This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading, Because of Love by Andrea Pagnes (Vestandpage) This

Reading, Because of Love By Andrea Pagnes (VestAndPage) This is not exactly a book review, but my humble thoughts skewed one after the other— a visceral empathic response to Franko’s life story, one of the artists who most inspired my journey through art. When someone tells you of his/her life, exposing his/her heart, every moment assumes its importance, even the most apparently banal. As we get to know a person better, there is a natural process that acts on our affective sphere. It is a mechanism mostly responsible for building friendship and respect. At least metaphorically, it can be said that the people we know and value inhabit a part of our brain. We have a copy of them stored in our memory: not an exact reproduction but series of images valid enough to stimulate our intellect and emotional intelligence. Some books offer very concentrated social information. They are to our social interests like fresh water is to the part of our brain when we are thirsty. For readers who are concerned with anything that has social and causal implications, those books are there to satisfy these interests. They stimulate reflection. Not all books, of course, but above all good essays and novels, and those with the focus on a single character, biographies and autobiographies. I always feel a certain fascination when an author of a book unlocks the doors of his/her world through an uncompromised way of writing. It is like receiving an open invitation to enter inside a place once kept secret and share what is there to be found, and so to imagine, mirror, recognise. -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

ON PAIN in PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das

BEARING WITNESS: ON PAIN IN PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London, 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Jareh Das hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19th December 2016 2 Acknowledgments This thesis is the result of the generosity of the artists, Ron Athey, Martin O’Brien and Ulay. They, who all continue to create genre-bending and deeply moving works that allow for multiple readings of the body as it continues to evolve alongside all sort of cultural, technological, social, and political shifts. I have numerous friends, family (Das and Krys), colleagues and acQuaintances to thank all at different stages but here, I will mention a few who have been instrumental to this process – Deniz Unal, Joanna Reynolds, Adia Sowho, Emmanuel Balogun, Cleo Joseph, Amanprit Sandhu, Irina Stark, Denise Kwan, Kirsty Buchanan, Samantha Astic, Samantha Sweeting, Ali McGlip, Nina Valjarevic, Sara Naim, Grace Morgan Pardo, Ana Francisca Amaral, Anna Maria Pinaka, Kim Cowans, Rebecca Bligh, Sebastian Kozak and Sabrina Grimwood. They helped me through the most difficult parts of this thesis, and some were instrumental in the editing of this text. (Jo, Emmanuel, Anna Maria, Grace, Deniz, Kirsty and Ali) and even encouraged my initial application (Sabrina and Rebecca). I must add that without the supervision and support of Professor Harriet Hawkins, this thesis would not have been completed. -

Abecadło Muzeum Jerke

Sztuka w Polsce i Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej „ „Szum nr 19 25,00 PLN (w tym 5% VAT) zima 2017 – wiosna 2018 ISSN 2300-3391 Otwarte Triennale Dominika Olszowy OFF-Biennale Real Nazis Abecadło Muzeum Jerke POLSKA AWANGARDA I SZTUKA WSPÓŁCZESNA Johannes-Janssen-Straße 7 45657 Recklinghausen, Germany www.museumjerke.com Krzysztof Wodiczko Żywe obrazy Otwarcie: czwartek, 7 grudnia 2017, godz. 19 Wystawa czynna: od 8 grudnia do 23 grudnia 2017 i od 3 stycznia do 13 stycznia 2018 WWW.MCK.KRAKOW.PL od wtorku do soboty, w godz. 12–19 ul. Franciszkańska 6 Lokal przy ul. Franciszkańskiej 6 w Warszawie jest 00-214 Warszawa Projekt wykorzystywany na cele kulturalne przez Fundację www.fundacjaprofile.pl współfinansuje Profile dzięki pomocy Miasta Stołecznego [email protected] m.st. Warszawa Warszawy – dzielnicy Śródmieście Patroni medialni: 10.11 – 30.12.2017 JEREMY DELLER Ryszard Kisiel, 1985/1986, kolekcja QAI QAI/CEE Karol Radziszewski 11 listopada 2017 - 6 stycznia 2018 BITWA O BATTLE OF ORGREAVE Gdańska Galeria Miejska 2 kuratorka / curator: godziny otwarcia / Dofinansowano ze środków Ministra Gdańsk City Gallery 2 Patrycja Ryłko openning hours: Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego ul. Powroźnicza 13/15 wt. - nd. 12.00 - 19.00 / wernisaż / openning: tue - sun noon - 7:00 P.M. wstęp wolny / free admission 10.11.2017 godz. 19.30 / 7:30 P.M. www.ggm.gda.pl www.centrala-space.org.uk • Birmingham, UK Magdalena Morawik z Wydziału Sztuki Mediów otrzymała główną nagrodę wystawy Coming Out – Najlepsze Dyplomy Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie za pracę Środkowa szarość. Nagrodą jest sfinansowanie przygotowania indywidualnej wystawy za rok w galerii Salon Akademii. -

