Melissa Giles Exegesis (PDF 910Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

CONTENTS Table of Contents Messages from the President and CEO . 3 Organisational Structure . 4 ACON – the 2001-02 year in review. 5 Developing our capacity Sydney, Positive Living Centre (PLC), Western Sydney . 6 Illawarra, Northern Rivers and Tweed Valley Outreach . 7 Hunter, Mid North Coast Outreach and Central Coast Outreach. 7 Strengthening our communities . Fun & Esteem, Mature Aged Gays (MAG) . 8 Same Sex Attracted Young Women Project . 8 Sex Workers’ Outreach Project (SWOP), Asian Project . 9 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Project . 9 Improving our communities’ health HIV Living, HIV Women’s Services and Health Promotion . 10 Gay Men’s Health, Lesbian Health . 11 Improving services to individuals Treatments and Vitamins, Housing Project. 12 Community Support Network (CSN) . 12 Counselling, Enhanced Care Project . 13 Family Support, Injecting and Other Drug Use Project . 13 Strengthening our advocacy ACON Advocacy, Lesbian and Gay Anti-Violence Project (AVP) . 14 AIDS Awareness, HIV Visibility . 15 Strengthening our partnerships Sharing Knowledge . 16 Community Support and Events . 17 Partners, Sponsors and Supporters . 18 Staff and Volunteers . 19 Expenditure . 20 Treasurer’s Report . 21 Members of the Board Report. 22 Financial Report . 25 Acknowledgment and Credit The Board and management of ACON would like to acknowledge and thank the staff and volunteers of our organisation for their commitment and dedication, and for the wonderful work they continue to do for our clients and communities. We would also like to acknowledge -

Latest Financials

Page 1 CONTENTS - Acknowledgment of country and partnerships - President's Report - Treasurer's Report - Station Manager's Report - Year at a glance - The Stats - Financial Report - 2018 AGM Meeting Minutes Page 2 We would like to start my report with acknowledging the traditional owners of the land that we meet, the station resides, and that we broadcast from. We pay our respects to the Yugara and Turrbal people and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. Page 3 PRESIDENT'S REPORT Hi everyone and welcome to our AGM. As you will have been aware there have been huge changes at the Station and I would like to just take a few moments to put things into perspective. We have lived through what is probably the fastest changing dynamic the world has ever seen and the momentum is growing. When I grew up all we had was radio and we listened faithfully to all the programmes as there was only one Station – the BBC in England and the ABC here. I worked at the BBC in the 50s and we had the huge tapes that I recognised when I came to 4RHP about 12 years ago. My first training on a computer was in the mid 70s and that was at one of the first companies to use computers. All very strange to us. The machines were big and bulky and the computer had a whole room to itself. We slowly got used to that and when I opened my own business in the early 80s we had home computers and can you believe it a mobile phone that was huge. -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS and CONTENT LIST - Content for Broadcast on Your Station

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Content for broadcast on your station May 2019 All times AEST/AEDT CRN PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Table of contents FLAGSHIP PROGRAMMING Beyond Zero 9 Phil Ackman Current Affairs 19 National Features and Documentary Bluesbeat 9 Playback 19 Series 1 Cinemascape 9 Pop Heads Hour of Power 19 National Radio News 1 Concert Hour 9 Pregnancy, Birth and Beyond 20 Good Morning Country 1 Contact! 10 Primary Perspectives 20 The Wire 1 Countryfolk Around Australia 10 Radio-Active 20 SHORT PROGRAMS / DROP-IN Dads on the Air 10 Real World Gardener 20 CONTENT Definition Radio 10 Roots’n’Reggae Show 21 BBC World News 2 Democracy Now! 11 Saturday Breakfast 21 Daily Interview 2 Diffusion 11 Service Voices 21 Extras 1 & 2 2 Dirt Music 11 Spectrum 21 Inside Motorsport 2 Earth Matters 11 Spotlight 22 Jumping Jellybeans 3 Fair Comment 12 Stick Together 22 More Civil Societies 3 FiERCE 12 Subsequence 22 Overdrive News 3 Fine Music Live 12 Tecka’s Rock & Blues Show 22 QNN | Q-mmunity Network News 3 Global Village 12 The AFL Multicultural Show 23 Recorded Live 4 Heard it Through the Grapevine 13 The Bohemian Beat 23 Regional Voices 4 Hit Parade of Yesterday 14 The Breeze 23 Rural Livestock 4 Hot, Sweet & Jazzy 14 The Folk Show 23 Rural News 4 In a Sentimental Mood 14 The Fourth Estate 24 RECENT EXTRAS Indij Hip Hop Show 14 The Phantom Dancer 24 New Shoots 5 It’s Time 15 The Tiki Lounge Remix 24 The Good Life: Season 2 5 Jailbreak 15 The Why Factor 24 City Road 5 Jam Pakt 15 Think: Stories and Ideas 25 Marysville -

