DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contrast‐Enhanced Ultrasound Bibliography General Principles 1

Contrast‐enhanced Ultrasound Bibliography General Principles 1.Claudon M et al. Guidlines and Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Contrast Ultrasound (CEUS)‐Update 2008 Ultraschall in Med 2008;29:28‐44 2.Cosgrove. D. Editorial. Eur Radiol Suppl (2004).14[Suppl 8]:1‐3 3.Burns PN, Wilson,S. Microbubble Contrast for Radiological Imaging:1 Principles. Ultrasound Quarterly 2006;22:5‐11 4.Wilson S et al. Contrast‐enhanced Ultrasound: What is the Evidence and What Are the Obstacles? AJR. 2009;193:55‐60 Safety 1.ter Haar GR. Ultrasonic Contrast Agents: Safety Considerations Reviewed. Eur J Radiol 2002;41:217‐221 2. Main MI. Ultrasound Contrast Agent Safety. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2009:2:1057‐ 1059 3. Pisaglia F et al. SonoVue in Abdominal applications: Retrospective Analysis of 23188 Investigations. Ultrasound in Med and Biol.2006;32:1369‐1375 4. Hynynen K et al. The Threshold for Brain Damage in Rabbits Induced By Bursts of Ultrasound in the Presence of an Ultrasound Contrast Agent (Optison). Ultrasound in Med and Biol;29:473‐481 Voiding Urosonography 1.Darge K. et al. Reflux in Young Patients: Comparison of Voiding US of the Bladder and Retrovesical Space with Echo Enhancement versus Voiding Cystourethrography for Diagnosis. Radiology 1999;210:201‐207 2.Radmayr C et al. Contrast Enhanced Reflux Sonography in Children: A Comparison to Standard Radiological Imaging J Urol 2002;167:1428‐30 Liver Lesion Characterization 1.Bolondi L et al. New Perspectives for the Use of Contrast‐Enhanced Liver Ultrasound in Clinical Practice. Digestive and Liver Disease 2007;39:187‐195 2.Berry J, Sidu, P. -

Urological Trauma

Guidelines on Urological Trauma D. Lynch, L. Martinez-Piñeiro, E. Plas, E. Serafetinidis, L. Turkeri, R. Santucci, M. Hohenfellner © European Association of Urology 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. RENAL TRAUMA 5 1.1 Background 5 1.2 Mode of injury 5 1.2.1 Injury classification 5 1.3 Diagnosis: initial emergency assessment 6 1.3.1 History and physical examination 6 1.3.1.1 Guidelines on history and physical examination 7 1.3.2 Laboratory evaluation 7 1.3.2.1 Guidelines on laboratory evaluation 7 1.3.3 Imaging: criteria for radiographic assessment in adults 7 1.3.3.1 Ultrasonography 7 1.3.3.2 Standard intravenous pyelography (IVP) 8 1.3.3.3 One shot intraoperative intravenous pyelography (IVP) 8 1.3.3.4 Computed tomography (CT) 8 1.3.3.5 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 9 1.3.3.6 Angiography 9 1.3.3.7 Radionuclide scans 9 1.3.3.8 Guidelines on radiographic assessment 9 1.4 Treatment 10 1.4.1 Indications for renal exploration 10 1.4.2 Operative findings and reconstruction 10 1.4.3 Non-operative management of renal injuries 11 1.4.4 Guidelines on management of renal trauma 11 1.4.5 Post-operative care and follow-up 11 1.4.5.1 Guidelines on post-operative management and follow-up 12 1.4.6 Complications 12 1.4.6.1 Guidelines on management of complications 12 1.4.7 Paediatric renal trauma 12 1.4.7.1 Guidelines on management of paediatric trauma 13 1.4.8 Renal injury in the polytrauma patient 13 1.4.8.1 Guidelines on management of polytrauma with associated renal injury 14 1.5 Suggestions for future research studies 14 1.6 Algorithms 14 1.7 References 17 2. -

Renal Ultrasonography

The American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology Application for Certification Renal Ultrasonography Revised 10/5/10 The American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology Application for Certification Renal Ultrasonography This application packet is composed of several parts: • Requirements for certification • Form for documentation of completion of basic requirements • Application form Checklist (check all that are included with application) Completed application form Documentation of didactic training Documentation of supervised studies Documentation of completion of basic requirements form Set of studies with follow-up Set of sample studies (Please label cases to reflect IB(3) or IIC of the application. Peer reference letter Application fee ($500/members or $750/non-members effective 1/1/08) *Non-member fee includes ASDIN membership for remainder of membership year from date of certification application. Basis for certification (check one) Nephrology fellowship based training program CME - accredited training program Other Certification requested (check one) General certification in renal ultrasonography Certification in renal transplantation ultrasonography Two copies of the application and all documentation should be submitted to the ASDIN office. Copies should be one of the following: a) two paper copies, OR b) one paper copy and one cd rom copy, OR c) one paper copy and one copy sent electronically to [email protected] Mail all application materials to: The American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology Attn: Bertinna Dubra 134 Fairmont Street, Suite B Clinton, MS 39056 Revised 10/5/10 2 American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology Requirements for Certification in Renal Ultrasonography I. Certification of nephrologists to perform and interpret sonograms of the kidney and bladder. -

