Status, Habitats and Conservation of the Dartford Warbler in England C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Literature Review of Urban Effects on Lowland Heaths and Their Wildlife

Report Number 623 A literature review of urban effects on lowland heaths and their wildlife English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Number 623 A literature review of urban effects on lowland heaths and their wildlife J C Underhill-Day RSPB, Syldata Arne, Wareham Dorset BH20 5BJ Telephone: 01929 550969 email: [email protected] You may reproduce as many additional copies of this report as you like, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with English Nature, Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA ISSN 0967-876X © Copyright English Nature 2005 Executive summary Introduction Heather clad lowland heath developed on light, freely draining, acid soils following prehistoric woodland clearance, and down the centuries, has been kept open by grazing, burning and cutting. As the economic value of these uses declined, considerable areas of heath were lost to agriculture, forestry, housing, roads, mineral working and other uses, and today, much of what is left is adjacent to built up areas, especially in Dorset. These lowland heathland fragments can be found across much of southern England on suitable soils. Much of the research on heathlands over the last twenty years has concentrated on the Dorset heaths, which are now almost all SSSIs and mostly within the Dorset Heathland SPA. While this report reflects the bias in the literature towards work in Dorset, the results have wide applicability to urban heathlands that are accessed by the surrounding urban populations for amenity and recreation whether in Dorset or elsewhere. This urban public access places considerable pressures on the heaths, for example through disturbance, wild fires, trampling, predation by domestic pets, pollution and enrichment. -

Sylvia Undata

Sylvia undata -- (Boddaert, 1783) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- SYLVIIDAE Common names: Dartford Warbler; European Red List Assessment European Red List Status NT -- Near Threatened, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Near Threatened (NT) EU27 regional assessment: Near Threatened (NT) This warbler is undergoing rapid population declines in Spain, which holds c.69% of the European and EU27 populations, but apparent increases in the second largest population, in Portugal, mean that overall declines have been moderately rapid. It is therefore classified as Near Threatened in both Europe and the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Andorra; France; Italy; Malta; Portugal; Spain; United Kingdom; Gibraltar (to UK) Vagrant: Belgium; Croatia; Czech Republic; Germany; Greece; Ireland, Rep. of; Montenegro; Netherlands; Serbia; Sweden; Switzerland; Turkey Population The European population is estimated at 646,000-1,480,000 pairs, which equates to 1,290,000-2,970,000 mature individuals. The entire population is found in the EU27. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend In Europe and the EU27 the population size is estimated to be decreasing at a rate approaching 30% in 12.3 years (three generations). For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Habitats and Ecology It favours dense, homogeneous scrub, garrigue and low maquis c. 0.5–1.5 m in height and dominated by species such as Ulex, Erica, Rosmarinus, Genista, Cistus and Quercus coccifera. -

Are Bird Communities Structured by Arthropod Availability?

Revista Catalana d’Ornitologia 21:17-28, 2005 Post-fire dynamics in Mediterranean shrublands: are bird communities structured by arthropod availability? Sergi Herrando, Lluís Brotons & Santiago Llacuna The relationship between arthropod availability and bird energy requirements was studied in Mediterranean shrublands. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that food availability is a possible constraint in the recovery of bird communities in post-fire dynamics. We used the sweep-net sampling method to collect arthropods, and the point-census method to assess bird abundance. The censuses were carried out during the breeding and wintering seasons in a fire-free zone and in two burned zones (one burned four years before the fieldwork, the other 16 years before it). During the breeding season, we found a positive association between arthropod availability and bird requirements in all three zones. However, compared with the other two zones, the recently burned zone contained fewer birds than expected, based on arthropod availability. Thus, it seems that birds exerted significantly lower predation pressure on arthropod populations in this zone than in the other two zones, which resembled each other in this parameter. These results suggest that arthropod availability does not constrain breeding-bird numbers soon after fire; however, it could do so in later successional stages. During winter, when the studied bird species also feed on fleshy-fruits, there were no conclusive associations between arthropods and birds. Key words: arthropod availability, bird community, predation pressure, post-fire succession, burned zones, Mediterranean shrublands. Sergi Herrando, Institut Català d’Ornitologia, Museu de Ciències Naturals, Passeig Picasso s/n, 08003 Barcelona. -

Is the Sardinian Warbler Sylvia Melanocephala Displacing the Endemic Cyprus Warbler S

