Clare, Suffolk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Excursions 1996. Report and Notes on Some Findings. 13 April 1996

EXCURSIONS 1996 Reportandnotesonsomefindings 13 April.John Blatchly,TimothyEaston,EdwardMartinandPeterNortheast RaylonandLittle Wenham Raylon,St Mag's Church. The annual general meeting was held here by kind permission of the Revd T. Wells. The church is wholly of late-13th/early 14th-century construction, except for the ruined tower. The chancel is basically 13th-century (windowtracery, priest's doorway and fine piscina) but with 14th-century additions (crocketed pinnacles at the east end and 'founder's tomb' in the north wall). The nave is early 14th-century (window tracery). The 15th-century tower (willsof the 1440s and 1450srefer to its building) containing four bells fell in the mid-17th century (facultypetition of 1750);the remaining bell is now housed in a small west protruberance. Items of note are: part of a small female figure, the remains of a brass to Elizabeth Reydon, and the inscription for Thomas her brother, both of whom died in 1479; the founder's tomb, which formerly held a stone effigyof Sir Robert de Reydon (d. 1323)bearing the Reydon arms —seen by Tillotson at the end of the 16th century; wooden brackets, formerly supporting the roodbeam, over the chancel arch; a monument on the north wall to the Revd John Mayer (d. 1664; see D.N.B.) who served here for thirty-three years, detailing his publications; and a carving of a dragon with a curved tail on the exterior of the east wall, below the north pinnacle. LittleWenham,All Saints'Church(by kind permission of the Redundant Churches Fund). The church, of late 13th-century date, is isolated, in a group with the Hall, with which it is probably contempor- ary and shared some of the same masons, as they have decorative details in common. -

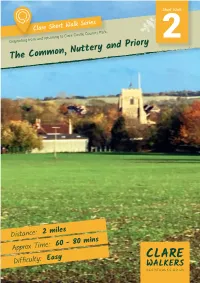

The Common, Nuttery and Priory

Short Walk Clare Short Walk Series Originating from and returning to Clare Castle Country Park. The Common, Nuttery and Priory 2 Distance: 2 miles Approx Time: 60 - 80 mins More walks are available by visiting clarewalks.co.uk or clarecastlecountrypark.co.uk Difficulty: Easy Clare Short Walk 2 Short Walk Series The Clare Short Walks Series is a collection of four overlapping walks aimed at walkers who wish to explore Clare and its surrounds. The walks are all under 2.5 miles and are designed to take between 60 and 80 minutes at a leisurely pace. All the walks originate and end in Clare Castle Country Park. From the car park walk with the ‘Old Goods 4 Follow the path down past the cemetery, Shed’ on your right towards the Station turn right at the bottom and walk around House. Before reaching the house turn left past the field, keeping the field on your right. the moat and, keeping the field on your right, walk along Station Road to the town centre. 5 When you reach a large metal gate, go At the top of Station Road turn right. Cross the through this gate and walk down past Clifton road towards the Co-op and walk along Church Cottages to Stoke Road. Walk across this road Lane, past the Church. and then along Ashen Road. Keep on the right here to face oncoming traffic. Walk across the 2 Cross the High Street, turning right and bridge and then for about 50 metres to the then left through the cemetery gates. -

Elizabeth De Burgh Lady of Clare

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ELIZABETH DE BURGH, LADY OF CLARE (1295-1360): THE LOGISTICS OF HER PILGRIMAGES TO CANTERBURY JENNIFER WARD Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages was regarded as an integral part of religious practice. The best known pilgrims to Canterbury are those of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, enjoying each other's company and telling their stories as they journeyed to the shrine of St Thomas Becket. Chaucer chose his pilgrims from a broad spectrum of society. Many people, rich and poor, visited local as well as the major shrines in England, and travelled abroad, as did the Wife of Bath and Margery Kempe, to visit the shrines at Cologne, Santiago de Compostella, Rome and Jerusalem. Their journeys are recorded in their own and others' accounts. What is less well known are the accounts of pilgrimages in royal and noble household documents which record the preparations, the journey itself, provisioning and transport. Some also record the religious dimension of the pilgrimage, the visits and offerings to shrines, and details of prayers and masses. Elizabeth de Burgh, Lady of Clare, was a member of the higher nobility; she was the youngest daughter of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester and Hertford (d.1295), sister of the last Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, yvho was killed at Bannockburn in 1314, and cousin of Edward III.1 Three years after her brother's death, she and her two elder sisters inherited equal shares of the Clare lands in England, Wales and Ireland which were valued at c.£6,000 a year.2 Elizabeth's share lay mainly in East Anglia, with Clare castle (Suffolk) as Uie administrative centre and principal residence; she came to style herself Lady of Clare, and she was refened to in her records as the Lady. -

Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

Clare Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan September 2008 Clare Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan Planning & Engineering Services St Edmundsbury Borough Council Western Way Bury St Edmunds IP33 3YS Contents Introduction Summary of special interest of the conservation area Assessing special interest: 1 Location and setting: • context • map of the conservation area • general character and plan form 2 Historic development and archaeolog: • origins and historic development of the conservation area • archaeology and scheduled ancient monuments 3 Spatial analysis: • character and interrelationship of spaces • key views and vistas 4 Character analysis: • definition and description of character areas: Market Hill High Street Nethergate Street Clare Castle Country Park and Clare Priory Bridewell Street/Callis Street/Church Street Cavendish Road • surfaces and street furniture • neutral and negative areas • general condition of the area and buildings at risk • problems, pressures and capacity for change 5 Key characteristics to inform new development 6 Management proposals for the Clare Conservation Area for 2008-2012 7 Useful information and contacts Bibliography 1 2 Introduction The conservation area appraisal and management plan has been approved as planning guidance by the Borough Council on 23 September 2008. It has been the subject of consultation. Comments received as a result of the consultation have been considered and, where appropriate, the document has been amended to address these comments. This document will, along with the Replacement St Edmundsbury Borough Local Plan 2016, provide a basis by which any planning application for development in or adjacent to the conservation area will be determined. A conservation area is ‘an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. -

Clare Priory

1 CLARE PRIORY Clare priory has the most extensive remains of any Augustinian friary surviving in England, and the plan is practically complete. It is the oldest single house of the Order still inhabited by the friars. The main entrance is along the Ashen road, but there is easy access from Clare Castle Country Park car park. Cross the millstream, walk a few paces along the old railway track and drop down to the left. The main buildings still in existence are the magnificent 14th century Prior's House, and the Infirmary, now converted to a church. Other remains or identified sites include the frater (dining area, with kitchen below), the chapter house with the dormitory above, the cloister, and the monastic church with St Vincent’s chapel. THE AUGUSTINIAN FRIARS. The Augustinian friars (often called 'Austins' in England) have a traditional link with St Augustine of Hippo in North Africa, who lived 354-430 AD. Augustine had a Christian mother, a pagan father – and a brilliant mind. His student days showed excesses. He prayed 'Make me chaste, but not yet'. He searched far meaning in life through philosophers. He admired Bishop Ambrose's oratory, but not his Christian message. Then came a conversion experience in 386 AD. He had been reading St Paul's epistles. In a garden one day he seemed to hear a child's voice saying 'Tolle lege’ (Take up and read). He chanced on Romans 13: 12- 14 'Give up unrighteous acts ……..' and became a Christian. From this expenience derives the Augustinian logo showing a Bible which is afire, a heart pierced by an arrow which transfixes it to that Bible, and the phrase 'Tolle liege'. -

Clare Castle Monitoring of Masonry Repairs CLA 008

Clare Castle Monitoring of masonry repairs CLA 008 Archaeological Monitoring Report SCCAS Report No. 2012/186 Client: Suffolk County Council Author: David Gill November/2012 © Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service Clare Castle Monitoring of masonry repairs CLA 008 Archaeological Monitoring Report SCCAS Report No. 2012/186 Author: David Gill Contributions By: Illustrator:Crane Begg Editor: Richenda Goffin Report Date: November/2012 HER Information Site Code: CLA 008 Site Name: Clare Castle Report Number 2012/186 Planning Application No: N/A Date of Fieldwork: August-October 2012 Grid Reference: TL 7700 4510 Oasis Reference: c1-138611 Curatorial Officer: Dr Jess Tipper Project Officer: David Gill Client/Funding Body: Suffolk County Council Client Reference: ***************** Digital report submitted to Archaeological Data Service: http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/library/greylit Disclaimer Any opinions expressed in this report about the need for further archaeological work are those of the Field Projects Team alone. Ultimately the need for further work will be determined by the Local Planning Authority and its Archaeological Advisors when a planning application is registered. Suffolk County Council’s archaeological contracting services cannot accept responsibility for inconvenience caused to the clients should the Planning Authority take a different view to that expressed in the report. Prepared By: David Gill Date: November 2012 Approved By: Joanna Caruth Position: Senior Project Officer Date: Signed: Contents Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. Site location, geology and topography 3 3. Archaeology and historical background 3 4. Methodology 9 5. Results 9 The castle keep 9 Keep elevations 11 The bailey wall 14 6. Discussion 16 7. Archive deposition 17 8. -

