Transformation and Affirmative Action in South African Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandela Script Second Draft Revised (2)

Untitled Mandela Script (aka "The Human Factor") by ANTHONY PECKHAM (Based on material by JOHN CARLIN) Revelations Entertainment Second Draft Mace Neufeld Productions 5/22/07 "Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, the power to unite people that little else has ... It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers." Nelson Mandela Untitled Mandela Script EXT. ALL-WHITE HIGH SCHOOL, WESTERN CAPE - DAY A big, rich, powerhouse all-white high school located near the freeway into Cape Town. The RUGBY FIELDS are immaculate. FIFTEEN YEAR OLD BOYS in striped rugby jerseys train with total intensity under the critical eye of the COACH. Right ACROSS THE BOUNDARY FENCE from the rugby fields is an area of WASTE LAND leading up to the freeway. There, BLACK AND “COLORED” (MIXED-RACE) BOYS of the same age play a loose game of soccer with a tennis ball. Most of them have bare feet and threadbare, dirty clothes, most of them are noticeably smaller and skinnier than the white boys. Two cultures, separated by more than the high boundary fence. SUPER TITLE: SOUTH AFRICA, FEBRUARY 11, 1990 A COMMOTION ON THE FREEWAY intrudes on the soccer game. Horns honking, cars pull over onto the shoulder, people jump out. EXT. FREEWAY - DAY Lead by police motorbikes, then patrol cars, a white Mercedes approaches, heading towards Cape Town. Whoever is in the Mercedes has stopped traffic. EXT. ALL-WHITE HIGH SCHOOL, WESTERN CAPE - DAY The soccer players abandon their game and run for the freeway, whistling and shouting. -

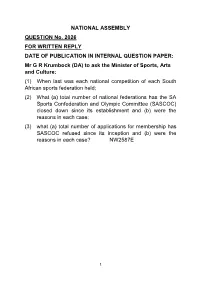

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 for WRITTEN REPLY

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 FOR WRITTEN REPLY DATE OF PUBLICATION IN INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: Mr G R Krumbock (DA) to ask the Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture: (1) When last was each national competition of each South African sports federation held; (2) What (a) total number of national federations has the SA Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (SASCOC) closed down since its establishment and (b) were the reasons in each case; (3) what (a) total number of applications for membership has SASCOC refused since its inception and (b) were the reasons in each case? NW2587E 1 REPLY (1) The following are the details on national competitions as received from the National Federations that responded; National Federations Championship(s) Dates South African Youth Championships October 2019 Wrestling Federation Senior, Junior and Cadet June 2019 Presidents and Masters March 2019 South African South African Equipped Powerlifting Championships 22 February 2020 Powerlifting Federation - Johannesburg Roller Sport South SA Artistic Roller Skating 17 - 19 May 2019 Africa SA Inline Speed skating South African Hockey Indoor Inter Provincial Tournament 11-14 March 2020 Association Cricket South Africa Proteas (Men) – Tour to India, match was abandoned 12 March 2020 without a ball bowled (Covid19 Impacted the rest of the tour). Proteas (Women)- ICC T20 Women’s World Cup 5 March 2020) (Semifinal Tennis South Africa Seniors National Competition 7-11 March 2020 South African Table Para Junior and Senior Championship 8-10 August 2019 Tennis Board -

11TOIDC COL 21R1.QXD (Page 1)

