The State Nation's Housing 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality by Chad Stone, Danilo Trisi, Arloc Sherman, and Jennifer Beltrán

Updated January 13, 2020 A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality By Chad Stone, Danilo Trisi, Arloc Sherman, and Jennifer Beltrán The broad facts of income inequality over the past seven decades are easily summarized: • The years from the end of World War II into the 1970s were ones of substantial economic growth and broadly shared prosperity. o Incomes grew rapidly and at roughly the same rate up and down the income ladder, roughly doubling in inflation-adjusted terms between the late 1940s and early 1970s. o The gap between those high up the income ladder and those on the middle and lower rungs — while substantial — did not change much during this period. • Beginning in the 1970s, economic growth slowed and the income gap widened. o Income growth for households in the middle and lower parts of the distribution slowed sharply, while incomes at the top continued to grow strongly. o The concentration of income at the very top of the distribution rose to levels last seen nearly a century ago, during the “Roaring Twenties.” • Wealth — the value of a household’s property and financial assets, minus the value of its debts — is much more highly concentrated than income. The best survey data show that the share of wealth held by the top 1 percent rose from 30 percent in 1989 to 39 percent in 2016, while the share held by the bottom 90 percent fell from 33 percent to 23 percent. Data from a variety of sources contribute to this broad picture of strong growth and shared prosperity for the early postwar period, followed by slower growth and growing inequality since the 1970s. -

Supplem Ental Inform Ation

Supplemental Information Supplemental Summary of FY 2006 Appropriations Language Changes Summary of FY 2006 Appropriations Language technology modernization requirements; not to Changes exceed [$100,000] $150,000 for official reception and representation expenses; and not to exceed $258,000 Departmental Offices for unforeseen emergencies of a confidential nature, Salaries and Expenses to be allocated and expended under the direction of (Including Transfer of Funds) the Secretary of the Treasury and to be accounted For necessary expenses of the Departmental Offices for solely on his certificate: Provided further, That including operation and maintenance of the Treasury of the amount appropriated under this heading, Building and Annex; hire of passenger motor [$3,393,000] $5,173,000, to remain available until vehicles; maintenance, repairs, and improvements September 30, [2006] 2007, is for the Treasury-Wide of, and purchase of commercial insurance policies Financial Statement Audit Program, of which such for, real properties leased or owned overseas, amounts as may be necessary may be transferred to when necessary for the performance of official accounts of the Department’s offices and bureaus to business,[$157,559,000] $195,253,000, of which conduct audits: Provided further, That this transfer not to exceed [$7,274,000] $16,656,000 for authority shall be in addition to any other providedChanges Language Appropriations 2006 FY of Summary executive direction program activities; [not to exceed in this Act. (Transportation, Treasury, Independent -

Income, Expenditures, Poverty, and Wealth

Section 13 Income, Expenditures, Poverty, and Wealth This section presents data on gross periodically conducts the Survey of domestic product (GDP), gross national Consumer Finances, which presents finan- product (GNP), national and personal cial information on family assets and net income, saving and investment, money worth. The most recent survey is available income, poverty, and national and at <http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs personal wealth. The data on income and /oss/oss2/scfindex.html>. Detailed infor- expenditures measure two aspects of the mation on personal wealth is published U.S. economy. One aspect relates to the periodically by the Internal Revenue National Income and Product Accounts Service (IRS) in SOI Bulletin. (NIPA), a summation reflecting the entire complex of the nation’s economic income National income and product— and output and the interaction of its GDP is the total output of goods and major components; the other relates to services produced by labor and prop- the distribution of money income to erty located in the United States, valued families and individuals or consumer at market prices. GDP can be viewed in income. terms of the expenditure categories that comprise its major components: The primary source for data on GDP, GNP, personal consumption expenditures, national and personal income, gross gross private domestic investment, net saving and investment, and fixed assets exports of goods and services, and gov- and consumer durables is the Survey of ernment consumption expenditures and Current Business, published monthly by gross investment. The goods and services the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). included are largely those bought for final A comprehensive revision to the NIPA use (excluding illegal transactions) in the was released beginning in July 2009. -

IRS Statistics of Income, Census Current Population Survey, and BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey Eric L

