Acr–Sar Practice Parameter for the Performance of Adult Cystography and Urethrography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contrast‐Enhanced Ultrasound Bibliography General Principles 1

Contrast‐enhanced Ultrasound Bibliography General Principles 1.Claudon M et al. Guidlines and Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Contrast Ultrasound (CEUS)‐Update 2008 Ultraschall in Med 2008;29:28‐44 2.Cosgrove. D. Editorial. Eur Radiol Suppl (2004).14[Suppl 8]:1‐3 3.Burns PN, Wilson,S. Microbubble Contrast for Radiological Imaging:1 Principles. Ultrasound Quarterly 2006;22:5‐11 4.Wilson S et al. Contrast‐enhanced Ultrasound: What is the Evidence and What Are the Obstacles? AJR. 2009;193:55‐60 Safety 1.ter Haar GR. Ultrasonic Contrast Agents: Safety Considerations Reviewed. Eur J Radiol 2002;41:217‐221 2. Main MI. Ultrasound Contrast Agent Safety. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2009:2:1057‐ 1059 3. Pisaglia F et al. SonoVue in Abdominal applications: Retrospective Analysis of 23188 Investigations. Ultrasound in Med and Biol.2006;32:1369‐1375 4. Hynynen K et al. The Threshold for Brain Damage in Rabbits Induced By Bursts of Ultrasound in the Presence of an Ultrasound Contrast Agent (Optison). Ultrasound in Med and Biol;29:473‐481 Voiding Urosonography 1.Darge K. et al. Reflux in Young Patients: Comparison of Voiding US of the Bladder and Retrovesical Space with Echo Enhancement versus Voiding Cystourethrography for Diagnosis. Radiology 1999;210:201‐207 2.Radmayr C et al. Contrast Enhanced Reflux Sonography in Children: A Comparison to Standard Radiological Imaging J Urol 2002;167:1428‐30 Liver Lesion Characterization 1.Bolondi L et al. New Perspectives for the Use of Contrast‐Enhanced Liver Ultrasound in Clinical Practice. Digestive and Liver Disease 2007;39:187‐195 2.Berry J, Sidu, P. -

Nuclear Medicine for Medical Students and Junior Doctors

NUCLEAR MEDICINE FOR MEDICAL STUDENTS AND JUNIOR DOCTORS Dr JOHN W FRANK M.Sc, FRCP, FRCR, FBIR PAST PRESIDENT, BRITISH NUCLEAR MEDICINE SOCIETY DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR MEDICINE, 1ST MEDICAL FACULTY, CHARLES UNIVERSITY, PRAGUE 2009 [1] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would very much like to thank Prof Martin Šámal, Head of Department, for proposing this project, and the following colleagues for generously providing images and illustrations. Dr Sally Barrington, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, St Thomas’s Hospital, London Professor Otakar Bělohlávek, PET Centre, Na Homolce Hospital, Prague Dr Gary Cook, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, Royal Marsden Hospital, London Professor Greg Daniel, formerly at Dept of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, currently at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), Past President, American College of Veterinary Radiology Dr Andrew Hilson, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, Royal Free Hospital, London, Past President, British Nuclear Medicine Society Dr Iva Kantorová, PET Centre, Na Homolce Hospital, Prague Dr Paul Kemp, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, Southampton University Hospital Dr Jozef Kubinyi, Institute of Nuclear Medicine, 1st Medical Faculty, Charles University Dr Tom Nunan, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, St Thomas’s Hospital, London Dr Kathelijne Peremans, Dept of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ghent Dr Teresa Szyszko, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, St Thomas’s Hospital, London Ms Wendy Wallis, Dept of Nuclear Medicine, Charing Cross Hospital, London Copyright notice The complete text and illustrations are copyright to the author, and this will be strictly enforced. Students, both undergraduate and postgraduate, may print one copy only for personal use. Any quotations from the text must be fully acknowledged. It is forbidden to incorporate any of the illustrations or diagrams into any other work, whether printed, electronic or for oral presentation. -

