Security Council Distr.: General 21 February 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict's Complexity in Northern Mali Calls for Tailored Solutions

Policy Note 1, 2015 By Ole Martin Gaasholt Who needs to reconcile with whom? The Conflict’s Complexity in Northern Mali Calls for Tailored Solutions PHOTO: MARC DEVILLE/GETTY IMAGES While negotiations are taking place in Algiers, some observers insist on the need for reconciliation between Northern Mali and the rest of the country and particularly between Tuareg and other Malians. But the Tuareg are a minority in Northern Mali and most of them did not support the rebels. So who needs to be reconciled with whom? And what economic solutions will counteract conflict? This Policy Note argues that not only exclusion underlies the conflict, but also a lack of economic opportunities. The important Tuareg component in most rebellions in Mali does not mean that all Tuareg participate or even support the rebellions. ll the rebellions in Northern Mali the peoples of Northern Mali, which they The Songhay opposed Tuareg and Arab have been initiated by Tuareg, typi- called Azawad, and not just of the Tuareg. rebels in the 1990s, whereas many of them cally from the Kidal region, whe- There has thus been a sequence of joined Islamists controlling Northern Mali in reA the first geographically circumscribed rebellions in Mali in which the Tuareg 2012. Very few Songhay, or even Arabs, joined rebellion broke out a few years after inde- component has been important. In the Mouvement National pour la Libération pendence in 1960. Tuareg from elsewhere addition, there have been complex de l’Azawad (MNLA), despite the claim that in Northern Mali have participated in later connections between the various conflicts, Azawad was a multiethnic territory. -

Security Council Distr.: General 28 December 2020

United Nations S/2020/1281* Security Council Distr.: General 28 December 2020 Original: English Situation in Mali Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2531 (2020), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2021 and requested me to report to the Council every three months on the implementation of the resolution. The present report covers major developments in Mali since my previous report (S/2020/952) of 29 September. As requested in the statement by the President of the Security Council of 15 October (S/PRST/2020/10), it also includes updates on the Mission’s support for the political transition in the country. II. Major developments 2. Efforts towards the establishment of the institutions of the transition, after the ousting of the former President, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita on 18 August in a coup d’état, continued to dominate political developments in Mali. Following the appointment in late September of the President of the Transition, Bah N’Daw, the Vice-President, Colonel Assimi Goïta, and the Prime Minister, Moctar Ouane, on 1 October, a transition charter was issued. On 5 October, a transitional government was formed, and, on 3 December, President Bah N’Daw appointed the 121 members of the Conseil national de Transition, the parliament of the Transition. Political developments 1. Transitional arrangements 3. On 1 October, Malian authorities issued the Transition Charter, adopted in September during consultations with political leaders, civil society representatives and other national stakeholders. The Charter outlines the priorities, institutions and modalities for an 18-month transition period to be concluded with the holding of presidential and legislative elections. -

Impact De La Mise E Chance Dans La Régio

Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de République du Mali la Recherche Scientifique ------------- ----------------------- Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi Universités des Sciences, des Techniques et des Te chnologies de Bamako (USTTB) --------------- Thèse N°…… Faculté de Médecine et d’Odonto -Stomatologie Année Universitaire 2011/2012 TITRE : Impact de la mise en œuvre de la stratégie chance dans la région de Mopti : résultat de l’enquête 2011 Thèse présentée et soutenue publiquement le………………………/2013 Devant la Faculté de Médecine et d’Odonto -Stomatologie Par : M. Boubou TRAORE Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur en Médecine (Diplôme d’Etat) JURY : Président : Pr Tiéman COULIBALY Membre : Dr Alberd BANOU Co-directeur : Dr Mamadou DEMBELE Directeur de thèse : Pr Sanoussi BAMANI Thèse de Médecine Boubou TRAORE 1 DEDICACES A MA MERE : Fanta FANE Je suis fier de t’avoir comme maman Tu m’as appris à accepter et aimer les autres avec leurs différences L’esprit de tolérance qui est en moi est le fruit de ta culture Tu m’as donné l’amour d’une mère et la sécurité d’un père. Tu as été une mère exemplaire et éducatrice pour moi. Aujourd’hui je te remercie d’avoir fait pour moi et mes frères qui nous sommes. Chère mère, reçois, à travers ce modeste travail, l’expression de toute mon affection. Q’ALLAH le Tout Puissant te garde longtemps auprès de nous. A MON PERE : Feu Tafara TRAORE Ton soutien moral et matériel ne m’as jamais fait défaut. Tu m’as toujours laissé dans la curiosité de te connaitre. Tu m’as inculqué le sens du courage et de la persévérance dans le travail A MON ONCLE : Feu Yoro TRAORE Ton soutien et tes conseils pleins de sagesse m’ont beaucoup aidé dans ma carrière scolaire. -

Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in Mali

United Nations S/2016/1137 Security Council Distr.: General 30 December 2016 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2295 (2016), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2017 and requested me to report on a quarterly basis on its implementation, focusing on progress in the implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali and the efforts of MINUSMA to support it. II. Major political developments A. Implementation of the peace agreement 2. On 23 September, on the margins of the general debate of the seventy-first session of the General Assembly, I chaired, together with the President of Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, a ministerial meeting aimed at mitigating the tensions that had arisen among the parties to the peace agreement between July and September, giving fresh impetus to the peace process and soliciting enhanced international support. Following the opening session, the event was co-chaired by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, International Cooperation and African Integration of Mali, Abdoulaye Diop, and the Minister of State, Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Algeria, Ramtane Lamamra, together with the Under - Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations. In the Co-Chairs’ summary of the meeting, the parties were urged to fully and sincerely maintain their commitments under the agreement and encouraged to take specific steps to swiftly implement the agreement. Those efforts notwithstanding, progress in the implementation of the agreement remained slow. Amid renewed fighting between the Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) and the Platform coalition of armed groups, key provisions of the agreement, including the establishment of interim authorities and the launch of mixed patrols, were not put in place. -

Rapport Annuel 2016 Etat D'execution Des Activites

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT DE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DU ****************** DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE ************* Un Peuple –Un But – Une Foi AGENCE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE (AEDD) ************* PROGRAMME D’APPUI A L’ADAPTATION AUX CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES DANS LES COMMUNES LES PLUS VULNERABLES DES REGIONS DE MOPTI ET DE TOMBOUCTOU (PACV-MT) RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 PACV-MT ETAT D’EXECUTION DES ACTIVITES Octobre 2016 ACRONYMES AEDD : Agence de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable AFB : Fonds d’Adaptation CCOCSAD : Comité Communale d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Développement CLOCSAD : Comité Local d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Développement CROCSAGD : Comité Régionale d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Gouvernance et de Développement CEPA : Champs Ecoles Paysans Agroforestiers CEP : Champs Ecoles Paysans CNUCC : Convention Cadre des Nations Unies sur le Changement Climatique DAO : Dossier d’Appel d’Offres DCM : Direction de la Coopération Multilatérale DGMP : Direction Générale des Marchés Publics MINUSMA : Mission Multidimensionnelle Intégrée des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation au Mali OMVF : Office pour le Mise en Valeur du système Faguibine PAM : Programme Alimentaire Mondial PDESC : Plan de développement Economique, Social et Culturel PTBA : Plan de Travail et de Budget Annuel PACV-MT : Programme d‘Appui à l‘Adaptation aux Changements Climatiques dans les Communes les plus Vulnérables des Régions de Mopti et de Tombouctou PK : Protocole de Kyoto PNUD : Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement TDR : Termes de références UGP : Unité de Gestion du Programme RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 DU PACV-MT Page 2 sur 47 TABLE DES MATIERES ACRONYMES ............................................................................................................... -

