's Music * Feminist * Lesbian 46 Free Gifts * Credits * Mailing List * E-Mail List 85 Alternative 54 Order Blank 86 Rock/Pop 56 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, 3205 Hillsborough Road. Durham NC 27705 USA PHONE ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat 10-6 Eastern Time) ORDERING INFO FAX ORDERS: 800-577-7892 INFORMATION: 919-383-8773 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.ladyslipper.org PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available: CD = compact disc, CS = cassette. Some schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives recordings are available only on CD or only on cassette, Ladyslipper, Inc. -

CD 64 Motion Poet Peter Erskine Erskoman (P. Erskine) Not a Word (P

Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 5/23/2011 JAZZ CD 64 Motion Poet Peter Erskine Erskoman (P. Erskine) Not a Word (P. Erskine) Hero with a Thousand Faces (V. Mendoza) Dream Clock (J. Zawinul) Exit up Right (P. Erskine) A New Regalia (V. Mendoza) Boulez (V. Mendoza) The Mystery Man (B. Mintzer) In Walked Maya (P. Erskine) CD 65 Real Life Hits Gary Burton Quartet Syndrome (Carla Bley) The Beatles (John Scofield) Fleurette Africaine (Duke Ellington) Ladies in Mercedes (Steve Swallow) Real Life Hits (Carla Bley) I Need You Here (Makoto Ozone) Ivanushka Durachok (German Lukyanov) CD 66 Tachoir Vision (Marlene Tachoir) Jerry Tachoir The Woods The Trace Erica’s Dream Township Square Ville de la Baie Root 5th South Infraction Gibbiance A Child’s Game CD 68 All Pass By (Bill Molenhof) Bill Molenhof PB Island Stretch Motorcycle Boys All Pass By New York Showtune Precision An American Sound Wave Motion CD 69 In Any Language Arthur Lipner & The Any Language Band Some Uptown Hip-Hop (Arthur Lipner) Mr. Bubble (Lipner) In Any Language (Lipner) Reflection (Lipner) Second Wind (Lipner) City Soca (Lipner) Pramantha (Jack DeSalvo) Free Ride (Lipner) CD 70 Ten Degrees North 2 Dave Samuels White Nile (Dave Samuels) Ten Degrees North (Samuels) Real World (Julia Fernandez) Para Pastorius (Alex Acuna) Rendezvous (Samuels) Ivory Coast (Samuels) Walking on the Moon (Sting) Freetown (Samuels) Angel Falls (Samuels) Footpath (Samuels) CD 71 Marian McPartland Plays the Music of Mary Lou Williams Marian McPartland, piano Scratchin’ in the Gravel Lonely Moments What’s Your Story, Morning Glory? Easy Blues Threnody (A Lament) It’s a Grand Night for Swingin’ In the Land of Oo Bla Dee Dirge Blues Koolbonga Walkin’ and Swingin’ Cloudy My Blue Heaven Mary’s Waltz St. -

Billy Tipton's Life As a Passing Woman by Danielle

Essay Award Winner 2002 The Man Who Played Well for a Woman: Billy Tipton’s Life as a Passing Woman by Danielle Picard Billy Tipton performed in a number of jazz and swing bands from the early 1930s onward as a vocalist and pianist, and according to a bandmate from the early days of Tipton’s career, “Billy was a fair sax man too, played very well for a woman.”[i][1] Some of the members of Tipton’s various bands, as well as some of the women who were considered his wives, never knew the secret revealed in this comment. Many of the people who knew and loved Tipton only learned on the occasion of his death in 1989 that he had been born female.[ii][2] Tipton is one of a large number of women in history who are now called “passing women” -- women who lived much of their lives as men.[iii][3] As in Billy’s case, the birth sex of these individuals was often a secret revealed only when they died. The lives of these women and of Billy Tipton in particular raise many questions about identity, gender, and sexuality, and these questions are not easily answered. Some historians have claimed Tipton and passing women in general as part of lesbian history while others see them as part of transsexual or transgender history; ultimately, it is impossible to determine which categorization is correct. Dorothy Lucille Tipton was born on December 29, 1914, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; BillyLee Tipton died in Spokane, Washington, on January 21, 1989. -

