Excursions 1996. Report and Notes on Some Findings. 13 April 1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Companyoverview

company overview Major Food Group (MFG) is a New York based restaurant and hospitality company founded by Mario Carbone, Rich Torrisi and Jeff Zalaznick. The founders all exhibit a wealth of knowledge in the food, hospitality and business sectors. MFG currently operates twelve restaurants: Carbone (New York, Hong Kong, Las Vegas), ZZ’s Clam Bar, Dirty French, Santina, Parm (Soho, Yankee Stadium, Upper West Side, Battery Park) and Sadelle’s. MFG also operates a Lobby Bar at the Ludlow Hotel and provides all F&B and event services for the Ludlow Hotel. MFG has many exciting new projects in the works, as well, including the iconic restoration of the Four Seasons Restaurant. MFG is committed to creating hospitality experiences that are inspired by New York and its rich culinary history. They aim to bring each location they operate to life in a way that is respectful of the past, exciting for the present and sustainable for the future. They do this through the concepts that they create, the food and beverage they serve and the experience they provide for their customers. MAJOR FOOD GROUP 2 existing restaurant concepts Carbone Santina New York Las Vegas Hong Kong Sadelle’s ZZ’s Clam Bar Parm Soho Upper West Dirty French Battery Park Yankee Stadium Lobby Bar The Ludlow Hotel MAJOR FOOD GROUP 3 Carbone opened in 2013 and is located in the heart of Greenwich Village. Carbone occupies the space that once housed the legendary Rocco Restaurant, which was one of the most historic Italian-American eateries in Manhattan. Built on the great bones that were already there, Carbone pays homage to the Italian-American restaurants of the mid-20th century in New York, where delicious, exceptionally well-prepared food was served in settings that were simultaneously elegant, comfortable and unpretentious. -

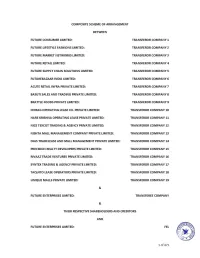

Composite Scheme Arrangement

COMPOSITE SCHEME OF ARRANGEMENT BETWEEN FUTURE CONSUMER LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 1 FUTURE LIFESTYLE FASHIONS LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 2 FUTURE MARKET NETWORKS LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 3 FUTURE RETAIL LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 4 FUTURE SUPPLY CHAIN SOLUTIONS LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 5 FUTUREBAZAAR INDIA LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 6 ACUTE RETAIL INFRA PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 7 BASUTI SALES AND TRADING PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 8 BRATTLE FOODS PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 9 CHIRAG OPERATING LEASE CO. PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 10 HARE KRISHNA OPERATING LEASE PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 11 NICE TEXCOT TRADING & AGENCY PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 12 NISHTA MALL MANAGEMENT COMPANY PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 13 OJAS TRADELEASE AND MALL MANAGEMENT PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 14 PRECISION REALTY DEVELOPERS PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 15 RIVAAZ TRADE VENTURES PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 16 SYNTEX TRADING & AGENCY PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 17 TAQUITO LEASE OPERATORS PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 18 UNIQUE MALLS PRIVATE LIMITED: TRANSFEROR COMPANY 19 & FUTURE ENTERPRISES LIMITED: TRANSFEREE COMPANY & THEIR RESPECTIVE SHAREHOLDERS AND CREDITORS AND FUTURE ENTERPRISES LIMITED: FEL 1 of 471 & RELIANCE RETAIL VENTURES LIMITED: RRVL & THEIR RESPECTIVE SHAREHOLDERS AND CREDITORS AND FUTURE ENTERPRISES LIMITED: FEL & RELIANCE RETAIL AND FASHION LIFESTYLE LIMITED: RRVL WOS & THEIR RESPECTIVE SHAREHOLDERS AND CREDITORS UNDER SECTIONS 230 TO 232 AND OTHER APPLICABLE PROVISIONS OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2013 2 of 471 PARTS OF THE SCHEME The Scheme (as defined hereinafter) is divided into the following parts: 1. PART I deals with the overview, description of Parties (as defined hereinafter) and rationale for this Scheme; 2. PART II deals with the definitions, share capital and date of taking effect and implementation of this Scheme; 3. -

