Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan - Controversial Origins, Design Defects, and Free Speech Implications Osama Siddique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the Legislature in Upholding the Rule of Law in Bangladesh Md

The Role of the Legislature in Upholding the Rule of Law in Bangladesh Md. Mostafijur Rahman 1 Abstract : In the contemporary global politics the rule of law is considered as the pre-requisite for better democracy, socio-economic development and good govern- ance. It is also essential in the creation and advancement of citizens’ rights of a civilized society and being considered for solving many problems in the developing country. The foremost role of the legislature-as second branch of government to recognise the rights of citizens and to assure the rule of law prevails. In order to achieve this goal the legislature among the pillars of a state should be constructive, effective, functional and meaningful. Although the rule of law is the basic feature of the constitution of Bangladesh the current state of the rule of law is a frustration because, almost in all cases, it does not favour the rights of the common people. Under the circumstances, the existence of the rule of law without an effective parlia- ment is conceivable. The main purpose of this study is to examine to what extent the parliament plays a role in upholding the rule of law in Bangladesh and conclude with pragmatic way forward accordingly. Keywords: Rule of law, principles of law, citizens’ rights, legislature, electoral procedure, legislative process. Introduction The ‘rule of law’ is opposed to ‘rule of man’. The term ‘rule of law’ is derived from the French phrase la Principe de legalite (the princi- ple of legality) which refers to a government based on principles of law and not of men. -

Men's Sexual Health in Bangladesh

Masculinities, generations and health: Men's sexual health in Bangladesh Md Kamrul Hasan A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy r .. s ( . ' :~ - ,\ l ! S I R 1\ l I ,,\ Centre for Social Research in Health Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences UNSW Australia • February 2017 • .. PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hasan First name: Md Kamrul Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD Faculty: Faculty of Arts and Social School: Centre for Social Research in Health Sciences Title: Masculinities, generations and health: Men's sexual health in Bangladesh Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Together, men, masculinities and health comprise an emerging area of research, activism and policy debate. International research on men's health demonstrates how men's enactment of masculinity may be linked to their sexual health risk. However, little research to date has explored men's enactment of different forms of masculinity and men's sexual health from a social generational perspective. To address this gap, insights from Mannheim's work on social generations, Connel�s theory of masculinity, Butler's theory of gender performativity, and Alldred and Fox's work on the sexuality assemblage, were utilised to offer a better understanding of the implications of masculinities for men's sexual health. A multi-site cross-sectional qualitative study was conducted in three cities in Bangladesh. Semi-structured interviews were used to capture narratives from 34 men representing three contrasting social generations: an older social generation (growing up pre-1971), a middle social generation (growing up in the 1980s and 1990s), and a younger social generation (growing up post-2010). -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

70+6'& 0#6+105 %4% %QPXGPVKQPQPVJG Distr. 4KIJVUQHVJG%JKN GENERAL CRC/C/65/Add.22 14 March 2003 Original: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Second periodic reports of States parties due in 1997 BANGLADESH* [12 June 2001] * For the initial report submitted by the Government of Bangladesh, see CRC/C/3/Add.38 and 49; for its consideration by the Committee, see documents CRC/C/SR.380-382 and CRC/C/15/Add.74. GE.03-40776 (E) 120503 CRC/C/65/Add.22 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. BACKGROUND ......................................................................... 1 - 5 3 II. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 6 - 16 4 A. Land and people .................................................................. 7 - 10 4 B. General legal framework .................................................... 11 - 16 5 III. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION ........................ 17 - 408 6 A. General measures of implementation ................................. 17 - 44 6 B. Definition of the child ......................................................... 45 - 47 13 C. General principles ............................................................... 48 - 68 14 D. Civil rights and freedoms ................................................... 69 - 112 18 E. Family environment and alternative care ........................... 113 - 152 25 F. Basic health and welfare .................................................... -