Reclink Annual Report 2017-18

, Annual Report 2017-18 Partners Our Mission Respond. Rebuild. Reconnect. We seek to give all participants the power of purpose. About Reclink Australia Reclink Australia is a not-for-profit organisation whose aim is to enhance the lives of people experiencing disadvantage or facing significant barriers to participation, through providing new and unique sports, specialist recreation and arts programs, and pathways to employment opportunities. We target some of the community’s most vulnerable and isolated people; at risk youth, those experiencing mental illness, people with a disability, the homeless, people tackling alcohol and other drug issues and social and economic hardship. As part of our unique hub and spoke network model, Reclink Australia has facilitated cooperative partnerships with a membership of more than 290 community, government and private organisations. Our member agencies are committed to encouraging our target population group, under-represented in mainstream sport and recreational programs, to take that step towards improved health and self-esteem, and use Reclink Australia’s activities as a means of engagement for hard to reach population groups. Contents Our Mission 3 State Reports 11 About Reclink Australia 3 AAA Play 20 Why We Exist 4 Reclink India 22 What We Do 5 Art Therapy 23 Delivering Evidence-based Programs 6 Events, Fundraising and Volunteers 24 Transformational Links, Training Our Activities 32 and Education 7 Our Members 34 Corporate Governance 7 Gratitude 36 Founder’s Message 8 Our National Footprint 38 Improving Lives and Reducing Crime 9 Reclink Australia Staff 39 Community Partners 10 Contact Us 39 Notice of 2017 Annual General Meeting The Annual General Meeting for Members 1. -

Tuning in to Community Broadcasting

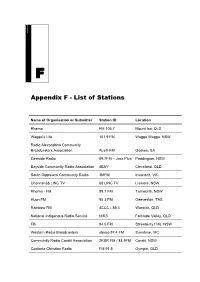

F Appendix F - List of Stations Name of Organisation or Submitter Station ID Location Rhema FM 105.7 Mount Isa, QLD Wagga’s Life 101.9 FM Wagga Wagga, NSW Radio Alexandrina Community Broadcasters Association ALeX-FM Goolwa, SA Eastside Radio 89.7FM – Jazz Plus Paddington, NSW Bayside Community Radio Association 4BAY Cleveland, QLD South Gippsland Community Radio 3MFM Inverloch, VIC Channel 68 LINC TV 68 LINC TV Lismore, NSW Rhema - FM 89.7 FM Tamworth, NSW Huon FM 95.3 FM Geeveston, TAS Rainbow FM 4CCC - 89.3 Warwick, QLD National Indigenous Radio Service NIRS Fortitude Valley, QLD FBi 94.5 FM Strawberry Hills, NSW Western Radio Broadcasters stereo 97.4 FM Sunshine, VIC Community Radio Coraki Association 2RBR FM / 88.9FM Coraki, NSW Cooloola Christian Radio FM 91.5 Gympie, QLD 180 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Orange Community Broadcasting FM 107.5 Orange, NSW 3CR - Community Radio 3CR Collingwood, VIC Radio Northern Beaches 88.7 & 90.3 FM Belrose, NSW ArtSound FM 92.7 Curtin, ACT Radio East 90.7 & 105.5 FM Lakes Entrance, VIC Great Ocean Radio -3 Way FM 103.7 Warrnambool, VIC Wyong-Gosford Progressive Community Radio PCR FM Gosford, NSW Whyalla FM Public Broadcasting Association 5YYY FM Whyalla, SA Access TV 31 TV C31 Cloverdale, WA Family Radio Limited 96.5 FM Milton BC, QLD Wagga Wagga Community Media 2AAA FM 107.1 Wagga Wagga, NSW Bay and Basin FM 92.7 Sanctuary Point, NSW 96.5 Spirit FM 96.5 FM Victor Harbour, SA NOVACAST - Hunter Community Television HCTV Carrington, NSW Upper Goulbourn Community Radio UGFM Alexandra, VIC -