Renal Relevant Radiology: Use of Ultrasonography in Patients with AKI

Renal Relevant Radiology: Use of Ultrasonography in Patients with AKI Sarah Faubel,* Nayana U. Patel,† Mark E. Lockhart,‡ and Melissa A. Cadnapaphornchai§ Summary As judged by the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria, renal Doppler ultrasonography is the most appropriate imaging test in the evaluation of AKI and has the highest level of recommendation. Unfortunately, nephrologists are rarely specifically trained in ultrasonography technique and interpretation, and *Division of Internal Medicine, Nephrology, important clinical information obtained from renal ultrasonography may not be appreciated. In this review, the University of Colorado strengths and limitations of grayscale ultrasonography in the evaluation of patients with AKI will be discussed and Denver Veterans with attention to its use for (1) assessment of intrinsic causes of AKI, (2) distinguishing acute from chronic kidney Affairs Medical Center, 3 Denver, Colorado; diseases, and ( ) detection of obstruction. The use of Doppler imaging and the resistive index in patients with † AKI will be reviewed with attention to its use for (1) predicting the development of AKI, (2) predicting the Department of 3 Radiology and prognosis of AKI, and ( ) distinguishing prerenal azotemia from intrinsic AKI. Finally, pediatric considerations in §Department of Internal the use of ultrasonography in AKI will be reviewed. Medicine and Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 382–394, 2014. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04840513 Pediatrics, Nephrology, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado; and Introduction structures on ultrasonography images. The renal cap- ‡Department of Renal ultrasonography is typically the most appro- sule consists of thin fibrous tissue, which is next to Radiology, University of priate and useful radiologic test in the evaluation of fat, and thus the kidney often appears to be surroun- Alabama at Birmingham, patients with AKI (1). -

ACR–SPR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Voiding

The American College of Radiology, with more than 30,000 members, is the principal organization of radiologists, radiation oncologists, and clinical medical physicists in the United States. The College is a nonprofit professional society whose primary purposes are to advance the science of radiology, improve radiologic services to the patient, study the socioeconomic aspects of the practice of radiology, and encourage continuing education for radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and persons practicing in allied professional fields. The American College of Radiology will periodically define new practice parameters and technical standards for radiologic practice to help advance the science of radiology and to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the United States. Existing practice parameters and technical standards will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated. Each practice parameter and technical standard, representing a policy statement by the College, has undergone a thorough consensus process in which it has been subjected to extensive review and approval. The practice parameters and technical standards recognize that the safe and effective use of diagnostic and therapeutic radiology requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in each document. Reproduction or modification of the published practice parameter and technical standard by those entities not providing these services is not authorized. Revised 2019 (Resolution 10)* ACR–SPR PRACTICE PARAMETER FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF FLUOROSCOPIC AND SONOGRAPHIC VOIDING CYSTOURETHROGRAPHY IN CHILDREN PREAMBLE This document is an educational tool designed to assist practitioners in providing appropriate radiologic care for patients. Practice Parameters and Technical Standards are not inflexible rules or requirements of practice and are not intended, nor should they be used, to establish a legal standard of care1. -

500 Pyelograms Done After Angiocardiography. the Urinary Tract

9 Section ofRadiology 419 often transitory, it can readily be reproduced by In 200 consecutive pyelograms, analysed both instructing the child to hold back urine and we by congenital heart lesion and urinary tract now believe that this is a common variation of the abnormality, the incidence of abnormal pyelo- normal. It is probably due to distension of the grams was 13 %. The range ofabnormality in both thin-walled proximal urethra, the less distensible is very wide. Pyelogram abnormalities in this bladder neck and distal urethra forming two series and subsequently have included failure of relatively narrow segments. maturation of kidney with pelvis lying intra- renally, solitary kidney, chronic pyelonephritic A 'corkscrew urethra' has been seen in 4 boys kidney, large kidneys, renal rotation, hydro- in this series. It may be associated with reflux. nephrosis, absence of renal pelves, duplication of Cystoscopy and urethroscopy has been normal kidney and ureter (one having a pyelonephritic and in one patient recordings of pressure and lower segment and evidence of vesicoureteric flow were also normal. We can only assume that reflux - Williams 1962), hydroureter and spinal this appearance is produced by redundant folds defects with neurogenic bladder. Factors affecting of mucosa; certainly there has been no evidence cardiac development may affect organogenesis in of obstruction in any of our cases. the urinary tract. The rubella virus was the defined factor in a patient, aged 4 months, with patent Summary ductus arteriosus, pulmonary hypertension and Micturating cystograms carried out in 232 pneumonitis and a miniature left kidney (autopsy children presenting with urinary infection, but proof). -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