Is the Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala displacing the endemic Cyprus Warbler S. melanothorax on Cyprus? PETER FLINT & ALISON MCARTHUR We firstly describe the history, status, distribution and habitats of the two species on the island. In the light of this the evidence for a decline in Cyprus Warbler numbers in the areas colonised by Sardinian Warbler is assessed and is found to be compelling. Possible reasons for this decline are examined; they are apparently complex, but primarily Cyprus Warbler appears to have stronger interspecific territoriality than Sardinian Warbler and may treat the latter territorially at least to some extent as a conspecific, with some tendency to avoid its home-ranges, especially their centres. Other important factors may be interspecific aggression from Sardinian Warbler (where its population density is high) which might reduce Cyprus Warbler’s ability to establish breeding territories; and competition from Sardinian Warbler for food and for autumn/winter territories. Also, Sardinian Warbler appears to be more efficient in exploiting the habitats of the endemic species, which may have reached a stage in its evolution as an island endemic where it is vulnerable to such an apparently fitter invading congener from the mainland. The changing climate on the island may also be a factor. We conclude that Sardinian Warbler does appear to be displacing Cyprus Warbler, and we recommend that the latter’s conservation status be re-assessed. INTRODUCTION Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala, previously known only as a winter visitor, was found breeding on Cyprus in 1992 (Frost 1995) and is rapidly spreading through the island (eg Cozens & Stagg 1998, Cyprus Ornithological Society (1957)/BirdLife Cyprus annual reports and newsletters, Ieronymidou et al 2012) often breeding at high densities within the same areas as the endemic Cyprus Warbler S. -

Marmora's Warbler: New to Britain and Ireland J

Marmora's Warbler: new to Britain and Ireland J. Lunn n the late evening of 15th May 1982, G. Lee telephoned me to say that, Iduring that day, at Mickleden Clough, Langsett, South Yorkshire, he had watched a small warbler which he could identify only as a Marmora's Warbler Sylvia sarda. At 07.00 GMT on the following morning, I located the continued.... [Brit. Birds 78: 475-481, October 1985] 475 476 Marmora's Warbler: new to Britain and Ireland bird and watched it for about 35 minutes before losing sight of it; shortly afterwards, it was found about 400m down the valley by other observers, including J. E. Dale. Its identity was confirmed as Marmora's Warbler. Throughout the next few months, until 22nd July, the warbler was watched by many hundreds of observers. It was photographed by A. V. Moon (Brit. Birds 75: plates 145 & 146), John T. Belsey, S. G. D. Cook and John Hewitt (plates 218-220). The record was subsequently accepted as the first for Marmora's Warbler in Britain and Ireland. Description First impressions were of a small warbler, strikingly blue-grey in colour, closely resembling a Dartford Warbler S. undata in shape, and with a noticeably long tail. PLUMAGE Striking: at a distance appeared brown-washed grey or buffy-grey; feather uniform blue-grey, recalling adult Cuckoo tips appeared abraded. Cuculus canorus, this emphasised by dark vege• BARE PARTS Legs originally described as tation background. At closer range, head straw-yellow, later as yellow-orange (differ• appeared darker, especially around lores, ence perhaps due to lighting effects?). -

Songbird Remix Africa

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Procedural Maps by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix Cool ‘n’ Unusual Birds 3 Contents Manual Introduction and Overview 3 Model and Add-on Crest Quick Reference 4 Using Songbird ReMix and Creating a Songbird ReMix Bird 5 Field Guide List of Species 9 Parrots and their Allies Hyacinth Macaw 10 Pigeons and Doves Luzon Bleeding-heart 12 Pink-necked Green Pigeon 14 Vireos Red-eyed Vireo 16 Crows, Jays and Magpies Green Jay 18 Inca or South American Green Jay 20 Formosan Blue Magpie 22 Chickadees, Nuthatches and their Allies American Bushtit 24 Old world Warblers, Thrushes and their Allies Wrentit 26 Waxwings Bohemian Waxwing 28 Larks Horned or Shore Lark 30 Crests Taiwan Firecrest 32 Fairywrens and their Allies Purple-crowned Fairywren 34 Wood Warblers American Redstart 37 Sparrows Song Sparrow 39 Twinspots Pink-throated Twinspot 42 Credits 44 2 Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher, DAZ 3D. Songbird ReMix Cool ‘n’ Unusual Birds 3 Manual & Field Guide Copyrighted 2012 by Ken Gilliland - www.songbirdremix.com Introduction The “Cool ‘n’ Unusual Birds” series features two different selections of birds. There are the “unusual” or “wow” birds such as Luzon Bleeding Heart, the sleek Bohemian Waxwing or the patterned Pink-throated Twinspot. All of these birds were selected for their spectacular appearance. The “Cool” birds refer to birds that have been requested by Songbird ReMix users (such as the Hyacinth Macaw, American Redstart and Red-eyed Vireo) or that are personal favorites of the author (American Bushtit, Wrentit and Song Sparrow). -