OID‰‰†KOID‰‰†OID‰‰†MOID‰‰†C The Times of India, New Delhi, Saturday,October 11, 2003 Ali presents book on his life Beckham opposed boycott Hewitt skips rest of season Raising his fists and striking a fighting pose, England football captain David Beckham begged Former World No. 1 Lleyton Hewitt has withdrawn Muhammad Ali greeted an adoring crowd at the teammate Gary Neville not to lead a boycott of the from all remaining ATP events this year in order to Frankfurt book fair on Thursday who cheered on side’s crucial Euro 2004 qualifier against Turkey in concentrate on the Davis Cup final. It means He- the former heavyweight champ as he presented protest the axing from the squad of Rio Ferdinand, witt will miss next week’s Madrid Masters, along a monumental book chronicling his life. The Sun newspaper reported on Friday. with Guillermo Coria and David Nalbandian. Jarno Trulli fastest in first qualifying for Japanese GP It just doesn’t seem to be real to me at the moment. Haydonnit! Super Matt — Kellie Hayden, wife of Matthew NZ need 18 to breathe Reuters SPORTS DIGEST blasts 380, eclipses Lara By Lionel Rodricks Reuters TIMES NEWS NETWORK Perth: Australia batsman Matthew Green cap when the record was bro- Hayden wiped Brian Lara’s individual ken.’’ Ahmedabad: The first Test Test-scoring record from the history The Australian was finally caught at match between India and books with a spectacular innings of 380 deep square-leg by Stuart Carlisle off New Zealand is tantalisingly in the first Test against Zimbabwe on Trevor Gripper for 380 shortly after tea. -

Sport, Politics and Black Athletics in South Africa During the Apartheid Era Sociology Provides an Additional Dynamic Sub-Theme with Strong Contemporary Relevance

Pieter Labuschagne Professor and Head of SPORT, POLITICS AND BLACK Department, Department ATHLETICS IN SOUTH AFRICA of Political Sciences, University of South Africa. DURING THE APARTHEID ERA: [email protected] A POLITICAL-SOCIOLOGICAL DOI: https://dx.doi.org/ PERSPECTIVE 10.18820/24150509/ JCH41.v2.5 Abstract ISSN 0258-2422 (Print) ISSN 2415-0509 (Online) The article examines the relationship between sport and politics in Journal for South Africa from a political-sociological perspective, with a specific Contemporary History focus on the status of black athletics in apartheid South Africa. The 2016 41(2):82-104 narrower focus aims to outline how white civil society and the National © UV/UFS Party government utilised athletics as a mechanism to enforce the policy of separateness/apartheid in the South African society. In the process, white dominated political structures and centralised political processes were used to dominate and regulate black athletics in South Africa (1894-1976). The structures and dynamics of black athletics were, for more than a century, manipulated and dictated for political and related reasons. The manipulation took place in three broad identifiable periods, namely: 1884-1960 – the period of “informal” segregation, when the national body, provinces and clubs used race as a mechanism to enforce cleavages in society. The second period stretches from 1960- 1976, when the National Party adopted a more assertive direct role to enforce their sports policy. The last period, between 1976 and 1992, signified another direction change, when government stepped back and only set the broader framework for the regulation of athletics in South Africa. In each of the periods, the politics-sport power relationship will be explained in relation to the regulation of black athletics in the country. -

Surviving to Thriving Mental Toughness

SURVIVING TO THRIVING MENTAL TOUGHNESS DR STEVE HARRIS Charles Darwin reputedly said that the strongest of the species will survive and the most adaptive will thrive. My research and experience confirm that improved mental toughness will provide you with a tailwind towards thriving. If you are already thriving, it will keep you moving ahead. 1 Published by Dr Steve Harris [email protected] www.steveharris.co.za Copyright © 2019 Steve Harris ISBN: 978-0-620-72116-5 Surviving to Thriving - Mental Toughness The 2013 hard cover edition titled Mental Toughness – Mastering Your Mind presented conclusions from my PhD combined with personal experiences. Since then I have released several revised, PDF editions adding new knowledge. This edition is titled: Surviving to Thriving - Mental Toughness 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ....................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................... 5 1 Why Surviving to Thriving? .............................................. 6 2 Surviving to Thriving Guide............................................ 19 3 A definition of Mental Toughness ................................... 30 5 Concentration................................................................... 37 6 Composure ....................................................................... 54 7 Controlled Aggression ..................................................... 79 8 Confidence ...................................................................... -