Technical Report—Diagnosis and Management of an Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Young Children

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS Technical Report—Diagnosis and Management of an Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Young Children S. Maria E. Finnell, MD, MS, Aaron E. Carroll, MD, MS, Stephen M. Downs, MD, MS, and the Subcommittee on abstract Urinary Tract Infection OBJECTIVES: The diagnosis and management of urinary tract infec- KEY WORDS tions (UTIs) in young children are clinically challenging. This report was urinary tract infection, infants, children, vesicoureteral reflux, voiding cystourethrography, antimicrobial, prophylaxis, developed to inform the revised, evidence-based, clinical guideline re- antibiotic prophylaxis, pyelonephritis garding the diagnosis and management of initial UTIs in febrile infants ABBREVIATIONS and young children, 2 to 24 months of age, from the American Academy UTI—urinary tract infection of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection. VUR—vesicoureteral reflux VCUG—voiding cystourethrography METHODS: The conceptual model presented in the 1999 technical re- CI—confidence interval port was updated after a comprehensive review of published litera- RR—risk ratio ture. Studies with potentially new information or with evidence that RCT—randomized controlled trial LR—likelihood ratio reinforced the 1999 technical report were retained. Meta-analyses on SPA—suprapubic aspiration the effectiveness of antimicrobial prophylaxis to prevent recurrent UTI This document is copyrighted and is property of the American were performed. Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American RESULTS: Review of recent literature revealed new evidence in the Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through following areas. Certain clinical findings and new urinalysis methods a process approved by the Board of Directors. -

Use of Ultrasound As an Alternative to Fluoroscopy

Use of Ultrasound as an Alternative to Fluoroscopy Rahul Sheth, MD Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA PART 1. INTERVENTIONAL PROCEDURES Fluoroscopy has significantly contributed to the advent and proliferation of image-guided interventions across the gamut of clinical medicine. While these procedures allow for the execution of often complex internal manipulations through a small skin nick rather than a surgical incision, they are not without risk, including the risks of ionizing radiation [1]. In these procedures, fluoroscopy simply serves as an image guidance tool, and as such, alternative imaging modalities that do not rely on ionizing radiation can and should be considered. For example, as a real-time, high resolution imaging modality, ultrasound shares many characteristics with fluoroscopy. However, due to its lack of reliance on ionizing radiation, ultrasound is often the imaging tool of choice for a number of image-guided interventions for which fluoroscopy may also be considered, particularly in the pediatric population. The following examples illustrate specific indications in which ultrasound is preferred over fluoroscopy for interventional procedures. Ultrasound Instead Of Fluoroscopy For Musculoskeletal Procedures Ultrasound is ideally suited for image guided interventions upon the musculoskeletal system [2], as the depth of penetration required for these procedures is typically within several centimeters. A wide array of musculoskeletal interventions can be performed with ultrasound guidance, including arthrocentesis [3,4], joint and soft tissue steroid/anesthetic injections [5,6,7], and aspirations [8,9]. Moreover, while fluoroscopy is the most common imaging modality used for cervical nerve blocks and facet injections, there has recently been tremendous growth in the use of ultrasound for these interventions. -

