THE COLLECTED ESSAYS of ST. GEORGE TUCKER Edited, With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

Commandant of the Marine Corps Approved a Change in the Words of the Fourth Line, First Verse, to Read, “In Air, on Land, and Sea.” Former Gunnery Sergeant H

144278_LE_I_Student_Textbook_Cover .indd Letter V 8/6/19 5:32 AM LE-I TABLE OF CONTENTS Leadership Leadership Defined ....................................................................................................................................... 1 The Leader Within ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Leadership Primary and Secondary Objectives .......................................................................................... 11 Ethics, Morals, Values ................................................................................................................................ 15 Marine Corps’ Core Values ........................................................................................................................ 21 Using Introspection to Develop Leadership Traits ..................................................................................... 27 Military Leadership Traits .......................................................................................................................... 31 The 11 Leadership Principals ...................................................................................................................... 41 Citizenship Defining Patriotism ..................................................................................................................................... 47 Rights, Responsibilities, and Privileges ..................................................................................................... -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Catalogue to the Number Or Address Below

CARVELL’S AUCTIONS New Zealand’s Specialist Firearms Auction House AUCTION 40 SUNDAY NOVEMBER 21st 2010 TO BE HELD AT THE HOLIDAY INN HOTEL AUCKLAND AIRPORT Viewing 8.30am - 10.30am Auction Commencing 10.30am FRONT COVER: Lot 179 - James Purdey Double Flintlock Fowling Piece. Lot 298 - Double Flintlock Turnover Pistol circa 1690 Lot 179 - James Purdey Double Flintlock Fowling Piece CARVELL’S AUCTIONS PRESENT OUR 20th ANNIVERSARY YEAR 40th AUCTION SALE TO BE HELD AT THE HOLIDAY INN AIRPORT HOTEL (formerly the Airport Travel lodge) CORNER OF KIRKBRIDE AND ASCOT ROADS AUCKLAND AIRPORT SUNDAY NOVEMBER 21st 2010 VIEWING FROM 8.30 -10.30 AM ON THE DAY, AUCTION COMMENCES AT 10.30 AM CARVELL’S AUCTIONS 553 Great South Road, Penrose 1061 Auckland New Zealand Phone +649 - 579-3771 Fax +649 - 537-1629 Send postal bids and payments to: Box 112313 Penrose 1642 www.gunauction.co.nz NOTES We will have an arms officer in attendance for your convenience to arrange permits. * Pistol Club shooters – If you wish to uplift a pistol on your B license at the auction you will have to bring with you a “pinky” form from your pistol club secretary. Otherwise you can arrange to pick up the pistol at a later date We will have EFTPOS for your convenience. We accept Visa and Mastercard – 3% surcharge will apply for credit cards. Sorry we do not accept American Express. Please bring gun bags and/or lock boxes for transport of firearms from the venue. POSTAL BIDDERS We guarantee to get your lots at the lowest possible price having regard to the next highest postal bid, bidding of the floor and any reserves. -

NCO Sword Manual

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS Marine Corps University Corporals Noncommissioned Officers Program CPL 0103 Jan 99 STUDENT HANDOUT Marine NCO Sword Manual LEARNING OBJECTIVES: a. TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVE: Given a training site, a Marine NCO sword, the appropriate accessories, and with the aid of references, execute the sword manual per the reference. (CPL 3.3) b. ENABLING LEARNING OBJECTIVES (CE): Without the aid of but per the references, identify the following: (1) The general rules of the NCO sword manual. (CPL 3.3a) (2) The nomenclature of the NCO sword. (CPL 3.3b) c. ENABLING LEARNING OBJECTIVES (PE): Given a training site, a Marine NCO sword, appropriate accessories, and without the aid of but per the references, execute the following movements: (1) Draw sword. (CPL 3.3c) (2) Order sword. (CPL 3.3d) (3) Carry sword. (CPL 3.3e) (4) Present sword. (CPL 3.3f) (5) Carriage while marching. (CPL 3.3g) (6) Rest with the sword. (CPL 3.3h) (7) Return sword. (CPL 3.3i) OUTLINE 1. GENERAL RULES AND NOMENCLATURE OF THE NCO SWORD: a. History of the Sword: After the Barbary Pirates War, Marine officers started carrying the Mameluke Sword. In 1858, the Marine Corps discontinued the Mameluke sword and adopted the 1858 Cavalry Sword. However, this was not a popular decision and during the Civil War, officers reverted back to the Mameluke Sword. For centuries, the sword has been a symbol of leadership and authority. But it had always been an officer’s weapon. When the Commandant gave the Mameluke Sword back to the officers, he decided to present the 1858 Cavalry Sword 0103H-1 (to become known as the NCO Sword) to Marine NCO’s in recognition of the part they play in leading Marines in combat. -