AMELIA G. JONES Robert A

Last updated 4-15-16 AMELIA G. JONES Robert A. Day Professor of Art & Design Vice Dean of Critical Studies Roski School of Art and Design University of Southern California 850 West 37th Street, Watt Hall 117B Los Angeles, CA 90089 USA m: 213-393-0545 [email protected], [email protected] EDUCATION: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES. Ph.D., Art History, June 1991. Specialty in modernism, contemporary art, film, and feminist theory; minor in critical theory. Dissertation: “The Fashion(ing) of Duchamp: Authorship, Gender, Postmodernism.” UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA, Philadelphia. M.A., Art History, 1987. Specialty in modern & contemporary art; history of photography. Thesis: “Man Ray's Photographic Nudes.” HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge. A.B., Magna Cum Laude in Art History, 1983. Honors thesis on American Impressionism. EMPLOYMENT: 2014-present UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, Roski School of Art and Design, Los Angeles. Robert A. Day Professor of Art & Design and Vice Dean of Critical Studies. 2010-2014 McGILL UNIVERSITY, Art History & Communication Studies (AHCS) Department. Professor and Grierson Chair in Visual Culture. 2010-2014 Graduate Program Director for Art History (2010-13) and for AHCS (2013ff). 2003-2010 UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER, Art History & Visual Studies. Professor and Pilkington Chair. 2004-2006 Subject Head (Department Chair). 2007-2009 Postgraduate Coordinator (Graduate Program Director). 1991-2003 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, RIVERSIDE, Department of Art History. 1999ff: Professor of Twentieth-Century Art and Theory. 1993-2003 Graduate Program Director for Art History. 1990-1991 ART CENTER COLLEGE OF DESIGN, Pasadena. Instructor and Adviser. Designed and taught two graduate seminars: Contemporary Art; Feminism and Visual Practice. -

The Efficacy of Awkwardness in Contemporary Participatory Performance

The Efficacy of Awkwardness in Contemporary Participatory Performance Daniel Oliver PhD Drama Queen Mary University of London Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Required statement of originality for inclusion in research degree theses I, Daniel Oliver confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Daniel Oliver Date: 06/01/2015 Details of collaboration and publications: Oliver, Daniel, ‘Car Crashes, the Social Turn, and Glorious Glitches in David Hoyle’s Performances’ <http://liminalities.net/8-3/carcrashes.pdf> [accessed 6 January 2015] Oliver, Daniel, ‘Getting Involved with the Neighbour’s Thing: Žižek and the Participatory Performance of Reactor (UK), in Žižek and Performance, ed. -

Tantalising Glimpses: a LADA Study Room Guide on Fat Charlotte Cooper

Tantalising Glimpses: A LADA Study Room Guide on Fat Charlotte Cooper LADA Study Room Guides As part of the continuous development of the Study Room we regularly commission artists and thinkers to write personal Study Room Guides on specific themes. The idea is to help navigate Study Room users through the resource, enable them to experience the materials in a new way and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across. All Study Room Guides are available to view in our Study Room, or can be viewed and/or downloaded directly from their Study Room catalogue entry. Please note that materials in the Study Room are continually being acquired and updated. For details of related titles acquired since the publication of this Guide search the online Study Room catalogue with relevant keywords and use the advance search function to further search by category and date. Cover Image: Matthew See from the Fattylympics in 2012 depicting a non- competitive event called Spitting on the BMI Chart. You can find out more in Charlotte's book: Fat Activism: A Radical Social Movement. Cover Design: Ben Harris, 2020 Tantalising Glimpses: A LADA Study Room Guide on Fat Charlotte Cooper Contents • Introduction o About Me o Why I Love the Study Room o How I came to write this Study Room Guide o Assumptions and Limitations o Language § Jargon • Background o Five reasons why Live Artists should care about fat o Why fat Live Art is hard to find o Navigating the Study Room if you are fat • Suggested Reading and Viewing o Activism o Ambiguity o Clubbers o Contemporaries o Fatphobia o Fodder o Founding Figures o Invisibility o Other Study Room Guides and LADA publications o Tantalising Glimpses • The Missing Study Room • Last Word • Appendix Introduction Hello and welcome. -

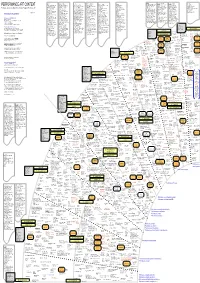

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

The Photoperformer the Performance of Photography As an Act of Precarious Interdependency