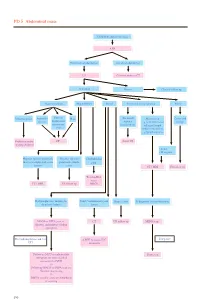

PD 5 Abdominal Mass

PD 5 Abdominal mass Child with abdominal mass AXR No intestinal obstruction Intestinal obstruction US Contrast study or CT Abnormal Normal Clinical follow up Gastrointestinal Hepatobiliary Renal Non-renal retroperitoneal Pelvic Intussusception Appendix Enteric/ Mass (Neonatal) Mass lesion Cystic and abscess duplication/ Adrenal e.g. neuroblastoma/ benign mesenteric haemorrhage enlarged lymph cyst node/ cystic lesion e.g.lymphangioma Reduction under CT Serial US imaging guidance • Solid • Malignant Hepatic/ splenic/ pancreatic Hepatic/ splenic/ Choledochal mass or complicated cystic pancreatic simple cyst lesions cysts CT / MRI US follow up Tc-99m-IDA scan / CT / MRI US follow up MRCP Hydronephrosis / multicystic Solid / complicated cystic Simple cysts If diagnosis is neuroblastoma dysplastic kidney lesion MAG3 or DTPA scan +/- CT US follow up MIBG scan diuretic and indirect voiding cystogram If negative For hydronephrosis and / or ± MRI to assess IVC UTI extension Follow up MCU or radionuclide Bone scan cystogram for more detailed assessment of VUR +/- Follow up MAG3 or DTPA scan for function monitoring +/- DMSA scan for acute pyelonephritis or scarring 190 PD 5 Abdominal mass REMARKS 1 Plain radiograph 1.1 Plain abdominal X-ray (AXR) is useful to exclude intestinal obstruction in children with constipation or abdominal distension, to locate mass, to detect any calcification, and to look for any skeletal involvement. 2 US 2.1 US helps to determine the organ of origin, to define the mass, to look for any metastases and to assess the vascularity of the mass with colour Doppler. A likely diagnosis can usually be made. 3 Nuclear medicine 3.1 Technetium 99m - Mercaptoacetyltriglycine (Tc-99m-MAG3) is the preferred radiotracer for renal scan.1 3.2 Tc-99m-MAG3 renography is able to provide information on renal position, perfusion, differential function and transit times. -

Successful Cutting Balloon Angioplasty in a Child with Resistant Renal Artery Stenosis Jae Sung Son*

Son BMC Res Notes (2015) 8:670 DOI 10.1186/s13104-015-1673-z CASE REPORT Open Access Successful cutting balloon angioplasty in a child with resistant renal artery stenosis Jae Sung Son* Abstract Background: Although renovascular hypertension is a rare disease, it is associated with 5–10 % of cases of childhood hypertension. It is a potentially treatable cause of hypertension, and is often caused by renal artery stenosis (RAS). The most common cause of RAS in children is fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD). The options for treating RAS depend on the location, severity and abnormality underlying the condition. Case presentation: A previously healthy 7-year-old Korean boy presented to our clinic with hypertension and headache. Renal ultrasonography and multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) showed severe focal stenosis at the middle portion of the left renal artery (LRA) and multiple collateral vessels. Percutaneous balloon angioplasty was performed as an initial treatment, but yielded unsatisfactory results. The presence of intimal-type FMD was suspected based on his clinical features, angiographic appearance, and resistance to percutaneous transluminal renal angio- plasty. Thereafter, his blood pressure was normalized using antihypertensive medication. Follow-up multi-detector computed tomography at 11 years of age showed persistent severe stenosis of the LRA. After unsuccessful attempts to perform balloon angioplasty, 3.5-mm cutting balloon angioplasty (CBA) was performed and yielded satisfactory results. He was discharged without any medication. At 1 year and 6 months after the intervention, he has been nor- motensive and had not required any antihypertensive medication. Conclusion: The author describes a case of resistant RAS that was detected on MDCT and successfully treated using percutaneous (CBA). -

Kidney, Ureter, Bladder) Compared to Non-Contrast CT (Computed Tomography) in Patients of Ureteric Calculi

Jebmh.com Original Research Article Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound and Plain X-Ray KUB (Kidney, Ureter, Bladder) Compared to Non-Contrast CT (Computed Tomography) in Patients of Ureteric Calculi N. Imdad Ali1, Noor Elahi Pasha2, Ravishankar T.H.S.3 1, 2, 3 Department of Urology, Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences, Bellary, Karnataka, India. ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Imaging plays a major role in the diagnosis and management of patients with Corresponding Author: urolithiasis. Non-Contrast Computed Tomography (NCCT) is generally accepted as Dr. Ravishankar T.H.S., the gold standard, but there are concerns over higher radiation exposure from Department of Urology, Vijayanagar Institute NCCT to the patient population. Our prospective study compared the diagnostic of Medical Sciences, accuracy of plain X-ray KUB (Kidney, Ureter, Bladder) and USG (Ultrasonography) Bellary, Karnataka, India. with NCCT in the evaluation of patients with ureteric colic. E-mail: [email protected] METHODS DOI: 10.18410/jebmh/2020/567 This study conducted from December 2018 to January 2020 in the Department of Urology, Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences, and attached Hospital. 230 How to Cite This Article: patients with ureteric colic were evaluated for ureteric calculi with x-ray KUB, USG Ali NI, Pasha NE, Ravishankar THS. (Ultrasonography) abdomen and pelvis and NCCT (Non-Contrast Computed Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound and plain X-ray KUB (kidney, ureter, bladder) Tomography) KUB region. compared to non-contrast CT (computed tomography) in patients of ureteric RESULTS calculi. J Evid Based Med Healthc 2020; Out of 230 patients, 168 (73 %) were males and 62 (26.9 %) were females. Ages 7(47), 2762-2766.