Fezana Agm 2013 Report

FEZANA 26th AGM REPORT BOOK INDEX 26th ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AGENDA MINUTES OF 25th AGM HELD IN NEW YORK (AUGUST 2012) FINANCIAL REPORTS Minutes of conference call to discuss Financial Statements ‐‐ April 6, 2013 Treasurer's Comments Snapshot Summary FEZANA Financial Statements ‐ 2012 EXECUTIVE REPORTS REPORT BY PRESIDENT REPORT BY VICE‐PRESIDENT REPORT BY SECRETARY COMMITTEE REPORTS Academic Scholarship Committee Education, Scholarship and Conference Committee Excellence in Sports Scholarship FEZANA Information Research System (FIRES) Funds and Finance Committee Interfaith Activities Committee Performing and Creative Arts Scholarship Publications ‐ Information Receiving and Dissemination Committee Publications: FEZANA Journal Publications: Accounts for Legacy; Connections; Flyers 2013 Public Relations Committee Research and Preservation Committee Small Groups Committee Unity and Welfare Committee Zoroastrian Sports Committee (ZSC) Zoroastrian Youth of North America (ZYNA) Zoroastrian Youth Without Borders (ZYWB) Z‐TEM (Zarathushti Treasures for Exhibits and Museums) OTHER REPORTS Demographics Infrastructure Development in North America Return to Roots Strategic Plan ‐ Second 10 Year Plan 2011‐2021 Zoroastrians Stepping Forward (ZSF) Welfare Activities with WZO Trust, 2012 FEZANA 26TH AGM REPORT BOOK PAGE 1 FEZANA 26TH AGM REPORT BOOK PAGE 2 FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA http://www.fezana.org Representing 26 Zoroastrian Associations and 12 Small Groups in the USA and Canada TWENTY SIXTH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING (AGM) OF FEZANA MAY 3RD TO 5TH, 2013 Host: Zoroastrian Association of Northern Texas Location: Hyatt Place Dallas/Grapevine 2220 Grapevine Mills Circle Grapevine, TX 76051 (972) 691-1199 Notes: 1. Member Association and Associate Member (Small Group) Presidents and/or their Reps to participate in the deliberations. Observers can comment and/or make suggestions when acknowledged by the Chair. -

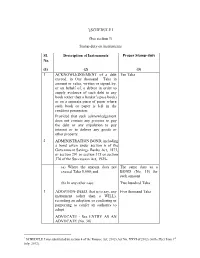

[SCHEDULE I (See Section 3) Stamp Duty on Instruments Sl. No. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-Duty (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWL

1[SCHEDULE I (See section 3) Stamp duty on instruments Sl. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-duty No. (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of a debt Ten Taka exceed, in One thousand Taka in amount or value, written or signed by, or on behalf of, a debtor in order to supply evidence of such debt in any book (other than a banker’s pass book) or on a separate piece of paper where such book or paper is left in the creditors possession: Provided that such acknowledgement does not contain any promise to pay the debt or any stipulation to pay interest or to deliver any goods or other property. 2 ADMINISTRATION BOND, including a bond given under section 6 of the Government Savings Banks Act, 1873, or section 291 or section 375 or section 376 of the Succession Act, 1925- (a) Where the amount does not The same duty as a exceed Taka 5,000; and BOND (No. 15) for such amount (b) In any other case. Two hundred Taka 3 ADOPTION-DEED, that is to say, any Five thousand Taka instrument (other than a WILL), recording an adoption, or conferring or purporting to confer an authority to adopt. ADVOCATE - See ENTRY AS AN ADVOCATE (No. 30) 1 SCHEDULE I was substituted by section 4 of the Finance Act, 2012 (Act No. XXVI of 2012) (with effect from 1st July, 2012). 4 AFFIDAVIT, including an affirmation Two hundred Taka or declaration in the case of persons by law allowed to affirm or declare instead of swearing. EXEMPTIONS Affidavit or declaration in writing when made- (a) As a condition of enlistment under the Army Act, 1952; (b) For the immediate purpose of being field or used in any court or before the officer of any court; or (c) For the sole purpose of enabling any person to receive any pension or charitable allowance. -