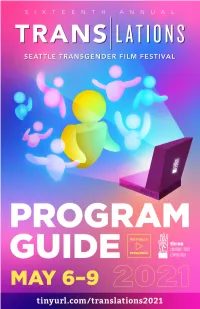

2021Translations-Program.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME LETTER . .. 3 OPENING NIGHT FILM . 4 CLOSING NIGHT FILM . 5 FEATURES . 7–12 SHORTS . 14–22 EVENTS . 24–25 WELCOME LEttER WELCOME TO THE 16TH ANNUAL TRANSLATIONS! It is our great privilege to co-program the 16th annual Seattle Translations Festival, one of only ten festivals of its kind in the world. After years of elevating the voices of people who are rarely heard, it can feel like the change we need to bring about has arrived, particularly here in the openly liberal space of the Pacific Northwest. But as we all know, there is much work to be done. As we finalize our program, there are currently almost ninety pieces of anti-trans legislation being proposed across the US, and the horrific murder of trans folx, especially black trans women and trans women of color, occurs at alarming rates. While our struggles are not the same as in Brazil or Ukraine, where government sanctioned annihilation of trans and queer identified folx happens every day, it remains true that many of us here and around the world desperately need to know we are not alone. It is indeed a powerful act to see ourselves on screen, to tell our own stories, and to exist in community with each other. This is the work we do. For that, we are humbled and grateful. In the midst of so much darkness, we invite you to spend some time in the (spot)light and celebrate trans lives with us. We look forward to bringing you great films from around the world and to interacting with you online. -

Cashbox Pands in Publishing • • Atlantic Sees Confab Sales Peak** 1St Buddah Meet

' Commonwealth United’s 2-Part Blueprint: Buy Labels & Publishers ••• Massler Sets Unit For June 22 1968 Kiddie Film ™ ' Features * * * Artists Hit • * * Sound-A-Like Jingl Mercury Ex- iff CashBox pands In Publishing • • Atlantic Sees Confab Sales Peak** 1st Buddah Meet Equals ‘ Begins Pg. 51 RICHARD HARRIS: HE FOUND THE RECIPE Int’l. Section Take a great lyric with a strong beat. Add a voice and style with magic in it. Play it to the saturation level on good music stations Then if it’s really got it, the Top-40 play starts and it starts climbingthe singles charts and selling like a hit. And that’s exactly what Andy’s got with his new single.. «, HONEY Sweet Memories4-44527 ANDY WILLIAMS INCLUDING: THEME FROM "VALLEY OF ^ THE DOLLS" ^ BYTHETIME [A I GETTO PHOENIX ! SCARBOROUGH FAIR LOVE IS BLUE UP UPAND AWAY t THE IMPOSSIBLE * DREAM if His new album has all that Williams magic too. Andy Williams on COLUMBIA RECORDS® *Also available fn A-LikKafia 8-track stereo tape cartridges : VOL. XXIX—Number 47/June 22, 1968 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone: JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box. N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Assoc. Editor DANIEL BOTTSTEIN JOHN KLEIN MARV GOODMAN EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI When Tragedy Cries (hit ANTHONY LANZETTA ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER New York For 'Affirmative'Musif BILL STUPER New York HARVEY GELLER Hollywood WOODY HARDING Art Director COIN MACHINES & VENDING ED ADLUM General Manager BEN JONES Asst. -

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 131 SPRING 2014 CURTIS STIGERS UK £3.25 CONTENTS CURTIS STIGERS (PAGE 10) THE AMERICAN SINGER/SONGWRITER/SAXOPHONIST TALKS OF HIS VARIED CAREER IN MUSIC AHEAD OF THE RELEASE OF HIS LATEST CONCORD ALBUM, HOORAY FOR LOVE AND HIS APPEARANCES AT CHELTENHAM AND RONNIE SCOTT'S. 4 NEWS 5 UPCOMING EVENTS 7 LETTERS 8 HAPPY 100TH BIRTHDAY! SCOTT YANOW on jazz musicians born in 1914. 12 RETRIEVING THE MEMORIES Singer/collector/producer CHRIS ELLIS SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG looks back. THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED 15 MIDEM (PART 2) DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY £17.50* 16 JAZZ FESTIVALS Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your 20 JAZZ ARCHIVE/COMPETITIONS payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: 21 CD REVIEWS EU £20.50 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £24.50 Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC 29 BOOK REVIEWS Please send to: JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 BBC YOUNG MUSICIAN JAZZ AWARD Fax: 0121 454 9996 On March 8 the final of the first BBC Young Musician Jazz Award took place at the Email: [email protected] Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. The five finalists were three saxophonists Web: www.jazzrag.com (Sean Payne, Tom Smith and Alexander Bone), a trumpeter, Jake Labazzi, and a double bassist, Publisher / editor: Jim Simpson Freddie Jensen, all aged between 13 and 18. -