Dartford Warbler 8 Dragonflies of Somerset 9 Desert Island Birds 11 Walks and Talks 13

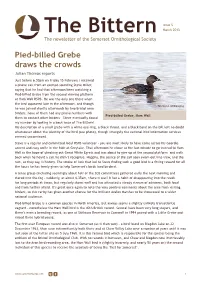

Issue 5 The Bittern March 2013 The newsletter of the Somerset Ornithological Society Pied-billed Grebe draws the crowds Julian Thomas reports Just before 6.30pm on Friday 15 February I received a phone call from an excited-sounding Steve Miller, saying that he had that afternoon been watching a Pied-billed Grebe from the second viewing platform at Ham Wall RSPB. He was the only one there when the bird appeared late in the afternoon, and though Tim Taylor, WildImaging he was joined shortly afterwards by two Bristol area birders, none of them had any phone numbers with Pied-billed Grebe, Ham Wall them to contact other birders – Steve eventually found my number by looking in a back issue of The Bittern! His description of a small grebe with a white eye-ring, a black throat, and a black band on the bill left no doubt whatsoever about the identity of the bird (see photo), though strangely the national bird information services seemed unconvinced. Steve is a regular and committed local RSPB volunteer – you are most likely to have come across his Geordie accent and easy smile in the hide at Greylake. That afternoon he chose at the last minute to go instead to Ham Wall in the hope of checking out Great White Egrets and was about to give up at the second platform and walk back when he heard a call he didn’t recognise. Happily, the source of the call soon swam out into view, and the rest, as they say, is history. The stroke of luck that led to Steve finding such a good bird is a fitting reward for all the hours he has freely given to help Somerset’s birds (and birders). -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 279 US tally: 393 Total world: 1,496 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70. -

British Birds the Dartford Warbler in the United Kingdom in 1994

British Birds Established 1907; incorporating 'The Zoologist', established 1843 The Dartford Warbler in the United Kingdom in 1994 David W. Gibbons and Simon Wotton ABSTRACT A survey of breeding Dartford Warblers Sylvia undata in the UK in 1994 recorded a total of 1,600-1,670 territories, though it is likely that the actual population was slightly high er (1,800-1,890 territories). This represents a near four-fold increase in population since an earlier survey in 1984. Although recorded in nine counties, more than three-quarters of the pop ulation was restricted to two (Dorset and Hampshire), with most of the rest in Devon and Surrey. The most likely cause of the population increase is the recent run of mild winters, though habitat change may have played a part. Despite such a marked increase in numbers, the species' range is still much reduced compared with that of earlier centuries, and 75% of its current population is still restricted to only 24 sites. In the United Kingdom, Dartford Warblers Sylvia undata are confined largely to the remaining fragments of lowland heathland and, as a consequence of the interest in the flora and fauna of this much-threatened habitat, their populations and ecology have been well studied (Tubbs 1963, 1967; Bibby & Tubbs 1975; Bibby 1979a & b; Robins & Bibby 1985a; Westerhoff & Tubbs 1991; Catchpole & Phillips 1992). Historically, the Dartford Warbler had a much wider distribu tion, and was presumably more abundant, than in recent years. In the nineteenth century, its breeding range extended from Suffolk in the east to Cornwall in the [Brit. -

T R E N D S I N N I G H T J a R , W O O D L a R K a N D D a R T F O R D W a R B L E R O N T H E D O R S E T H E a T H S , 1