Today Your Barista Is: Genre Characteristics in the Coffee Shop Alternate Universe

Today Your Barista Is: Genre Characteristics in The Coffee Shop Alternate Universe Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Katharine Elizabeth McCain Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Sean O’Sullivan, Advisor Matthew H. Birkhold Jared Gardner Elizabeth Hewitt 1 Copyright by Katharine Elizabeth McCain 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation, Today Your Barista Is: Genre Characteristics in The Coffee Shop Alternate Universe, works to categorize and introduce a heretofore unrecognized genre within the medium of fanfiction: The Coffee Shop Alternate Universe (AU). Building on previous sociological and ethnographic work within Fan Studies, scholarship that identifies fans as transformative creators who use fanfiction as a means of promoting progressive viewpoints, this dissertation argues that the Coffee Shop AU continues these efforts within a defined set of characteristics, merging the goals of fanfiction as a medium with the specific goals of a genre. These characteristics include the Coffee Shop AU’s structure, setting, archetypes, allegories, and the remediation of related mainstream genres, particularly the romantic comedy. The purpose of defining the Coffee Shop AU as its own genre is to help situate fanfiction within mainstream literature conventions—in as much as that’s possible—and laying the foundation for future close reading. This work also helps to demonstrate which characteristics are a part of a communally developed genre as opposed to individual works, which may assist in legal proceedings moving forward. However, more crucially this dissertation serves to encourage the continued, formal study of fanfiction as a literary and cultural phenomenon, one that is beginning to closely analyze the stories fans produce alongside the fans themselves. -

Food Beer Wine Amaro Fernet G&T Spirits

FOOD BEER WINE AMARO FERNET G&T SPIRITS — Bar Snacks — Spice Roasted Nuts £3.50 (vg) Scotch Egg £4.50 marmite mayo Marinated Olives £3.50 (vg) Tempura Cauliflower £5 (vg) Padron Peppers £5 (vg) pickles, vegan ranch & hot sauce smoked sea salt Halloumi Fries £6 (v) Buttermilk Fried Chicken £6.50 mint yogurt, Aleppo pepper Korean hot sauce, sesame & coriander — Mains — — Grill — — Salads — Fish & Chips Chargrilled Beef Burger & Fries Kale & Avocado Salad Camden Hells battered cod Swiss cheese, lettuce, onion & vegan yoghurt dressing, toasted mushy peas & tartare sauce gherkin sunflower seeds £12.50 £11.50 £10 Black Bean & Chipotle Burger (vg) Grilled Ham Grilled Chicken Satay Salad pickles, harissa mayo & fries with two fried eggs & chips Asian slaw, peanut sauce, chilli £11.50 £10 sesame & lime £12.50 Seabream fillet Full English Breakfast mash, grilled leeks & salsa verde bacon, sausage, black pudding, Add grilled halloumi £2.50 £13.50 fried eggs, mushroom, beans, Add grilled chicken £2.50 tomato & toast Steak & Blue Cheese Pie £10 charred hispi, mash, red wine sauce £13 — Sides — — Dessert — Rigatoni & Kale Pesto toasted pumkin seeds, vegan Chips / Fries £4 Chocolate Fondant £6.50 Green Salad £3.5 Vegan Chocolate Brownie parmesan £6.50 £10.50 For allergen advice please ask your server — www.SingerTavern.com — @singertavern [email protected] Draught Belgian / Wheat Camden Hells Lager UK 4.6% £5.20 Blanche De Bruxelles BE 4.5% £5.00 Hawkes Urban Orchard Cider UK 4.5% £5.20 La Chouffe BE 8.0% £6.00 Camden IPA UK 5.8% £5.20 La Trappe -

Final Gazette Notices -Continued Shenron Group Security Limited 11184361 Shellys Sparkle and Shine Ltd 10675663