Community Participation in the Development of Digital Radio: the Australian Experience

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Spurgeon, Christina, Rennie, Ellie, & Ming Fung, Yat (2011) Community participation in the development of digital radio: The Australian experience. In Lowes, N (Ed.) Record of the Communications Policy and Research Forum 2011. Network Insight Pty Ltd, Australia, pp. 166-179. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/49677/ c First published November 2011. Copyright 2011 Network Insight Pty Ltd & C. Spurgeon, E. Rennie and Y. Fung. This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.networkinsight.org/ events/ cprf2011.html This is the published version of the following conference paper: Spurgeon, Christina L., Rennie, Elinor M., & Ming Fung, Yat (2011) Community participation in the development of digital radio : the Australian experience. -

Arn Continues to Dominate As Australia's #1 Network

ARN CONTINUES TO DOMINATE AS AUSTRALIA’S #1 NETWORK ARN - #1 National Network for five consecutive surveys Sydney - #1FM & #2FM Station & Breakfast Melbourne - #1FM Station, Breakfast, Mornings, Afternoons & the Weekend Adelaide - #1 Station, #1FM Breakfast, Mornings, Afternoons & Evenings Perth - #2 Overall Station & Breakfast Tuesday March 10th 2020 - Today’s radio ratings results for the first survey of 2020 have delivered market leaders Australian Radio Network (ARN) the dominant #1 National Network position for the fifth consecutive survey with an 18.5% share. They hold the #1FM Station and Breakfast in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide, and the #2 Overall Station and Breakfast in Perth. Results around the country include: Sydney #1 and #2 FM Station for WSFM and KIIS 1065 #1 and #2FM Breakfast for The Kyle & Jackie O Show and Jonesy & Amanda in the Morning KIIS 1065 - #1FM Breakfast for the twelfth consecutive survey – Kyle & Jackie O – on 9.9% WSFM - #2FM Breakfast – Jonesy & Amanda – up 0.6 to 9.1% WSFM - #1FM Mornings - Mike Hammond - up 0.9 to 8.5% KIIS 1065 – #2FM Drive – Will & Woody on 9.0% Melbourne #1FM Station and Breakfast for GOLD104.3 and The Christian O’Connell Breakfast Show GOLD104.3 - #1FM Station on 10.8% with 1,182,000 listeners, more than any other station GOLD104.3 - #1FM Breakfast Christian O’Connell – up 1.4% to 9.2% GOLD104.3 - #1FM - Mornings, Afternoons and the Weekend KIIS 101.1 – up 0.7 to 6.4% with 903,000 listeners KIIS 101.1 Breakfast Jase & PJ – up 0.7 to 7.1% Adelaide #1 Station Overall -

STORM KIT CHECKLIST the Brisbane City Council Notes What Should Be in Your Storm Kit, and It Includes the Following Items

STORM KIT CHECKLIST The Brisbane City Council notes what should be in your storm kit, and it includes the following items: 1. A portable battery-operated radio and torch with fresh or spare batteries and bulb 2. A list of local radio stations for emergency information 3. Candles with waterproof matches or a gas lantern 4. Reasonable stocks of fresh water and tinned or dried food 5. A first aid kit and basic first aid knowledge 6. Good supply of essential medication 7. Strong shoes and rubber gloves 8. A waterproof bag for clothing and valuables – put valuables and certificates in the bag and put the bag in a Safe place 9. A list of your emergency contact numbers 10. A car charger for your mobile phone POINTS TO REMEMBER Along with the above, there are a couple of points to remember for when a storm is just about to hit. Sometimes you have no way of avoiding being caught out when a storm approaches - it may hit your area earlier than expected or a weather forecast turns out being wrong. When it’s a situation where a storm may just be In the instance that you’re on foot when a storm a few minutes away, remember to bring inside is about to roll through, find some form of shelter any potentially dangerous outdoor objects if ASAP, but try to avoid taking shelter under you’re at home. If you’re caught driving, try trees or metal roofs. If you’re at work or in to find somewhere to park that is away another residential/commercial place, remain from creeks and high trees. -