LE II Student Textbook.Pdf

144279_LE_II_Student_Textbook_Cover.indd Letter V 8/6/19 5:30 AM LE-II TABLE OF CONTENTS Leadership Leadership Primary and Secondary Objectives ............................................................................................ 1 The 11 Leadership Principals ........................................................................................................................ 5 Authority, Responsibility, and Accountability ........................................................................................... 11 The Role of the NCO .................................................................................................................................. 15 The Role of an Officer ................................................................................................................................ 29 Motivational Principles and Techniques ..................................................................................................... 33 Maintaining High Morale ........................................................................................................................... 39 Marine Discipline ........................................................................................................................................ 43 Individual and Team Training..................................................................................................................... 47 Proficiency Defined ................................................................................................................................... -

Two Day Militaria, Collectors & Sporting Sale

Two Day Militaria, Collectors & Sporting Sale Thursday 08 April 2010 11:00 Lawrences of Crewkerne South Street Crewkerne Somerset TA18 8AB Lawrences of Crewkerne (Two Day Militaria, Collectors & Sporting Sale) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 A 1750 PERIOD CAVALRY SWORD. A Cavalry Sword similar AN ABORIGINAL BOOMERANG. Shaped hardwood in detail to the 1742 Pattern with loop and guard altered from Boomerang of classical form, 24.5" overall length. original issue. 38.25" blade with small and larger fullers. Brass Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 hilt with leather grip wrapped in wire, 44.3/4" overall length. Estimate: £500.00 - £600.00 Lot: 2 A GERMAN PARADE BAYONET. Complete with scabbard and Lot: 11 brown frog, by P & A with sword hilt protruding from an A GEORGIAN NAVAL OFFICERS FIGHTING SWORD. Stirrup inverted triangle, Solingen inside. Plated 9.75" clean blade with hilt with lions head pommel, black wooden grip. Langets have red felt in bayonet slide, reverse swept quillion. Also a modern fouled anchor devices, one drilled for a locking pin. 28" curved Gaucho knife by an Argentinian maker with decorative single-edged blade, with large fuller from the hilt to almost the scabbard of horse and cow heads tip. Probably for a naval officer in the rank of Lieutenant, a Estimate: £40.00 - £50.00 private purchase fighting sword, C1790's. Estimate: £250.00 - £300.00 Lot: 3 A W W 11 GERMAN CAST PLAQUE. 12.375" wide by 14.5" Lot: 12 high with Eagle and Landrat (Magistrate) below in red and black A GEORGIAN NAVAL DIRK. -

Early Marine Corps Swords

cureton_110_133 9/29/06 3:14 PM Page 110 Early Marine Corps Swords Dr. Charles Cureton The subject of early Marine Corps swords is so shrouded in myth that it has blinded historians and collectors as to their actual history to this day. Every Marine recruit is taught that the officer’s Mameluke came into use with the presentation of a jeweled Mameluke saber to First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon by Hamet Karamanli after the legendary campaign against Derna in 1805. The story goes that the sword was so popular was this sword that every Marine officer had to have one. The style consequently came into widespread use, so much so that American Mameluke sabers that predate the reg- ulation 1826 model are considered by historians and collec- tors to have Marine Corps association or are rationalized as being unofficial deviations from the official pattern, the latter a direct reflection of our independent American spirit. United States and the known history of Presley O’Bannon Admittedly, the Mameluke saber was and is an exotic having carried one makes it easy for us to want every and attractive design (Figure 1). Its relative rarity in the Mameluke to be Marine Corps. It also helps us in our igno- rance that historians do not know much about the early Marine uniforms either, because a study of the uniform in photographs, portraits, and contemporaneous illustrations provides helpful hints as to the pattern of the actual swords being carried during the 1798 through 1875 period. Our understanding of the patterns of swords carried by musicians and noncommissioned officers is also mistaken. -

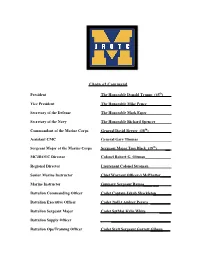

Chain of Command President the Honorable Donald

Chain of Command President The Honorable Donald Trump (45th) Vice President The Honorable Mike Pence Secretary of the Defense The Honorable Mark Esper Secretary of the Navy The Honorable Richard Spencer Commandant of the Marine Corps General David Berger (38th) Assistant CMC General Gary Thomas Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Sergeant Major Troy Black_(19th) MCJROTC Director Colonel Robert G. Oltman_____________ Regional Director Lieutenant Colonel Stroman Senior Marine Instructor Chief Warrant Officer-3 McPhatter Marine Instructor Gunnery Sergeant Ramos Battalion Commanding Officer Cadet Captain Jakob Shackleton Battalion Executive Officer Cadet 2ndLt Audrey Perera Battalion Sergeant Major Cadet SgtMaj Kylie White Battalion Supply Officer Battalion Ops/Training Officer Cadet Staff Sergeant Garrett Gibson Definition of Leadership Leadership - is the ability to influence, lead, or guide others to accomplish a mission in the manner desired by providing purpose, direction, and motivation. General Orders 1. To take charge of this post and all government property in view. 2. To walk my post in a military manner keeping always on the alert and observing everything that takes place within sight or hearing. 3. To report all violations of orders I am instructed to enforce. 4. To repeat all calls from posts more distant from the guardhouse than my own. 5. To quit my post only when properly relieved. 6. To receive, obey, and pass on to the sentry who relieves me all orders from the commanding officer, officer of the day, officers and non-commissioned officers of the guard only. 7. To talk to no one except in the line of duty. 8. -