FINAL GAZETTE NOTICES -CONTINUED SHENRON GROUP SECURITY LIMITED 11184361 SHELLYS SPARKLE AND SHINE LTD 10675663 09/07/2019 SHEPHERD BERKELEY LTD 10592233 SHENLEY DRIVEWAYS LTD 10781357 09/07/2019 SHEPOLLIC LTD 11183852 SKYCAFE LTD 11188207 09/07/2019 SHEPOLON LTD 11184017 SKYFI GLOBAL NETWORK LIMITED 11178784 09/07/2019 SHEPTATIC LTD 11183701 SKYSBIKE LIMITED 11182959 09/07/2019 SHERAPUS LTD 11183621 SKYWAY CLEANING SERVICES LTD 10780026 09/07/2019 SHERWOOD COMMERCIAL SERVICES LIMITED 11187351 SLATE PROJECTS LTD. 08479975 09/07/2019 SHIELDS CLEAN LIMITED 08407382 SLB JOINERY LTD 09414537 09/07/2019 SHIREBURN SELECTION LTD 11182475 SLICK CONTRACTORS LTD 11182974 09/07/2019 SHOPERHOLIC LIMITED 11151534 SLIM JAB-SKINNY JAB LTD 11187950 09/07/2019 SHOPICK LTD 11183933 SMARTBITES LTD 10788253 09/07/2019 SHOP MY LOCAL LIMITED 11177493 SMART BLOCKCHAIN SOLUTIONS LIMITED 11186856 09/07/2019 SHOPWIRED CANADA LTD 08519700 SMART ENERGY LOGISTICS LTD 09412479 09/07/2019 SHOULDER(SHELF) LTD 11187299 SMARTER HEATING SERVICES LIMITED 09515054 09/07/2019 SHOWMAN MEDIA LIMITED 06583349 SMART SAVE AUTOMOTIVE LTD 11187491 09/07/2019 SHOWTIME GUARDING LTD 08977681 S M BRADY ROOFING LTD 09476771 09/07/2019 SHRANK L DJ HOLDINGS LTD 11186959 SMC EVENTS LTD 09978109 09/07/2019 SHRI ANNAPURNA LIMITED 11184044 SMERSH LIMITED 08875670 09/07/2019 SHURIE DEFENCE LTD 11188427 SMITHY'S GOURMET SERVICES LTD 10787942 09/07/2019 SHUT UP STUDIO LIMITED 09417154 SMMF LIMITED 11185110 09/07/2019 SHWAS CONTRACT LIMITED 11176371 SMOKING ROCKET ONLINE LIMITED 11188096 09/07/2019 SIGMA TELECOMS LIMITED 11178497 SM OPERATIONS LIMITED 10780981 09/07/2019 SIGNATURE SPECIALISTS CARS LIMITED 11184604 SNACK TO THE FUTURE LIMITED 11186695 09/07/2019 SIGN RECRUIT LTD 10785030 SNOWFLAKES AND STRAWBERRIES LIMITED 08874051 09/07/2019 SIGNUM INTERIORS LIMITED 09421160 SN SERVICE WORLDWIDE LTD 11183152 09/07/2019 SILK FINANCE GROUP LIMITED 11183679 SNUZYBABY LIMITED 11182120 09/07/2019 SILKGATE SERVICES INC. -

Outliers – Stories from the Edge of History Scullion Daydreams

Outliers – Stories from the edge of history is produced for audio and specifically designed to be heard. Transcripts are created using human transcription as well as speech recognition software, which means there may be some errors. Outliers – Stories from the edge of history Season Two, Episode Nine Scullion Daydreams By Steven Camden (Polarbear) We exist in the kitchens, thumping guts of the court, Our stories are quiet and too common to tell, What those above us do, it does not concern us, We know our roles, and we do them well. July. Robert: They are here. Hundreds of them. Thousands perhaps. A legion of servants following their precious prince. They say he does not speak a word of English. That he and the queen have never but met. Now he is to be King of England, with the blessing of Rome. The old religion returns, gilded in gold. The ground rumbled as their procession rolled into court yesterday. I could not get out to see. I would be scolded for trying, but pans danced on their hooks from the trampling of feet. He brought them with him as though we were not already here, already good enough, as though we did not even exist. Now all these new mouths will need feeding, like this staff was not already stretched to its limits. Spaniards. "What those above us do, does not concern us, Robert. Know your role and do it well". I hear Father's voice more these past months. His phrases repeat in my mind as I sweep, scrape and stack like a good scullion should. -

Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

Clare Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan September 2008 Clare Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan Planning & Engineering Services St Edmundsbury Borough Council Western Way Bury St Edmunds IP33 3YS Contents Introduction Summary of special interest of the conservation area Assessing special interest: 1 Location and setting: • context • map of the conservation area • general character and plan form 2 Historic development and archaeolog: • origins and historic development of the conservation area • archaeology and scheduled ancient monuments 3 Spatial analysis: • character and interrelationship of spaces • key views and vistas 4 Character analysis: • definition and description of character areas: Market Hill High Street Nethergate Street Clare Castle Country Park and Clare Priory Bridewell Street/Callis Street/Church Street Cavendish Road • surfaces and street furniture • neutral and negative areas • general condition of the area and buildings at risk • problems, pressures and capacity for change 5 Key characteristics to inform new development 6 Management proposals for the Clare Conservation Area for 2008-2012 7 Useful information and contacts Bibliography 1 2 Introduction The conservation area appraisal and management plan has been approved as planning guidance by the Borough Council on 23 September 2008. It has been the subject of consultation. Comments received as a result of the consultation have been considered and, where appropriate, the document has been amended to address these comments. This document will, along with the Replacement St Edmundsbury Borough Local Plan 2016, provide a basis by which any planning application for development in or adjacent to the conservation area will be determined. A conservation area is ‘an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. -

Cong Sounds Peace Overture

■ < V'; The Weather Kaak First-Day Open Leader Fair tonight. Low 50 to 55, chance - of rain 10 per cent. Goudy Page 16 lEuf mnn I Tuesday with a 30 per cent V chance of showers; hl^ in the .low 80s. MANCHESTER — 4 City o f Village Charm TWENTY-TWO PAGES MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11,19^2 VOL. XCI. No. 291 PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS Students Take Cong Sounds ^Strike’ Recess tj Over Nation Peace Overture previous formula for the makeup By THE ASSOaATED PRESS SAIGON (AP) - The Viet Once again it called on the of the government of national Cong issued a new peace United States to withdraw all its Negotiations remained deadlocked today in the concord—a three-segment coali statement today saying it is troops from Vietnam, to stop Philadelphia teachers strike, but Kansas City youngsters supporting the regime of Presi tion composed of (1) members of "prepared to accept a were back in class and there were signs of progress in several dent Nguyen Van Thieu, and to the Provisional Revolutionary other school walkouts across the country. - ^ provisional government of halt the bombing and mining of Government, (2) members of the national concord that shall be Saigon administration excluding Spokesmen for both the P'riday because custodians and North Vietnam. dominated by neither side." Thieu, and (3) representatives of teachers' union and the maintenance workers were on U.S, sources In Saigon inter " Should the U.S. government other political forces in South Philadelphia School Board ex strike and trash had accumulated preted this as a concession that really respect the South Viet Vietnam ""including those who, pressed doubt Sunday that the at the schools. -

Teacher's Toolkit

The Clerk’s Fantastic Feast Time Explorers has been created for schools by Historic Royal Palaces to inspire learning about history, both at our palaces and in the classroom. Combining immersive storytelling with digital technology and hands-on workshops, we offer learning experiences that enthuse children, nurture imagination and develop skills of historical enquiry, problem-solving and teamwork. Digital missions are interactive story adventures designed to encourage your pupils to explore the rich and dramatic histories of our palaces. This Teacher’s Toolkit has been produced to support you and your pupils to successfully complete ‘The Clerk’s Fantastic Feast’ mission. It is designed to be a flexible resource for teachers of pupils aged 7-11 years old and has been mapped to the aims of the new National Curriculum. This toolkit provides you with ideas and resources to extend your pupils’ learning before and after their visit. We hope it acts as a useful stimulus and support to help ignite your pupils’ passion for learning about history. Your mission... It is 1543 and Katherine Parr has just become Henry VIII’s sixth wife. It’s a dangerous job being married to Henry, so Queen Katherine is counting on you to help the Kitchen Clerk prepare an amazing banquet. If you fail, she could be in major trouble…so good luck! Time Explorers – Teacher’s Toolkit Classroom Challenges The Clerk’s Fantastic Feast Classroom challenges This section of the toolkit provides a series of classroom challenges that have been designed to offer a cross-curricular approach. The preparatory challenges can be used to develop your pupils’ historical research skills and to build their knowledge prior to the main mission activity. -