The PhotoPerformer The Performance of Photography as an Act of Precarious Interdependency Manuel Vason University for the Creative Arts Thesis submitted for the partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2019 Abstract This PhD by Publication explores Manuel Vason’s art practice at the intersections of photography and performance culminating in his development of the PhotoPerformer. Vason formulates the interdependency between the two art forms as a reflexive collaboration with the Other and as an evolving methodology which leads to a collaborative transformation of photography through performance. Vason questions the fixity of photography – symbolized by ‘the frame’ – as an ideological dispositive of power and control that distances subject and object and enforces a unique, absolute and finished perspective. Considering photography in relationship to performance allows him to comprehend the medium through theories of differentiation. He conceives the medium not as a practice of reproduction that treats images as copies of reality but rather as a process of alteration that takes place when the live image is transformed into a photographic image. Photography constantly produces new documentation of performances intending to give a stable identity to ephemeral actions. Yet, Vason’s performative practice questions the authority of those documents. While photography offers to performance a decisive time through which to record and identify the flux of its actions, performance encourages a focus on the photographic action to overcome the fixity of the photograph. Vason posits a methodological approach that allows both art forms to be in constant dialogue and confrontation, transforming their limitations into potentiality for creative expansion. -

Franko B and the Agitation of the Flesh.Pdf

Paper prepared for The Fourth Euroacademia International Conference Identities and Identifications: Politicized Uses of Collective Identities Venice, Italy 4 – 5 March 2016 This paper is a draft Please do not cite or circulate Franko B and the Agitation of the Flesh An Investigation into the Aesthetic, Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Franko B’s Open, Fragmented and Bleeding Body Alice Hoad University of Bristol Abstract Franko B opens up his body. He opens it up again and again. He bleeds. It is unbearable. It is beautiful. We are in awe. Why does he do this? What does it mean to render the body open and vulnerable? What does a transgression of the corporeal boundaries of the human body mean for our social, cultural and political identities? This paper will explore the cultural significance of the open, fragmented and bleeding body, drawing in particular on the history of Christian theology, iconography and ritual bloodletting, and examining the work of Italian-born performance artist Franko B. Key words: Franko B, performance, body, Christianity, iconography This paper will analyse the performative and object-based works of the Italian-born performance artist Franko B, in order to interrogate the position of the symbolically charged open body in Western visual culture. Franko was trained at both Camberwell and Chelsea art schools in the 1980s and is now an internationally acclaimed performance artist whose work spans a variety of media: from drawing and installation to embroidery and performance. He gained notoriety for his controversial bloodletting performances in the 1990s, in which he explored the aesthetic and performative potential of the act of bleeding, drawing on elements of both primitive ritual and Christian iconography. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Previously Published Works

UC Riverside UC Riverside Previously Published Works Title Critical Tears Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/87m1f13t ISBN 978-0910663670 Author Doyle, J Publication Date 2005 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California It is hard to have feelings in museums, and it is especially hard to cry. When we do, we tend to cry differently from the way we cry at the movies, or when we are alone with a book-if we cry at all it is with less abandon and, often, with mixed feelings. In this sense museums are perhaps a little like schools: both are spaces in which we encounter culture, usually on someone else's terms. When an artist successfully overrides the self-con- sciousness and the inhibitions that settle on us in places like galleries and classrooms, it comes as a shock: find- ing ourselves overwhelmed with actual feeling-finding ours elves cryLng,laughing, aft aid, dis gusted, aroused, outraged-can leave us feeling a bit naked. The last time this happened to me was in zoo3. As part of the Tate Modern s April symposium on Live Art-on the w-ork of performance artists like Guillermo Gomez-Pefla, la Ribot, Ron Athey, and Marina Abramovii-the body artist Franko B. staged a performance called I Miss You! in the London museum's cavernous Turbine Hall. In this piece, naked, covered in white body paint, Franko B. walks a length of canvas. He is lit up on either side from the floor by fluorescent tubes, and bleeds from catheters in his arms that hold his veins open as he slowly and ceremoniously rvalks the length of the canvas toward a bank of photogra- phers at its base. -

To Be Generative In Solidarity Rather Than Creative In Solitude

GOLEM To be generative in solidarity rather than creative in solitude -Francesco Kiais, curator GOLEM - To be generative in solidarity rather than creative in solitude is an online collective performance event. Through this artistic action and our ongoing initiative for the creation of a solidarity fund for the decentralized production of medical protective equipment in Athens, as artists we stand by local groups to limit the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Our initiative to develop a blockchain application that brings together decentralized local supply chains, empowering individuals, and smaller communities to take action during the Covid-19 crisis and beyond, was recently awarded in the international ConsenSys Health STOP COVID-19 Hackathon, that brought together more than 500 participants from over 70 countries, with the support of over 50 healthcare and life sciences professionals. https://consensyshealth.com/news/consensys-health-announces-winners-of-the-stop-covid-19-hackat hon/ The artistic event GOLEM - To be generative in solidarity rather than creative in solitude will be symbolically realized as a collection of different performative actions taking place in spaces chosen by the artists, but being transmitted and displayed simultaneously online. The audience will be free to move around in the virtual “rooms” of live or recorded performances. The virtual exhibition space will open to the public on June 5, with the vernissage at 18.00 GMT+3, which will be a presentation of the guests’ of honor participating artworks. The collective action of the transmission of the live performances will begin at 19.30. On June the 6th and 7th the virtual exhibition space will be open to the public where an archive of the participating works will be presented.