A Comparison of Income Concepts: IRS Statistics of Income, Census Current Population Survey, and BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey Eric L. Henry and Charles D. Day, Internal Revenue Service everal Federal Government agencies produce tionnaire is administered at the household level, with statistics on individual and household income. information being collected for each person living in the SBecause of the differing purposes to which their household over age 15 [4]. data will be put, agencies use different definitions for income (income concepts), as well as different reporting BLS conducts the CE. It is the “basic source of data units, sample designs, collection modes, and process- for revising the items and weights in the market basket ing rules. Data users are faced with an array of choices, of consumer purchases to be priced for the Consumer often without much help to sort out which data series Price Index.” It consists of two components, a quarterly best meets their needs or much guidance to reconcile interview survey and a weekly diary survey. The CE results based on different sources of data. targets the entire noninstitutionalized population of the United States [5]. In order to help users, a number of papers have been written comparing the Census Bureau’s Current SOI Individual taxpayer data are an administrative Population Survey (CPS) Money Income and Survey of data set. The data are collected from a sample of Forms Income and Program Participation concepts, the Bureau 1040 filed by individual taxpayers [6]. The target popula- of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey tion is all individuals required to file a tax return. -

Department of the Treasury

DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY DEPARTMENTAL OFFICES Change in obligated balance: Unpaid obligations: Federal Funds 3000 Unpaid obligations, brought forward, Oct 1 .......................... 89 91 70 3010 New obligations, unexpired accounts .................................... 327 331 214 SALARIES AND EXPENSES 3011 Obligations ("upward adjustments"), expired accounts ........ 7 ................. ................. For necessary expenses of the Departmental Offices including operation and 3020 Outlays (gross) ...................................................................... –318 –352 –256 3040 Recoveries of prior year unpaid obligations, unexpired ......... –1 ................. ................. maintenance of the Treasury Building and Freedman's Bank Building; hire of pas- 3041 Recoveries of prior year unpaid obligations, expired ............. –13 ................. ................. senger motor vehicles; maintenance, repairs, and improvements of, and purchase of commercial insurance policies for, real properties leased or owned overseas, 3050 Unpaid obligations, end of year ................................................. 91 70 28 Uncollected payments: when necessary for the performance of official business; executive direction program 3060 Uncollected pymts, Fed sources, brought forward, Oct 1 ........ –35 –32 –32 activities; international affairs and economic policy activities; domestic finance and 3070 Change in uncollected pymts, Fed sources, unexpired .......... –21 ................. ................. tax policy activities, including -

A Guide to Describing the Income Distribution

A Guide to Describing the Income Distribution Sarah A. Donovan Analyst in Labor Policy February 5, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43897 A Guide to Describing the Income Distribution Summary The distribution of income in the United States features heavily in congressional discussions about the middle class, program funding and effectiveness, new and existing target groups, government tax revenue, and social mobility, among other topics. Recently, the level and distribution of U.S. income have also been raised in the context of broader macroeconomic issues, such as economic growth. Accordingly, Congress has sought information on the absolute and relative experience of U.S. households, the range of incomes, and their dispersion. Describing the income distribution involves several important choices about the definition of income and the level at which income data are examined. Income can be constructed narrowly (e.g., earnings only) or broadly (e.g., as the sum of earnings, capital gains, government transfers, and other sources); it can be presented in pre-tax status or reflect taxes paid and tax credits received. Income can be presented at the individual level or represent pooled resources among households, families, or tax units. These choices about how to define income affect the magnitude of income indicators and the shape and range of the U.S. income distribution. For this reason, disagreement over the interpretation of income levels and trends frequently centers on how income is defined. This report is a guide to various measures, indicators, and graphics commonly used to describe the U.S. income distribution. It examines the complexities of income measurement, outlines important definitional and data considerations to bear in mind when using and interpreting income statistics, and reviews descriptive statistics commonly used in analysis. -