JPC.CCP Bureau Du Prdsident

Onchoccrciasis Control Programmc in the Volta Rivcr Basin arca Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose dans la R6gion du Bassin de la Volta JOIN'T PROCRAMME COMMITTEE COMITE CONJOINT DU PROCRAMME Officc of the Chuirrrran JPC.CCP Bureau du Prdsident JOINT PROGRAII"IE COMMITTEE JPC3.6 Third session ORIGINAL: ENGLISH L Bamako 7-10 December 1982 October 1982 Provisional Agenda item 8 The document entitled t'Proposals for a Western Extension of the Prograncne in Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ssnegal and Sierra Leone" was reviewed by the Corrrittee of Sponsoring Agencies (CSA) and is now transmitted for the consideration of the Joint Prograurne Conrnittee (JPC) at its third sessior:. The CSA recalls that the JPC, at its second session, following its review of the Feasibility Study of the Senegal River Basin area entitled "Senegambia Project : Onchocerciasis Control in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, l,la1i, Senegal and Sierra Leone", had asked the Prograrrne to prepare a Plan of Operations for implementing activities in this area. It notes that the Expert Advisory Conrnittee (EAC) recormnended an alternative strategy, emphasizing the need to focus, in the first instance, on those areas where onchocerciasis was hyperendemic and on those rivers which were sources of reinvasion of the present OCP area (Document JPC3.3). The CSA endorses the need for onchocerciasis control in the Western extension area. However, following informal consultations, and bearing in mind the prevailing financial situation, the CSA reconrnends that activities be implemented in the area on a scale that can be managed by the Prograrmne and at a pace concomitant with the availability of funds, in order to obtain the basic data which have been identified as missing by the proposed plan of operations. -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (Pays Dogon)»

MINISTERE DE LA CULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI *********** Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi DIRECTION NATIONALE DU ********** PATRIMOINE CULTUREL ********** RAPPORT SUR L’ETAT DE CONSERVATION DU SITE «FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (Pays Dogon)» Janvier 2020 RAPPORT SUR L’ETAT ACTUEL DE CONSERVATION FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (PAYS DOGON) (MALI) (C/N 516) Introduction Le site « Falaises de Bandiagara » (Pays dogon) est inscrit sur la Liste du Patrimoine Mondial de l’UNESCO en 1989 pour ses paysages exceptionnels intégrant de belles architectures, et ses nombreuses pratiques et traditions culturelles encore vivaces. Ce Bien Mixte du Pays dogon a été inscrit au double titre des critères V et VII relatif à l’inscription des biens: V pour la valeur culturelle et VII pour la valeur naturelle. La gestion du site est assurée par une structure déconcentrée de proximité créée en 1993, relevant de la Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel (DNPC) du Département de la Culture. 1. Résumé analytique du rapport Le site « Falaises de Bandiagara » (Pays dogon) est soumis à une rude épreuve occasionnée par la crise sociopolitique et sécuritaire du Mali enclenchée depuis 2012. Cette crise a pris une ampleur particulière dans la Région de Mopti et sur ledit site marqué par des tensions et des conflits armés intercommunautaires entre les Dogons et les Peuls. Un des faits marquants de la crise au Pays dogon est l’attaque du village d’Ogossagou le 23 mars 2019, un village situé à environ 15 km de Bankass, qui a causé la mort de plus de 150 personnes et endommagé, voire détruit des biens mobiliers et immobiliers. -

Inventaire Des Aménagements Hydro-Agricoles Existants Et Du Potentiel Amenageable Au Pays Dogon

INVENTAIRE DES AMÉNAGEMENTS HYDRO-AGRICOLES EXISTANTS ET DU POTENTIEL AMENAGEABLE AU PAYS DOGON Rapport de mission et capitalisation d’expérienCe Financement : Projet d’Appui de l’Irrigation de Proximité (PAIP) Réalisation : cellule SIG DNGR/PASSIP avec la DRGR et les SLGR de la région de Mopti Bamako, avril 2015 Table des matières I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Méthodologie appliquée ................................................................................................................ 3 III. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans le cercle de Bandiagara .......... 4 1. Déroulement des activités dans le cercle de Bandiagara ................................................................................... 7 2. Bilan de l’inventaire du cercle de Bandiagara .................................................................................................... 9 IV. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans les cercles de Bankass et Koro 9 1. Déroulement des activités dans les deux cercles ............................................................................................... 9 2. Bilan de l’inventaire pour le cercle de Koro et Bankass ................................................................................... 11 Gelöscht: 10 V. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans le cercle de Douentza ............. 12 VI. Récapitulatif de l’inventaire -