Gannon, YMCA Considering Joint Athletic Facility Student Living Revamped

( a «tud»nt-»dlt»d eomwunltjj wookly Vol. 37 No. 1 Gannon University, Erio, Pa. Wednesday, Soptombor 9. 1981 Gannon, YMCA considering joint athletic facility by Dov« Schulti may not be possible," he the university would pay the student union and athletic This planning will not be Austin, head of women's Since Gannon is said. Y for the privilege. (See facility. delayed or advanced by the athletics; Athletic Director considering acquiring an The downtown YMCA and story page 8.) Gannon has been working discussions with the Y on a Bud El well; Dr. David Frew, athletic facility and the Gannon have a number of on plans for such a complex joint center, Scottino said. director of MBA program; downtown YMCA is things in common that could Discussion of possible joint since last spring when Weber The committee is, however, Rev. Addison Yehl, considering relocating their make a joint facility operation and use of a fitness Murphey Architects drew up discussing the Y proposal, chemistry professor, SGA fitness center, the Y has practical, according to center was prompted by initial designs for the too. President John Bloomstine; proposed that both sides Scottino. Both institutions officials of the downtown Y, structure. The committee includes Mary Kloecker, sophomore could possibly work together are located downtown. Both who are apparently not Now Gannon's planning Rev. Francis Haas, social work major; and Pete on a joint facility. want to build the same type happy with their present committee is working on instructor of psychology; Russo. Russo is a Gannon A Gannon planning facilities. -

Clare Priory

1 CLARE PRIORY Clare priory has the most extensive remains of any Augustinian friary surviving in England, and the plan is practically complete. It is the oldest single house of the Order still inhabited by the friars. The main entrance is along the Ashen road, but there is easy access from Clare Castle Country Park car park. Cross the millstream, walk a few paces along the old railway track and drop down to the left. The main buildings still in existence are the magnificent 14th century Prior's House, and the Infirmary, now converted to a church. Other remains or identified sites include the frater (dining area, with kitchen below), the chapter house with the dormitory above, the cloister, and the monastic church with St Vincent’s chapel. THE AUGUSTINIAN FRIARS. The Augustinian friars (often called 'Austins' in England) have a traditional link with St Augustine of Hippo in North Africa, who lived 354-430 AD. Augustine had a Christian mother, a pagan father – and a brilliant mind. His student days showed excesses. He prayed 'Make me chaste, but not yet'. He searched far meaning in life through philosophers. He admired Bishop Ambrose's oratory, but not his Christian message. Then came a conversion experience in 386 AD. He had been reading St Paul's epistles. In a garden one day he seemed to hear a child's voice saying 'Tolle lege’ (Take up and read). He chanced on Romans 13: 12- 14 'Give up unrighteous acts ……..' and became a Christian. From this expenience derives the Augustinian logo showing a Bible which is afire, a heart pierced by an arrow which transfixes it to that Bible, and the phrase 'Tolle liege'. -

Clare, Suffolk: Book Iv Clare Parish Church

CLARE SUFFOLK Book IV Clare Parish Church CLARE, SUFFOLK: BOOK IV CLARE PARISH CHURCH INTRODUCTION. Daniel Defoe (1659-1731), author of the book Robinson Crusoe, visited Clare on his travels and says of it 'a poor town and dirty, the streets being unpaved. But it has a good church'. His last sentence was correct. Clare’s church can claim to have a place among the large and beautiful churches for which East Anglia is renowned. I leave open the question whether the street cleaners of the day were up to standard, but its buildings as seen today certainly cannot require the word ‘poor’. Many of them are described in Books I and II (Clare A-Z and The old streets of Clare and their buildings). Among old buildings described there are some which have been related to the church - the nearby old priest's house known now as The Ancient House; its one time successor as a vicarage across the road, Sigors, now also superseded as a vicarage; and the Guildhall from which guilds processed into the church through the same west door which is still used on special occasions today. I have tried to write for ordinary people so have inserted explanations which may be unnecessary for those who are keen explorers of churches but may prove helpful to the ordinary reader - including, perhaps, young people still at school. With this in mind I have also woven in fuller explanations of some features which are common to most churches, so in some sense the book widens out from being an account simply of Clare parish church into an introduction to churches in general.