Soccer/Football: Rugby: Cricket: Springbok Partisan / South African

Sport in South Africa is practically a religion. The spectators come mostly to see football, rugby and cricket not only to watch the game but also to catch the atmosphere. South Africans are extremely passionate with sports. It occupies all medias and newspapers. Soccer/Football: Rugby: Football or soccer in South Africa is the This is a great passion in most popular game. It became the center of South Africa and an equivalent the non-racial sport movement. Its of a religion in the “whites” traditional supporter base is principally of South Africa. The country is in the black community. In 1991 it became usually good and competitive at the first sport to become unified and rugby, so if the national team, captivated the hearts of all South the “Springboks”, lose a game, Africans. The country’s national team, supporters are depressed for at affectionately nicknamed “Bafana least a week. They consider Bafana”(=“The Boys”) was qualified for the they must win every game except 1998 and 2002 World Cup Finals. against the New Zealand team, the “All Blacks”, because they have a great respect for them. The 1995 Rugby World Cup was played in South Africa and won Cricket: by the “Springboks”. The greatest triumph came when Makhaya Ntini became the first black player Nelson Mandela put on the number six jersey of Francois of the national team, “The Proteas”, in Pienaar (a South African 1998. South African cricket had a major player) to present the cup. It hitting in 2000 when the captain of the was a major period of the team, Hansie Cronje (a famous player of history of South African rugby cricket), was discovered to have accepted which had been for a long time money to lose matches. -

Foundation Overview 2016 Contents

FOUNDATION OVERVIEW 2016 CONTENTS 5 ABOUT LAUREUS 6 CHAIRMANS LETTER 7 GLOBAL REPORT - ANDY GRIFFITHS 8 MERCEDES-BENZ LETTER 10 LAUREUS TRUSTEES 16 MERCEDES-BENZ BREAKFAST SERIES 18 MERCEDES-BENZ TROPHY SERIES 20 LAUREUS AWARDS 32 LAUREUS PROJECTS 72 LAUREUS AMBASSADORS 2 LAUREUS SPORT FOR GOOD SOUTH AFRICA ABOUT LAUREUS THE LAUREUS WORLD SPORTS AWARDS Laureus’ core concept is simple, brilliant and The Best in Sport daunting: to create global awards that recognise The Awards celebrate and honour the most remarkable the achievements of today’s sporting heroes; achievements of men, women and teams from the world to bring sportspeople together; united in of sport within a calendar year. Proceeds from the Laureus achievement but divided by sporting code. Once World Sports Awards directly benefit and underpin the work of the Laureus Sport for Good Foundation. that community is brought together, putting to work their reach and the support and investment of Laureus’ Founding Patrons and Partners, it “SPORT HAS THE POWER creates a powerful message that can help social projects around the world who use sport as a tool for social change. That message, simply, is THE LAUREUS WORLD SPORTS ACADEMY Laureus Sport for Good. The Best of Sport “Using the power of sport as a The Academy is the ultimate sports jury who selects the winners of the Laureus World Sports Awards. The Members tool for social change.” of the Academy also volunteer their time to act as global ambassadors for the Laureus Sport for Good Foundation. Laureus Ambassadors are sports men and women who are The Laureus Sport for Good Foundation’s goal is supporting the Academy by inspiring the next generation. -