The Auction Will Take Place at 9 A.M. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 3Rd May 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia

The Auction will take place at 9 a.m. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 3rd May 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia. The auction will be an internet, phone bid & absentee bid auction only, this being due to the regulations relating to the current COVID-19 pandemic. This will mean there will be no public attendance to view or bid on the day of the auction. We will be anticipating a large number of phone and absentee bids, so please do request these in good time, so that we may be able to assist you with your bidding requirements. Viewing of lots will take place between 27th April to 2nd May 9am to 4pm with the auction taking place at 9am and finishing around 5:00pm. Photos of each lot can be viewed via our ‘Auction’ tab of our website www.jbmilitaryantiques.com.au. Onsite registration will take place on onsite in during regular business hours, via email using a registered credit card or via internet auction portal. Bids will only be accepted from registered bidders. All telephone and absentee bids need to be received 3 days prior to the auction. Online registration is via www.the-saleroom.com & www.invaluable.com. All prices are listed in Australian Dollars. The buyer’s premium onsite, telephone & absentee bidding is 18%, with internet bidding at 21% + A.B.P. All lots are guaranteed authentic and come with a 90-day inspection/return period. All lots are deemed ‘inspected’ for any faults or defects based on the full description and photographs provided both electronically and via the pre-sale viewing, with lots sold without warranty in this regard. -

Australian Arms Auctions Pty. Ltd. BUYER’S TERMS & CONDITIONS of BUSINESS

Australian Arms Auctions Auctions Arms Australian 110 111 342 347 434 Auction No. 44 May 2nd & 3rd, 2015 3rd, & 2nd May 44 No. Auction Australian Arms Auctions Auction No. 44 May 2nd & 3rd, 2015 Melbourne 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 63 64 65 66 67 68 Australian Arms Auctions Pty Ltd May Auction No.44 Saturday 2nd May at 6.00 pm & Sunday 3rd May 2015 at 10 am VIEWING: Saturday 12 noon to 5 pm & Sunday 8 am – 10 am Eley Park Community Centre 87 Eley Road, Blackburn South, Victoria - Melways Ref: 61-H5 Auctioneer: Eero Pupedis www. . 1 U.S. N.R.A. grading of conditions apply. L/R = Licence required in the State of Victoria. ALL ESTIMATES IN AUSTRALIAN DOLLARS. 1 E.M. REILLY & CO U/O PERCUSSION BELT PISTOL: 60 Cal; 153mm (5") rnd barrels marked E.M. REILLY $600 - 800 OXFORD STREET LONDON, with captive rod; f. bores; plain borderline frame with elephant hammer to rhs; slight wear to profiles & address; soft grey finish to all metal; f to g plain stock with even wear, vacant silver escutcheon to wrist, lanyard ring to butt; missing belt hook o/w, gwo & f to g cond; would grade up. C.1860. #007853 L/R 2 ENGLISH PERCUSSION PEPPERBOX PISTOL: 36 Cal; 6 shot; 76mm (3") barrel cluster struck with Birmingham $400 - 500 proofs; foliate engraved iron frame with t/guard; slight wear to profiles & engraving; silver grey patchy finish to all metal; g. chequered walnut grips; wo & f to g cond. C.1860. -

Iron, Steel and Swords Script - Page 1

Sword Types Giving a short list of sword types seems to be easy. Well - it isn't. For one thing, it will never end because every culture / civilization or language group had and has plenty of sword types and words for them, most of them unknown outside that culture / civilization or language group, thank God. But some of these words made it to other groups already in the past, and more and more outlandish denominations make it into English or German right now. Unfortunately, the precise meaning, if it was known at all, may get lost in the process. Contrariwise, one and the same word might have different meanings here or there or then and now. Not to mention that there is no 1 : 1 correlation between translations from language to language. The English "broadsword" translates properly to a German "Korbschwert" (=basket sword). The direct translation would be "Breitschwert". This term does exist in German - but it denotes something quite different from a "broadsword". Only one thing seems to be certain: any short definition of some term, no matter which one, will bring in protests from some camp of believers out there. So let me state on the outset: whatever I write further down, my heart isn't in it. Correct me if you like. I'll go along with you - until the next correction comes in. Basics My own interest is not so much about the name associated with a particular type of sword but about its metallography. Since correlating sword types to metallography is mostly not a sensible thing to do, my next question is why some particular kind of sword existed at all? The user had always access to or at least some knowledge of some other types.