Death-Penalty-Pakistan

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty . -

THE MINORITY SAGA a Christian, Human Rights Perspective

THE MINORITY SAGA A Christian, Human Rights Perspective Yousuf Jalal Gill Publisher UMEED ACADEMY Umeed Partnership Pakistan (UPP) 1 Book: THE MINORITY SAGA A Christian, Human Rights Perspective Author: Yousuf Jalal Gill Publisher: UMEED ACADEMY Umeed Partnership Pakistan (UPP). House # 198/199, Block J-3, M.A. Johar Town, Lahore E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Tel 0092 42 35957302, Cell. 0092 300 9444482 Website: uppakistan.org, umeedpartnership.org.uk Printer: Zafarsons Printers, Lahore Edition: First Year: 2016 Print 1000 Price: Rs.200 UMEED ACADEMY Umeed Academy is the publishing arm of Umeed Partnership Pakistan (UPP) that is involved in developing disadvantaged communities through education and training. Umeed Academy publishes, in particular, research works on downtrodden, women and minorities and helps disseminate people-oriented publications so as to facilitate transformation of society through sustainable social change. The publications of Umeed Academy reflect views of the researchers and writers and not necessarily that of the UPP. 2 Dedicated to: Dr. John Perkins A consistent and fervent supporter of UPP in its endeavors to serve the most disadvantaged communities in Pakistan. 3 “The harvest is past, the summer is ended, and we are not saved.” -Jeremiah 8:20 4 “The test of courage comes when we are in the minority; the test of tolerance comes when we are in the majority.” -Ralph W. Sockman (American Writer) 5 6 About the Author The formative years of Yousuf Jalal Gill (b.1957) were spent with the Oblate Missionaries whom Pope Pius XI (1857 – 1939) referred to as the “Specialists in the most difficult missions…” Moreover, his youthful days witnessed an era of political upheaval after the dismemberment of erstwhile East Pakistan in 1971. -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

Conflict Between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study

Article Conflict between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study Amit Singh Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Colégio de S. Jerónimo Apartado 3087, 3000-995 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] Received: 24 March 2018; Accepted: 27 June 2018; Published: 29 June 2018 Abstract: The tussle between freedom of expression and religious intolerance is intensely manifested in Indian society where the State, through censoring of books, movies and other forms of critical expression, victimizes writers, film directors, and academics in order to appease Hindu religious-nationalist and Muslim fundamentalist groups. Against this background, this study explores some of the perceptions of Hindu and Muslim graduate students on the conflict between freedom of expression and religious intolerance in India. Conceptually, the author approaches the tussle between freedom of expression and religion by applying a contextual approach of secular- multiculturalism. This study applies qualitative research methods; specifically in-depth interviews, desk research, and narrative analysis. The findings of this study help demonstrate how to manage conflict between freedom of expression and religion in Indian society, while exploring concepts of Western secularism and the need to contextualize the right to freedom of expression. Keywords: freedom of expression; Hindu-Muslim; religious-intolerance; secularism; India 1. Background Ancient India is known for its skepticism towards religion and its toleration to opposing views (Sen 2005; Upadhyaya 2009), However, the alarming rise of Hindu religious nationalism and Islamic fundamentalism, and consequently, increasing conflict between freedom of expression and religion, have been well noted by both academic (Thapar 2015) and public intellectuals (Sorabjee 2018; Dhavan 2008). -

ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2015), Volume 3, Issue 8, 837- 845

ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2015), Volume 3, Issue 8, 837- 845 Journal homepage: http://www.journalijar.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCED RESEARCH RESEARCH ARTICLE ROLE OF ATTORNEY IN THE DEFAMATION OF RELIGION CRIME PROSECUTION AND RELATED TO OBJECTIVE OF SENTENCING Agung Dhedy Dwi Handes1 & Zulkifli Aspan2 1.Attorney General of the Republic of Indonesia 2. Department of Law, Hasanuddin University. Manuscript Info Abstract Manuscript History: This study aims to determine the role and constraints of the Prosecutor in the prosecution of the crime of defamation of religion is connected with the Received: 15 June 2015 Final Accepted: 18 July 2015 purpose of punishment. This study uses normative research and socio- Published Online: August 2015 juridical. The results showed how the relationship prosecution procedure and substance of the prosecution so that the role of the prosecution of the crime Key words: of defamation of religions can work well within the framework of law enforcement and the attainment of the objectives of punishment for the The prosecutor, Prosecution, perpetrators of the crime of blasphemy. Religion, Punishment *Corresponding Author Agung Dhedy Dwi Copy Right, IJAR, 2015,. All rights reserved Handes INTRODUCTION Freedom of religion is one of the human rights of the most fundamental (basic) and fundamental to every human being. The right to freedom of religion has been agreed by the world community as an inherent individual rights directly, which must be respected, upheld and protected by the state, the government, and everyone for the respect and protection of human dignity. This can be seen in the Constitutional Court Decision No. -

“Hate Spin”: the Limits of Law in Managing Religious Incitement and Offense

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 2955–2972 1932–8036/20160005 Regulating “Hate Spin”: The Limits of Law in Managing Religious Incitement and Offense CHERIAN GEORGE1 Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong As democracies try to manage the risks arising from religious vilification, questions are being raised about free speech and its limits. This article clarifies key issues in that debate. It centers on the phenomenon of “hate spin”—the giving or taking of offense as a political strategy. Any policy response must try to distinguish between incitement to actual harms and expression that becomes the object of manufactured indignation. An analysis of the use of hate spin by right-wing groups in India and the United States demonstrates that laws against incitement, while necessary, are insufficient for dealing with highly organized hate campaigns. As for laws against offense, these are counterproductive, because they tend to empower the most intolerant sections of society. Keywords: hate speech, incitement, offense, freedom of expression, censorship, India, United States, First Amendment How to regulate religious offense has become one of the most contentious questions concerning freedom of expression. The 2015 murder of Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in revenge for their satirical depictions of the Prophet Mohammed was just one of several traumatic incidents that have prompted democracies to ponder once again the tension between free speech and respect for religion. If only to protect people from violent retribution, some commentators wonder whether the time has come to set stricter limits on the right to offend. For example, the European Council on Tolerance and Reconciliation (2015), chaired by former British prime minister Tony Blair, has proposed laws for combating intolerance that would temper liberal democracies’ position on free speech. -

Defining Shariʿa the Politics of Islamic Judicial Review by Shoaib

Defining Shariʿa The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review By Shoaib A. Ghias A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Malcolm M. Feeley, Chair Professor Martin M. Shapiro Professor Asad Q. Ahmed Summer 2015 Defining Shariʿa The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review © 2015 By Shoaib A. Ghias Abstract Defining Shariʿa: The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review by Shoaib A. Ghias Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Malcolm M. Feeley, Chair Since the Islamic resurgence of the 1970s, many Muslim postcolonial countries have established and empowered constitutional courts to declare laws conflicting with shariʿa as unconstitutional. The central question explored in this dissertation is whether and to what extent constitutional doctrine developed in shariʿa review is contingent on the ruling regime or represents lasting trends in interpretations of shariʿa. Using the case of Pakistan, this dissertation contends that the long-term discursive trends in shariʿa are determined in the religio-political space and only reflected in state law through the interaction of shariʿa politics, regime politics, and judicial politics. The research is based on materials gathered during fieldwork in Pakistan and datasets of Federal Shariat Court and Supreme Court cases and judges. In particular, the dissertation offers a political-institutional framework to study shariʿa review in a British postcolonial court system through exploring the role of professional and scholar judges, the discretion of the chief justice, the system of judicial appointments and tenure, and the political structure of appeal that combine to make courts agents of the political regime.