ISABEL DE BEAUMONT, DUCHESS of LANCASTER (C.1318-C.1359) by Brad Verity1

THE FIRST ENGLISH DUCHESS -307- THE FIRST ENGLISH DUCHESS: ISABEL DE BEAUMONT, DUCHESS OF LANCASTER (C.1318-C.1359) by Brad Verity1 ABSTRACT This article covers the life of Isabel de Beaumont, wife of Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster. Her parentage and chronology, and her limited impact on the 14th century English court, are explored, with emphasis on correcting the established account of her death. It will be shown that she did not survive, but rather predeceased, her husband. Foundations (2004) 1 (5): 307-323 © Copyright FMG Henry of Grosmont (c.1310-1361), Duke of Lancaster, remains one of the most renowned figures of 14th century England, dominating the military campaigns and diplomatic missions of the first thirty years of the reign of Edward III. By contrast, his wife, Isabel ― the first woman in England to hold the title of duchess ― hides in the background of the era, vague to the point of obscurity. As Duke Henry’s modern biographer, Kenneth Fowler (1969, p.215), notes, “in their thirty years of married life she hardly appears on record at all.” This is not so surprising when the position of English noblewomen as wives in the 14th century is considered – they were in all legal respects subordinate to their husbands, expected to manage the household, oversee the children, and be religious benefactresses. Duchess Isabel was, in that mould, very much a woman of her time, mentioned in appropriate official records (papal dispensation requests, grants that affected lands held in jointure, etc.) only when necessary. What is noteworthy, considering the vast estates of the Duchy of Lancaster and her prominent social position as wife of the third man in England (after the King and the Black Prince), is her lack of mention in contemporary chronicles. -

Clare Castle Excavations in 2013

Clare Castle Excavations in 2013 Clare Castle is a medieval motte-and-bailey castle of Norman origin built shortly after the 1066 Conquest by the powerful de Clare family. It was a particularly large and imposing castle by medieval standards, but little of the original structure is visible, much now lost, hidden by trees or damaged by later building, including the 19 th century railway line. In 2013, archaeological excavations by local residents supervised by Access Cambridge Archaeology are exploring four sites within the castle grounds. Little is known of the early history of the site of Clare Castle, but documentary evidence suggests that a small priory was there by 1045 AD, possibly associated with a high-status Anglo-Saxon residence and several human skeletons unearthed in 1951: tooth samples recently subjected to isotopic analysis show the owner to have come from the local area. In 1124 the priory was moved to Stoke-by-Clare. Castles (private defended residences of medieval feudal lords) were introduced to England after the Norman Conquest. Soon after 1066, William the Conqueror granted the Clare estate to one of the knights who’d helped him conquer England, Richard fitz Gilbert. Documents show the castle was built by 1090. Its valley-bottom location is easily defended by the river and strategically positioned to dominate both the adjacent town and movement up and down the valley. If there was an Anglo-Saxon lordly residence on the site, building the castle there would emphasise that power had now passed into new hands. Clare Castle was a motte and bailey castle, the most common form of castle in the 11 th and 12 th centuries which went out of fashion as castles with keeps and curtain walls became popular. -

Family Group Record

Family Group Record Page 1 of 3 Husband Charles Reid Bird Born Place 18 Feb 1915 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA LDS ordinance dates Temple Christened Place Baptized 18 Feb 1923 Died Place Endowed 8 Mar 1991 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 24 Jun 1936 SL Buried Place Sealed to parents 12 Mar 1991 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA BIC Married Place Sealed to spouse 1 Jul 1936 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 1 Jul 1936 SL Other Spouse Frances Burnham Married Place Sealed to spouse 5 Jul 1984 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 5 Jul 1984 SL Husband's father Charles William Bird Husband's mother Alice Reid Wife Marian Bricker Born Place 17 Oct 1916 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA LDS ordinance dates Temple Christened Place Baptized 25 Apr 1925 Died Place Endowed 2 May 1983 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 24 Jun 1936 SL Buried Place Sealed to parents 5 May 1983 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA BIC Wife's father Ernest Wilford Bricker Wife's mother Mabel Jean Timpson Children List each child in order of birth. LDS ordinance dates Temple 1 F Sherron Evelyn Bird Born Place Baptized 5 Oct 1938 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 27 Feb 1947 Christened Place Endowed 8 Jan 1962 SL Died Place Sealed to parents BIC Buried Place Spouse Kent B Linebaugh Married Place Sealed to spouse 12 Jan 1962 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 12 Jan 1962 SL 2 F Linda Marian Bird Born Place Baptized 17 May 1941 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 2 Feb 1950 Christened Place Endowed 15 Sep 1962 SL Died Place Sealed to parents Buried Place Spouse Philip Dayton Thorpe Married Place Sealed to spouse 24 Sep 1962 Logan, Cache, Ut 24 Sep 1962 LG 3 F Mary Annette Bird Born Place Baptized 20 Mar 1943 Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA 26 Jul 1951 Christened Place Endowed Died Place Sealed to parents BIC Buried Place Spouse Gary LeRoy Anderson Married Place Sealed to spouse 11 Aug 1961 (Div) Salt Lake City, SL, Utah, USA Prepared by Address Devin D. -