Nuclear Pharmacy Quick Sample

12614-01_CH01-rev3.qxd 10/25/11 10:56 AM Page 1 CHAPTER 1 Radioisotopes Distribution for Not 1 12614-01_CH01-rev3.qxd 10/25/1110:56AMPage2 2 N TABLE 1-1 Radiopharmaceuticals Used in Nuclear Medicine UCLEAR Chemical Form and Typical Dosage P Distribution a b HARMACY Radionuclide Dosage Form Use (Adult ) Route Carbon C 11 Carbon monoxide Cardiac: Blood volume measurement 60–100 mCi Inhalation Carbon C 11 Flumazenil injection Brain: Benzodiazepine receptor imaging 20–30 mCi IV Q UICK Carbon C 11 Methionine injection Neoplastic disease evaluation in brain 10–20 mCi IV R Carbon C 11 forRaclopride injection Brain: Dopamine D2 receptor imaging 10–15 mCi IV EFERENCE Carbon C 11 Sodium acetate injection Cardiac: Marker of oxidative metabolism 12–40 mCi IV Carbon C 14 Urea Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection 1 µCi PO Chromium Cr 51 Sodium chromate injection Labeling red blood cells (RBCs) for mea- 10–80 µCi IV suring RBC volume, survival, and splenic sequestration Cobalt Co 57 Cyanocobalamin capsules Diagnosis of pernicious anemia and 0.5 µCi PO Not defects of intestinal absorption Fluorine F 18 Fludeoxyglucose injection Glucose utilization in brain, cardiac, and 10–15 mCi IV neoplastic disease Fluorine F 18 Fluorodopa injection Dopamine neuronal decarboxylase activity 4–6 mCi IV in brain Fluorine F 18 Sodium fluoride injection Bone imaging 10 mCi IV Gallium Ga 67 Gallium citrate injection Hodgkin’s disease, lymphoma 8–10 mCi IV Acute inflammatory lesions 5 mCi IV Indium In 111 Capromab pendetide Metastatic imaging in patients with biopsy- -

ACR–SPR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Voiding

The American College of Radiology, with more than 30,000 members, is the principal organization of radiologists, radiation oncologists, and clinical medical physicists in the United States. The College is a nonprofit professional society whose primary purposes are to advance the science of radiology, improve radiologic services to the patient, study the socioeconomic aspects of the practice of radiology, and encourage continuing education for radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and persons practicing in allied professional fields. The American College of Radiology will periodically define new practice parameters and technical standards for radiologic practice to help advance the science of radiology and to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the United States. Existing practice parameters and technical standards will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated. Each practice parameter and technical standard, representing a policy statement by the College, has undergone a thorough consensus process in which it has been subjected to extensive review and approval. The practice parameters and technical standards recognize that the safe and effective use of diagnostic and therapeutic radiology requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in each document. Reproduction or modification of the published practice parameter and technical standard by those entities not providing these services is not authorized. Revised 2019 (Resolution 10)* ACR–SPR PRACTICE PARAMETER FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF FLUOROSCOPIC AND SONOGRAPHIC VOIDING CYSTOURETHROGRAPHY IN CHILDREN PREAMBLE This document is an educational tool designed to assist practitioners in providing appropriate radiologic care for patients. Practice Parameters and Technical Standards are not inflexible rules or requirements of practice and are not intended, nor should they be used, to establish a legal standard of care1. -

500 Pyelograms Done After Angiocardiography. the Urinary Tract

9 Section ofRadiology 419 often transitory, it can readily be reproduced by In 200 consecutive pyelograms, analysed both instructing the child to hold back urine and we by congenital heart lesion and urinary tract now believe that this is a common variation of the abnormality, the incidence of abnormal pyelo- normal. It is probably due to distension of the grams was 13 %. The range ofabnormality in both thin-walled proximal urethra, the less distensible is very wide. Pyelogram abnormalities in this bladder neck and distal urethra forming two series and subsequently have included failure of relatively narrow segments. maturation of kidney with pelvis lying intra- renally, solitary kidney, chronic pyelonephritic A 'corkscrew urethra' has been seen in 4 boys kidney, large kidneys, renal rotation, hydro- in this series. It may be associated with reflux. nephrosis, absence of renal pelves, duplication of Cystoscopy and urethroscopy has been normal kidney and ureter (one having a pyelonephritic and in one patient recordings of pressure and lower segment and evidence of vesicoureteric flow were also normal. We can only assume that reflux - Williams 1962), hydroureter and spinal this appearance is produced by redundant folds defects with neurogenic bladder. Factors affecting of mucosa; certainly there has been no evidence cardiac development may affect organogenesis in of obstruction in any of our cases. the urinary tract. The rubella virus was the defined factor in a patient, aged 4 months, with patent Summary ductus arteriosus, pulmonary hypertension and Micturating cystograms carried out in 232 pneumonitis and a miniature left kidney (autopsy children presenting with urinary infection, but proof). -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