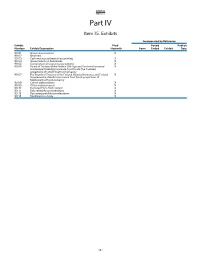

PART IV Item 15 Part IV Item 15

PART IV Item 15 Part IV Item 15. Exhibits Incorporated by Reference Exhibit Filed Period Publish Number Exhibit Description Herewith Form Ended Exhibit Date 99.01 Government sources X 99.02 Reserved 99.03 Cash and accrual bases of accounting X 99.04 Government-run businesses X 99.05 Composition of segment expenditures X 99.06 Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance X and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds (the Trustees) projections of OASDI trust fund solvency 99.07 The Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal X Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds projections of Medicare trust funds solvency 99.08 Cohort table creation X 99.09 Other similar projects X 99.10 Excluded Form 10-K content X 99.11 Data reliability considerations X 99.12 Data comparability considerations X 99.13 Modification of data X 187 Exhibit 99.01 Data sourced from our website The majority of the data included in this report can be found on our website with accompanying citations. The original sources for that data as of the time of the publishing of this report are: Agency for International Department of Homeland Department of State National Science Foundation Development Security National Center for Science and Customs and Border Protection Department of Transportation Engineering Statistics Consumer Financial Protection Federal Emergency Management Bureau of Transportation Statistics Bureau Agency Federal Highway Administration Nuclear Regulatory Transportation Security National Highway Traffic Safety Commission -

Maintaining the Strength of American Capitalism

MAINTAINING THE STRENGTH OF AMERICAN CAPITALISM Foreword by HENRY M. PAULSON, JR. and ERSKINE BOWLES Edited by MELISSA S. KEARNEY and AMY GANZ Copyright © 2019 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute 2300 N Street, N.W. Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 Published in the United States of America in 2019 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Wye Publication Number: 19/011 MAINTAINING THE STRENGTH OF AMERICAN CAPITALISM Foreword by HENRY M. PAULSON JR. KEARNE and ERSKINE BOWLES Edited by MELISSA S. KEARNEY Y / and AMY GANZ GANZ Foreword by HENRY M. PAULSON, JR. and ERSKINE BOWLES Edited by MELISSA S. KEARNEY and AMY GANZ DECEMBER 2019 Acknowledgements We thank the many individuals who were instrumental in the production of this volume. First, the members of the Economic Strategy Group, whose thoughtful suggestions and discussion motivated the subject of this book. We are grateful to the authors of this volume, whose contributions advanced our understanding of complex topics and challenged us to think more deeply about potential policy responses. We are grateful for the individuals and organizations whose generous support makes possible the work of the Economic Strategy Group. We are grateful to the leadership of The Aspen Institute for its continued support of the Economic Strategy Group’s mission. We thank the staff who invested countless hours in producing this volume: Andy Morimoto and Kelley Folino for their helpful feedback; Dwyer Gunn and Kate Wheeling for excellent proofreading and editing assistance; Emily Vincent and Anne Hawkins for superb project management; Daniel Schiff for insightful research assistance; and Krista Martin, Sogand Sepassi, and Steven Johnson for their thorough editing and layout work. -

F4B Manage Federal Debt Effectively and Efficiently

EASU TR RY � � REASURY C Y T O www.treas.gov C Treasury On-line M N P O E T F R R F N O R I O U C L I L C E S E I E Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) www.ttb.gov R H O V O F T F R E T H P R I F T S U Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) www.moneyfactory.gov Bureau of the Public Debt (BPD) www.publicdebt.treas.gov P U T B L B I C D E CIAL C AN RI N M I E F S Community Development Financial Institutions (CFDI) www.cdfifund.gov E N F O K R R C O EM TW Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) www.fincen.gov ENT NE Financial Management Service (FMS) www.fms.treas.gov EASUR TR Y Internal Revenue Service (IRS) www.irs.gov I N T F E E I N R C E N I C A A I V L V N R R R E C E S E U. S. Mint (Mint) www.usmint.gov V E I ENU S A L T M N A E NAGEM Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) www.occ.treas.gov Office of the Comptroller of the Currency United States Mint Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) www.ots.treas.gov Bureau of Engraving and Printing Bureau of the Public Debt Financial Crimes Enforcement Network Office of Thrift Supervision Financial Management Service Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Internal Revenue Service Table of Contents Treasury Seals .......................................................................................................................Front Back Cover Message from the Secretary Message from the Acting Assistant Secretary for Management and the Acting Chief Financial Officer Part I - Management's Discussion and Analysis Executive Summary Introduction............................................................................................................................................ -