The Land of Morgan

Archaeological Journal ISSN: 0066-5983 (Print) 2373-2288 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 The Land Of Morgan G. T. Clark To cite this article: G. T. Clark (1880) The Land Of Morgan, Archaeological Journal, 37:1, 117-128, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1880.10851929 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1880.10851929 Published online: 14 Jul 2014. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raij20 Download by: [137.189.171.235] Date: 13 June 2016, At: 18:18 Cije archaeological journal. JUNE, 1880. THE LAND OF MORGAN. CONCLUDING ΡΛΕΤ, By G. T. CLARK. Earl Gilbert was but twenty-three years old at his death in June 1314, and had survived his father nineteen years. By his wife Maud, who appears to have been a daughter of John, son of Richard cle Burgh, Earl of Ulster, he had one son, John, who died just before his father, and was buried at Tewkesbury in the Lady chapel. With the earl therefore ended the main line of the great house of Clare, Earls of Gloucester and Hertford. The countess declared herself not only pregnant but quick with child, a statement which gave rise to some very curious legal proceedings between her and the husbands of the sisters and presumptive co-heirs, nor was it until 1317 that the dispute was settled and all hope of issue given up. The case was raised by Hugh le Despenser, Downloaded by [] at 18:18 13 June 2016 husband of the elder co-heir, who prayed for a division of the estates and tendered homage. -

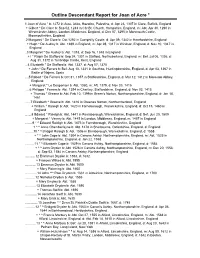

Outline Descendant Report for Joan of Acre

Outline Descendant Report for Joan of Acre * 1 Joan of Acre * b: 1272 in Acre, Akko, Hazafon, Palestine, d: Apr 23, 1307 in Clare, Suffolk, England + Gilbert * De Clare b: Sep 02, 1243 in ChriSt. Church, Hampshire, England, m: Abt. Apr 30, 1290 in Westminster Abbey, London, Middlesex, England, d: Dec 07, 1295 in Monmouth Castle, Monmouthshire, England .2 Margaret * De Clare b: Oct 1292 in Caerphilly Castle, d: Apr 09, 1342 in Herefordshire, England + Hugh * De Audley b: Abt. 1289 in England, m: Apr 28, 1317 in Windsor, England, d: Nov 10, 1347 in England ..3 Margaret * De Audley b: Abt. 1318, d: Sep 16, 1348 in England + I * Ralph De Stafford b: Sep 24, 1301 in Stafford, Northuberland, England, m: Bef. Jul 06, 1336, d: Aug 31, 1372 in Tunbridge Castle, Kent, England ...4 Elizabeth * De Stafford b: Abt. 1337, d: Aug 07, 1375 + John * De Ferrers b: Bef. Aug 10, 1331 in Southoe, Huntingdonshire, England, d: Apr 03, 1367 in Battle of Najera, Spain ....5 Robert * De Ferrers b: Oct 31, 1357 in Staffordshire, England, d: Mar 12, 1412 in Merevale Abbey, England + Margaret * Le Despenser b: Abt. 1360, m: Aft. 1379, d: Nov 03, 1415 .....6 Philippa * Ferrers b: Abt. 1394 in Chartley, Staffordshire, England, d: Nov 03, 1415 + Thomas * Greene b: Abt. Feb 10, 1399 in Green's Norton, Northamptonshire, England, d: Jan 18, 1461 ......7 Elizabeth * Greene b: Abt. 1416 in Greenes Norton, Northumberland, England + William * Raleigh b: Abt. 1420 in Farneborough, Warwickshire, England, d: Oct 15, 1460 in England .......8 Edward * Raleigh b: Abt.