Use of Ultrasound As an Alternative to Fluoroscopy

Use of Ultrasound as an Alternative to Fluoroscopy Rahul Sheth, MD Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA PART 1. INTERVENTIONAL PROCEDURES Fluoroscopy has significantly contributed to the advent and proliferation of image-guided interventions across the gamut of clinical medicine. While these procedures allow for the execution of often complex internal manipulations through a small skin nick rather than a surgical incision, they are not without risk, including the risks of ionizing radiation [1]. In these procedures, fluoroscopy simply serves as an image guidance tool, and as such, alternative imaging modalities that do not rely on ionizing radiation can and should be considered. For example, as a real-time, high resolution imaging modality, ultrasound shares many characteristics with fluoroscopy. However, due to its lack of reliance on ionizing radiation, ultrasound is often the imaging tool of choice for a number of image-guided interventions for which fluoroscopy may also be considered, particularly in the pediatric population. The following examples illustrate specific indications in which ultrasound is preferred over fluoroscopy for interventional procedures. Ultrasound Instead Of Fluoroscopy For Musculoskeletal Procedures Ultrasound is ideally suited for image guided interventions upon the musculoskeletal system [2], as the depth of penetration required for these procedures is typically within several centimeters. A wide array of musculoskeletal interventions can be performed with ultrasound guidance, including arthrocentesis [3,4], joint and soft tissue steroid/anesthetic injections [5,6,7], and aspirations [8,9]. Moreover, while fluoroscopy is the most common imaging modality used for cervical nerve blocks and facet injections, there has recently been tremendous growth in the use of ultrasound for these interventions. -

Uroradiology Tutorial for Medical Students Lesson 3: Cystography & Urethrography – Part 1

Uroradiology Tutorial For Medical Students Lesson 3: Cystography & Urethrography – Part 1 American Urological Association Introduction • Conventional radiography of the urinary tract includes several diagnostic studies: – Cystogram – Retrograde urethrogram – Voiding cystourethrogram • All of these studies answer questions that are essential to urologic patient management Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG) • The voiding cystourethrogram is a dynamic test used to define the anatomy and, in part, the function of the lower urinary tract. It is performed by placing a catheter through the urethra into the bladder, filling the bladder with contrast material and then taking x-rays while the patient voids. You can imagine how popular it is among children. Scout Film • Several films are taken when performing a VCUG. The first image is a KUB called the scout film. On this film one can evaluate the bones of the spine and pelvis (injury or congenital anomaly such as spina bifida) and the soft tissues (calcifications, foreign bodies, etc.). • Normal scout image • What gender? Scout Film • Patients with urologic problems (urine infection or incontinence) may have a spinal abnormality that results in abnormal innervation of the bladder. Such anomalies are commonly associated with anomalies of the vertebral column. Let’s look at some spines. • Here is a spine from a normal KUB or scout film. Notice that the posterior processes of all the vertebrae are intact. You can see the posterior process behind and below each vertebral body. • Here is another scout film. Notice that the posterior processes are absent below L-4. This patient has lower lumbar spina bifida. Read This Scout Film • The bones are normal • What about soft tissues (bowel, etc.)? • This child has significant constipation. -

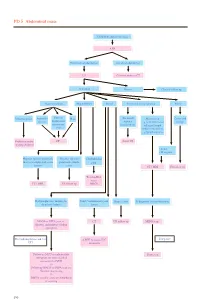

PD 5 Abdominal Mass

PD 5 Abdominal mass Child with abdominal mass AXR No intestinal obstruction Intestinal obstruction US Contrast study or CT Abnormal Normal Clinical follow up Gastrointestinal Hepatobiliary Renal Non-renal retroperitoneal Pelvic Intussusception Appendix Enteric/ Mass (Neonatal) Mass lesion Cystic and abscess duplication/ Adrenal e.g. neuroblastoma/ benign mesenteric haemorrhage enlarged lymph cyst node/ cystic lesion e.g.lymphangioma Reduction under CT Serial US imaging guidance • Solid • Malignant Hepatic/ splenic/ pancreatic Hepatic/ splenic/ Choledochal mass or complicated cystic pancreatic simple cyst lesions cysts CT / MRI US follow up Tc-99m-IDA scan / CT / MRI US follow up MRCP Hydronephrosis / multicystic Solid / complicated cystic Simple cysts If diagnosis is neuroblastoma dysplastic kidney lesion MAG3 or DTPA scan +/- CT US follow up MIBG scan diuretic and indirect voiding cystogram If negative For hydronephrosis and / or ± MRI to assess IVC UTI extension Follow up MCU or radionuclide Bone scan cystogram for more detailed assessment of VUR +/- Follow up MAG3 or DTPA scan for function monitoring +/- DMSA scan for acute pyelonephritis or scarring 190 PD 5 Abdominal mass REMARKS 1 Plain radiograph 1.1 Plain abdominal X-ray (AXR) is useful to exclude intestinal obstruction in children with constipation or abdominal distension, to locate mass, to detect any calcification, and to look for any skeletal involvement. 2 US 2.1 US helps to determine the organ of origin, to define the mass, to look for any metastases and to assess the vascularity of the mass with colour Doppler. A likely diagnosis can usually be made. 3 Nuclear medicine 3.1 Technetium 99m - Mercaptoacetyltriglycine (Tc-99m-MAG3) is the preferred radiotracer for renal scan.1 3.2 Tc-99m-MAG3 renography is able to provide information on renal position, perfusion, differential function and transit times. -