The Magazine of the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia

NOVEMBER 2012 || The Magazine of the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia National Listener Survey Results || Radio With Pictures || Networking The News 8 10 contents President's Column ....................................................... 2 CBAA Update ............................................................... 3 National Listener Survey.............................................. 4 12 Project News ................................................................. 6 By Invitation ................................................................. 7 Networking the News ................................................... 8 Small Talk .................................................................. 10 Radio with Pictures .................................................... 12 Radio Days ................................................................. 15 Across the Sector ....................................................... 16 Station to Station ........................................................ 19 20 Making Radio ............................................................. 20 Getting the Message Across ....................................... 22 24 Out of the Box ............................................................ 24 2 The Magazine of the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia • November 2012 E CBAA H T M O Conference, R F S W IE CBX is the magazine of the D V Community Broadcasting Association an Codes, Campaigns, of Australia. W NES CBX is mailed to CBAA members and stakeholders. Subscribe -

CBF Annual Report 2018

Community Broadcasting Foundation Annual Report 2018 Contents Our Vision 2 Our Organisation 3 Community Broadcasting Snapshot 4 President and CEO Report 5 Our Board 6 Our People 7 Achieving our Strategic Priorities 8 Strengthening & Extending Community Broadcasting 9 Content Grants 10 Development & Operational Grants 14 Sector Investment 18 Grants Allocated 21 Financial Highlights 38 Cover: Sandra Dann from Goolarri Media. © West Australian Newspapers Limited. Our thanks to James Walshe from James Walshe photography for his generous support of the CBF in photographing the CBF Board and Support Team. The Community Broadcasting Foundation acknowledges First Nations’ sovereignty and recognises the continuing connection to lands, waters and communities by Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; and to Elders both past and present. We support and contribute to the process of Reconciliation. Annual Report 2018 1 Our Vision A voice for every community – sharing our stories. Wendyll Alec, host of Munda Country Music on Ngaarda Media. Annual Report 2018 2 Community media sits at the From major cities to remote communities, our grants inspire Our Values Our heart of Australian culture, people to create and support local, independent media. Our Values are the cornerstone of our community-based funding helps connect people across the country, including organisation, informing our decision-making and guiding us to Organisation sharing stories, enhancing more than 5.7 million people who tune-in to their local achieve our vision. community radio station each week. health and wellbeing and most Community-minded importantly, helping people find Through broadcasters and with the help of generous We care. -

An Ipswich Case Study: How Does Local Broadcast Media Value, Esteem and Provide Voice to a Rapidly Changing Urban Centre?

An Ipswich Case Study: How Does Local Broadcast Media value, esteem and provide voice to a rapidly changing urban centre? Doctor of Philosophy Ashley Paul Jones Graduate Diploma of Media Production Master of Arts in Media Production 2016 i ABSTRACT Radio is part of our everyday life experience in various rooms around the home, in the car and as a portable device. Its impact and connection with the local community was immediate since its inception in Australia in 1923. Radio became directly part of the City of Ipswich in 1935 with the birth of 4IP (Ipswich). Local people were avid consumers of broadcast media and recognised that, in particular, 4IP was something that they could both participate in and consume. It gave people a voice; historically 4IP broadcast local choirs, soloists, produced youth programs and generally reflected the community in which it existed. The radio station moved out of Ipswich and established itself in Brisbane during 1970s. This move resulted in a loss of a voice in the local area through broadcast radio. Similarly, the place, Ipswich City changed dramatically and is confronted with significant population growth and the emergence of an old and new Ipswich that is potentially problematic for the local council to manage. The aim is to provide a sense of localism that was strongly present in the early decades of Ipswich as evidenced by the interactions with 4IP; the identity of the two is remarkable because of their parallel flux. My thesis will provide a unique insight into the relationship between a community, that community’s membership and local radio services.