L/Trrw\Ilrirec MECHANICS

L/Trrw\ILrirec MECHANICS 1.-LEE--1-1EL-2 CLASS ACT JBL L7 SPEAKER L=;_(.2LIN_LILJL--2 WE PICK THE BEST OF SEVEN L2 1NON, JVC, L2-LONEER, SAN US $2.95 UK £1.95 CAN $3.50 11,1[01. o I iIII I 2(1()CA.Z.;1) THE SOUND OF PURE GENIUS. It is most evident in a passion for details. The subtle refinements that elevate genius beyond that which is merely exceptional To honor this ability in gifted young musicians, Sony has created the "ES Award For Musical Excellence," in conjunction with The Juilliard School. To reproduce, with equal passion, the glorious details of music, we have created the Elevated Standard series of ultra -fidelity components. For a listening experience you will find truly prodigious, call 1-800-828-1380 for information. ©1992 Sony Corporation of Arnenca All rights reserved. Sony s a Trademark of Sony. DECEMBER 1992 A/V Receivers, page 46 Peter Asher, page 60 FEATURES A/V RECEIVER ROUNDUP Leonard Feldman 46 THE MECHANICS OF SONY'S MINIDISC: BEYOND THE CADDY Leonard Feldman 56 THE AUDIO INTERVIEW: PETER ASHER Ted Fox 60 1992 ANNUAL INDEX 176 EQUIPMENT PROFILES NOBIS CANTABILE AMPLIFIER Bascom H. King 72 YAMAHA CDC -835 CD CHANGER Leonard Feldman 103 AUDIX SCX-ONE STUDIO MIKE SYSTEM Jon R. Sank 108 JBL L7 SPEAKER D. B. Keele, Jr. 114 AURICLE: PIONEER ELITE PD -65 CD PLAYER Leonard Feldman 126 AURICLE: MOBILE FIDELITY SOUND LAB ULTRAMP PREAMP AND AMP Anthony H. Cordesman 130 MUSIC REVIEWS CLASSICAL RECORDINGS 138 ROCK/POP RECORDINGS 148MiniDisc, page 56 JAZZ & BLUES 160 DEPARTMENTS FAST FORE -WORD Eugene Pitts III 4 SIGNALS & NOISE 6 TAPE GUIDE Herman Burstein 11 AUDIOCLINIC Joseph Giovanelli 16 WHAT'S NEW 22 BEHIND THE SCENES Bert Whyte 33 CURRENTS John Eargle 36 ROADSIGNS Ivan Berger 40 THE BOOKSHELF 134 The Cover Equipment: Nobis Cantabile amplifier The Cover Photographer: ©Michael Groen reuda Audio Publishing, Editorial, and Advertising Offices, Bureau 1633 Broadway, New York, N.Y. -

Narratives of Selfhood, Embodied Identities, And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Musical Performance and Trans Identity: Narratives of Selfhood, Embodied Identities, and Musicking A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Randy Mark Drake Committee in charge: Professor Timothy J. Cooley, Chair Professor David Novak Professor Mireille Miller-Young Professor George Lipsitz June 2018 The dissertation of Randy Mark Drake is approved. _____________________________________________ David Novak _____________________________________________ Mireille Miller-Young ____________________________________________________________ George Lipsitz _____________________________________________ Timothy J. Cooley, Committee Chair May 2018 Musical Performance and Trans Identity: Narratives of Selfhood, Embodied Identities, and Musicking Copyright © 2018 by Randy Mark Drake iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge Timothy Cooley, the chair of this dissertation and my advisor, for his gifts of guidance and his ability to encourage all of my academic endeavors. Tim has a passion for ethnomusicology, teaching, and writing, and he enjoys sharing his knowledge in ways that inspired me. He was always interested in my work and my performances. I am grateful for his gentle nudging and prodding regarding my writing. My first year at UCSB was also the beginning of a deep engagement with academic writing and thinking, and I had much to learn. Expanding my research boundaries was made simpler and more stimulating thanks to his consistent support and encouragement. I thank Tim for his mentorship, compassion, and kindness. David Novak never ceased amazing me with his intellectual curiosity and probing questions when it came to my own work. His dissertation workshop kept me focused on my research problems, and his tenacity in questioning those problems contributed greatly to my intellectual growth.