FDA-Approved Radiopharmaceuticals

Medication Management FDA-approved radiopharmaceuticals This is a current list of all FDA-approved radiopharmaceuticals. USP <825> requires the use of conventionally manufactured drug products (e.g., NDA, ANDA) for Immediate Use. Nuclear medicine practitioners that receive radiopharmaceuticals that originate from sources other than the manufacturers listed in these tables may be using unapproved copies. Radiopharmaceutical Manufacturer Trade names Approved indications in adults (Pediatric use as noted) 1 Carbon-11 choline Various - Indicated for PET imaging of patients with suspected prostate cancer recurrence based upon elevated blood prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels following initial therapy and non-informative bone scintigraphy, computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to help identify potential sites of prostate cancer recurrence for subsequent histologic confirmation 2 Carbon-14 urea Halyard Health PYtest Detection of gastric urease as an aid in the diagnosis of H.pylori infection in the stomach 3 Copper-64 dotatate Curium Detectnet™ Indicated for use with positron emission tomography (PET) for localization of somatostatin receptor positive neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in adult patients 4 Fluorine-18 florbetaben Life Molecular Neuraceq™ Indicated for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging of the brain to Imaging estimate β amyloid neuritic plaque density in adult patients with cognitive impairment who are being evaluated for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or other causes of cognitive decline 5 Fluorine-18 -

DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month

“DOCENDO DECIMUS” VOL 5 NO 5 May 2018 DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month These cases have been removed of identifying information. These cases are intended for peer review and educational purposes only. Welcome to the DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month! In conjunction with our Pediatric Radiology specialists from ARA, we hope you enjoy these monthly radiological highlights from the case files of the Emergency Department at DCMC. These cases are meant to highlight important chief complaints, cases, and radiology findings that we all encounter every day. Conference Schedule: May 2018 If you enjoy these reviews, we invite you to 2nd - 9: 00 Peds Neuroimaging……Dr Munns, Vezzetti, Leake check out Pediatric Emergency Medicine 10:00 Head Injuries……………….Drs Singh and Kienstra Fellowship Radiology rounds, which are offered 11:00 QI: ED Throughput………….Drs Harrison and Iyer quarterly and are held with the outstanding 9th - 8:00 Bioterrorism………..………Drs Munns and Remick 9:00 Diaster Simulation……………..…Simulation Faculty support of the Pediatric Radiology specialists at Austin Radiologic Association. 16th - 9:00 Environmental Toxins…..…….Drs Fusco and Earp 10:00 Wheezing Beyond Asthma………….……..Dr Allen 11:00 TBD If you have and questions or feedback regarding 12:00 ED Staff Meeting the Case of the Month format, feel free to 23rd - 9:00 Assessing/Enhancing Causality..……Dr Wilkinson 10:00 TBD email Robert Vezzetti, MD at 11:00 TBD [email protected]. 30th - 9:00 M&M……………………..…….Drs Schunk and Gorn 10:00 Board Review: Cardiology………………Dr Ruttan 12:00 Research Update……………….…….Dr Wilkinson This Month: Urinary tract infections are Guest Radiologist: Dr David Leake, MD common in children and generally nothing unusual. -

Radionuclide Cystography 138

The American College of Radiology, with more than 30,000 members, is the principal organization of radiologists, radiation oncologists, and clinical medical physicists in the United States. The College is a nonprofit professional society whose primary purposes are to advance the science of radiology, improve radiologic services to the patient, study the socioeconomic aspects of the practice of radiology, and encourage continuing education for radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and persons practicing in allied professional fields. The American College of Radiology will periodically define new practice guidelines and technical standards for radiologic practice to help advance the science of radiology and to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the United States. Existing practice guidelines and technical standards will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated. Each practice guideline and technical standard, representing a policy statement by the College, has undergone a thorough consensus process in which it has been subjected to extensive review, requiring the approval of the Commission on Quality and Safety as well as the ACR Board of Chancellors, the ACR Council Steering Committee, and the ACR Council. The practice guidelines and technical standards recognize that the safe and effective use of diagnostic and therapeutic radiology requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in each document. Reproduction or modification of the published practice guideline and technical standard by those entities not providing these services is not authorized. Revised 2010 (Res. 25)* ACR–SPR–SNM PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF ADULT AND PEDIATRIC RADIONUCLIDE CYSTOGRAPHY PREAMBLE These guidelines are an educational tool designed to assist Therefore, it should be recognized that adherence to these practitioners in providing appropriate radiologic care for guidelines will not assure an accurate diagnosis or a patients.