Momentum Health Attakwas Presented by Biogen Finishers to Date (003).Xlsx

FINISHERS BY NAMES 2007 - 2018 RIDER 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Total A Eksteen 1 1 Aaron Adler 1 1 Aaron Borrill 1 1 Aaron David 1 1 Abdallah Salie 1 1 Abdul-Gameed Salie 1 1 1 1 4 Abdullah Jaffar 11 2 Abraham Meyer 11 Abrie Du Plessis 11 Abrie Fouche 111 3 Abrie Van Tonder 11 Abu Veldsman 11 Adam Foster 1 1 Adam Pike 1 1 Adam Rampf 1 1 Adam Wooldridge 1 1 Adele Drake 1 1 Adele Niemand 1 1 Adele Zurnamer 1 1 Adiel Mohamed 1 1114 Adnan Essop 1 1 Adniaan Solomon 11 Adohan Van Den Berg 1 1 Adraain Lourens 1 1 Adriaan De Bruyn 1 1 Adriaan Jansen Van Vuuren 1 1 2 Adriaan Louw 11 11 4 Adriaan Pearson 1 1 Adriaan Steyn 11 Adriaan Strauss 1 1 Adrian Cooney 1 1 Adrian De Jonge 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 7 Adrian Enthoven 11 2 Adrian Fogg 11 2 Adrian Harris 11 Adrian Haupt 112 Adrian Hegerty 1 1 Adrian Hobbs 1 1 Adrian Smit 1 1 Adrian Vardy 1 1 2 Adriano Bertoncello 1 1 Adrien Niyonshuti 1 1 AHMED ZAID Mahomed 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 7 Aidan Van Niekerk 1 1 2 Aileen Anderson 11 2 Al Botha 1 1 Alan Botten 1 1 Alan Cotton 11 2 RIDER 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Total Alan Crossley 1 1 Alan Dawson 1 1 Alan Haupt 1 1 Alan Macintosh 1 113 Alan Rees 11 2 Alan Rosewall 1 1 Alan Thomas 1 1 Alan Van Den Handel 1 1 Alan Van Schoor 1 1 Alana Smit 1 1 Alasdair Sholto-Douglas 1 1 Alastair Haarhoff 1 1 Alastair Hops 1111 4 Alastair Sellick 112 Albe Geldenhuys 1 1 2 Albert Bester 11 2 Albert Coetzee 1 1 Albert Kleynhans 11 Albert Pretorius 11 Albert Retief 1 1 2 Albert Rust 1 1 2 Albert Van Zyl 11 2 Alberto Prins 11 2 -

Forward Momentum

Forward momentum JIM TUCKER finds out what Taranaki rugby is doing to make more history: “It was the BBC - Brown, Briscoe and Carroll.” So began the front page story in the Taranaki Herald Sports Edition one Saturday in 1959. It was one of an endless string of puns the paper’s rugby writer used to chronicle extraordinary feats by Taranaki’s late-50s Ranfurly Shield holders. The monikers so playfully employed above – it could easily have been Burke, Boon and Cameron - are a distant memory for most of today’s generation. But they’re far from forgotten at Taranaki Football Rugby Union HQ in Yarrow Stadium. As the photograph of TRFU chief executive Mike Collins shows, that great team dominates one whole wall of the meeting room, and as the union gears up to repeat last year’s win in the ITM inter-provincial rugby competition, the names of Peter Burke, Ross Brown, Kevin Briscoe, Ralph Carroll and company resonate as never before. One reason is the current team already rivals the ‘59ers on at least one measure – the number of All Blacks in its ranks While Taranaki had six at various stages between 1957 and 1960, today’s team has five, with more in the offing. It also has eight Maori All Blacks, (including captain Charlie Ngatai, also an All Black), and two in the Junior All Blacks. Not that any of this is particularly at the forefront He says the academy managers, Willy Rickards of Mike Collins’ mind as he and his team prepare and Adam Haye, spotted Vaeno during some high for the ITM Cup season, which began with a school first fifteen games. -