Trends in Nightjar, Woodlark and Dartford Warbler on the Dorset Heaths, 1991 - 2013 Trends in Nightjar, Woodlark and Dartford Warbler on the Dorset Heaths, 1991 - 2013 Date: 11th August 2014 Version: Final Recommended Citation: Liley D and Fearnley, H. (2014) Trends in Nightjar, Woodlark and Dartford Warbler on the Dorset Heaths, 1991-2013. Footprint Ecology. Cover photograph © James Lowen. http://www.jameslowen.com/photographer-1.html Trends in Nightjar, Woodlark and Dartford Warbler on the Dorset Heaths, 1991 - 2013 Summary An understanding of the direction, magnitude, and the timing of changes in bird populations is fundamental to inform conservation. In this report we plot the trends in the numbers of the three key heathland breeding bird species: nightjar, woodlark and Dartford warbler, on the Dorset Heaths over the period 1991-2013. This period encompassed various pulses of habitat management on the heaths, including the Heritage Lottery funded Tomorrow’s Heathland Heritage work. More recently, and in response to growing urban pressures on many heathland sites, various projects have been initiated to reduce the impacts associated with urban development. National surveys of each species have been conducted at roughly twelve year intervals, and these have provided snapshots of the status of each species in Dorset. Here for the first time we fill in the gaps between the national surveys, modelling trends in the numbers of each species. We have pooled from 46 survey locations, representing over half of the Dorset Heathlands SPA. Across all sites combined, nightjar numbers rose steadily in the early 1990s, peaking in 1996. Numbers remained relatively stable through to 2000, after which a general decline (with some marked fluctuations) is evident, with numbers dropping to a similar level to 1991. -

The Biodiversity of Small Passerine Birds at Wetlands: Species Loss and Effects of Climate Change

Biodiversity International Journal Research Article Open Access The biodiversity of small passerine birds at wetlands: species loss and effects of climate change Abstract Volume 2 Issue 3 - 2018 This research aims to analyse the biodiversity of small birds (passerines) and its trends in a Ignacio Garcia Peiro Western Mediterranean semi-arid wetland by means of captures for ringing during fourteen- years (1991-2014). The palustrine species outnumbered non-palustrine in individuals but Department of Ecology & Hydrology, University of Murcia, Spain not in species. The diversity of passerines is about two-fifth parts of the total diversity of Correspondence: Ignacio García Peiró, Department of birds of the wetland. Fourteen-palustrine species outweigh as dominants in number and Ecology & Hydrology, Faculty of Biology, University of Murcia, C/ biomass, belonging to the family Acrocephalidae or Reed warblers. The heavyweight of El Salvador, 17-4D, 03203 Elche (Alicante), Spain, Tel (00)349- non-palustrine species is exerted by a Leaf warbler, the Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus 654-51777, Fax (00)965-4213-20, Email [email protected] collybita. The biodiversity falls significantly over time with losses of 0.072 nats per year. Similar trends identified for the richness, which leaves losses of 1 species per year, ranging Received: May 14, 2018 | Published: June 12, 2018 from 9 to 10 species gains and losses for the overall passerine’s assemblage. Diversity and richness correlate weakly and negatively with rainfall and positively with temperature, accounting from 15.1 to 20.4% of the variation in diversity of passerines, respectively. The loss of diversification of invertebrate preys due to global warming is considered a probable effect of the species decline. -

Red Data Book of European Vertebrates : a Contribution to Action Theme N° 11 of the Pan-European Biological and Landscape Diversity Strategy, Final Draft

Strasbourg, 5 July 2001 T-PVS (2001) 31 [Bern\T-PVS 2001\tpvs31e_2001] English only CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee Preliminary European Red List of Vertebrates Draft for comments - Volume 1 - Joint project between the Council of Europe and the European Environment Agency, based on WCMC draft from 1998. Co-ordinated by the European Topic Centre/Nature Conservation – Paris This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS (2001) 31 - II - Comments should be sent to: European Topic Centre for Nature Protection and Biodiversity MNHN 57 rue Cuvier 75231 PARIS Cedex, France [email protected] - III - T-PVS (2001) 31 About this draft Red List This document is the result of a joint project between the European Environment Agency and the Council of Europe to develop a preliminary European Red List of Vertebrates. It is based on a first draft by WCMC in 1998. Except for Birds (Birdlife International, 1994), no assessment is yet available on the conservation status of Vertebrate species at European level, while Red Books exist at national level in almost all European countries. On the other hand, a global list of threatened species is published and maintained up-dated by IUCN according to well defined criteria (IUCN, 2000). The present assessment is a first attempt to identify the most threatened Vertebrates species at European level, building upon a first analysis of the list of globally threatened species present in Europe (WCMC, 1998) and taking into account the most recent available overviews on European species distribution provided by the various European atlas committees (European Bird Census Council; Societas Europaea Herpetologica, Societas Europea Mammalogica).