Integration of Micro and Macro Data on Consumer Income and Expenditures

Integration of Micro and Macro Data on Consumer Income and Expenditures March 22, 2013 Clinton P. McCully Bureau of Economic Analysis Macro estimates of household income and expenditures from the Bureau of Economic Analysis measure aggregate and per capita averages, but provide no information on the distribution of income, which is important in the measurement of economic well-being. Micro estimates of household income and expenditures have information on income distribution and other household breakdowns, but are confined to the measurement of cash income and direct household expenditures, and suffer from problems of nonreporting, underreporting, and underrepresentation of high-income households. Integrated estimates of household income and expenditures provide estimates of income distribution consistent with the more accurate and broadly-defined macro values, which include third-party payments, such as those by employers and government for health care, and account for the effects of income taxes. Integrated estimates of household disposable income show a lesser degree of income inequality than do micro estimates from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, largely because of the inclusion of in-kind government social benefits, primarily for health care, that disproportionately benefit lower-income households, and of the exclusion from income of personal income taxes, which are paid disproportionately by high-income households. Changes between 2006 and 2010 show a small narrowing in income discrepancies, reflecting declines in self-employment and property income of the top quintile and increases in government social benefits and lower taxes for the lowest quintile. Note: National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) data cited in this report reflect published estimates prior to the revised estimates for 2009 and 2010 released in July 2012. -

Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States

For use at 12:00 p.m., eastern time Friday June 9, 2000 FEDERAL RESERVE statistical release Z.1 Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States Flows and Outstandings First Quarter 2000 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington DC 20551 Flow of Funds Summary Statistics First Quarter 2000 Growth of domestic nonfinancial debt slowed to debt, at a 1-1/4 percent annual rate of increase, remained a 5-1/2 percent annual rate in the first quarter of 2000, subdued. owing to a resumption of large paydowns in federal debt after a pause in the fourth quarter. Since its peak The level of domestic nonfinancial debt in early 1998, federal debt held by the public has outstanding was $17.7 trillion at the end of the first dropped about 4-1/2 percent, or $177 billion. quarter. Debt of nonfederal sectors was $14.1 trillion, and federal debt was $3.6 trillion. Meanwhile, household and business borrowing remained brisk. In the first quarter, household debt rose Figures for the growth and level of debt are found at a 7-3/4 percent pace, somewhat slower than in recent in tables D.1 through D.3. Tables that show financial quarters as home mortgage borrowing decreased a bit. flows, amounts outstanding, and selected sector Business debt expanded at a 10-1/2 percent annual rate balance sheets are included in the remaining pages of in the first quarter, as firms tapped all major sources of this release. credit in volume. Growth of state and local government Growth of Domestic Nonfinancial Debt1 Percentage changes; quarterly data are seasonally adjusted annual rates Nonfederal Total Federal Total Households Business State and local govts. -

Federal Government Finances and Employment

Section 10 Federal Government Finances and Employment This section presents statistics relating to activities—including the Federal Financing the financial structure and the civilian em- Bank, the Postal Service, the Synthetic Fu- ployment of the Federal Government. The els Corporation, and the lending activities fiscal data cover taxes, other receipts, out- of the Rural Electrification Administration. lays, and debt. The principal sources of fis- The Balanced Budget and Emergency Defi- cal data are The Budget of the United States cit Control Act of 1985 (P.L.99-177) re- Government and related documents, pub- pealed the off-budget status of these enti- lished annually by the Office of Manage- ties and placed social security (Federal old- ment and Budget (OMB), and the Depart- age and survivors insurance and the Fed- ment of the Treasury’s United States Gov- eral disability insurance trust funds) off- ernment Annual Report and its Appendix. budget. Though social security is now off- Detailed data on tax returns and collec- budget and, by law, excluded from cover- tions are published annually by the Internal age of the congressional budget resolu- Revenue Service. The personnel data relate tions, it continues to be a Federal program. to staffing and payrolls. They are pub- Receipts arising from the Government’s lished by the Office of Personnel Manage- sovereign powers are reported as govern- ment and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. mental receipts; all other receipts, i.e., The primary source for data on public from business-type or market-oriented ac- lands is Public Land Statistics, published tivities, are offset against outlays.