Pakistan Take Charge of Decisive Test

The Island, Tuesday 31st January, 2006 India poses biggest threat to hosts at Youth World Cup by Rex Clementine host all Sri Lanka’s first round Kaif beat the hosts to win the tions from the supporters put games. 2000 edition of the competi- the young players under Neighbour India poses the Two teams will qualify for tion at the SSC. additional pressure? biggest challenge to hosts Sri the quarter-finals of the com- Sri Lanka played India in “Conditions here are Lanka in the Under-19 Cricket petition from each group and the Afro-Asian Cup last year going to help us obviously World Cup that gets under- if Sri Lanka go through they in India and were beaten in and it’s an advantage. With way next week in Colombo. will probably meet either the the final, but apparently have expectations being so high, Sri Lanka’s captain Angelo West Indies, Australia or addressed key areas that did- the pressure can build, but Mathews, coach Sumithra South Africa. n’t go right for them in that looking positively it will help Warnakulasuriya and manag- “The Indian game is going tournament. us to do even better,” er Ashley de Silva addressed to be the toughest for us. They “During the Afro-Asia Mathews said. the media in Colombo, yester- are a good side, but having Cup fielding was our main The hosts are also the most day. said that, we’ll be approach- concern. We have done a lot prepared team in the compe- Sri Lanka are drawn in ing all games with the same of hard work towards rectify- tition having toured Pakistan, Group ‘C’ in the two week level of intensity,” Mathews ing the shortcomings,” Bangladesh and England. -

ICC U19 Cricket World Cup 2020

MEDIA GUIDE Version 3 / January 2019 2 The ICC would like to thank all its Commercial Partners for their support of the ICC U19 Cricket World Cup South Africa 2020. ICC U19 CRICKET WORLD CUP 3 I’d like to welcome all members WELCOME of the media here in South Africa and those around the world who ICC CHIEF EXECUTIVE will be covering the ICC U19 Cricket World Cup 2020. This is the second time that South Africa has On behalf of the ICC, I would like to take this hosted the tournament which is close to the opportunity to thank Cricket South Africa, its staff, hearts of all of us at ICC and is considered a very ground authorities and volunteers in helping us important event on our calendar. It provides organize this important event. I would also like players with an unrivaled experience of global to thank our commercial and broadcast partners events and a real flavour of international cricket for their support in making our events so special at senior level, while cricket fans around the world and taking them to the widest possible audience. can watch tomorrow’s stars in action either in A word of appreciation is likewise due to my person, on television or via the ICC digital channels. colleagues at the ICC, who have worked so hard in preparation for this event. A host of past and present stars have come through this system and the fact that a number of the I would also like to thank all members of the world’s best current players including Virat Kohli, media for your continued support of this event, Steve Smith, Joe Root, Kane Williamson, Sarfraz whether you are here in person or following from Ahmed and Dinesh Chandimal have all figured in your respective countries around the world, the past ICC U19 World Cups, demonstrates the calibre coverage you drive is crucial to the future success of cricketers we can expect to see during this event. -

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD Registered address: Block A, Equity Park 257 Brooklyn Road Brooklyn Pretoria 0181 Postal address: P O Box 1556 Brooklyn Square Pretoria 0075 Telephone: +27-12-362 0306 Fax: +27-12-362 2590 Auditors: Auditor-General Bankers: ABSA Nedbank First National Bank Rand Merchant Bank Standard Corporate Merchant Bank NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 Mr. A Erwin Minister of Trade and Industry Report of the National Lotteries Board for the period 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2002. It is my singular honour to submit the Annual Report of the National Lotteries Board and the National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund. J A Foster Chairman 2 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 CONTENTS PAGE NO. Chairperson’s Report 4 National Lotteries Board: 13 Report of the Auditor-General 14 Balance Sheet 15 Income Statement 16 Statement of Changes in Equity 17 Cash Flow Statement 18 Notes to the Financial Statements 21 National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund: 27 Report of the Auditor-General 28 Balance Sheet 29 Income Statement 30 Statement of Changes in Equity 31 Cash Flow Statement 32 Notes to the Financial Statements 33 Beneficiaries of Good Cause monies 36 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 3 CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The support of South Africans for the National Lottery in the past two years has been phenomenal. Because of this support, the funds raised by the National Lottery for good causes are making a difference to the lives of the people of South Africa through the promotion of charitable work, the arts, culture, national heritage, sport and recreation.