R E GION S C E R C L E COMMUNES No. Total De La Population En 2015

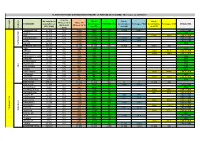

PLANIFICATION DES DISTRIBUTIONS PENDANT LA PERIODE DE SOUDURE - Mise à jour au 26/05/2015 - % du CH No. total de la Nb de Nb de Nb de Phases 3 à 5 Cibles CH COMMUNES population en bénéficiaires TONNAGE CSA bénéficiaires Tonnages PAM bénéficiaires Tonnages CICR MODALITES (Avril-Aout (Phases 3 à 5) 2015 (SAP) du CSA du PAM du CICR CERCLE REGIONS 2015) TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 12% 8 044 8 044 217 10 055 699,8 CSA + PAM ALAFIA 15 844 12% 1 901 1 901 51 CSA BER 23 273 12% 2 793 2 793 76 6 982 387,5 CSA + CICR BOUREM-INALY 14 239 12% 1 709 1 709 46 2 438 169,7 CSA + PAM LAFIA 9 514 12% 1 142 1 142 31 1 427 99,3 CSA + PAM SALAM 26 335 12% 3 160 3 160 85 CSA TOMBOUCTOU TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 18 748 18 749 506 13 920 969 6 982 388 DIRE 24 954 10% 2 495 2 495 67 CSA ARHAM 3 459 10% 346 346 9 1 660 92,1 CSA + CICR BINGA 6 276 10% 628 628 17 2 699 149,8 CSA + CICR BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 10% 1 050 1 050 28 CSA DANGHA 15 835 10% 1 584 1 584 43 CSA GARBAKOIRA 6 934 10% 693 693 19 CSA HAIBONGO 17 494 10% 1 749 1 749 47 CSA DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 10% 506 506 14 CSA KONDI 3 744 10% 374 374 10 CSA SAREYAMOU 20 794 10% 2 079 2 079 56 9 149 507,8 CSA + CICR TIENKOUR 8 009 10% 801 801 22 CSA TINDIRMA 7 948 10% 795 795 21 2 782 154,4 CSA + CICR TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 10% 356 356 10 CSA DIRE TOTAL 134 559 13 456 13 456 363 0 0 16 290 904 GOUNDAM 15 444 15% 2 317 9 002 243 3 907 271,9 CSA + PAM ALZOUNOUB 5 493 15% 824 3 202 87 CSA BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 15% 1 530 5 946 161 4 080 226,4 CSA + CICR ADARMALANE 1 172 15% 176 683 18 469 26,0 CSA + CICR DOUEKIRE 22 203 15% 3 330 -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

World Bank Document

69972 Options for Preparing a Sustainable Land Management (SLM) Program in Mali Consistent with TerrAfrica for World Bank Engagement at the Country Level Introduction Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Background and rationale: 1. One of the most environmentally vulnerable areas of the world is the drylands of sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and Southeast Africa. Mali, as with other dryland areas in this category, suffers from droughts approximately every 30 years. These droughts triple the number of people exposed to severe water scarcity at least once in every generation, leading to major food and health crisis. In general, dryland populations lag far behind the rest of the world in human well-being and development indicators. Similarly, the average infant mortality rate for dryland developing countries exceeds that for non-dryland countries by 23% or more. The human causes of degradation1 and desertification2 include direct factors such as land use (agricultural expansion in marginal areas, deforestation, overgrazing) and indirect factors (policy failures, population pressure, land tenure). The biophysical impacts of dessertification are regional and global climate change, impairment of carbon sequestation capacity, dust storms, siltation into rivers, downstream flooding, erosion gullies and dune formation. The social impacts are devestating- increasing poverty, decreased agricultural and silvicultural production and sometimes Public Disclosure Authorized malnutrition and/or death. 2. There are clear links between land degradation and poverty. Poverty is both a cause and an effect of land degradation. Poverty drives populations to exploit their environment unsustainably because of limited resources, poorly defined property rights and limited access to credit, which prevents them from investing resources into environmental management.